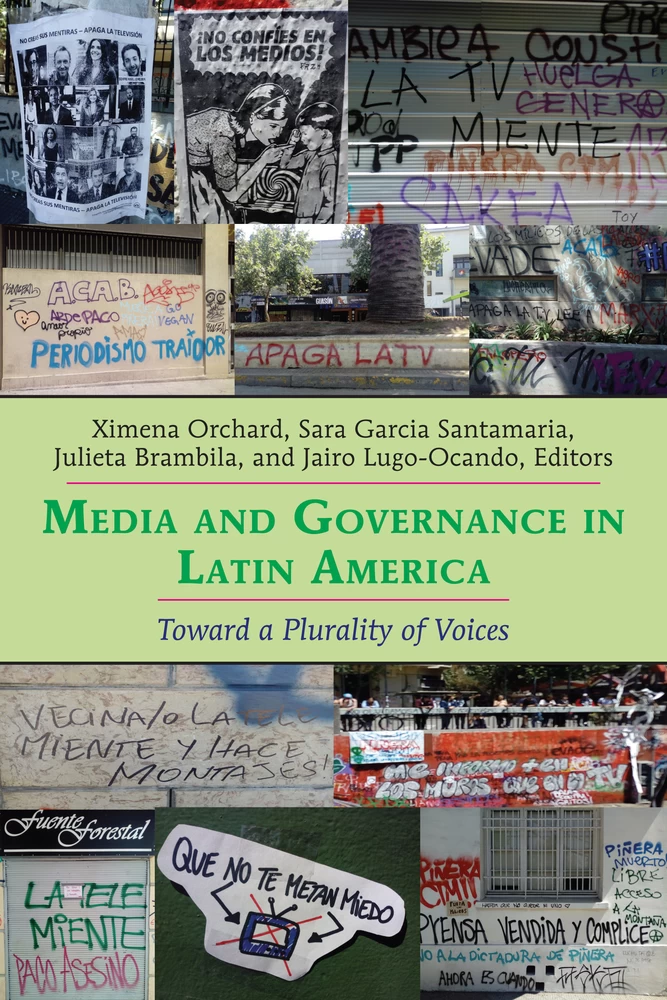

Media and Governance in Latin America

Toward a Plurality of Voices

Summary

The rise in recent years of authoritarianism, populism and nationalism, both in fragile and stable democratic systems, makes media pluralism an intellectual and empirical cornerstone of any debate about the future of democratic governance around the world. This book—useful for students and researchers on topics such as Media, Communications, Latin American Studies and Politics—aims to make a contribution to such debate by approaching some pressing questions about the relationship of Latin American governments with media structures, journalistic practices, the communication capabilities of vulnerable populations and the expressive opportunities of the general public.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the Book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction: Why Media Pluralism Matters for Democratic Governance

- PART 1:Theoretical Debates and Production of Knowledge About Media and Communication in Latin America

- Chapter 2 Beyond Pluralism: Communication Rights and Civil Society in Latin America

- Chapter 3 Toward a Journalism-Other as a Paradigm of Latin American Journalistic Cultures Within the Framework of the Decolonial Turn

- Chapter 4 How to Incorporate Latin American Communication Studies into Northern/Western Circles? Reflections on Academic Pluralism as Co-Production

- PART 2:Media, Politics, and Democracy

- Chapter 5 Democracy as Corruption: The News Media and the Debunking of Democracy in Brazil

- Chapter 6 Media in Authoritarian Contexts: A Logics Approach to Journalistic Professional Resistance in Cuba and Venezuela

- Chapter 7 The Elite Echo-Chamber: Media Visibility as an Intra-Elite Political Resource

- Chapter 8 A Trajectory of Caudillo Press, Journalism, and the Authoritarian Dilemma in Venezuela

- PART 3:Technology, Voice, and Participation

- Chapter 9 Commenting on Disaster: News Comments as a Representation of the Public’s Voice

- Chapter 10 Indigenous Media in Argentina: Beyond Media Pluralism, Toward Media Diversity, Through ‘Communication with Identity’

- Chapter 11 Counter-Hegemonic Media Production from Urban and Rural Margins in Brazil

- Chapter 12 Young Chileans’ Voices: The Fabric of Their Listening Practices While Consuming News

- Chapter 13 Conclusion: New Maquilas for Old Powers? The (Un)Changing Face of Latin America’s Media in the Post-Pink-Tide Era

- Epilogue: Why the Digital Revolution Hasn’t Made Media Pluralism Irrelevant: Communication Abundance and Concentration

- List of Contributors

1. Introduction: Why Media Pluralism Matters for Democratic Governance

Lecturer and researcher, Universidad Alberto Hurtado. Email: morchard@uahurtado.cl

Assistant Professor at Blanquerna, Universitat Ramon Llull. Email: sarags1@blanquerna.url.edu

A buzzword in media and communications studies, pluralism is a standard against which the state of freedom of expression and the press are commonly evaluated, together with the overall performance of media systems and the quality of democracies. Democratic theory recognizes media pluralism as a relevant variable to assess democracy (Dahl, 1998), and for that reason we understand media pluralism as a normative horizon toward which civil life, state regulatory efforts and press regulations are oriented in any democratic society. Questions about media pluralism—broadly understood as the striving for diverse and inclusive media spheres—are an essential part of scholarly debates on media and democratization, a debate made more complex as a result of the legitimacy crisis that has impacted upon legacy media, the opaque modes of governance of social media platforms and the myriad ways in which citizens make use of communication technologies. While such questions have been approached from different theoretical perspectives, they are fundamentally connected to the way in which democracy is understood, the way in which social and political differences are mediated and the degree to which the media has the necessary agency for challenging the political and economic status quo.

Two decades into the 21st century, Latin American media landscapes are far from resembling the liberal ideas of a plural, free press. The Latin American experience has challenged long-held assumptions of a correlation ←1 | 2→between democratization and media pluralism. On the one hand, both political and media democratization do not seem to progress in a linear way and authoritarian backlashes are common in new and transitional democracies in the region (Guerrero & Márquez Ramírez 2014; Lugo-Ocando & Garcia Santamaria 2015; Segura & Waisbord 2016), and also beyond (Voltmer & Kraetzschmar 2015; Zielonka, 2015). On the other hand, media pluralism has been at the center of political disputes with different levels of intensity in Latin American countries. We see the construction of pluralistic spheres as a process in which communicational practices between individuals, organizations and institutions are co-dependent on larger social and political processes. In the 21st century, both government and media landscapes have become more complex and unpredictable. In the midst of a crisis of traditional institutions, the multiplication of communication channels has been conducive toward all forms of information overload. It would be easy to argue that more media outlets and distribution channels, together with larger amounts of content, should result in a more pluralistic public debate. Yet pluralism is not necessarily a matter of quantity but equality in the ability to render issues visible in the public debate, the possibility of having a voice in such public spaces and of that voice being heard. Pluralism and communication capabilities are therefore closely intertwined, and as long as communication capabilities among social and political actors are unequally distributed, those power imbalances will be reflected in the media.

Questions about media plurality have a long history in Latin American communication scholarship, and this is not happenstance but the result of both the direct experience of global imbalances in communication matters, together with the persistence of local and national disputes over communication policies and the structure of media industries. Latin American scholars were central in the writing of the UNESCO’s MacBride Report (1980), an international milestone that underlined the consequences of communication disparities, and the dangers of the commodification of information. Nearly forty years after its publication, this report remains more declarative than anything else (Beltrán, 2006; Pasquali, 2005), and new media platforms are mostly organized by the same market logics as those of legacy media, far from the “information order” envisioned by the authors of the report (Fuchs, 2015).

In this chapter, we will start by identifying the main dimensions in the discussion about media pluralism and how it relates to processes of democratization. Afterwards, we will turn our attention to the identification of relevant strands of research that tackle the relationship between media pluralism and democracy in the region, particularly around market structures and ←2 | 3→media policies on the one hand, and dynamics of social inclusion and communication inequalities, on the other. Although interlinked, these strands of research shed light on complementary questions about why pluralism matters for democratic governance. Finally, the structure of the book will be introduced in order to locate the contributions of the authors within this literature.

In the series of conferences that precede this book, as well as in the title of this chapter, we have privileged the term “governance” and we believe some clarification is needed. We use governance mainly to signal that it is our belief that in order to critically assess how media and communications interact with social and political change it is important to go beyond traditional political institutions such as the presidency, congress or political parties, and to incorporate other groups—bureaucracies, corporate actors, civil society organizations—that interact with each other through the media and are regularly represented and self-represented in different media platforms. We acknowledge that “governance”, and in particular “good governance”, is a loaded term in the region because it has become a rhetorical device frequently used by international organizations such as the World Bank or the OECD to assess the performance of Latin American democracies. We are not necessarily associating the term “governance” with such normative expectations about states’ behavior but expanding the potential locus for enquiry at the time of problematizing the relationship between media pluralism and democracy.

Conventionally, the concept of governance refers to the process through which different actors within a given society decide their goals, modes of action and sense of direction (Aguilar, 2006). Definitions of governance emphasize, therefore, the ability of citizens to participate in decision-making processes and to hold states accountable for their actions (Cohen, Lupu, & Zechmeister, 2017). As such, the use of the concept of good governance presumes an important degree of social autonomy in the intermediate bodies of society, in addition to respect for human rights, low levels of corruption and adequate mechanisms for public and private accountability. How are processes of governance, then, connected to media and communications? Our main contention is that the ability of social and political actors to participate in public debate, become visible and get fair social recognition is usually defined in different media platforms and heavily mediated by their communication capabilities, yet communication policies and practices are not always problematized together with democratic governance, especially outside communication scholarship. We attempt such endeavor taking Latin America as a locus for academic enquiry, a region that concentrates high levels of inequality, ←3 | 4→which is particularly relevant when we think about actors’ capacities to render social problems visible and to intervene in public decision-making.

Media Pluralism and Democratic Expectations

The aspiration to pluralism in the media is frequently linked to that of democratization, yet the concept of media pluralism has been built around different and sometimes conflicting narratives. For this reason, instead of taking for granted the normative value of media pluralism for democracy it is important to make some qualifications.

Broadly speaking, the concept of media pluralism refers to the extent to which the media contributes toward the existence and safeguarding of a pluralistic public discourse. There is not a single monolithic approach to media pluralism, neither theoretically or empirically; yet it is primarily concerned with mechanisms through which differences in society are mediated; how diverse mediated representations are, and how feasible is the circulation of pluralistic discourses, which connects with matters of inclusion and exclusion, as well as the possibility of contesting hegemonic discourses in the public debate (Raeijmaekers & Maeseele, 2015).

Empirically, concerns about media pluralism have been often discussed in connection to the organization of media markets, media policies and media contents, and the consequences of these to a plural circulation of ideas. Within the liberal tradition, these values are safeguarded by civil rights such as free speech and free press, which are deemed to be protected from the action of the state. In other words, by securing minimal state intervention in the organization of media markets it is believed that diversity will be protected. This line of thinking has been prevalent in Latin America, and it was instrumental in the liberalization of media markets under authoritarian governments, especially through the 70s and 80s of the last century; a process that resulted in the configuration of market-oriented media systems throughout the region. For the most part, the economic liberalization of media markets in Latin American countries, then, preceded the consolidation of democratic political institutions. Later on, while democratically elected governments replaced military juntas across the continent, these much-expected processes of political democratization proved not to be necessarily aligned to a greater capacity of the media to make power accountable, which—as discussed by Voltmer (2013)—has been a case in point in other transitional democracies around the world. The thesis of the modernization of media markets in the region, based on the merits of open markets and minimal state intervention (Tironi & Sunkel, 1993), encountered at the turn of the century some powerful ←4 | 5→counter-narratives that highlighted how commercially oriented media in the region were usually co-opted by political and corporate powers to become, in practice, demobilizing agents (Bresnahan, 2003; McChesney, 1999).

Over the past decades of the 21st century, assessments on the capacity of the media to act as a democratizing force have been frequent. Most authors highlight the limitations encountered on the road toward media independence and plurality, and some key conflicting areas are often identified as problematic. Among others are the oligarchic nature of media ownership and the persistent trend toward media ownership concentration (Becerra & Mastrini, 2017; Hughes & Lawson, 2005; Mastrini & Becerra, 2006; Sunkel & Geoffroy, 2002); uneven adherence to journalistic standards, and the limitations and threats encountered by Latin American journalism to fulfil watchdog roles (Dinatale & Gallo, 2010; Hughes & Mellado, 2016; Mellado, Moreira, Lagos, & Hernandez, 2012; Waisbord, 2000); scarcity of civic-oriented media outlets and the under-representation of disadvantaged social groups, together with disputes, achievements and failures around media policy reforms, understood as regulatory mechanisms expected to address some of these persistent problems (Becerra & Wagner 2018; Segura & Waisbord 2016).

Because assessments on the relationship between media and democracy are multi-factorial and context-dependent, conclusions on these areas vary among countries. Jebril, Stetka, and Loveless (2013) note that although an independent and plural media is expected to contribute toward democratization and political accountability, there is little research exploring how the media fulfil this normatively ascribed role, and scarce evidence supporting these claims. Interestingly, they call for theory-building rather than theory-testing research on this matter, acknowledging that the application of universal models may turn out to be more limiting than enlightening. We could argue that country differences make more difficult the possibility of a shared assessment about the relationship between media and democracy in the region. However, that would be a simplistic and deceitful answer. Latin America is a complex and heterogeneous region that cannot be treated as a unity, yet there are shared historical, political and socio-economic aspects that make the enquiry plausible. The identification of common areas of concern has opened the space for common characterizations of the Latin American media, as represented by the captured-liberal model proposed by Guerrero & Márquez-Ramírez (2014), a framework for analysis that acknowledges clear patterns in the region, particularly the way in which media environments mostly dominated by commercial media organizations are characterized by capture, either by corporate interests or political groups.

←5 | 6→Assessments about the relationship between media pluralism and democracy in the region are difficult for two main reasons. Firstly, because this is in itself an over-arching question that has to be disaggregated and acknowledge political variance across the region in order to offer some meaningful answers. Secondly, because media pluralism—as much as democracy—are normative standards toward which societies can strive but never fully achieve. Normative absolutes are ever-moving targets, and that is not exclusive to Latin American countries nor a consequence of “late” development, but a result of persistent inequalities and ever-present power struggles that makes the metaphor of the road toward democratization and development somehow inaccurate. Discussing the basic tenets of democracy, Dahl (1999) poses that meeting the demands of a fully functioning democracy is an aspiration rather than a reality, and therefore the gap between ideal and real democracy is deemed to remain quite large in every society. How we observe and assess the relationship between media pluralism and democracy will be, therefore, largely dependent on citizens’ demands and expectations of the democratic process itself.

Discussions about media and democracy in the region tend to adopt normative undertones, which have been reinforced by the foundational narratives of the journalistic practice. However, what if this idea was based on a double fallacy, one that assumes a historical correlation between journalism and democracy and another that takes that nexus as a valid universal across time and regions. Barbie Zelizer (2013) argues that assuming a journalism/democracy nexus is not just a distortion of the historical association between these two notions but has in fact a negative impact on the expectations we have about journalism and its democratizing potential in the global south. This is particularly problematic, she argues, when we try to understand and shape the way in which journalism works in new and transitional democracies. By focusing on a western idea of liberal democracy, the scholar argues that we are blinded by an elitist way of looking at journalism that disregards historical and geographic specificities and is, therefore, exclusionary in nature. This results in normative expectations that overshadow the many ways in which journalism is practiced in context, and the way it interacts with different configurations of democratic rule. The democratizing role of journalism has been questioned by a range of scholars, particularly drawing from the inconsistencies of this association in non-western contexts (Jacubowicz, 2007; Waisbord, 2012; Zelizer, 2013; Vodak & Kraetzschmar, 2015). The logical question that arises is whether it makes sense to use western normative expectations about journalism and liberal democracy in post-authoritarian countries that are, in fact, historically and contextually different. From a critical standpoint, ←6 | 7→Albuquerque (2019) considers that Latin American countries have built their identities as peripheries of the West, using a democratization framework that takes the West as a normative referential point. This framework, he argues, proves usually inadequate to explain why media institutions that are supposed to support democratic processes do not always act as expected. In a similar light, Voltmer (2013) argues that the implementation of democracy around the world has resulted in a range of hybrid democratic practices that both challenge and exceed default liberal expectations.

How could we accurately account for this democratic deficit in the media sphere? Can journalism and a pluralistic media contribute to fostering good governance and, thus, contribute to establishing the bases for a healthy democratic culture? To what extent has this connection mostly emphasized a western expectation that imposes some priorities upon other journalistic and media contexts? To what extent the use of social media platforms compensates for the shortcomings of legacy media in order to foster the proliferation of actors and voices in the public debate? Without the intention of fully answering these questions, we next turn our attention to identify relevant strands of research about media pluralism in Latin America, which may shed light about how media pluralism has been empirically observed in the region and why it matters for democracy.

Media Pluralism and Why It Matters for Democratic Governance

In order to pin down some of the ideas that we have so far developed, in this section of the chapter, we aim to discuss how media pluralism has been observed in practice. That is, how research about media pluralism and democratic governance has recently been developed. In order to do so, we identify two main areas that have been used to assess media pluralism, and around which it is possible to organize recent work about media pluralism in Latin America. These are (1) market structures and media policy reform and (2) social inclusion and communication inequalities. Instead of being a comprehensive account of all the research developed in and about the region, we aim to identify key areas of research that amass important bodies of empirical development, and pose questions yet to be answered in the relationship between media pluralism and democratic governance.

Market Structures and Media Policy Reform

As was discussed before, Latin American engagement with communications regulatory frameworks started around the 60s and 70s of the last century, ←7 | 8→mostly as a form of reflection and defense from what was perceived as unbalanced flows of information dominated by the global north. From the 80s and onwards, and together with the authoritarian waves that reshaped media markets through neo-liberal policies, the levels of media ownership concentration have been a permanent concern, since they remain high in most of the region (Becerra & Mastrini, 2017; Mastrini & Becerra, 2006) and are thus a potential threat to media plurality and the free circulation of ideas. International organizations such as UNESCO have sustained a role as articulators in the discussion about setting standards to tackle “undue concentration” of media ownership, understood as “the idea that one individual, or a corporate body, exercises control over an important part of an overall media market” (Mendel, García-Castillejo & Gómez, 2017, pp. 10).

From the turn of this century, the focus of attention on media policy has shifted altogether with a renewed interest in this area. In a commercially oriented media environment, an important group of Latin American countries has recently developed policy discussions and enacted fundamental changes, mostly oriented toward the regulation of privately owned media organizations and the stimulation of alternative forms of media, such as citizen, indigenous or state-owned media platforms. These discussions have revolved around distinct notions of the values that states are to protect through media policy: whether media policy should be articulated around the idea of the protection of liberties (free press, free speech) or around a human rights framework (rights to communication), in which not only individual liberties are protected but also the values of inclusiveness and equal opportunities of communication.

Discussions about media policy reform have been highly polarized and attempts at reform—mostly coming from progressive governments—have been often resisted by media corporations and some sectors of the population. Segura and Waisbord (2016) have extensively documented how media policy reforms in the region were fueled by limited pluralism and elite-captured media policies, supported by years-long citizen-led initiatives that found windows of political opportunity in governments led by sympathetic political elites. Becerra and Wagner (2018), in turn, argue that media reforms in countries such as Ecuador, Argentina, Bolivia, Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia were foregrounded by populism and tensions between governments and media organizations, a crisis of representation and permissive regulations that promoted historical media concentration.

Although not homogeneous in their aims and forms of implementation, most reforms contemplated some form of disruption of media markets, whether through limiting media ownership or granting space to new, ←8 | 9→non-commercial actors. Also, they regulated government advertising in an attempt to limit the discretionary use of state-funds to capture media organizations and avoid critical reporting, a problem particularly acute in countries such as Mexico and Argentina (Organization of American States, 2012). And controversially, some policy reforms entered the space of media content, granting governments the right to censor content that is considered untruthful or unbalanced, notably in Venezuela and Ecuador (Salojärvi, 2016).

Beyond policy discussions, politicians’ verbal attacks against media outlets are present throughout the ideological spectrum, from Nicolas Maduro’s Venezuela to Jair Bolsonaro’s Brazil. Attacks not only take place in a discursive sphere, but they materialize in discretional support for sympathetic media and journalists, while critical ones are victims of economic pressures, lawsuits and defamation campaigns.

The question that arises is whether media policy reform in the region has created a regulation that favors democratization, significantly shifting power relations toward more horizontal, collective and people-centered ownership and decision-making processes. The relationship between formal policies and informal practices has left many suspicious of the degree to which media reform has been so far able to dismantle unequal power relations. Or, rather, reforms have simply reinstitutionalized political control by shifting the composition of traditional networks of political patronage. Lugo-Ocando and Garcia Santamaria (2015) concluded that the new Latin American left appealed to the need of media reform in order to overcome past imbalances while in practice consolidating their own media hegemony. After all, it would be naïve to think that well-established elites have been completely removed from the equation. Even when regulation addresses power imbalances, other elements of journalistic culture, polarization, political parallelism, corporate interests and flawed governance models tend to persist over time.

The discussion about pluralism and media policy in the region extends also to new media platforms. As discussed by Segura and Waisbord (2019), rights-based public policies in new media platforms are currently being pushed forward by data activists around agendas such as open access to public information and cultural goods, as well as the protection of civil rights on the Internet: the protection of personal data, rights to privacy, rights to be forgotten or the avoidance of unwanted forms of commodification, surveillance and data extractivism.

Both long-standing and new concerns about the protection of media pluralism in the region allow for the identification of important questions to be answered. To what extent have media policies fostered pluralization ←9 | 10→rather than shifting hegemonic control from private to governmental hands, or from one political and economic elite to another? How human rights are best protected in a changing communication environment?

Plurality of Voices and Communication Inequalities

Most of the discussion on media pluralism in the region has been built around the idea that the oligarchic organization of media markets and different forms of media capture by powerful actors conspire against both fair representation, visibility options and media access of vast sectors of society: vulnerable populations, dissident organizations, and ethnic and gender minority groups.

Details

- Pages

- VIII, 274

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433169243

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433169250

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433169267

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433169281

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15615

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (January)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. VIII, 274 pp., 2 b/w ill., 2 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG