From Exploitation Back to Empowerment

Black Male Holistic (Under)Development Through Sport and (Mis)Education

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

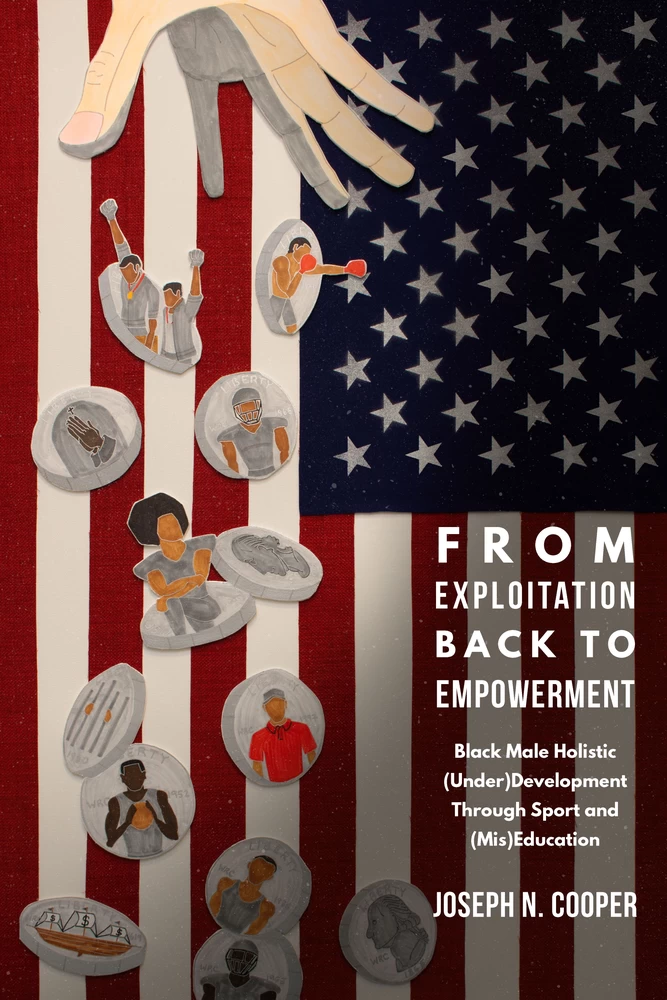

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Plight of Black Males in the United States: Conditions, Realities, and Complexities In and Through Sport and Beyond

- Foundation for Understanding Black Masculinities In and Through Sport and (Mis)Education

- My Positionality

- The Need for Critical Sociological and Ecological Examinations of Black Male Athletes

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 1. A Socio-Historical Overview of Black Males’ Sport Involvement in the United States

- Socio-Historical, Socio-Cultural, and Socio-Political Context for Understanding Black Males’ Sport Involvement

- The Era of Muscular Assimilationism In and Through Sport

- The Rise and Decline of Cultural Nationalism In and Through Sport

- Performative Black Masculinities In and Through Sport

- Ideological Hegemony and Mass Mediated Constructions of Black Masculinities In and Through Sport

- White Gazes with Phobic and Erotic Obsessions: Connections to Black Masculinities In and Through Sport

- Black Male Literal and Figurative Death In and Through Sport

- Chapter Summary

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 2. Systemic Miseducation Through Schooling and Sport

- Miseducation, Schooling, and Black Males

- Structural Intersectionality and Education Debt

- The Miseducation of Black Males Through Youth and Interscholastic Sport

- Black Male Early Socialization In and Through Sport

- The Conveyor Belt

- Athletic-Centric Prep and Private Schools

- The Miseducation of Black Males Through College Sport: Institutionalized Exploitation

- Athletic Role Engulfment and Identity Foreclosure

- Black Male Athletic Identity Foreclosure and Role Engulfment: A Theory of Gendered Racism In and Through Sport and Miseducation

- Junior Colleges (JUCOs)

- Special Admissions, Academic Underpreparedness, and Problematic Enrollment Trends

- Academic Clustering

- Gendered Racial Gaps with Academic Progress Rates and Graduation Success Rates

- The Myth of the Collegiate Model and “Student”- Athlete

- Chapter Summary

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 3. Towards a Framework for Black Male Holistic (Under)Development Through Sport and (Mis)Education

- Theoretical Issues and Pluralistic Counter-Approaches

- Critical Race Theory in Education and Sport

- Counter Storytelling, Counter Narratives, and Centrality of Experiential Knowledge

- Permanence of Racism

- Whiteness as Property Norm

- Interest Convergence

- Critique of Liberalism

- Intercentricity of Racism with Other Forms of Subordination

- Challenge to Dominant Ideology

- Commitment to Social Justice

- Transdisciplinary Perspective

- Community Cultural Wealth

- Strategic Responsiveness to Interest Convergence

- Anti-Deficit Achievement Framework and Progressive and Productive Black Masculinities

- Excellence Beyond Athletics Framework

- African American Male Theory

- Black Male Holistic (Under)Development Through Sport and (Mis)Education Theory and Socialization Models

- Chapter Summary

- Note

- References

- Chapter 4. Illusion of Singular Success Model: Holistic Underdevelopment and Athletic Identity Foreclosure Through Unconscious Exploitation

- The Interplay of Systemic Conditions for the Illusion of Singular Success Model and Black Male Athletes

- Socialization Phases of the Illusion of Singular Success Model

- Evidence of the Illusion of Singular Success Model

- Chapter Summary

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 5. Elite Athlete Lottery Model: Holistic (Under)Development and Interest Convergence with Exploitative Systems

- The Interplay of Systemic Conditions for the Elite Athletic Lottery Model and Black Male Athletes

- Socialization Phases of the Elite Athlete Lottery Model

- Evidence of the Elite Athlete Lottery Model

- Chapter Summary

- References

- Chapter 6. Transition Recovery Model: From Holistic Underdevelopment and Unconscious Exploitation to Holistic Development and Conscious Empowerment

- The Interplay of Systemic Conditions of the Transition Recovery Model and Black Male Athletes

- Socialization Phases of the Transition Recovery Model

- Evidence of the Transition Recovery Model

- Chapter Summary

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 7. Purposeful Participation for Expansive Personal Growth Model: Holistic Development Through Conscious Navigation of Exploitative Systems

- The Interplay of Systemic Conditions for the Purposeful Participation for Expansive Personal Growth Model and Black Male Athletes

- Socialization Phases for the Purposeful Participation for Expansive Personal Growth Model

- Evidence of the Purposeful Participation for Expansive Personal Growth Model

- Chapter Summary

- References

- Chapter 8. Holistic Empowerment Model: Conscious Resistance Against Exploitation

- The Interplay Between Systemic Conditions for the Holistic Empowerment Model and Black Male Athletes

- Socialization Phases of the Holistic Empowerment Model

- Evidence of the Holistic Empowerment Model

- Chapter Summary

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 9. Sustained Empowerment: The Unbreakable Legacy Continues

- Transformative Sustained Empowerment: A Blueprint for Positive Change Moving Forward

- Recommendations for Black Male Holistic Individuals, Families, and Communities

- Recommendations for Primary (Mis)Education Levels and Youth Sport Organizations

- Recommendations for Secondary (Mis)Education and Interscholastic Athletics

- Recommendations for Postsecondary (Mis)Education and Intercollegiate Sports

- Recommendations for Broader Society

- Chapter Summary

- Notes

- References

- Index

Figure 3.1: Black Male Holistic (Under)Development Through Sport and (Mis)Education Theory

Figure 4.1: Illusion of Singular Success Model (ISSM)

Figure 5.1: Elite Athlete Lottery Model (EALM)

Figure 6.1: Transition Recovery Model (TRM)

Figure 7.1: Purposeful Participation for Expansive Personal Growth Model (P2EPGM)

Figure 8.1: Holistic Empowerment Model (HEM)

It is a great privilege to write this foreword for Dr. Cooper. I vividly remember meeting him in Chapel Hill, NC, during his days as a graduate student. I was invited to sit on a panel during the College Sport Research Institute’s annual conference being held on the campus of UNC and Joe was in attendance. The panel was on some aspect of college sports and it consisted of myself, Jay Bilas, Danny Green, and Burke Mangus, who was then senior vice president, college sports programming for ESPN. The panel was lively as I challenged Jay Bilas and Burke Mangus to realize that the young Black males they covered on ESPN were actually people and not just robots. At lunch later that day, I had the opportunity to talk, debate, and engage with Joe. I knew then that he was the type of professor we needed to change the culture of big-time college sports. Quite frankly, I told him, we need professors who will engage Black student-athletes and who will encourage and challenge them to be more than just ballplayers.

Through his scholarly work, Dr. Cooper investigates the lived experiences of student-athletes of color to help identify major issues impacting their educational experience and develop solutions that will aid in their holistic development and growth. His research is centered around the intersection of sport, race, education, and culture. Dr. Cooper’s research directly informs his work ← ix | x → with student-athletes in the Collective Uplift program – an evidence-based program designed to empower student-athletes of color to maximize their potential for success on and off the field. Dr. Cooper has also written numerous articles and book chapters on athlete activism and HBCU athletics including an edited volume entitled The Athletic Experience at Historically Black College and Universities: Past, Present, and Future.

While this book is a milestone in his career, I am equally as proud of the work he is doing on the ground at UCONN. When he arrived as an assistant professor he immediately started a program to engage Black student-athletes. Collective Uplift does exactly just that. By focusing on behavior modification, athletic identity, leadership, and decision-making, this initiative has quickly become a model across higher education. So, when you read this book understand that this is not solely based on abstract theoretical principles. Rather, it is grounded in his day-to-day work engaging with student-athletes on his campus and across the country.

Dr. Leonard Moore

Associate Vice President of Academic Diversity Initiatives

Professor of History

University of Texas at Austin

I would first like to acknowledge, thank, and praise God, my Lord and Personal Savior Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit that dwells within me. God has blessed me infinitely and everything I do is to honor and glorify Him. Thank you Lord for your endless mercy, grace, and love. I continually seek to draw nearer unto you and fulfill your purposes for my life. I would like to thank my mother, Dr. Jewell Egerton Cooper, for your unconditional and immeasurable love, sacrifices, nurturing, guidance, and support. Throughout my life, you have served as a positive role model and instilled in me timeless values, critical consciousness, and the importance of concerted actions. You role modeled perseverance and determination against challenging odds. I love you and thank you for being the greatest Mom for me and my heroine. To my father, Dr. Armah Jamale Cooper, thank you for loving me, being my father and Dad, and showing how to be a man of faith and perseverance. Your authenticity and growth showed me that life is a journey and the power of forgiveness is transformative. I love you beyond words. To my brother, Adam Roberts Cooper, thank you for always loving, supporting, and being there for me. Life with you as my bigger brother has been a priceless blessing. I love you very much and always seek to make you proud.

To my grandmothers, Mama Jo (Josephine Johnson Egerton Wilkins) and Mama (Izetta Roberts Cooper), I thank and love you for being my spiritual ← xi | xii → anchors. To my grandfathers, Daddy Walter (Walter Eugene Egerton, Jr.) and Papi (Dr. Henry Nehemiah Cooper), I love you and hope I am making you all and all of our ancestors proud. To my entire family including extended members and kinship, thank you for your support and I love you. To Dr. Harry Edwards, thank you for your courage, passion, intellect, scholarship, and activism. You have set the benchmark for revolutionary Black empowerment and struggle in the field of sport sociology and beyond. To all of my teachers, advisors, and mentors, thank you all for the guidance, support, and lessons taught. I hope this book reflects my appreciation to you all for what you have done. To all my friends, thank you for your support, friendship, and helping me grow personally and professionally. To all my classmates and colleagues, thank you all for sharing your journeys with me and helping me grow as a learner, critical thinker, writer, communicator, scholar, educator, and activist. Last, but certainly not least, to my lovely and amazing wife, Monique Shari Cooper, thank you for being in my life and loving me the way you do. Our love is one of kind and means more to me than words could ever express. You make me a better child of God, person, man, husband, and father. I love our life, marriage, and family.

To really honor the struggles of the past, however, the ultimate goal must be to create a new and better model, not to replace an old form of oppression with a new one

— Rhoden (2006, p. 195)

The Plight of Black Males in the United States: Conditions, Realities, and Complexities In and Through Sport and Beyond

The dire conditions facing and subsequent outcomes associated with Black1 males in the United States (U.S.) has been well-documented (Curry, 2017; ETS, 2011; Howard, 2014; Jackson & Moore, 2006; Noguera, 2008). These circumstances include high incarceration and juvenile detention rates, school truancy and attrition rates, overrepresentation in special education and concurrent underrepresentation in gifted programs in the K-12 educational system, persistent health issues (e.g., depression, high blood pressure, diagnosed mental disorders, etc.), cyclical economic deprivation and immobility, and higher mortality rates and shorter lifespans compared to peers (within and outside of their own race and gender groups)—collectively, these outcomes ← 1 | 2 → reflect “social symptoms of a history of oppression” (Majors & Billson, 1992, p. 12). Another alarming, albeit typically perceived as innocuous, trend among Black males is what Edwards’ (2000) calls their obsession with sports. According to Edwards (2000), Black males’ obsession with sports results in a triple tragedy: (1) a fixated pursuit of a professional sports career a vast majority of them will not attain, (2) overall identity and skill underdevelopment of Black male former athletes, and (3) a lack of optimal improvements within the Black community due to the talent extraction towards sports and away from vital occupational fields such as health, law, business, politics, education, and technology to name a few. Unfortunately in the U.S., there are few spaces where Black males are valued, supported, and celebrated and sport is one of them. For example, it is not uncommon for a local town or city to declare a holiday or rename a street for a former standout athlete, but this same of recognition is seldom if ever applied for non-athletic accomplishments. Although, this practice occurs in communities across racial lines, the implications for Black males is particularly problematic given the previously cited social realities that position them among the most disadvantaged group in a society founded upon and structured by the ideology of White racism capitalism2 (WRC).

Despite widespread success in sporting realms, namely in football, basketball, and track and field across all levels (e.g., youth, interscholastic, intercollegiate, and professional), many scholars have argued sport serves more as a site for exploitation consistent with the American tradition of commodifying Black male bodies for the financial and entertainment benefits of Whites rather than for the collective racial, social, political, and economic uplift and sustainability of Blacks (Cooper, 2012; Cooper, Macaulay, & Rodriguez, 2017; Edwards, 1969, 1973, 1984, 2000; Hawkins, 2010; Rhoden, 2006; Powell, 2008; Sellers, 2000; Smith, 2009). Polite (2011) defined exploitation as “the unfair treatment or use of, or the practice of taking selfish or unfair advantage of, a person or situation, usually for personal gain” (p. 2). Within the context of the U.S., exploitation and racial discrimination are inextricably linked. Franklin and Resnik (1973) outlined this relationship with the following definition: “Discrimination in the context of the American society, given its racial heritage, involves antipathetic distinctions that are made systematically (in contrast to randomly made-distinctions) by a dominant white majority to the disadvantage of a subordinate black minority” (p. 16). The four mechanisms by which discrimination is institutionalized in society are through state sanctioning (e.g., laws, policies, statutes, etc.), social preferences (both ← 2 | 3 → non-violent and violent), stereotyping, and market conditions (Franklin & Resnik, 1973). Each of these four mechanisms operate on multiple levels in society (macro, meso, and micro) and influence the purpose and structure of social institutions such as sport and education. Suffice it to say Black males’ presence in organized sports has been contested since their initial involvement dating back to the mid-1800s (Edwards, 1973; Wiggins, 2014; Wiggins & Miller, 2003). Thus, sport has served as both a site for ideological and social reproduction as well as a space for resistance and transformation in regards to race, class, and power relations (Cooper et al., 2017; Edwards, 1969, 1973, 1980, 2016; Hartmann, 2000).

Notwithstanding the aforementioned complexities, previous research and popular discourse on Black male athletes’ socialization experiences and outcomes has been conspicuously limited. Consequently, distorted generalizations of these processes have been widely accepted without a critical examination of the heterogeneity among this sub-group (e.g., all Black males being viewed as sport obsessed, academically deficient, economically impoverished, etc.). In disciplines outside of sport sociology, scholars have asserted the danger of promoting and accepting homogenous narratives of entire racial and gender groups (Celious & Oyserman, 2001; Harper & Nichols, 2008). Even when acknowledging negative outcomes associated with Black males, it is important to recall Edwards’ (1984) prophetic message: “Dumb jocks are not born, but rather they are systematically created and the system must change” (p. 8). Hence, the aim of this book is to offer a paradigm shift by outlining five models of Black male socialization in and through sport and (mis) education3 within a comprehensive historical, sociocultural, political, and economic context while offering a modernized blueprint for positive progress centered on holistic development.4 These socialization models build upon previous literature and address both Edwards’ (1984) call for a systems change and Rhoden’s (2006) charge of creating new models that challenge rather than reproduce individual holistic underdevelopment and group oppression. The paradigm shift is a call to action to alter sporting and educational spaces from sites of exploitation and miseducation to sites of empowerment and sustained collective vitality for Black male athletes and the broader Black community.

Related to the proposed socialization models and contrary to stereotypical assertions, Black male athletes are not monolithic. Yet, the dominant narratives, popular discourses, and vast majority of scholarly literature on this sub-group has situated them in a narrow scope. These sources have primarily focused on Black male athletes’ early socialization into athletics, keen ← 3 | 4 → attraction towards sport glory via positive identity affirmation, concurrent academic underperformance, athletic role engulfment and identity foreclosure, career immaturity, financial illiteracy, and overall underdevelopment and exploitation (Adler & Adler, 1991; Beamon, 2008, 2010, 2012; Beamon & Bell, 2002, 2011; Benson, 2000; Brooks & Althouse, 2000, 2013; Eitle & Eitle, 2002; Harris, 1994; Hawkins, 2010; May, 2008; Sellers, 2000; Sellers, Kuperminc, & Waddell, 1991; Singer & May, 2010; Smith, 2009). While the harsh reality of Black male athletes being exploited across all levels (youth to professional) occurs all too frequently, these descriptions only reflect a subset of the lived experiences of the broader group of Black male athletes in and through sport and (mis)education.

A few notable exceptions have highlighted Black male athletes who were politically conscious and engaged in social justice efforts, but this exploration has largely been limited to Black athlete activism during the Civil Rights Movement and more recently post-Colin Kaepernick’s symbolic kneeling gesture in the Black Lives Matter (BLM) era (Cooper et al., 2017; Edwards, 1969, 1980, 2016). Moreover, additional noteworthy works have incorporated anti-deficit approaches in the examination of how Black male athletes navigate contested educational terrains and experience high levels of academic and career success beyond sporting spaces (Bimper, 2015, 2016, 2017; Bimper & Harrison, 2011; Cooper, 2016, 2017; Cooper & Cooper, 2015 Cooper & Hawkins, 2014; Harrison, Martin, & Fuller, 2015; Martin, Harrison, Stone, & Lawrence, 2010; Oseguera, 2010; Smith, Clark, & Harrison, 2014). Despite the benefits of these studies, they offer a polar opposite perspective of Black male athletes’ experiences in academic and athletic milieu (i.e., “dumbs jocks” vs. scholar athletes). Given the diversity of experiences among Black male athletes, there is a need for more nuanced coverage of their socialization experiences and subsequent life outcomes. Such analyses would provide vital insights for understanding how specific systems, conditions, and processes contribute to Black male athletes’ holistic (under)5 development.

Foundation for Understanding Black Masculinities In and Through Sport and (Mis)Education

Black masculinities is a complex phenomenon that has been explored across various disciplines such as gender studies (Staples, 1978; Summers, 2004), sociology (DuBois, 1903/2003), philosophy (Curry, 2017; Fanon, 1952/2008), ← 4 | 5 → cultural studies (Bush & Bush, 2013a, 2013b; Mutua, 2006), urban education (Howard, 2014; Majors & Billson, 1992; Noguera, 2008), postsecondary education (Cuyjet, 2006; Douglas, 2016; Harper, 2012; Harper & Harris, 2010; Harper & Nichols, 2008; Wood & Palmer, 2014), and sport to name a few (Armstrong & Jennings, 2018; Edwards, 1969, 1973; Harrison, Harrison, & Moore, 2002; Hodge, Burden, Robinson, & Bennett, 2008). The aforementioned interdisciplinary attention towards Black masculinities has examined the nuances associated with biology, anatomy, physiology, ecology, ethnology, anthropology, geography, culture, time, psychology, identity, social constructions, and political economies. In concert with these transdisciplinary approaches, I surmise any theory of Black masculinities and corresponding socialization processes must take into account socio-historical and socio-cultural contexts, which shape meanings both internally, externally, temporally, and in perpetuity. Otherwise stated, Black masculinities do not exist or function in a vacuum, but rather in tandem with identity constructions and social realities.6

In an examination of scholarship on Black masculinities, Summers (2004) outlined three distinguishable paradigms. The social science paradigm situates Black masculinities in relation to oppressive structures such as educational institutions, criminal justice system, and different economic sectors (e.g., prisons, sports, etc.). Within this paradigm, Black masculinities are characterized by surveillance, control, and exploitation. These works utilize statistical data and anecdotal narratives and stories to illustrate the nature and extent of Black males’ identity development and the conditions therein (Summers, 2004). The discursive paradigm explores the identity construction of Black males through representations in the dominant culture with a particular emphasis on power dynamics and race relations. The historical and dichotomous images of Black males as docile sambos or violent brutes in White mainstream media dating back to the early 19th century through the early 21st century are examples of research within this paradigm (Hawkins, 1998a, 1998b; Sailes, 2010).

The historical paradigm focuses on examining Black masculinities within a broader narrative of African Diasporic (including African American) experiences (Summers, 2004). These works explore how Black masculinities were and remain constructed within the socio-cultural and geopolitical contexts across specific eras in human history. The delineation of the era muscular assimilationism during the latter 19th and early 20th century versus the era of cultural nationalism in the early to mid-20th century in the U.S. and their respective influences on Black masculinities within and beyond sport illustrate analyses ← 5 | 6 → associated with the historical paradigm (discussed in greater detail in Chapter 1). Throughout this book, each of the three paradigms are strategically incorporated to reflect my social constructivist epistemological stance as well as my pluralistic proclivities when seeking to understand complex phenomena (the concept of theoretical pluralism is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3).

My Positionality

The inspiration for my research and this book stem from my subjectivities and life experiences as a Black and African American male who grew up in a Southern Baptist household with my mother and older brother (parents were divorced in my pre-teens and my father lived nearby). During my youth, a significant part of my self-identity was connected to my athletic abilities and accomplishments namely in basketball and soccer. In my home state of North Carolina, basketball is a way of life. Numerous Black males aspired to be the next Michael Jordan and play at one of the Tobacco Road schools (University of North Carolina, Duke University, North Carolina State University, or Wake Forest University). In fact, it was not a surprise for any of us in the elite basketball circuit to know or be the star who earned a Division I scholarship or make it to the professional ranks (as of 2018, three of the top 10 point guards in the National Basketball Association (NBA) are from North Carolina and they are all 6′4 inches or shorter—Stephen Curry, Chris Paul, and John Wall; thus illustrating the magnitude of basketball talent and emphasis in the state).

It was not until my playing days were over when I experienced a range of psychosocial challenges due to my reduced athletic status that I came to the realization that being an athlete was only a small part of my identity. In my professional experiences working with Black males, I have learned that many of them share similar experiences in regards to primarily self-identifying as an athlete. As a mentor, I personally connected with my mentees when they described their aspirations of becoming professional athletes as well as their frustrations with being treated differently by others because of their race, ethnicity, gender, and athletic status. As a researcher, I also began to identify common themes in the literature and media coverage of Black male athletes. These common themes included experiences with racial discrimination, social isolation, academic neglect, economic deprivation, and limited leadership opportunities (Cooper, 2012). These trends caused me to question the socialization patterns of young Black males in the U.S. I concluded the underlying problem lies in the fact that young Black males are socialized to ← 6 | 7 → be athletes at the expense of their holistic development. My affinity for history, sociology, sport, culture, and education grew during my undergraduate years when I majored in Sociology and Recreation Administration. I later earned my Master’s degree in Sport Administration and completed my thesis titled “The Relationship Between the Critical Success Factors and Academic and Athletic Success: A Quantitative Case Study of Black Male Football Student-Athletes at a Major Division I Southeastern Institution” (Cooper, 2009). In 2013, I completed my doctorate at the University of Georgia and my dissertation was titled, “A Mixed Methods Exploratory Study of Black Male Student Athletes’ Experiences at a Historically Black University” (Cooper, 2013). My first published manuscript was titled, “Personal Troubles and Public Issues: A Sociological Imagination of Black Athletes’ Experiences at Predominantly White Institutions in the United States” (Cooper, 2012). Thus, my epistemological, axiological, ontological, theoretical, and methodological orientations underscore my subjectivities and influence my research.

Moreover, I contend the paradox regarding Black male athletes’ experiences with athletic identity foreclosure is reflective of broader systemic inequalities within the U.S. society based on historical patterns of racial discrimination, exploitation, and marginalization of Blacks in general and Black males more specifically. Thus, my research interests are a byproduct of the intersections between my personal background, multiple identities, experiences, exposures, resources, and various ecological and socio-historical factors. The fact that I am a Black and African American male plays a significant role in my research interest in Black male athletes. In addition, my experiences as a former athlete provide me with a distinct lens for examining the impact of sport participation on Black male athletes’ academic achievement, self-identity, psychosocial well-being, holistic experiences, and post-athletic career outcomes. I fully acknowledge, accept, and embrace my unique positionality as a researcher of Black male athletes. A goal of my research is to empower those who are disadvantaged by current social structures, arrangements, and practices. Consistent with social constructivism, I assert that my subjectivities strengthen my research rather than constrain it.

The Need for Critical Sociological and Ecological Examinations of Black Male Athletes

In order to understand the experiences of Black male athletes, two important foci area must be examined and understood. First, a critical sociological ← 7 | 8 → examination of historical, sociocultural, political, economic, and educational occurrences in the U.S. society is required (Chapters 1 and 2). A major omission from popular discourse on Black male athletes is the lack of contextualization regarding their sport involvement and educational (dis)engagement in connection to broader societal realities. Thus, historical research that situates sport and education within a critical sociological apparatus undergirds the five models presented in this text. For example, when analyzing the history of Black athlete activism in the U.S., Edwards (2016) distinguished events based on the era in which they occurred. The four waves of Black athlete activism that coincided with broader social movements included: (a) first wave (1900–1945) focused on gaining legitimacy, (b) second wave (1946–1960s) centered on acquiring political access and diversity, (c) third wave (mid-1960s–1970s) championed demanding dignity and respect, a period of stagnation (1970s–2005) occurred in the late 20th and early 21st century, and (d) fourth wave (2005-present) shifted attention towards securing and transferring power via economic and technological capital. Broader social movements that occurred concurrently during these eras included the Ante-Bellum Period movement (early 1800s–1860s), Black Liberation movement through Reconstruction (1880s–1920s), Harlem Renaissance Era (1920s–1930s), Black Integration movement (1930s–1960s), Civil Rights movement (1960s), Black Power and Black Feminism movements (late 1960s–1980s), and Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement (2010s) (Cooper, Mallery, & Macaulay, forthcoming). Similar to Edwards’ (2016) contextualization of Black athlete activism, I assert critical socio-historical analyses are needed for understanding how and why specific experiences and outcomes manifest among different sub-groups of Black male athletes in the U.S.

The second foci area necessary for understanding Black male athletes’ socialization experiences and outcomes is a multi-level analysis of sub- (spiritual), chrono- (time, space, and location), macro- (societal/global/national), exo- (mass media and indirect entities), meso- (cultural/organizational/institutional), and micro-system factors (individual/interpersonal/ community/family/peer group) (Bronfenbrenner, 1977, 1986; Bush & Bush, 2013a, 2013b). In order to unpack the interlocking influences of social systems, structures, polices, and practices on individual and group schemas, behaviors, experiences, and outcomes, a socio-ecological systems analysis is imperative (Chapter 3). The ways in which Black males experience sport and traditional educational spaces is predicated on sociocultural factors (i.e.., significance of and support for sport and education within the individuals’ family, community, and sub-cultures), economic resources (i.e., access (or lack thereof) to ← 8 | 9 → developmental opportunities beyond sport), and individual factors (i.e, personal identity schemas related to sport and non-sport activities) (Chapters 4–8). In addition, the nature and quality of relationships, exposure, interactions, and related socialization factors are also germane to any analysis of variability in terms of lived experiences and outcomes.

In sum, the same society that produces the apolitical consummate capitalist in Michael Jordan on one end and the revolutionary activist in Dr. Harry Edwards on the other also simultaneously produces dismal educational outcomes for Black males in the K-20 educational system or more accurately referred to as the miseducation schooling system, Rhodes Scholars such as Myron Rolle and Caylin Moore, a prison industrial complex that results in nearly one-third of all inmates being Black males, numerous exemplar professionals across multiple academic and occupational fields who graduate from historically Black colleges and universities7 (HBCUs) as well as historically White institutions8 (HWIs), disconcerting numbers of Black males with psychological trauma, a plethora of transformative inventors, pioneers, and Black males who overcome and navigate oppressive conditions through formal and informal means, disproportionate, alarming, and unnecessary perpetual Black male deaths, and countless upstanding and present husbands, boyfriends, fathers, brothers, uncles, grandfathers, great grandfathers, community members, and leaders.

Among this list, some of the patterns documented are more commonly recognizable based on mass media coverage and prevailing stereotypical schemas. Whereas, another set of the patterns listed may appear mythical or atypical. Despite these varied outcomes among Black males, there has yet to be a comprehensive examination that takes into account the diverse experiences of those who participate in sport and (mis)education starting from youth through adulthood. This book fills this gap. The critical sociological analysis within this text incorporates transdisciplinary theories, which allows for the exploration of the interplay between individuals and groups within multi-level systems and their corresponding socialization experiences and life outcomes. This approach disrupts the current erroneous miscategorization of Black male athletes as homogenous and fosters the recognition of their heterogeneity as well as allows for the identification of key intervention points for transformative change (Chapter 9).

Notes

1. The terms “Black” and “African American” are used interchangeably based on the source. The former term is used to refer to the racial group of people with African descent and socially classified as Black and thus historically subjected to differential treatment on ← 9 | 10 → the basis of this marker. The latter term refers to African Americans who have familial lineage in the U.S. dating back to the early 17th century (Singer, 2015).

2. The common usage of the term White supremacy is intentionally not used here or throughout the book to challenge the underlying fallacious assumptions embedded in this terminology. Imposed superiority via violence, political exploitation, and other forms of oppression and human indignities have been well documented across various disciplines. Thus, the usage of the term White racism capitalism emphasizes the intertwinement and recursive relationship between the source of these imposed inequalities and the nature of how they are manifested in socially constructed ways via ideologies, structures, institutions, policies, practices, and property. A useful analysis of the problematic usage of the term White supremacy is offered by the renowned intellectual and Hip-Hop pioneer KRS-ONE (Knowledge Rules Supreme Over Nearly Everyone—birth name is Lawrence Parker) (Parker, 2016).

3. The phrase (mis)education and miseducation is used to signify formal policies and informal practices/social norms that are de facto well-intentioned, but in actuality contribute to negative holistic underdevelopment and communal outcomes for Blacks as well as various oppressed groups. The parentheses around the word “mis” is used selectively to emphasize the contextual distinction between detrimental conditions and educational processes versus positive conditions and true well-rounded educational processes that foster Black holistic development, racial uplift, and cultural empowerment.

4. I define holistic development as the recognition and healthy nurturance of multiple identities including intentional behaviors that foster positive outcomes for self and one’s own family, community, racial and cultural groups, and a more equitable society.

5. The phrases (under)development and underdevelopment are used to describe negative life outcomes, as a result of oppressive and exploitative conditions and detrimental socializations processes, such as unemployment, career dissatisfaction and interest mismatch, sporadic and chronic depression, mental health issues, financial instability, social isolation/alienation, academic attrition, and engagement in other maladaptive behaviors for self, family, and community. The parentheses around the word “under” is used selectively to emphasize the contextual distinction between negative life outcomes as a result of sport participation and miseducation and positive life outcomes such as holistic development and cultural empowerment as a result of true well-rounded educational processes.

6. Identity constructions referenced here include humanity, sex, gender, race, age, ability, class/socioeconomic status, spiritual identity, and religious identification to name a few. Social realities refer to the conditions people are subjected to experiencing as a result of prevailing dominant ideologies (e.g., White racism, capitalism, heterosexism, etc.) such as poverty, stigmatization, fear, violent and unsafe spaces, etc.

7. The term HBCU is defined as an institution of higher education in the U.S. established prior to 1964 with the primary purpose of providing educational opportunities to Black Americans and whose current student population is at least 50% Black.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 342

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433160905

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433160912

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433160929

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433161551

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433161568

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14655

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (January)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2019. XII, 342 pp., 6 b/w ill., 1 table

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG