Editor Emory O. Jackson, the Birmingham World, and the Fight for Civil Rights in Alabama, 1940-1975

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- Advance praise for Editor Emory O. Jackson, the Birmingham World, and the Fight for Civil Rights in Alabama, 1940–1975

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword by Hank Klibanoff

- Preface: Alabama Has Lost a Giant

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1. Magic City, Tragic City

- Chapter 2. Battle for the Ballot

- Postscript

- Chapter 3. An Act of Civil Disobedience

- Postscript

- Chapter 4. We Demand Equal Education

- Postscript

- Chapter 5. Free by ’63

- Postscript

- Chapter 6. Violence Has Sullied Birmingham’s Magic Name

- Postscript

- Chapter 7. Continue the Journey of Freedom

- Chapter 8. Yet We Go on Fighting

- Index

- Series index

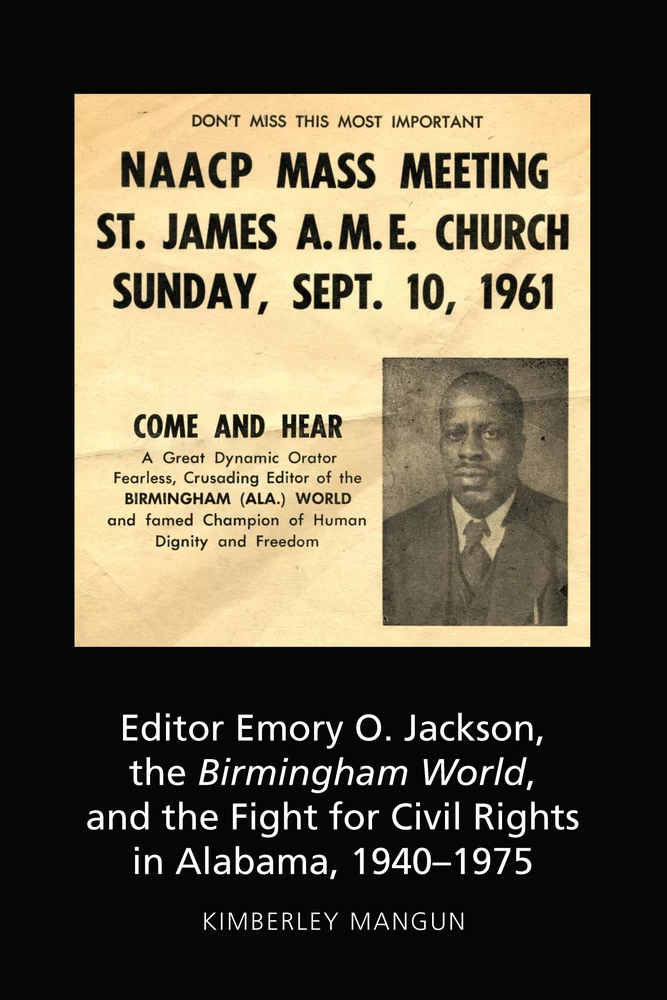

Figure 1.1. Portrait of Emory O. Jackson.

Figure 1.2. Front page of the Birmingham World, September 23, 1952.

Figure 2.1. Emory O. Jackson presents the John B. Russwurm Award to Amelia Boynton.

Figure 3.1. Emory O. Jackson and other civil-rights leaders at the US Supreme Court.

Figure 3.2. Attorney Arthur Shores represents Emory O. Jackson, on trial for seeking to integrate city buses.

Figure 4.1. Emory O. Jackson, Pollie Myers, and Autherine Lucy depart the University of Alabama’s administration building.

Figure 5.1. Emory O. Jackson and his press colleagues pose for a photo in the Oval Office after discussing civil-rights legislation.

Figure 6.1. Birmingham Police Department incident reports.

Figure 7.1. Emory O. Jackson mixes pleasure with business during a brief stay in New York City.

Figure 8.1. Emory O. Jackson seized chances during his career to discuss civil-rights issues with politicians.

We have this problem in much of the rural South: Scores, hundreds, perhaps thousands of Black people who came out of the backwoods, who left farms and hard-scrabble lives, and who succeeded in leaving a national imprint have little acknowledgment or presence today in the communities that nurtured and launched them. These are men and women whose towering achievements are memorialized on signs, plaques and portraits far away from their native homes, but who are no longer known, remembered or celebrated where they lived, walked, played and prayed as children.

Buena Vista, Georgia, produced Josh Gibson, born in 1911, who regularly ranks as perhaps the best Negro Baseball Leagues player of all time. Known as the “Black Babe Ruth,” Gibson was the second Black, behind Satchel Paige, to be inducted in the Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown. He’s even on a postage stamp. But there is no official, public commemoration of his importance in that town, which has doubled in population to 2,000 since Jackson and Gibson’s childhoods.

Same goes for another son of Buena Vista: One of the premier journalists of the civil rights era in the South, Emory Overton Jackson, the fearless, indefatigable and conflicted editor of the Birmingham World, the largest black newspaper in Alabama. He was born in the town due south of Atlanta in 1908, three years before Gibson. ← xi | xii →

Jackson joined the World in 1934 and served as its editor for an extraordinary 35 years, from 1940 until he died in 1975. Put another way, he was editor through a world war that featured Black soldiers and the full desegregation of the military that followed, through the integration of baseball and the drawn-out implementation of Brown v. Board of Education, through the 381-day bus boycott in Montgomery (during which Jackson was privy to information from Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., whom the journalist likened to Mahatma Gandhi). He was editor during the tumultuous desegregation of lily-white University of Alabama (where Jackson was an inspiration to Autherine Lucy, who broke the color line in 1956), through the national embarrassment of Birmingham firefighters and police officers mowing down kids and adults with high-powered fire hoses and vicious dogs on the streets of Birmingham, and then through the national horror of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing that claimed the lives of four young girls. Through all this, Emory Jackson was the gumshoe editor of a scantily-staffed semiweekly newspaper who put himself on assignment every day and who claimed the foremost front-row seat on history as the civil rights struggle evolved into a movement before the world’s eyes.

Emory Jackson is celebrated on a plaque in downtown Birmingham where the Birmingham World newsroom was located, on a portrait at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, in several Pulitzer Prize-winning books, and in civil rights archives from Atlanta to Berkeley to Washington, D.C. But in his birthplace, Buena Vista? “That’s just not a name I know,” says the probate judge in Marion County when I asked about Jackson. Hers was a concession, maybe even a confession, I would hear again and again when I visited Buena Vista.

But on the lawn of the 168-year old Marion County courthouse and again inside the courthouse, there is one Buena Vistan honored and not so easily forgotten: Luther H. Story, a White Army soldier whose heroics in battle in the Korean Conflict in 1950 earned him a Medal of Honor and cost him his life.

The meaning of this celebration of White heroes and disregard for Black ones? There’s no way Emory Jackson could have known whether he’d be remembered in his hometown, but here’s why I think he saw it coming. Even after seeing so many of the walls of White supremacy crumble and fall in Alabama, he had a wise and prescient sense of how history would treat men like Josh Gibson and himself. “The devaluation of a group,” Jackson said in a talk in 1972, three years before he died, “often begins with the denial of their history.” ← xii | xiii →

Now, thanks to the equally indefatigable Dr. Kimberley Mangun, a journalism historian who has immersed herself for nearly ten years in the life and times of Emory O. Jackson, we have an opportunity to see, closely and comprehensively, one man’s battle in the state of Alabama—one Black newspaperman’s battle, to be specific—to provide his people, his community with the steady and relentless flow of news coverage and commentary that reflected the value and the meaning of their lives at a momentous time and place in history. Please note that I did not say Emory Jackson’s newspaper gave meaning and value to the lives of Blacks in Alabama. They brought that with them. Jackson assiduously presented, showcased and revealed the value and meaning he knew already existed in those lives—which he also knew were ignored and even disdained by the White owners and editors at the major metropolitan daily newspapers in Birmingham. The Birmingham World, each week, was a celebration of Black success and achievement, a slap at White supremacist violence inflicted on his people, and a reflection of an editor torn by conflicting emotions over the best strategy for defeating the evils of racism.

The span of Jackson’s life, just shy of seven decades, coincided with the emergence and establishment of multiple movements among Black Americans—the gradualism of Booker T. Washington, the Black nationalism of Marcus Garvey, the biracial origins of the NAACP, the more assertive agitation of A. Philip Randolph, the nonviolent strategy of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., the forceful rhetoric of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the ramped-up oratory of the Black power movement, and the even more aggressive threats of confrontation from the Black Panthers. Each of those was a juggernaut, and when they were churning forward in overlapping time, they shook the earth.

Each movement placed new demands on Black newspaper editors, and threw new hurdles in front of them. From where Jackson sat, he could see plenty of generational or economic disagreements among major factions in the Black communities; but even without those divisions, editors could see that every engagement—over transportation, schools, public accommodations, voting—produced multiple and conflicting strategic options for advocacy. Direct action? Litigation? Appeal? Withdraw? There were as many disagreements as agreements on these among Blacks in Birmingham and across the South. In the Black community, the person expected to know the answers was the editor of the Black newspaper. The editors shared that role and conflict with Black pastors. In some ways, it’s easier to understand the challenges Black editors faced by looking not at their newspaper audiences but at the churches. The ← xiii | xiv → political divisions between staid churches that drew their congregations from the professional elite and more activist churches whose poorer congregants had less to lose kept Emory Jackson and other Black editors constantly off balance—until their one common adversary, White segregationists, reliably overplayed their hand, reverted again and again to violence, and made it easier for Black factions to coalesce against the brutal hand of White supremacy.

Dr. Mangun, backed by prodigious research that all historians should model, has put together a clear and comprehensive examination not simply of an editor, but an editor in the eye of the fiercest racial storms in the South, an editor trying to find meaning in all the fast-paced events swirling around him, then trying to make sense of them.

Emory Jackson, Dr. Mangun informs us, expressed his visceral response to the violence that accompanied White supremacy in his clear and sometimes angry personal columns each and every week, and yet he confounded many in the struggle. Jackson, sometimes in tortured language that might have been evidence of his conflicted heart, opposed Dr. King’s call for direct action, in the streets, to confront the repressive White establishment of Birmingham. In King’s mind, a face-to-face street confrontation between trigger-happy Birmingham police and his own demonstrably non-violent forces—even if it ended in a stalemate—would be a victory for civil rights. In Emory Jackson’s mind, such demonstrations were “wasteful and worthless.” He called them “mass action stunts.”

This is a book of stories, stories that present Jackson as a man constantly swinging between his time and ahead of his time, a man whose high standards of journalism led him to blow up about typos and misspelled words, then to become almost paralyzed and unable to report when some big stories were breaking all around him. Dr. Mangun has given all of Jackson’s writings the closest possible reading, and done it so expertly that she analyzes not merely what he did write, but also what he didn’t cover.

This is a book that Dr. Mangun alternately curses and thanks me for getting her into. I was smitten by the Emory Jackson story when I researched him for a book that became The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation (Knopf, 2006, Vintage 2007). In a book that covered multiple news organization and journalists over a three-decade period, I was not able to give Emory Jackson as much attention as I wanted. I felt I captured only a piece of him. When Dr. Mangun asked me what character I wished I could have spent more time researching and writing, I blurted Emory Jackson’s name. ← xiv | xv →

So now, all these exhausting years of research later, I am happy to see that not only has Dr. Mangun written a book about the Emory Jackson who lived from 1908 til 1975; she’s also described, in small but important interstitial postscripts to her chapters, the enduring legacy of Emory Jackson all these years later. In other words, she’s overcome the absence of his presence in Buena Vista by telling us this important man’s legacy.

While Dr. Mangun may curse me for the way the book has occupied her life, all I can do is admire her, thank her, and say she has found the stories I never knew, never heard and never imagined. She found the whole Emory Jackson.

Hank Klibanoff is co-author of The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation, which was the 2007 Pulitzer Prize winner in History. He directs the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project at Emory University, where he is also a professor of practice in the Creative Writing Program/nonfiction. Klibanoff created and narrates Buried Truths, a narrative-history podcast available on iTunes.

Rosa Parks sat down in her Detroit home on September 16, 1975, and wrote a sympathy note to the family of Emory Overton Jackson. “I think of him as one of the great men of our time; as one dedicated to freedom and equality of all oppressed peoples. Much of my inspiration came from knowing and working with him … before it was popular to speak out against injustice.” That day in Birmingham, Alabama, hundreds of people from across the country gathered at Sixth Avenue Baptist Church to pay their last respects to the managing editor of the Birmingham World, who had succumbed to prostate cancer a week earlier at the age of 67.1

Benjamin Mays, president emeritus of Morehouse College in Atlanta, delivered the eulogy. Jackson stood tall, he said, and was unafraid to speak the truth and take a stand in the fight against discrimination and segregation. He was a leader in the community before Fred Shuttlesworth, founder of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, and Martin Luther King Jr. took charge of the civil-rights movement in Birmingham. Jackson, said Mays, had his own dream that one day Black people would be free.2

Other speakers, such as Jet associate publisher Robert Johnson, lined up to share stories about Jackson’s influence on their lives and careers. And Jackson’s employer, Atlanta Daily World publisher Cornelius (C. A.) Scott, paid tribute ← xvii | xviii → to the strong-willed man who was by turns brusque and compassionate, frugal and generous, funny and critical.3

Jackson was buried at Shadow Lawn Memorial Gardens. His parents, grandmother, and a sister also were interred at the historically Black cemetery in southwest Birmingham.4 I stopped by the site on a warm September afternoon in 2012 with Jackson’s youngest brother, Lovell. A locked gate prevented access by car and Lovell, then 90, was unable to walk on uneven paths through the neglected cemetery to try to find Emory’s grave. Lovell was visiting his hometown from Detroit, the third trip in 13 months, to urge city officials to memorialize his late brother.5 The timing finally was right: Birmingham was preparing to observe the 50th anniversary of the civil-rights events of 1963 that brought national attention to the city. A large plaque featuring biographical details and an image of Jackson seated at his desk is now affixed to the brick facade of the former site of the World office on 17th Street North.6 That it took 37 years to recognize the editor and his advocacy of equality for Black Alabamians is disheartening. Many of the individuals who sent notes and telegrams to Jackson’s family upon his death were confident that his place in the history of the Civil Rights Movement was secure, especially since his 35-year career as a newsman and civil-rights advocate was documented in the Birmingham World and other Black newspapers.

The city may have been slow to honor Jackson, but he didn’t altogether escape notice after his death. A few authors, such as Culpepper Clark, Diane McWhorter, J. Mills Thornton III, and Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, acknowledge Jackson’s “born for battle” personality and roll-up-your-sleeves style of journalism that was critical for keeping the Black community informed about issues including voter-registration drives, poll tax deadlines, NAACP meetings, and legal battles against segregated schools, neighborhoods, and transportation.7

This cultural biography, the first full-length scholarly book about Emory O. Jackson and the Birmingham World, expands on previous mentions of him and situates the editor and his advocacy in the long political and social struggle for civil rights that played out—often very violently—in Alabama. By examining how the era and culture both defined and constrained him as a man, editor, and civil-rights activist, I hope to show the complexity of his work and character and illustrate why even steadfast supporters of equality like Jackson could have a conflicted approach to the Civil Rights Movement. This cultural biography contributes to the growing field of scholarship on the ← xviii | xix → Black Press and the struggle for equality in the United States and provides historical background for #BlackLivesMatter and ongoing discussions of equal rights and justice in education, policing, and voting.

The book highlights some of the key short- and long-term campaigns that Jackson waged or covered during his career and their implications for Blacks in Birmingham, in Alabama, and in the South. For example, Chapter 2 focuses on the fight he led from 1945–1951 against the disenfranchising Boswell Amendment and its successors. Scholars have paid them little attention, but the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People considered them crucial to the freedom struggle because Georgia and other Southern states were attempting to institute similar restrictions on Black suffrage. Jackson wrote editorials and columns about the amendment that required prospective voters to understand and explain the US Constitution to the satisfaction of county boards of registrars. He spoke to groups throughout Alabama to educate them about the dangers of the bill. After it passed, Jackson raised money for a lawsuit brought by the NAACP’s Special Counsel Thurgood Marshall and local civil-rights attorney Arthur Shores alleging a violation of constitutional rights. Despite a federal ruling in a related suit that held the Boswell Amendment unconstitutional, a decision that was upheld by the US Supreme Court, White politicians in Alabama devised other ways to limit Blacks’ ability to register to vote. Jackson documented voter discrimination in the Birmingham World and reported denials by boards of registrars to the Department of Justice, the NAACP, and other organizations. The protracted fight for the ballot described in Chapter 2 illustrates concerted attempts by Alabama’s White populace to stem the tide of post-World War II voter registration and demonstrates Jackson’s assertion of constitutional rights in postwar America.

Details

- Pages

- XXVIII, 268

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433148057

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433148064

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433148071

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433148026

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433148033

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15454

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (October)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2019. XXVIII, 268 pp., 9 b/w ill., 1 color ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG