Non-Violent Resistance

Counter-Discourse in Irish Culture

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

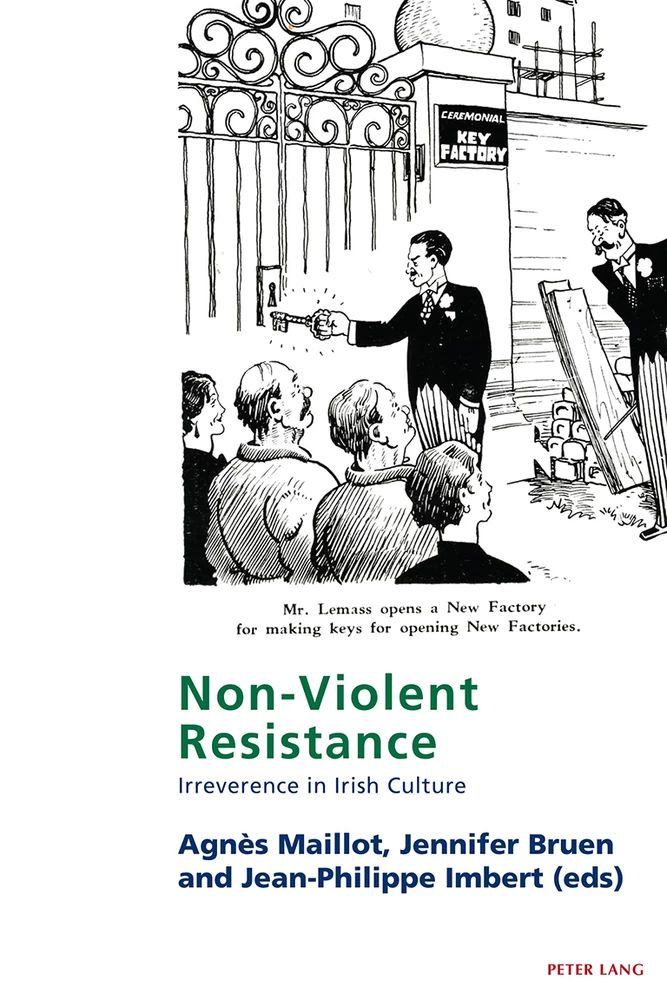

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction: Counter-Discourses, Counter Arguments, and New Paradigms (Jennifer Bruen)

- Part I: Subverting the Political Mainstream

- 1 Police Informers and Spies versus Irish Violent Agrarian Societies: A Non-Violent Secret Alternative to Rebellion (Emilie Berthillot)

- Violent Irish Rebels versus Undercover Police Officers

- The Danger Represented by Starving Irish Peasants

- Traditional Rituals: The Inner Workings of Secret Societies

- A New Mission for Police Forces: Keeping Irish Activists under Scrutiny

- Police Forces or Secret Services

- The Downfall of the RIC

- Surveillance Mission: The End of Legitimacy

- Irish Rebels: The Instigators of British Secret Services

- 2 ‘A Calculated Instrument of Reprisal’: Irish Parliamentary Obstructionism (1874–1887) (Pauline Collombier-Lakeman)

- How Did the Irish MPs Use Obstruction? A Few Examples

- A Divisive Strategy in Irish Nationalist Circles

- Britain Grappling with the Problem of the Irish obstructionists

- 3 ‘Mixed-Up Mess of a Botched Family’: Re-Locating ‘The Family’ in Siobhán Parkinson’s Teen Novel Sisters … No Way! (Åke Persson)

- ‘The Family’ in Irish Society

- ‘The Family’ Re-Examined in Sisters … No Way!: Discourses and Counter-Discourses

- Conclusion

- Part II: Conflicting Discourses in Northern Ireland

- 4 Counter-Discourse as Dialogue Invitation: Reappraising Archbishop Ó Fiaich’s ‘Slums of Calcutta’ Speech (Jan Freytag)

- 5 Counter-Discourse and Irreverence in a Context of Political Reconciliation: The Example of Ian Paisley and the DUP (Magali Dexpert)

- Counter-Discourse in a Context of Political Appeasement

- Attack is the Best Form of Defence: The Targets of the DUP’s Counter-Discourse During the Peace Process

- Counter-Discourse as a Powerful Device to Seduce the Electorate

- Conclusion

- 6 A Study of Mary O’Donnell’s ‘Storm over Belfast’ and Where They Lie from the Perspective of Classic and Pluralistic Trauma Discourses (José Manuel Estévez-Saá)

- 7 Counter-Discourse and Political Violence: Belfast in ’71 and A Belfast Story (Stéphanie Schwerter)

- Navigating the Maze of the Streets of Belfast in Demange’s ’71

- Resurging Violence in A Belfast Story

- Conclusion

- Part III: Challenging Dominant Discourses in Irish Society

- 8 Irish Dissenting Priests and the Renewal of the Church (Perhaps) (Catherine Maignant)

- Background and Timeline

- Irreverence, What Irreverence?

- Marching Backwards Into the Future?

- 9 Counter Hegemonic Discourses on Institutional Abuse in Ireland (Nathalie Sebbane)

- Gramsci’s Theory of Hegemony

- Applying Gramsci’s Theory to the Institutionalisation of Vulnerable Groups in Ireland

- Challenging Hegemonic Discourses

- Counter-Hegemonic Discourses and Sites of Resistance

- Conclusion

- 10 Emerging, Submerging Lesbians in Ireland (Mel Duffy)

- Methodology

- Growing Up in Ireland

- Stirrings

- Secrets

- Mental Health

- Risk of Who Knew

- Becoming Oneself

- The Social Construction of Women’s Situation

- Rose-Tinted Glasses

- Conclusion

- Part IV: Provocation in Poetry and Performance

- 11 ‘Resistance Days’: From Dark Interiors of Resistance to the Disobedient Resistance of Raw Materials in Derek Mahon’s Poetry (Marion Naugrette-Fournier)

- ‘Punctum’ Versus ‘Studium’: The Poem as Photographic Developer

- The Dark Interiors of Resistance

- The Resistance of the ‘Mute Phenomena’

- The Disobedient Resistance of Raw Materials

- 12 Christy Moore on Stage: Loss, Echoes and Movement (Jeanne-Marie Carton-Charon)

- Loss and Protest

- Echoes

- Movement

- 13 Dialogues des Morts: A Subversive Representation of Hades in an Eighteenth-Century Irish Manuscript (Pádraig Ó Liatháin)

- Eachtra Ghiolla an Amaráin: Reception, Content, Transmission

- Virgil’s Aeneid and its Transmission in Irish-Language Literature

- The Underworld, Donncha Rua and the Aeneid

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Series index

Introduction: Counter-Discourses, Counter Arguments, and New Paradigms

For last year’s words belong to last year’s language

And next year’s words await another voice.

— T. S. ELIOT, ‘Little Gidding’, Four Quartets (New York, 1943)

The prevailing discourse of any time influences and is influenced by how those engaging with it perceive the world around them. As the established, dominant discourse, it also, by definition, expresses mainstream values, norms, beliefs and attitudes, be they in relation to historical events or contemporary social and political structures. Competing with the prevailing discourse, to a greater or lesser extent, are other discourses. These give voice to other ways of thinking, other perspectives and alternative worldviews. They are the embodiment in language of opposing arguments, new perspectives and new paradigms. Over time, counter-discourses have both emerged from and acted as drivers of change, progress and social transformation. They constitute a non-violent form of resistance to the norm and to mainstream representations of the world.

Counter-discourses have turbulent existences, competing with the established views held by the powerful. Ultimately, many have come to replace dominant discourses as perceptions of the world change and have themselves come to represent the norm. In turn, they may face competing new counter-discourses as a relentless cycle of change, and sometimes progress, continues. Counter-discourses are fundamental vehicles for independent thought. The purpose of this volume is to acknowledge and pay tribute to their power as non-violent means of resistance to the ‘taken-for-granted’, as drivers of social and political transformation, and as linguistic mirrors reflecting such transformation. ← 1 | 2 →

The volume provides diverse examples of non-violent resistance by means of counter-discourses from myriad domains in an Irish context. These range from the political, to the social, to the cultural. The first section contains three contrasting examples. These represent different types of counter-discourses and their subversion of mainstream thought regarding the political status quo.

Berthillot’s essay, ‘Police Informers and Spies versus Irish Violent Agrarian Societies: A Non-Violent Secret Alternative to Rebellion’, highlights the emergence of an approach designed to counter violent action with a means other than a similar form of aggression, namely infiltration. This increased reliance on surveillance and infiltration of violent organisations has shaped counter action to violence ever since, well beyond Irish shores. It has also changed dramatically our understanding of the term ‘law enforcement’ itself. As Berthillot observes, despite causing issues around the authority and the legitimacy of the police force among the Irish population, ‘a tradition of resorting to informants, infiltrated agents, spies and double-agents in British counteraction had nonetheless been born’.

The second paper, ‘“A Calculated Instrument of Reprisal”: Irish Parliamentary Obstructionism (1874–1887)’, demonstrates how the creative use of discourse itself could bring about change. Collombier-Lakeman focuses on the concept of ‘disruptive-discourse’ and in particular the role played by dissident Irish MPs who resorted to obstructing parliamentary processes using various linguistic tactics to interrupt and slow down debates between 1876 and 1878 and again in 1880–1881 and 1887. The impact of this subversive ‘obstructionism’ led to both the rise of a new Irish leader, in Parnell, and to a radical reform of the way in which debates were conducted in the British House of Commons.

Thirdly, Persson in ‘“Mixed-Up Mess of a Botched Family”: Re-Locating “The Family” in Siobhán Parkinson’s Teen Novel Sisters … No Way!’ shifts the focus to the family, stressing its centrality to Irish identity-formation arising partially out of the protection afforded to the traditional family unit and the Catholic Church by the Irish constitution of 1937. Persson’s article analyses how this novel, aimed at young adults, both showcases and critiques mainstream discourse around divorce and remarriage in the context of the debate on the divorce referendum in Ireland. Persson demonstrates ← 2 | 3 → how Parkinson’s novel introduces an alternative perspective to that of the mainstream by using the diary entries of the two soon-to-be step-sisters at the heart of this narrative.

The second section relates to Northern Ireland and specifically to the nature and role of counter-discourses during the conflict. Freytag, for example, argues for an alternative take on Archbishop Ó Fiaich’s ‘Slums of Calcutta’ statement. His reading of this well-known speech runs contrary to its established interpretations by both the British authorities and the republican movement. As a result, Freytag questions and causes us to question such binary readings of this text.

In the next article, Dexpert examines the text of speeches given by former Democratic Unionist Party leader, Dr Ian Paisley, between 1995 and 2007. Her contribution, ‘Irreverent Political Discourse in a Context of Political Reconciliation: The Example of Ian Paisley and the DUP’, focuses on the late DUP leader’s attacks on political appeasement and the peace process itself. She also considers the relationship between these counter-discourses and the dominant narrative promoting peace and reconciliation, as well as their impact on the electorate.

Estévez-Saá, in ‘A Study of Mary O’Donnell’s “Storm over Belfast” and Where They Lie from the Perspective of Classic and Pluralistic Trauma Discourses’, also questions a mainstream discourse, this time one which is centred on moving forwards, progress and prosperity or on what Estévez-Saá describes as forgetfulness or ‘forgetting’. This paper highlights an alternative discourse, one which is more nuanced and complex, that appears in the work of Irish writer Mary O’Donnell, who concerns herself with unresolved individual, collective and transgenerational traumatic legacies in her short story ‘Storm over Belfast’ (2008), and in her novel Where They Lie (2014). In both texts, the focus is on a fictionalized treatment of ‘the Disappeared’, their families and friends.

Fourthly, and again highlighting the complexities of the Northern Ireland Troubles, Stéphanie Schwerter in ‘Counter-discourse and Political Violence: Belfast in ’71 and A Belfast Story’ focuses on two films, one set at the beginning of the conflict and one in a post-conflict Northern Ireland. Schwerter demonstrates how these works strive to avoid polarization and simplification. Instead, they present a significantly more nuanced and ← 3 | 4 → complex approach than the traditional cinematographic illustrations of Belfast during the Troubles.

Section Three foregrounds a selection of essays which explore the nature and impact of counter-discourses that represent challenges to powerful social institutions in Irish society. These include both the Church and the family.

The first paper, ‘Irish Dissenting Priests and the Renewal of the Church (Perhaps)’, examines the outputs of seven Irish priests, all of whom are well known for their hostility towards what they perceive to be an overly centralized and authoritarian institution. Maignant suggests that the arguments put forward in their publications in favour of inverting a top-down pattern of authority within the Catholic Church illustrate alternative ways in which an institution such as the Church could operate. In her view, they speak for many of those who have become alienated from the Church in more recent times.

Among the reasons for such alienation are emerging stories around institutional abuse, including clerical sexual abuse. Nathalie Sebbane in her paper ‘Counter Hegemonic Discourses on Institutional Abuse in Ireland’ focuses on children’s and women’s institutions including industrial schools, the Magdalene Laundries, and mother and baby homes. She then explores in depth the way in which new, challenging discourses of resistance, with their particular achievements and limitations, have developed in civil society, thanks in part to the use of social media.

Concluding this section, Duffy in ‘Emerging, Submerging Lesbians in Ireland’, draws on reflections of older lesbian women’s experiences of reaching an understanding of themselves and their identities. These ran counter to more mainstream identities with which they were surrounded while growing up, those of mother and carer within the family. Duffy describes how the participants in her qualitative study have experienced a society where the state institutions and the Church dominated mainstream discourse regarding sexuality. This paper charts the path taken by the women in creating a counter-discourse capable of embracing difference.

The fourth and final section of this volume is dedicated to ‘Provocation in Poetry and Performance’. Naugrette-Fournier in her contribution, ← 4 | 5 → ‘Resistance Days: From Dark Interiors of Resistance to The Disobedient Resistance of Raw Materials in Derek Mahon’s Poetry’, shows how the Northern poet advocates a new kind of non-violent resistance via the deconstruction of objects. This process is presented as necessary in order for new objects, energies and possibilities to emerge. The idea of a cycle of change is expanded to include the concept of replacing one society with another.

Carton-Charon’s ‘Christy Moore on Stage: Loss, Echoes and Movement’, probes the extent to which this singer and songwriter’s work encapsulates counter-discourses promoting countercultures. Despite being widely known as a folk singer, as this paper highlights, Moore’s songs have many features in common with other genres such as the protest song, in that they frequently call for another way of seeing the world and promote alternative perspectives to those which are more mainstream.

The volume concludes with Ó Liatháin’s ‘Dialogues des Morts: A Subversive Representation of Hades in an Eighteenth-Century Irish Manuscript’, which analyses the (mock) epic poem, ‘Eachtra Ghiolla an Amaráin’ (the adventures of a luckless fellow or ‘hostage to misfortune’), highlighting in doing so the subversive intentions of poet Donncha Rua Mac Conmara. In particular, Ó Liatháin considers his irreverent treatment of Virgil’s Aeneid and the use of role reversal to ‘turn the world on its head’, resulting in a counter-discourse around the position of the Irish language and the Irish people, as well as traditional literary hierarchies.

We are deeply grateful to all of our authors for their insightful contributions. Our hope for this volume is that it highlights the power and significance of counter-discourses in presenting other ways of thinking and being, and in stimulating reflection on the validity or otherwise of the unquestioned.

Subverting the Political Mainstream

Violent Irish Rebels versus Undercover Police Officers

Details

- Pages

- VIII, 258

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787077126

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787077133

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787077140

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781787077119

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11403

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (October)

- Keywords

- Non-violent resistance Counter-discourse Irish Studies

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2018. VIII, 266 pp., 1 fig. b/w, 2 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG