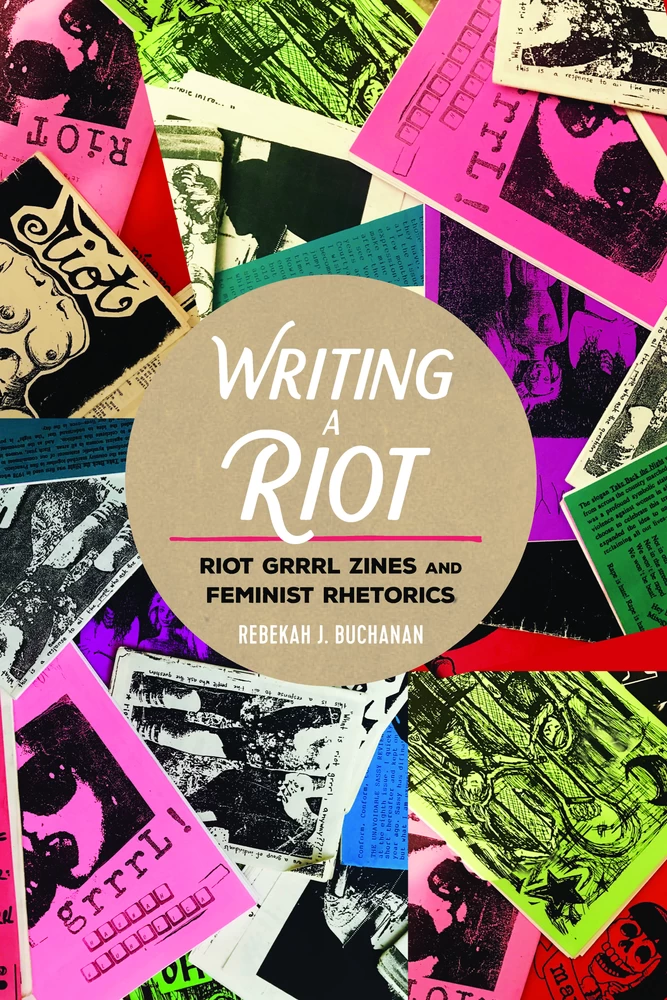

Writing a Riot

Riot Grrrl Zines and Feminist Rhetorics

Summary

In Writing a Riot: Riot Grrl Zines and Feminist Rhetorics, Buchanan argues that zines are a form of literacy participation used to document personal, social, and political values within punk. She examines zine studies as an academic field, how riot grrrls used zines to promote punk feminism, and the ways riot grrrl zines dealt with social justice issues of rape and race. Writing a Riot is the first full-length book that examines riot grrrl zines and their role in documenting feminist history.

“Focusing on the creation and circulation of riot grrrl zines in the 1990s, which she interprets as a complex literacy practice, Rebekah J. Buchanan adds substantially to the burgeoning literature on the challenge of narrating the history of punk feminisms. By building on her own experiences in zine-ing and reading with care and appreciation a diverse array of zines created during the period, she makes a strong case for the significance of such zines as evidence of girls’ feminism and activist efforts to understand the conditions of their everyday lives.” Janice Radway, Walter Dill Scott Professor of Communication Studies; Director, Gender Studies; Professor, American Studies, Northwestern University.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- Advance praise for Writing a Riot

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Why Place Matters: An Extremely Short Version of My Music and Feminist Histories

- Feminist Rhetorics and Zines

- Zines as Literacy Practice

- Bringing It All Together

- Part One. Zines and Punk

- Chapter 1. Girl Zine Studies

- Zines and Girls, Grrrls, Grrls

- Themes Around Life Writing

- Zines as Feminist Theory

- Zine Literacy Scholarship

- Librarian Zine Scholars and Archivists: Zine Histories’ Best Friends

- Conclusion: Why Zine Studies Is Needed

- Chapter 2. Putting the Riot Back Into Punk

- Contextualizing the Riot

- Complicating the Riot Grrrl Origin Story

- Situating Punk

- The Elements of Punk

- Punk in the Local

- Punk Feminists: Where Riot Grrrl Should Be

- Style as Substance

- Suffering as Commodity

- Shock Effect

- Concluding Riot Grrrls’ Position in Punk

- Part Two. Defining and Documenting Riot Grrrl

- Chapter 3. What Is Riot Grrrl Anyway?

- What Riot Grrrl Is to Me

- The Blackout and Its Aftermath

- Changing Riot Grrrl

- Boys or No Boys Allowed?

- Are We Any Different? Closing the Riot Grrrl Gap

- Chapter 4. Riot Grrrl Zines as Social Circulation

- Recording Feminist Herstories

- Media

- Experiencing the Body

- Learning About Zines

- Making Connections

- She’s in the Band

- Come to Our Prom

- Conclusions

- Part Three. Riot Grrrl Zines and Justice Issues

- Chapter 5. Yes, We Use the Word Rape

- Following the Footsteps

- Sexual Violence as a Social Problem

- Naming Names

- Supporting Friends

- Conclusions

- Chapter 6. Race and Riot Grrrl Zines

- The Context

- How We Talk About Privilege

- I’m Not a Racist, But…

- The One Drop Rule

- Discussing Race

- Conclusions: What to Do About Race?

- Conclusion. Who Cares? Or, Why Does Riot Grrrl Really Matter

- What Zine-ing Literacies Teach Us

- More Than a Movement: Origin Stories

- Index

- Series Index

When I started this project, I wasn’t sure of what I would find. As most scholars, I had an idea. I knew that zines are important. I also knew that how we document self and how we present and re-present history is constructed through various social, personal, and political constructs. Writing and representing zines can be difficult. There are so many variables. Trying to gather zines from 20 to 25 years ago is tricky. Zines are fleeting. Zine creators are sometimes difficult to find or identify. Names and addresses change. People stop writing zines and move on to write other things, get other jobs or vanish from the communities and scenes they were once so invested in. And, memory is tricky. The role of nostalgia and its place in memory can sometimes challenge the ways in which we think about our lives.

The zines I had access to came from three academic libraries or my personal collection. I tried to find writers and names and dates of zines. For some I was successful, for others I am still unsure of who wrote them or when they were published. There are accounts here that are incomplete, but in many ways, it is the very incompleteness that helps define the narratives and work of zines. Even if I know the last name of a zine creator, I used her first name to refer to her in order to keep how I referenced zine creators consistent. I have cobbled together dates and information from the zines and I believe that what ← xi | xii → I have created is accurate. I have, whenever possible, used the spelling and punctuation of zine writers, mistakes and all. If I have missed anything please forgive me. Or, better yet, inform me of what I’ve missed. But, remember, most of the information, especially names and dates, comes from the zines themselves—as long as they have them listed. I know I am missing zines and voices, but I tried to be as comprehensive as possible with the collections I read. I wanted to include as many zines and voices as I could find, yet some stories and voices may appear more often than others; such is the nature of gathering them in attempts to create a somewhat cohesive text. Some of the zines I’ve included are well-known in the zine community, and possibly outside of it. Many are probably long-forgotten except to those who wrote them.

My hope is that this book shows how riot grrrl zines are integral not only to creating communities but also to reconstructing narratives of music scenes during important historical time periods. In the spirit of zines, I also hope that this book helps to start conversations about zines and the role of zines in defining sites of resistance, as rhetorical sites, and as discourse communities. I am invested in representing zines and zine communities in a way that ensures these voices aren’t lost. I am invested in the ways in which we represent feminist scenes, punk (and other music) scenes, and how we talk about girlhood and the ways in which girls are represented and presented.

My fundamental belief about riot grrrl and riot grrrl zines is that these young women were, in many ways, just making it up as they went along. It’s a wonder that riot grrrls came together (and some may argue they never did) and the fact that they did speaks to how much young women wanted to be part of feminist, radical and activist communities. Was it perfect? No. Was it fundamentally different than other radical communities that came before it or have come after? No. Does any of that matter? Again, I would say no. Instead, I view zines and how they present riot grrrl as a way to better understand youth culture and examine how youth participate in creating culture in their local and national scenes.

There are some who argue that girls and women don’t appear in history books, text books, and cultural explorations because they didn’t participate in meaningful ways. This argument is able to continue and persist because we fail to acknowledge all the ways in which women and girls have participated in social, political, and personal change. We fail to view the ways in which women make change and participate in change as meaningful or important. In order to change this narrative, we need to continue to find and share the narratives and histories of women. We need to work to broaden our narratives, ← xii | xiii → doing what Krista Ratcliffe calls rhetorical listening, “siting with texts with the intent to understand not master discourses.”1

I want to make it clear that what I am presenting and critiquing is writing from specific moments in time. I am not arguing that the individuals who wrote these zines still believe what they did at 15 or would still write the same things if they had the chance to go back. I am also not arguing that they have changed or that what they wrote should be discounted because of their age. I know that people can change, and what I present here is not a judgment on the person; instead, it is a critique of the writing and rhetoric that is associated with the communities and scenes they were part of during the 1990s. I know there are ways in which people want to defend their writing (maybe what I am choosing to do here) as well as make sure the context is understood. Keep this in mind as you read. I have the advantage of time and age, but when I was 22 and graduating from my undergraduate institution in 1994, I might have had somewhat similar thoughts, and if you found my zines and writing, what I was doing could in some ways be similar. This does not mean it should not be examined and critiqued as such. Zines are, after all, created to be read and shared.

My hope is that in reading this book you learn more about how riot grrrl scenes were transformed and defined by the participants and not by the media or even those women viewed by most as the founders. I hope that if you have other zines or people who I should be reading or talking to about riot grrrl, you get in touch. I hope that if you were part of a scene, this book in some ways brings you back to the space. More than anything, my hope is that the words and beliefs of these young women and these zines are not lost. My hope is that these zines continue to create narratives and they tell the stories that are too often lost in our histories. Some would argue that most of these stories are the stories of the mundane and the everyday. I would argue that these are the stories that matter the most. They are the stories that continue to have an impact on how we have created important and instrumental sites of resistance.

Note

1. Krista Radcliffe, Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), 33. ← xiii | xiv →

I have to start by thanking all the riot grrrls who wrote zines. As I read through these zines, there were times I forgot where I was. Instead, I was back in my college illegally smoking cigarettes in my smoke free dorm, listening to Morrissey, and sitting on my bed reading zines. Thank you for being writers, for sharing your stories, and for being so open about your lives and experiences in your zines. I know that the zines I read are all over twenty years old, and many of you are not part of the zine community anymore, but please know that your words mattered.

Thank you to all the zine librarians and zine libraries. In particular, I could not have done this work without the Riot Grrrl Collection at NYU’s Fales Library, the Sarah and Jenn Wolfe Collection at The University of Iowa, and Barnard College Library. Thanks to Barnard’s zine librarian, Jenna Freedman, for all the wonderful work you do in collecting and cataloging zines. Thank you to the Popular Culture Association/American Culture Association for awarding me the Marshall Fishwick Travel Grant to Popular Culture Studies/American Culture Studies Research Collections and Western Illinois University’s Summer Stipend for grants that allowed me to visit these libraries and collections. ← xv | xvi →

Thank you to Joan Orr for handing me a stack of riot grrrl zines when I first came to WIU and you knew I did work on zines. Those zines were my first chance to really think about riot grrrl zines critically and the importance of them on zine-ing, feminist rhetorics, and punk scenes.

I have to thank the Punk Cultures Area at PCA/ACA for listening and debating parts of this throughout the process.

For the walks, runs, rants, Pub writing, encouragement, fox adventures and all-around amazing friendship I have to thank my own girl gang who helped me through all of this and let me bounce ideas off them even when they probably didn’t have a clue as to what I was going on about. Thank you Barb Lawhorn and Erin Taylor.

Finally, thank you to Jack and Lucy for giving me space to write but making me take time out to play games and watch YouTube videos. I will love you both forever. And to Chris, my King Neptune, who read through this too many times, filtered through my ideas when they were still percolating, and will always debate punk with me, all my love.

I’m writing this in 2017. Here in the United States, we’ve elected a president who has been recorded as saying because he is rich, he can “grab ‘em by the pussy.” We have congressmen who are wondering why men need to pay for prenatal care.1 A few months ago, I participated, along with millions of people around the world, in one of the many Women’s Marches. For the first time in my life, it seems that Roe v. Wade, the federal law legalizing abortion, has a real chance of being overturned. Feminism continues to be an offensive word and concept that is misunderstood and attacked. I’m not sure if the women who participated in what is now labeled as Third Wave Feminism over a quarter of a century ago believed that what they were doing would still need to be done today. Yet, the battle continues to be fought.

Why do we need a book dedicated to grassroots scenes grounded in punk and feminism? Why does documenting the history and narrative of riot grrrls matter? Sure, they are mentioned in articles, popular magazines, and music history, but why do they matter in literacy studies? There have already been books on riot grrrls as a music-based movement, most recently the work of Sara Marcus in Girls to the Front. I hope to make it clear that what the young women who were involved in riot grrrl did in the 1990s still matters. Their writings document feminist, activist, and youth histories that should not be ← xvii | xviii → lost. They represent narratives that in many ways helped to define ways in which youth talk about resistance during a time of cultural backlash against feminism. The scene has spawned “every girl is a riot grrrl,” “fight like a girl,” and encouraged the images of angry young women that are relevant in today’s political and social climate. They emphasize the reasons why we need Title IX, rape laws, abortion rights, and women’s right to choose. And their writing highlights savvy ways young women found to communicate with one another and share their stories.

This book is a long time coming. It brings together histories for me from when I was in college in the early 1990s, and even high school in the Reagan Era of the1980s. It is grounded in my scholarly interests, but is also a reflection of who I was during the time that these zines were written and how reading and rereading them brought me back to being a young woman during this timeframe. It is a way for me to navigate how activism was defined and redefined for me and other women born in the 1970s and raised in the 1980s. It is also a way to think about punk and the role of punk in historical contexts. Last summer I was in London and attended a number of events celebrating 40 years of punk, listening to people even older than me talking about how valuable being punk was (and still is) in defining their lives for the past 40 years.

Because of the various personal relationships I have with zines and punk, I have grounded this book in my personal history of how punk has impacted my experiences reading riot grrrl zines and the ways in which I value them as texts and memory work. As a feminist scholar, situating myself in the reading of the texts, the choices I have made in what texts to read, and the limitations of what I have laid out, are as important to my work as the actual zines themselves. Therefore, I start with my relationship to zines and punk and my biases toward why riot grrrl zines matter. I then situate my work in scholarship around zines and my approach to the work as a feminist rhetorical and cultural studies scholar.

Details

- Pages

- XXXVI, 182

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433123917

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433150784

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433150791

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433150807

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433150777

- DOI

- 10.3726/b12472

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (October)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XXXVI, 182 pp., 3 b/w ills.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG