The Cursus Enigma

Prehistoric Cattle and Cursus Alignments

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

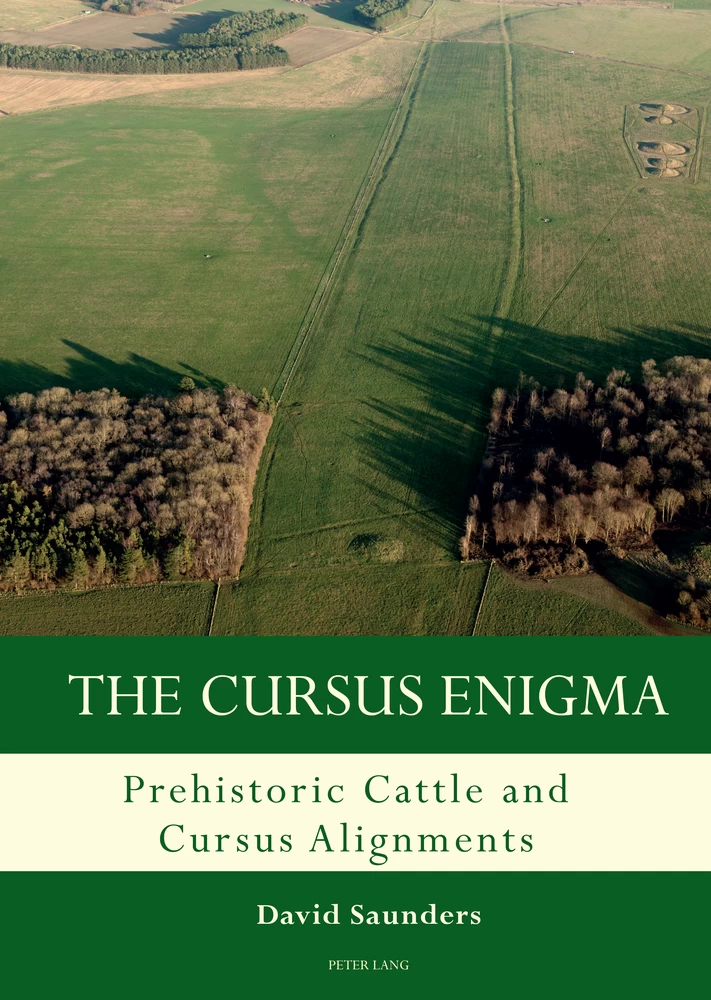

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Maps

- Foreword

- Preface

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Background

- Chapter 2 The Openness of the Landscape during the Mesolithic/Neolithic Transition Period 25

- Chapter 3 Geology, Geography and Topography

- Chapter 4 The Link with Hunting or Herding

- Chapter 5 Field Research

- Chapter 6 Cursus Monuments: A Statistical Evaluation

- Chapter 7 A Statistical Evaluation of my Fieldwork

- Chapter 8 A Case Study: The Milfield Basin

- Conclusion

- Appendices

- Appendix A Domestic Cattle Fauna Records from Locations Adjacent to Cursus Monuments

- Appendix B Identified Causeways in Cursus Monuments

- Appendix C Cursus Monuments Associated with Control of Cattle Movement

- Appendix D1 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Construction Dates

- Appendix D2 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Classification of Cursus Monument

- Appendix D3 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Terminal Types

- Appendix D4 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Straightness of Cursus Monument Ditches

- Appendix D5 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Geology

- Appendix D6 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Association with Rivers and Streams

- Appendix D7 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Alignment

- Appendix D8 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Celestial Alignment

- Appendix D9 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Neolithic Arrowheads

- Appendix D10 Mesolithic Finds in the Vicinity of Cursus Monuments

- Appendix D11 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Openness of Landscape

- Appendix D12 Summary of Cursus Monuments – Associated with River, Floodplain or Mist

- Appendix E Location of Aurochs’ Bones with Respect to Cursus Monuments

- Appendix F Cursus Monument Aerial Photography and Excavation Records

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series Index

Figure 1 Sulphur and carbon isotopic results from fauna within the Coneybury Anomaly

Figure 2 Yellow gravel deposit on southern mini-henge bank – Marden

Figure 3 Results of δ13C from Blick Mead

Figure 4 Ivinghoe Beacon in-site raw resistivity

Figure 5 Cambridge Archaeological Unit’s drawing of the Wolverton Cursus complex

Figure 6 Cursus monument alignment with other aspects within the landscape

Figure 7 Cursus monument alignment with celestial events

Figure 8 Direction of seasonal equinox at Stonehenge

Figure 9 Cursus monument association with rivers and streams

Figure 10 Comparison of statistic of previous cursus monument function theories

Figure 11 Cursus monument alignment with topography of landscape

Figure 12 Riparian zone alongside palaeochannel at Wolverton Cursus complex

Figure 13 Springline encouraging additional grass growth (Wolverton Cursus)

Figure 14 Cursus monument association with cattle husbandry

Figure 15 Cattle in mist at western terminal of Stonehenge Greater Cursus

Figure 16 Comparison of my theories versus previous theories

Table 1 Scottish timber cursus monument construction dates

Table 2 English cursus monument construction dates

Table 3 Cattle bone from cursus monument sites

Table 4 Cursus monument location identification scheme

Table 5 Neolithic arrowheads found at cursus monument sites suggesting hunting continues

Map 1 Summary of vegetation environment regions

Map 2 Distribution of washlands

Map 3 Distribution of cursus monuments within the study group

Map 4 Cattle movement across the Rudston Cursus complex

Map 5 Cattle movement across the Fimber Cursus

Map 6 Bag Enderby pit alignment HER number PRN 45338 – Crown copyright 1905

Map 7 Harlaxton pit alignment HER number PRN 33382 – Crown copyright 1905

Map 8 Cattle movement across Harlaxton pit alignment

Map 9 Inchbare North and South pit alignments

Map 10 Stenigot pit alignment HER number PRN 44857 – Crown copyright 1905

Map 11 Cattle movement across the Fornham All Saints Cursus

Map 12 Cattle movement across the Stratford St Mary Cursus

Map 13 Cattle movement across the Barnack, Maxey & Etton Cursuses

Map 14 Cattle movement across the Godmanchester & Brampton Cursuses

Map 15 Cattle movement across the Springfield Cursus

Map 16 The Stanwell Cursus complex

Map 17 Cattle movement across the Stanwell Cursus complex

Map 18 Cattle movement across the Biggleswade Cursus

Map 19 Cattle movement across the Ivinghoe Beacon Cursus

Map 20 Cattle movement across the Wolverton Cursus complex

Map 21 Cattle movement across the Benson Cursus

Map 22 Cattle movement across the Drayton St Leonard & Stadhampton Cursuses

Map 23 Cattle movement across the Drayton North & South Cursuses

Map 24 Cattle movement across the North Stoke & South Stoke Cursuses

Map 25 Cattle movement across the Sonning Cursus

Map 26 Stonehenge Bottom Ordnance Survey map of 1850

Map 27 Cattle movement across the Stonehenge Greater Cursus

Map 28 1811–1817 Historical map of Salisbury and the Plain

Map 29 Cattle movement across the Stonehenge Lesser Cursus

Map 30 Cattle movement across the Yatesbury (Avebury) Cursus

Map 31 Cattle movement across the Dorset Cursus

Map 32 Waddington’s interpretation of processional routes across the Milfield Plain

In the 100th edition of Current Archaeology magazine, a reader’s letter was published that pleaded for help in providing a definition for the term ‘cursus monument’. ‘I would be most grateful if you could inform me precisely what is meant by a “cursus”’ wrote Norah Leggett. She stressed that she had been unable to find out what a cursus monument was, even in an archaeological dictionary. In the forty years or so since this plaintive letter was written, archaeologists have made periodic efforts to answer this question, with mixed success. From time to time a piece of research comes along that makes a fascinating contribution to this discussion, and David Saunders’ book contains just such a piece of research.

This kind of research is needed, because these large to enormous earthwork and timber post-defined enclosures of fourth millennium BC date may have dominated the lives and landscape of the first farmers in Britain, but cursus monuments have made substantially less impact on the pages of archaeological textbooks. Cursus are the kind of site that generally get a contractual obligation paragraph or two in synthesis of the Neolithic period, and prehistory, of Britain, a trend that goes back to Stuart Piggott’s 1954 book The Neolithic Cultures of the British Isles. This paragraph is usually an apologetic interpretative shrug of the shoulders that concludes with the supposition that these were monuments of a ceremonial nature, probably involving processions, but what else is there to say?

The book that you hold in your hands is a rare example of a detailed, data-driven study that has as its central focus cursus monuments. Works of a similar depth have been few and far between, with notable exceptions being book-length contributions to solving the ‘cursus enigma’ or ‘cursus problem’ written by Roy Loveday (Inscribed across the Landscape, 2006) and myself (Reading between the Lines, 2015). Alongside an edited volume (Pathways and Ceremonies, edited by Barclay and Harding in 1999), a few major fieldwork projects, both research and developer-funded, have focused on a cursus-dominated place, from Drayton in Oxfordshire to the Cleaven Dyke in Perth and Kinross. Yet such studies do not afford the space to think or the words to express a detailed exploration of the cursus monument as either a prehistoric tradition or a curious archaeological piece of terminology.

David Saunders in this book presents an innovative, fascinating, provocative and intriguing answer to Norah Leggett’s question. That is not to say that this is the definitive account, or that David has solved the cursus problem. Neolithic monuments tend to fall into roughly coherent typological groupings that we then burden with obscure and problematic names: cursus, henge, palisaded enclosure and so on. Yet these classifications often impose an artificial uniformity in terms of what the function of such monuments might have been within Neolithic society. Yet it is likely that enclosures served various different roles and purposes even to those who built, and used them, and that meaning may have changed from generation to generation.

The meaning of cursus monuments to us, archaeologists, has also changed from generation to generation, and David’s ideas presented in this book offers a cursus theory for our time, when there is more concern than ever with thinking about the Mesolithic inheritance (as Denise Telford once put it) that influenced Neolithic farmers. By considering cursus monuments in terms of landscape, hunting practices and animal husbandry, we can start to consider how these enormous monuments cut across a range of aspects of the lives of those who built, used and encountered them, as opposed to fuzzy ritualistic roles. We may never truly know what cursus monuments were, but this book moves us one further step along the journey to achieving the goal of satisfying the curiosity of one Norah Leggett.

Kenneth Brophy, March 2020

Many have struggled to understand the reason behind the construction of cursus monuments and their possible purpose, which has led to them being often described as ‘enigmatic’. Previous cursus monument studies have tended to focus on the construction or post-construction phases of the monument, rather than upon the reason a Neolithic community decided to locate and align these monuments where they did. Perhaps, at this current time, the sole use of an archaeological methodology has gone as far as it can with regard to explaining the ‘cursus enigma’. This book takes a new approach to the cursus monument debate by incorporating a fresh methodology, previously unexplored in cursus monument investigation. It looks to combine previous archaeological methodologies with an understanding of the different styles of movement of various large herbivores, to identify whether any correlation exists between the initial placement and alignment of Neolithic cursus monuments and these types of movement. This has enabled the study to identify a strong correlation between the placement and alignment of Neolithic cursus monuments and the movement of domestic cattle within that landscape, thus making an original contribution to the cursus monument debate.

Growing up in West Sussex, living less than 50 m from the rivers, floodplains and meadows of the Pulborough Brooks, my early memories are of wandering those pastures, moving through fields of cattle with fishing rod in hand, the herds often coming within a few feet, sometimes less, as they tried to discover what I was up to. Little did I know that those childhood experiences of long summers spent interacting with cattle would play such an important role in my future archaeological career.

David Saunders

The research outlined in this book has identified a strong correlation between the movement of domestic cattle and the placement and alignment of Neolithic cursus monuments, thereby making an original contribution to the cursus monument debate. The possible correlation between these monuments and the movement of Neolithic pastoralist communities within the landscape had not been well explored in previous research. Previous cursus monument studies have tended to focus on the construction or post-construction phases of the monument, rather than on the reason a Neolithic community decided to locate and align the monuments where they did. The study on which this book is based used quantifiable data gathered through the fitting of GPS collars to American range cattle (George et al. 2007) to determine the terrain over which cattle move. This was combined with GIS elevation and slope data from a GIS software programme supplied by Environmental Systems Research Institute.

This enabled a quantifiable examination of fifty cursus monument sites on or adjacent to the English chalkland belt to determine the movement of cattle across the landscape at each individual monument site. Investigation into areas of natural restriction to the landscape and areas affected by winter flooding of pasture enabled the identification of areas that could have aided cattle movement and husbandry at prime points during the early spring. The inclusion of boots-on-the-ground field observations across each of the fifty monument sites has helped overcome issues associated with previous studies, where results from a few ideal examples appear to have then been extrapolated to the rest.

The linking of cattle movement data to mainstream archaeological research identified that cursus monument sites appear to align with the potential routes of domestic cattle across the valley profile. Further investigation into areas affected by the winter flooding of pasture identified a strong correlation with the precise location of cursus monument sites.

The study suggests that cursus monuments commenced life as droveways, perhaps identifying an initial practical function to the landscape prior to any possible later ritual importance of the sites. A case study was undertaken to re-evaluate these ideas using research undertaken in the Milfield Basin in Northumberland, an area that appears to have had a droveway which did not develop into a cursus monument.

I would like to thank the following people and establishments: David Jacques of the University of Buckingham for his enthusiasm and support throughout this process and for use of material relating to the Blick Mead site; The University of Buckingham, the University of Durham, the University of York and the University of Reading for the opportunity to analyse potential large herbivore movement throughout the Stonehenge landscape by making available their research undertaken at Blick Mead; Peter Rowley-Conwy and Bryony Rogers of the University of Durham for the opportunity to analyse potential aurochs movement throughout the Stonehenge landscape by making available their research on isotopic data undertaken from two aurochs’ teeth discovered at Blick Mead.

I am especially grateful to the following people: Graeme Davis and Nick James for their continued support both during and after their supervision of my studies in Archaeology; Tim Darvill of the University of Bournemouth for his support and encouragement throughout this process and for his kind permission to critically dissect the cursus monument definition within his 2008 publication of The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology; Peter Rowley-Conwy of The University of Durham for giving me access to his chapter ‘To the Upper Lake: Star Carr revisited – by birchbark canoe’ as one of the fifty offprints within his latest book Economic Zooarchaeology; Chris Green of Oxford University for his explanation on the use of mass modelling data undertaken as part of the English Landscape and Identities (EngLaId) project and how to incorporate his research within the Mesolithic/Neolithic transition period; Steve Marshall for his extensive guidance with regards to the spring networks surrounding the Avebury monuments: Richard Crook, of Vineys Farm, Amesbury, a local farmer with fifty years’ experience farming in the Stonehenge landscape, for explaining why cattle appear to relish eating grass within mist-filled valleys; and Mike Clarke, custodian of Blick Mead, Amesbury, for many hours discussing the countryside and country skill aspects of the Blick Mead area.

Details

- Pages

- XXVI, 222

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781789977455

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789977547

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789977554

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789977561

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16559

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (March)

- Keywords

- The cursus enigma Prehistoric cattle movement The alignment of cursus monuments The Cursus Enigma: Prehistoric Cattle and Cursus Alignments David John Saunders

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. XXVI, 222 pp., 7 b/w ill., 41 color ill., 6 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG