From Blackface to Black Twitter

Reflections on Black Humor, Race, Politics, & Gender

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

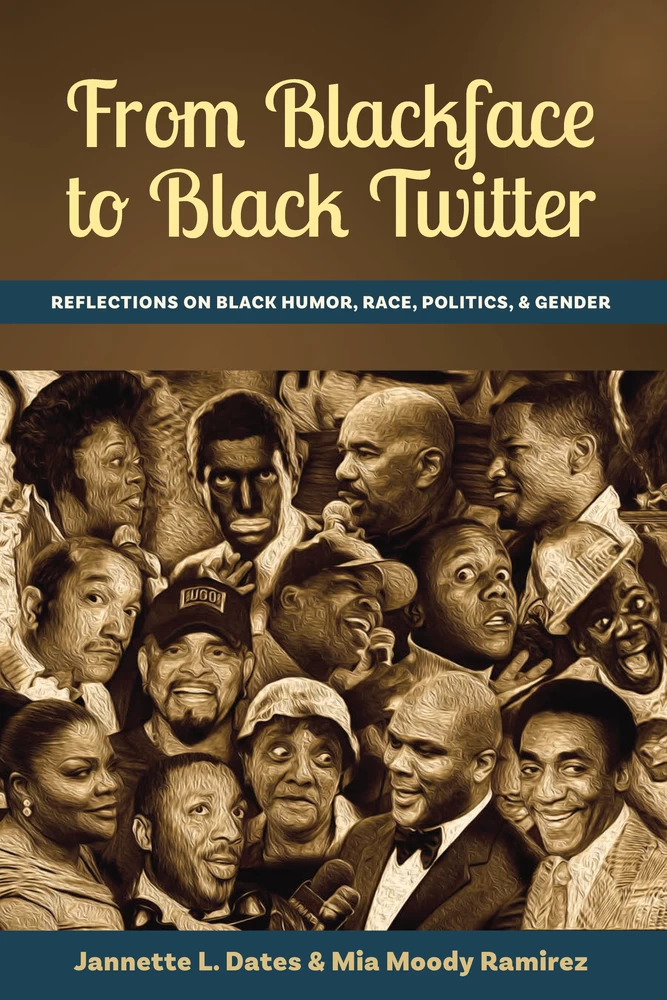

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- Advance Praise

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Methods of Exploration

- Note

- References

- Part I. The Roots of Black Humor

- Chapter 1. Overview, Structure, and Significance of Book

- Theoretical Framework

- Book’s Significance

- Overview of Chapters

- References

- Chapter 2. Pre-Slavery Through the 19th Century

- Defining Humor

- Hegemony, Humor, and Slave Narratives

- Discourse of Whiteness

- Minstrel Shows

- African American Men and Minstrelsy

- Jim Crow Humor

- Yankee-Doodle and “Coons”

- The Trickster

- Signification and the Signifying Monkey

- The Dozens

- Uncle Tom

- Rastus

- African American Women and Minstrelsy

- Mammy Stereotype

- Sapphire/Angry Black Woman

- The Jezebel

- The Tragic Mulatta/o

- Mixed-Race Males

- Notes

- References

- Part II. The Fruits of Black Humor

- Chapter 3. The Twentieth Century

- The Early Years

- The 1960s–1970s

- The 1970s

- Comedy Venues

- The Apollo

- The 1980s

- Interest Convergence and Comedy

- Eddie Murphy

- The 1990s

- The Birth of the Web

- Def Comedy Jam and Hbo

- Hbo

- Chris Tucker

- Chris Rock

- Ice Cube and the Friday Movies Legacy

- In Living Color: The Wayans Family

- The 2000s

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 4. Representations of Black Men and Kings of Comedy

- Kings of Comedy and Representations of Black Men

- Steve Harvey

- Cedric the Entertainer

- D. L. Hughley

- Bernie Mac

- Martin Lawrence

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 5. Black Feminism and the Queens of Comedy

- Intersectionality and Mass Media

- Note

- References

- Part III. Black Comedy, Social Identity, and User-Generated Content

- Chapter 6. 21st Century-Humor and Social Identity

- Notable Facts: 2000s

- Humor in the 21st Century

- Dave Chappelle

- Key & Peele

- The Comedy Get Down

- Child Rearing and Privilege

- Black-ish

- Social Movements

- References

- Chapter 7. Black Twitter, Social Movements, and Politics—Humor Across Media Platforms and Memes

- The Medium Is the Message

- Social Media

- Black Twitter

- Sharing Culture on Black Twitter

- Black Twitter and the Clapback Culture

- #StayMadAbby

- Twitter and the 2017 Removal of Omarosa Newman From the White House

- Vine Humor

- Andrew B. Bachelor aka King Bach

- D. C. Young Fly

- Jay Versace

- YouTube as a Platform

- References

- Chapter 8. Humor and Citizen-Produced Memes

- The Power of Memes

- The Online Transmission of Memes

- Bill Cosby-Inspired Memes

- #MeToo Campaign

- Memes and the Remake of Ghostbusters: Leslie Jones

- Rachel Dolezal-Inspired Memes

- #Blacklivesmatter

- Black Face and Tropic Thunder vs. Soul Man

- References

- Part IV. Black Humor and Politics

- Chapter 9. Humor and President Obama

- Memes and Social Media

- Facebook and Political Humor

- A Postracial Society?

- The Role of Humor in the 2016 Election

- Framing of Candidates in Humorous Memes

- Post-Election 2016

- Comedians Weigh In on the Election

- References

- Part V. The Future of Black Comedy

- Chapter 10. Conclusions and Focus on the Future for Black Comedy

- References

- Appendices

- Appendix A: Noteworthy African American Men in Comedy (Both Stand-Up and Screen)

- Appendix B: Noteworthy African American Women in Comedy (Both Stand-Up and Screen)

- Appendix C: Images Used in Cover Collage

- Index

We wish to acknowledge and thank everyone who contributed to the success of From Blackface to Black Twitter. Without you, this three-year project would not have come to fruition. We are most grateful for the patience and selflessness exhibited by our families as we spent hundreds of hours researching and writing this book. We appreciate the encouragement of friends, students, family and colleagues. We acknowledge and thank the institutions for which we have dedicated our academic careers—Howard and Baylor Universities. We thank former Baylor Journalism TA Wenjing Shi for her contributions to Appendix A and B. We also thank Baylor graduate student Andrew Church for the hard work he put into creating the cover for this text. We thank the editors and reviewers for offering feedback help on this project. In particular, we thank Dr. Meta G. Carstarphen for an early review of the book. Your suggestions and feedback were invaluable. Finally, we thank acquiring editor Kathryn Harrison for believing in us and Peter Lang Publishing for the opportunity to publish this work.

From Blackface to Black Twitter: Reflections on Black Humor, Race, Politics, & Gender traces the roots and fruits of comedy in the United States over the centuries to analyze and offer insights into the intersections of race, gender and politics in the humor developed by, for and, or about black people in the United States. The book’s ten chapters focus on how black and African American comedians of various periods used their communication skills and styles to reach professional and sometimes personal goals. We also analyze some of the obstacles they faced. We examine the ways in which race-related stereotypes and cultural narratives are often injected into humor by, for and about black people.

Further, we explore how African American humor has also reflected larger societal issues; frequently the humor was not designed just to make audiences laugh, but was written and delivered to also make them think differently about issues. We focus on common threads that can usually be discerned—that are found among black comedians across time, generations, genders and types of humor. We specifically address the uses of humor during pivotal points in history such as the enslavement years, the Jim Crow era, the civil rights movement era, and the period of the Black Lives Matter Movement.

Jesters, tricksters, humorists and comics have always been an integral part of African and then of African American life. Despite their bleak circumstances, ← 1 | 2 → America’s enslaved people and then its African American citizens who were dominated by Jim Crow laws and actions, used humor throughout as a means of teaching, framing, shaming, lecturing, child-rearing, ridiculing, tricking, maneuvering, manipulating and/or promoting various viewpoints. In fact, to keep from crying in despair, pain or anger, African Americans often used humor to more freely express ideas that were not allowed to take root or bear fruit in most other venues. Sometimes they could use humor to skillfully control or manipulate what most often was an otherwise hostile environment, as they quietly used rhetorical devices to achieve psychological satisfaction while avoiding direct confrontation. These devices allowed them to express ideas and opinions with encoded messages as they indirectly established their own views or sometimes their sense of dominance within what seemed to be innocuous verbal exchanges.

Most often, over the years each of the black humorists described in the following pages used their talent and skills to help move society toward more inclusion of their people. That was the implicit or explicit goal of many of their comic acts and the embedded messages they delivered to black and mixed audiences. We focus on this aspect of how these skilled communicators often worked to help uniquely and humorously “move the needle” toward greater acceptance and inclusion of differences between and among black people by their own people and by the larger society.

We begin with a reflection on the enslavement period. Tales about the signifying monkey that had permeated African cultures, over time became a part of African American folklore, as well. As described and interpreted by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in his seminal work The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African American Literary Criticism (1989, 2014), individuals transported the signifying monkey trope across the Atlantic by means of the dreaded “Middle Passage,” as the enslaved people who were brought to the new world used their recollections of and stories from their homelands about the signifying monkey. Gates noted that the signifying monkey trope appears among numerous nations where African people and/or their descendants lived and live today.

In the next section, we place the focus on the nation’s 20th century black entertainers, whose comedy was offered by, developed for and/or were about African Americans. We explore the various venues used to spark the careers of African American comedians, as we explain how from minstrelsy to vaudeville to the Chitlin Circuit* to the Apollo to Def Comedy Jam—the careers of black comedians were launched by means of various techniques and methods.1 ← 2 | 3 →

Next, we offer an introspective review and analysis of how, by the 21st century, American black comedy, black comedians and comedy about black people had evolved worldwide, as the methods of disseminating humorous messages shifted over the centuries, from the word of mouth of African tricksters to blackface comedy to on-stage performances to television comedies to user-generated content produced on the Web.

We focus attention on how, within the black community, by the 21st century communication evolved to include the user-generated content shared on social media sites, such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram in what scholars commonly refer to as “Black Twitter.” Twitter, which turned 11 years old in 2017, changed how people communicated and was especially significant for black users. The segment of the population, collectively known as Black Twitter, used the platform to “clapback” (giving appropriate, sharp tongued answers to negative messages from others) at social injustices and to drive visibility to discussions about black life and culture, led by those who knew it best: black people (Workneh, 2016). Popular clapback hashtags included: #Oscarssowhite, #blackgirlmagic., #StayMadAbby, #NiggerNavy, #ThanksgivingClapback and #YouOKSis.

In the 21st century, comedians and ordinary U.S. citizens, alike, use socio-cultural devices, and social media platforms, such as Twitter, to disseminate humorous messages about various matters—from politics to social movements to racism. Within the following pages, we highlight how the Web now offers a platform for many who wish to share humorous yet insightful messages that explore important, innovative topics such as social justice issues, women’s rights concerns, politics, President Barack Obama’s two terms in office, and the period leading up to and the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election as the 45th president of the United States.

We compare, contrast and question, in each of the periods, key differences and similarities in comedians’ styles, communication strategies and the platforms they used for disseminating their humor. We also examine ways in which people inject stereotypes and cultural narratives into African American humor. We tease out the distinctive features of black humor, built—for the most part—around the desire of each comedian to reveal who they were and how they viewed the world as they told their own and other people’s stories. We share perceptions about these “humor experts,” who sometimes helped to expose perceived racism and embraced or explained “racial identity” issues, and racial issues, while others among them skillfully avoided doing so. ← 3 | 4 →

To examine these important topics, we make use of cultural studies and critical media studies; at these studies’ core is a concern and a critique of the configuration of culture and society where the scholars’ sights fix firmly on social transformation (McQuail, 2002). Critical media studies view discourse as interactions between producers and audiences. In the process of studying a problem, the researcher acknowledges his or her own bias and position on the issue; this is known as reflexivity.

Critical media scholars use a meta-theoretical model that combines critical social theory, philosophy, media, communications studies and other disciplines, along with cultural analysis to look at modern media systems and studies, such as the Web, discourse analysis and cultural studies. The three-part approach to media studies often addresses ideology, context, and audience reception, where ideology is important because most dominant ideologies serve to reproduce social relations of domination and subordination.

Within the context of cultural studies and critical media studies, From Blackface to Black Twitter approaches the review and examination of humor in two ways: 1) we review existing literature on the topic of African American humor, showing how comedy has been used by, for and about people in the black community as well as by others for various purposes and as expressed in other communities, and 2) we use discourse analysis and Critical Race Theory (CRT) to examine various texts, including comedy sketches, audios, films, TV shows, videos, and user-generated content (found on the Internet).

With an emphasis on gender, race and politics, we begin with brief analyses of various eras in U.S. history, offering a glimpse at how the comedy art form grew and continued to evolve and broadly influence popular culture. Our work extends the important literature already focused on this topic by examining how, in 21st century American culture, politics and political movements—black/African American comedy continues to play unique roles.

Comedy in film, social media, TV, advertising and other platforms reproduces dominant forms of social power whether based on race, gender, class. economics or their various contributions. Accordingly, the chapters in this text demonstrate how humor is an integral part of America’s political and social/cultural struggles and why humor by, for and about black people is often about the skillful uses of survival strategies in a hostile world. We explore some comedians’ unique communication goals and techniques and compare ← 4 | 5 → theirs to other comedians of their day. We focus most on the period from 1990 into the 21st century.

CRT studies seek to travel beneath the surface and help researchers outline culture as a narrative in which texts consciously or unconsciously link themselves to larger stories at play in society. Such analyses often look at how cultural meanings convey specific ideologies of gender, race, class and other dimensions. Scholars studying marginalized groups gravitate to interpretive methods because such methods offer insights into often submerged complexities in society (Bogdan & Biklen, 1982). Inserting texts into the system of culture within which media produce and distribute ideologies can help explain and clarify features of the texts that content analysis alone might miss or downplay.

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 200

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433154546

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433154560

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433154577

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433154584

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433154553

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13336

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (August)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XVIII, 200 pp., 3 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG