Non-Violent Resistance

Irreverence in Irish Culture

Summary

This volume investigates the many ways in which writers, playwrights, politicians, historians, filmmakers, artists and activists have used irreverence and humour to look at aspects of Irish culture and explore the contradictions and shortcomings of the society in which they live.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction: Humour and Irreverence as Subversive Weapons in Irish Culture (Agnès Maillot)

- Part I: Satire in the Media

- 1 From Belfast to Jerusalem via Rio de Janeiro: Imaginary Geographies and Anti-Imperialism in Carlos Latuff ’s Political Cartoons (Marie-Violaine Louvet)

- From Rio de Janeiro to Belfast: Latu and Imaginary Geographies

- Sympathy for Irish Nationalists and Republicans

- Republicans and Palestine

- Latuff’s Collaboration with Irish Pro-Palestinian Associations

- Irish Ship to Gaza

- Latuff’s Subversive Views

- Conclusion

- 2 ‘The Long and the Short of it All’: De Valera, Seán T. O’Kelly and Dublin Opinion (Felix Larkin)

- 3 Humour, Satire & Counter-Discourse around Ireland’s 2015 Marriage Referendum Online: An Analysis of #marref (Dónal Mulligan)

- Twitter, Political Discourse, and the Case of Ireland

- #marref: The 2015 Marriage Referendum Discourse

- Methodology

- Satire, Parody, and Humour in the #marref Discourse

- Examples of Highly-Shared Satirical and Parodic Content

- Conclusions

- Part II: An Alternative Ulster

- 4 Rather Sex than Pistols: Good Vibrations and the Punk Scene in Northern Ireland (Agnès Maillot)

- Northern Ireland Punk

- Good Vibrations as a Comedy of (Ill) Manners

- 5 Just Books: An Alternative Bookstore in Belfast (Fabrice Mourlon)

- Alternative Research Practices?

- Just Books, an Alternative Bookshop in Belfast

- Conclusion

- 6 Seán Hillen’s Troubles: A Long-Censored Satire of the Conflict (Valérie Morisson)

- Disjointing the Real

- A Critical De-Realisation of the Conict

- Vilied Irreverence: Satire and Dissent

- 7 ‘A Remnant in the Land’: The Ulster Scot, Writing and Resistance (Wesley Hutchinson)

- Religion and Resistance: The Example of Alexander Peden

- Economic and Social Resistance

- Political Resistance

- Conclusion

- Part III: Parody and Irreverence in Irish Literature

- 8 ‘Bringing the Big House Down’: Molly Keane and the Tradition of Irish Satire (Sylvie Mikowski)

- 9 From Ireland, with Irreverence: The ‘Fierce Indignation’ of Jonathan Swift and Paul Durcan (Anne Goarzin)

- A Network of Evidence: Sick Bodies, Sick Solutions

- What Bodies Stand For: Important Matters

- 10 Deconstructing and Reconstructing Irish Folklore: The Irreverent Parody of An Béal Bocht (Vito Carrassi)

- Folklore and Authenticity

- Flann O’Brien and Irish folklore

- Chapter 4 of An Béal Bocht

- Between Deconstruction and Reconstruction

- 11 Seán Ó Faoláin and De Valera’s ‘Dreary Eden’ (François Sablayrolles)

- Writing as Resistance: An Embittered Young Man Doing Battle with the Censor

- Ó Faoláin’s Interest in History and Theses

- Splitting the Critics: Trenchant Reactions to Ó Faoláin’s Work

- Resistance through the ‘Discourse “of” the Method’

- Conclusion

- Part IV: Performing Irreverence

- 12 Once more with Feeling: Restaging History in the Work of Gerald MacNamara (Eugene Mcnulty)

- Joking Aside

- Play It Again Suzanne

- 13 Mr Emmet will never have an Epitaph: Brian Friel’s The Mundy Scheme (Maria Gaviña Costero)

- The Island of Eternal Rest

- The Play’s Universality

- 14 Violence and the Catharsis of Beyond the Grave Counter-Discourse in the Theatre of Brian Friel (Virginie Roche-Tiengo)

- Manuscripts Consulted

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Series index

Introduction: Humour and Irreverence as Subversive Weapons in Irish Culture

In January 2015, a proposed Channel 4 sitcom on the Irish famine sparked widespread controversy, with Tim Pat Coogan pointing to the ‘unsavoury’ nature of such a project.1 Within days, a petition circulating on the internet gathered more than 30,000 signatures, and a handful of protesters picketed Channel 4’s headquarters in London with banners reading ‘Mass murder is not comedy’.2 The outcry focussed on the offensiveness of the underlying concept. But was it offensive? Decidedly not, accordingly to Diarmuid Ferriter, who reminded the Irish Times readership that this had definitely been done in the past, not least by Jonathan Swift in his notorious A Modest Proposal, where humour served an essential function.3 The controversy over the proposed series, which Channel 4 eventually decided not to produce,4 raised interesting questions about the role that humour, by its very nature controversial, plays in social interaction but also about its power to question and challenge assumptions, thus becoming a weapon of subversion. Its meaning and interpretation are complex and embedded in the culture that generates them. In order to understand laughter, as French philosopher Henri Bergson wrote, ‘we must put it back into its natural environment, which is society, and above all we must determine the utility of its function, ← 1 | 2 → which is a social one. Laughter must answer to certain requirements of life in common. It must have a social signification’.5

The scrutiny of Irish culture through the lens of humour is fundamental, as it contributes to an alternative reading of events, albeit an irreverent and controversial one. As John Updike wrote of Sally Mara’s, AKA Raymond Queneau’s, witty re-imagining of the Easter Rising, humour can for instance bring ‘casual ambivalence’ to the fore.

This volume explores the many ways in which writers, playwrights, politicians, historians, filmmakers, artists, and activists have used irreverence and humour to look at aspects of Irish culture, and have succeeded in showing the contradictions and the shortcomings of the society in which they live.

The first part of this book looks at the role played by satire in the media, on many different levels and through an array of tools, be they caricatures, cartoons or digital media. Starting this section is Marie-Violaine Louvet’s ‘From Belfast to Jerusalem via Rio de Janeiro: Imaginary Geographies and Anti-Imperialism in Carlos Latuff’s Political Cartoons’, which analyses the anti-imperialist pictorial discourse that this Brazilian cartoonist uses to comment on the political situations in Palestine and in Northern Ireland, through the use of symbols, references, and historical milestones. Latuff has painted a number of murals in Belfast and Derry, more often than not to express solidarity with political prisoners in Ireland and Palestine. Quite interestingly, he has published cartoons which criticised the current line taken by Sinn Féin and undermined Martin McGuinness, then Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland. Some of his cartoons seem to advocate armed resistance not only in Palestine, but also in Ireland. This article highlights his use of satire to connect the Irish myth of resistance to British imperialism with that of Palestinian resistance to Israel, as well as his subversive position as a hard-line political cartoonist.

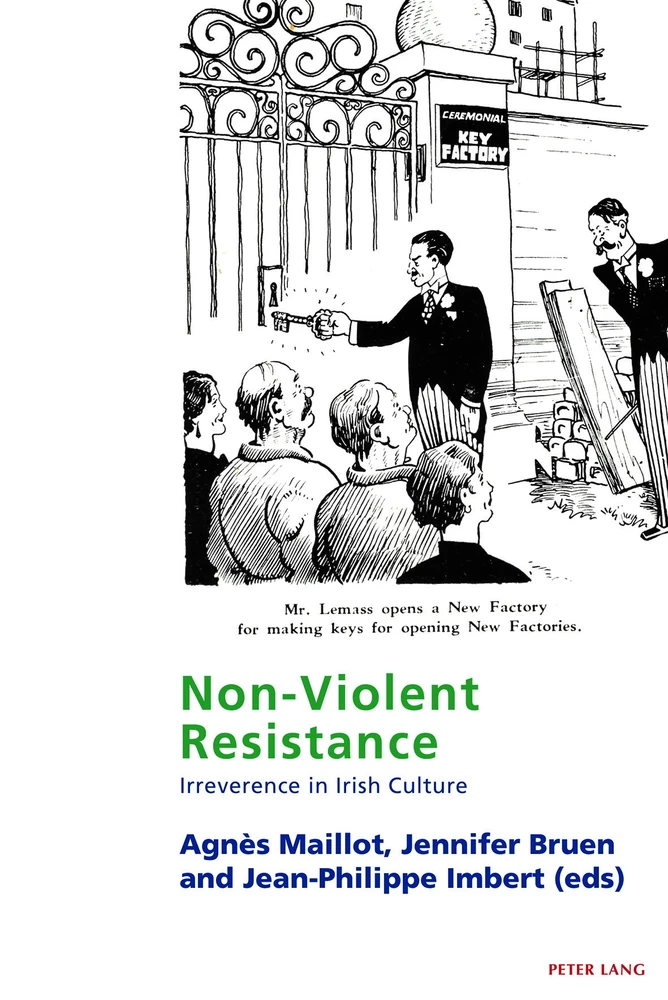

Felix Larkin then examines how Dublin Opinion, the self-styled ‘national humorous journal of Ireland’, fits comfortably into what the late Professor Vivian Mercier has called the ‘Irish comic tradition’. Published ← 2 | 3 → monthly between 1922 and 1968, it was a miscellany of quips, short articles, poems, and cartoons – all in a humorous vein, but with serious intent. The journal, without sacrificing its humour, had the capacity to convey a serious message – and the message had greater impact because it was delivered in a humorous way. More generally, however, its editorial team saw humour as an inherently serious matter. This chapter outlines the history of the journal over its forty-six years of continuous publication, with special focus on the role it played in 1959 in defeating Éamon de Valera’s attempt to abolish the proportional representation system of voting in Ireland. The referendum necessary to effect the change was lost by a narrow margin – less than 4 per cent – and two memorable cartoons in Dublin Opinion are credited with turning public opinion against the proposal. Arguably, that was the journal’s finest hour.

In the last chapter of this section, Dónal Mulligan analyses the extent to which satire and irreverence from activists on either side entered the online discourse around Ireland’s 2015 Marriage Referendum. ‘Humour, Satire and Counter-Discourse Around Ireland’s 2015 Marriage Referendum Online: An Analysis of #marref’ focuses on the mediated conversation space of Twitter, to identify patterns of interaction and influence in order to assess the role of humour in advancing and reacting to the discourse around this social change. This research uncovers patterns of communication, interaction, reciprocity and influence during the extensive period leading up to the vote, during the process and count, and in the aftermath of the result. It thus contributes to our knowledge of the mediation of political action and discourse around change-making broadly, as well as of the specific nature of the online discourse and counter-discourse around this historic event in Ireland.

The next section of this book deals with Northern Ireland. While it is not often that humour is used as a discursive tool or even as a strategy to delve into the darkest aspects of the conflict, all four papers show the impact that irreverence can have on changing perspectives on and approaches to violence and division, and how it has been used as a mechanism to counter the mainstream discourse and analysis of the conflict.

In ‘Rather Sex than Pistols: Good Vibrations and the Punk Scene in Northern Ireland’, Agnès Maillot revisits an episode of the conflict which has recently been of much interest to music lovers and academics alike, ← 3 | 4 → that of the punk scene in Northern Ireland. Good Vibrations (Lisa Barros D’Santos and Glenn Leyburn, 2013) is the account of those alternative years seen through the biopic of Terri Hooley, ‘Belfast’s chaotic godfather of punk’.6 Through the meandering life of its main character, the film depicts with humour and sometimes bleak sarcasm the darkest aspects of the conflict, in contrast with the potential that punk offered, for a short period of time, to unite, to uncover talents, to enable working-class disaffected youths to come out of their ghettos. This chapter shows how sectarianism, civil strife and missed opportunities were temporarily set aside when punk, through the character of Terri Hooley, became the irreverent and hopeful voice of the first generation of teenagers who grew up with the conflict.

During the same period, the anarchist collective and their flagship bookshop Just Books located in the same building as Terri Hooley’s record shop were thriving. Fabrice Mourlon, in ‘Counter-Discourses during the Conflict in Northern Ireland: The Case of Just Books, an Alternative Bookstore in Belfast’, examines how the post-Good Friday Agreement period has opened up spaces for alternative discourses and practices that developed during the conflict. Mourlon looks back at the dynamics of the anarchist movement in Belfast by focussing on the activities of Just Books, a bookstore that became a hub for minority groups that wanted to challenge dominant politics from 1978 to 1994. Relying on the testimonies of the people who founded the bookstore and who are still active in reviving it (Just Books was re-opened in April 2016), this research represents a co-construction of a narrative between the researcher and the object of his research and shows the power of a discourse which was entirely at odds with its surroundings and which aimed at subverting the main political narrative of the conflict.

The third chapter in this section is dedicated to Seán Hillen’s work. While Irelantis and the subsequent series of images have become extraordin-arily popular, the Troubles photomontages have never been truly accepted on account of their sharp attack on war-related violence and Irish sectarianism. Nevertheless, they are as comical as the Irelantis series but much more irreverent and satirical. 4 Ideas for a New Town (1982), Jesus Appears in Newry (1991–1992), Londonnewry, A Mythical Town (1983–1992), Northern Sunsets, and Newry Gagarin (1992) are sets of photomontages in a postcard ← 4 | 5 → format which mix black and white photographs of the Troubles, popular images related to American movies or the space Odyssey, kitsch icons of Jesus, and romantic Irish landscapes. Valérie Morisson’s article thus shows how Hillen, a fine postmodern satirist, offers a provocative interpretation of the conflict by pasting together real and fictitious, serious and comical, Irish and English or American images. Though the hybrid scenes which he composes play on the utopian genre that is dear to him and are irresistibly humorous, they convey a fierce criticism of the Northern Irish conflict and its representations. His montages castigate the dramatization of violence in the mass media but they also mock Catholic icons by using kitsch aesthetics. Hillen’s œuvre interrogates the power of visual images in our society of the spectacle, to use Guy Debord’s expression.7

Concluding this section, Wesley Hutchinson’s ‘“A Remnant in the Land”: The Ulster Scot, Writing and Resistance’ shows how, since the ‘revival’ of the 1990s, Ulster-Scots culture has been the butt of concerted, often virulent criticism from a variety of quarters, especially from within the broad nationalist community, but also from within unionism. However, hostility to the Ulster-Scots community due to suspicion of the political and cultural motives of its members is by no means a recent phenomenon. Hutchinson looks at evidence within the tradition indicating the ways the Scots in Ulster have not only responded to outside pressures but have also challenged rigidities within their own ranks. With examples of writing from the seventeenth century up to the present day, this paper sheds light on the Ulster Scot vision of the Ulster Scots themselves, offering an image which challenges the stereotypes their detractors – and some of their defenders – have sought to foist upon them. Indeed, what appears today as a predominantly conservative strand of the cultural landscape has historically been closely associated with a radical discourse and with forms of resistance that articulated independent readings of events and challenged dominant norms – including those forged by the community itself.

The next part of the volume looks at how Irish literature has tackled the cultural and political landscape through parody and satire. Sylvie Mikowski ← 5 | 6 → opens this section with a meticulous study of Molly Keane’s trilogy – Good Behaviour (1981), Time after Time (1983), and Loving and Giving (1988) – which was published at a later stage in her career and started under the name of M. J. Farrell. While some situate it in the tradition of the Big House novel, others prefer that of the Anglo-Irish satire or of the comedy of manners. This article ponders whether these novels qualify for one or other of these categorisations. Often defined as ‘black’, Keane’s comedy relentlessly focuses attention on the most gruesome, grotesque, and even repulsive elements of bodily life, to such a point that several critics have based their readings of her works on Kristeva’s definition of the ‘abject’.8 This article shows how Keane can be traced back to a number of Anglo-Irish writers, as well as to the writings of some of her contemporaries, including Samuel Beckett, himself an Anglo-Irish writer and as such heir to the same tradition of scathing satire and black comedy.

In a daring yet highly pertinent parallel, Anne Goarzin bridges the 400-year gap between two Irish authors, Jonathan Swift (in Gulliver’s Travels, A Modest Proposal or in his later verse) and Paul Durcan (particularly in his recent collection, The Days of Surprise), examining how both expose and fight their own hubristic times in which Yahoos seem to have taken over. As ‘King(s) of the mob and monarch(s) of the liberties’, both authors are committed to a nation which has yet to define itself, or which is looking back on itself with bitter irony, most notably as Durcan addresses the 1916 commemorations. Both authors point their finger at the forgotten bodies and voices that are being denied an existence by the political and economic machine crushing them, whether it be the colonial machine for Swift or the violence of the global economy and the ensuing recession for Durcan. Here, rhetoric serves the purpose of an indignation that constantly verges on irreverence.

Vito Carrassi’s essay, ‘Deconstructing and Reconstructing Irish Folklore: The Irreverent Parody of An Béal Bocht’, examines this classic by Flann O’Brien, one of the most irreverent observers of the cultural phenomena of twentieth-century Ireland and chiefly of those concerned with ← 6 | 7 → the rediscovery, enhancement and exploitation of Gaelic literature and folklore. Carrassi shows how Flann O’Brien’s approach to the traditional heritage was ‘performative’, as his works, in particular At Swim-Two-Birds, yield innovative as well as hilarious, mocking, subversive results. In doing so, he reflects the factual nature of folklore as a ceaseless process, recreating a given tradition, but also undermining and deconstructing an idea of Irish folklore claimed by most of his contemporaries who were committed to the (re)construction of a Nation. Through An Béal Bocht, his Gaelic novel, Myles na gCopaleen (alias Flann O’Brien) provides a grotesque, sarcastic, surreal parody of an ‘exotic’, fabricated, neo-colonialist view of Irish folklore.

Francois Sablayrolles concludes this section with an article on Seán Ó Faoláin and de Valera. Arguably one of the most prominent intellectuals of his time, Seán Ó Faoláin was also one of the most irreverent and provocative, who tackled head on the totems of what he called ‘de Valera’s dreary Eden’. In his youth, however, Ó Faoláin had been profoundly affected by the brutality of the British repression of the 1916 Rising and was swept along by the wave of idealism that led him to join the ranks of the anti-treaty armed resistance movement. However, his hopes were dashed by the emergence in the 1920s and 1930s of a morally repressive as well as ideologic-ally and politically conservative Ireland. Ó Faoláin’s decision to return to live in Ireland and to confront the power of the Censorship Board which had already banned his first collection of short stories, Midsummer Night Madness (1932), bears witness to his engagement and to his conception of writing, whether it be fiction, biography, or essay, as an act of resistance. This article examines how, by providing an outlet to bypass the Censor, his biographies of Constance Markievicz, Éamon de Valera, and Daniel O’Connell enabled Ó Faoláin to challenge the dominant nationalist discourse and to promote an alternative reading of modern Ireland’s history and identity. Ó Faoláin’s experiments in biography and fiction gave rise to numerous mutually enriching stylistic exchanges. Indeed, the presence of the grotesque, of irony, and also of caricature, allows for the construction of an irreverent, and at times subversive, discourse designed to push icons ‘off their pedestal’.

The final section of this volume is dedicated to the performance of irreverence on the stage. It starts off with an essay by Eugene McNulty ← 7 | 8 → entitled ‘Once More With Feeling: Restaging History in the Work of Gerald McNamara’ (Gerald MacNamara being the penname of Harry Morrow, one of the most successful writers to emerge from the nationalist cultural revival in early twentieth-century Belfast). McNulty not only shows how he was the most innovative and creatively ambitious playwright to be associated with the Ulster Literary Theatre, but also how his parodic works (such as Suzanne and the Sovereigns [1907], The Mist that does be on the Bog [1909], and Thompson in Tir-na-nOg [1912]) represent some of the most fascinating responses of northern cultural nationalism to the emergence of an increasingly Ulster-centric Unionism in the years before partition. By way of his extraordinary satiric sensibility, MacNamara sought to unpack, and resist, the pretensions and politically repressive mythologies of Ulster politics during one of its formative historical phases. His work for the Ulster Literary Theatre in particular marks one of the high points of Northern Irish parody and carnivalesque oppositional cultural energy. This essay traces these oppositional energies in their various political, social, and cultural contexts, and in so doing reveals MacNamara as a crucial, but often overlooked, progenitor of the modern Northern Irish satirical tradition.

Details

- Pages

- VIII, 266

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787077089

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787077096

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787077102

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781787077072

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11401

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (February)

- Keywords

- Irish Studies Non-violent resistance Irreverence Humour Satire Caricature

- Published

- English: Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2018. VIII, 266 pp., 1 fig. col., 29 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG