Summary

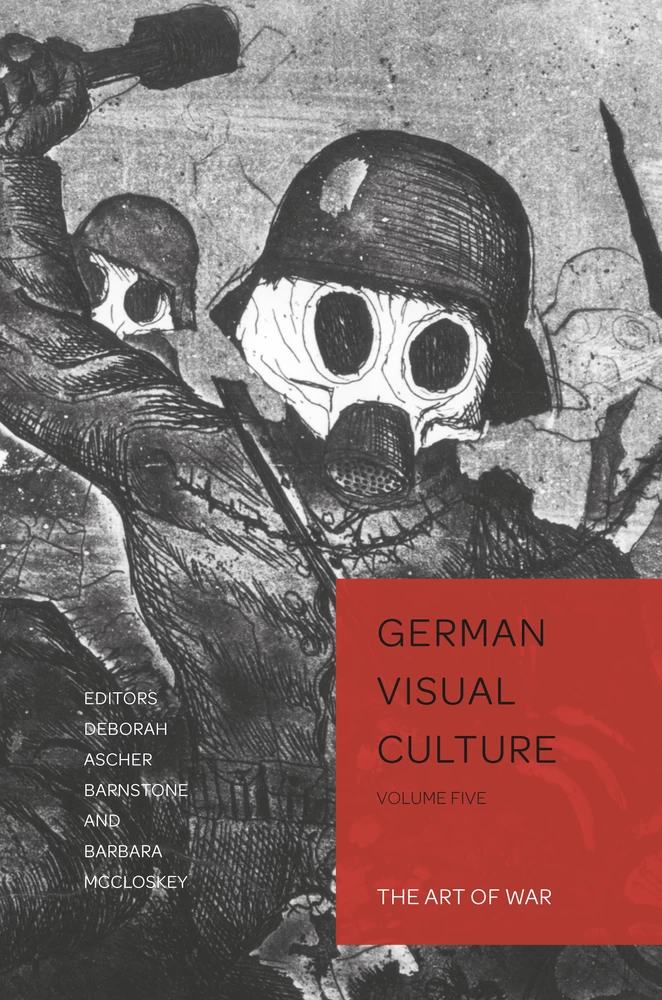

The central concerns of the volume are the multivalent aspects of art that respond to war. It begins by considering art conceived of and executed in response to the First World War on the centennial anniversary of that event. The volume goes on to examine art in the wake of the Holocaust and artistic responses to more recent conflict, such as the Vietnam War. The essays in this volume explore a variety of media – including paintings by Otto Dix and Gerhard Richter, Holocaust photography by Heimrad Bäcker, and sculpture by Emy Roeder, Gela Forster, and Renée Sintenis – to chart the complex relationship between art and war in both its documentary and analytical functions.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Introduction: What Can Art Do? (Barbara McCloskey)

- Part I: Artistic Responses to World War I

- 1 World War I, German Art, and Cultural Trauma: The Birth of the “Degenerate Art” Exhibition from the “Spirit of 1914” (Robert C. Kunath)

- Introduction

- Cultural War and Cultural Trauma

- War and Art

- Conclusion: Toward the “Degenerate Art” Exhibition

- Author’s Acknowledgments

- 2 Max Liebermann’s Kriegszeit Lithographs: Pro-war or Anti-war? (Deborah Ascher Barnstone)

- Kriegszeit and the War

- Lithographs from 1914

- Lithographs from 1915

- Lithographs from 1916

- Conclusion

- 3 Women, War, and Naked Men: German Women Sculptors and the Male Nude, 1915–1925 (Nina Lübbren)

- Introduction

- Emy Roeder’s Torso of a Boy (1915)

- Gela Forster’s Man (1919)

- Renée Sintenis’s The Boxer Erich Brandl (1925)

- Conclusion

- 4 Dix Petrified (James A. van Dyke)

- The Right Panel in Context

- The Good Soldier

- Dix Petrified

- The Politics of Petrification

- Part II: World War II and Holocaust Memory

- 5 “All of a sudden, there was this split”: Heiner Müller’s Poetics of Trauma (Katrin Dettmer)

- War without Battle

- The Scab

- Chicken Face

- 6 Heimrad Bäcker: Photography at the Limits of Understanding the Holocaust and its Violence (Justin Court)

- 7 Aftershocks: (Missing) Holocaust Photographs and Writing the Past in Uwe Johnson’s Jahrestage and W. G. Sebald’s “Max Ferber” (David Kenosian)

- Part III: Reverberations of the Traumatic Past in Recent German Visual Culture

- 8 Horst Faas, Thomas Billhardt, and the Visual Vietnam War in the Two Germanys (Annette Vowinckel)

- The Picture War

- Horst Faas: A West German Photojournalist in Saigon

- Thomas Billhardt: An East German Photojournalist in Hanoi

- A German Approach to the Vietnam War?

- 9 This Sum of Catastrophes: Excavating the History of Joseph Beuys’s 7000 Oaks (Andrea Gyorody)

- The Iconography of 7000 Oaks

- 7000 Oaks at Thirty

- 10 Deferring Perspective in Times of Urgency: Louise Lawler Looks at Gerhard Richter’s Painting of the Air War (Svea Braeunert)

- Gerhard Richter’s Painting of the Air War

- Vertical Sovereignty

- Louise Lawler’s (No) Drone Vision

- Anamorphosis as a Visual Form of Multidirectional Memory

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Series index

Robert C. Kunath – World War I, German Art, and Cultural Trauma: The Birth of the “Degenerate Art” Exhibition from the “Spirit of 1914”

Figure 1.1Punch, August 23, 1914.

Figure 1.2Life, September 26, 1918.

Deborah Ascher Barnstone – Max Liebermann’s Kriegszeit Lithographs: Pro-war or Anti-war?

Figure 2.1“Ich kenne kein parteien mehr,” the Kaiser’s famous Balcony Speech on August 1, 1914 at the beginning of World War I, Max Liebermann, Kriegszeit.

Figure 2.2A more typical rendition of the Kaiser’s famous proclamation with the words “The German People” at the bottom.

Figure 2.3“Jetzt wollen wir sie dreschen!,” Max Liebermann, Kriegszeit.

Figure 2.4The cover of the Drescher Lied songbook.

Figure 2.5“Wohlauf Kameraden, aufs Pferd, aufs Pferd,” Max Liebermann, Kriegszeit.

Figure 2.6“Samaritans,” Max Liebermann, Kriegszeit.

Nina Lübbren – Women, War, and Naked Men: German Women Sculptors and the Male Nude, 1915–1925

Figure 3.1Emy Roeder, Knabentorso [Torso of a Boy], 1915 (artificial stone, dimensions unknown, lost or destroyed); reproduced in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, vol. 43 (1918–19), p. 16. Photograph courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. ← vii | viii →

Figure 3.2Gela Forster, Der Mann [Man], 1919 (material and dimensions unknown, lost or destroyed); reproduced in Neue Blätter für Kunst und Dichtung (1919), Knaus reprint 1970, vol. 2/3, pp. 50–1. Photograph courtesy of University Library Cambridge.

Figure 3.3Renée Sintenis, Der Boxer Erich Brandl [The Boxer Erich Brandl], 1925 (bronze, 40.5 cm, Museum Ludwig, Cologne). Photograph © Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne, inv.nr.rba_c011233.

Figure 3.4Frieda Riess, Der Boxer Erich Brandl [The Boxer Erich Brandl], 1925; reproduced in Der Querschnitt 5/9 (1925). Photograph courtesy of Ullstein Bild.

Figure 3.5Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Der Gestürzte [Fallen Man], 1915/16 (bronze, 65 × 236 × 66.5 cm, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich – Pinakothek der Moderne). Photograph © Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne, inv.nr. rba_1943.

James A. Van Dyke – Dix Petrified

Figure 4.1Otto Dix, Self-Portrait as Mars, 1915 (oil on canvas, 81 × 66 cm). Städtische Sammlungen Freital © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Figure 4.2Otto Dix, That’s How I Looked as a Soldier, 1924 (ink on paper, 43 × 34.3 cm). Here as reproduced in the brochure of the Otto Dix mid-career retrospective at the Galerie Nierendorf in Berlin in 1926. Photograph courtesy of the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Munich © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. ← viii | ix →

Figure 4.3Otto Dix, The War (Triptych), 1929/32 (mixed media on wood, middle panel 204 × 204 cm, left and right panels each 204 × 102 cm, predella 60 × 204 cm). Albertinum/Galerie Neue Meister, Gal.-Nr. 3754. Photograph courtesy of Albertinum/Galerie Neue Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Elke Estel/Hans-Peter Klut © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Figure 4.4Pasquino Group (marble, Roman copy after a Hellenistic original of the third century BC, with modern restorations). Found in Rome, in the Medici collections in Florence, 1570; installed in the Loggia dei Lanzia since 1741. Photograph © Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 4.5Model for a war memorial by Paul Merling, circa 1932. Published in Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung 41/43 (October 30, 1932): 1412. Photograph courtesy of the author.

Katrin Dettmer – “All of a sudden, there was this split”: Heiner Müller’s Poetics of Trauma

Figure 5.1Der Lohndrücker [The Scab], directed by Heiner Müller, Deutsches Theater Berlin 1987/88 © Sibylle Bergemann/Nachlass Sibylle Bergemann/courtesy Loock/OSTKREUZ.

Figure 5.2Der Lohndrücker, directed by Heiner Müller, Deutsches Theater Berlin 1987/88 © Sibylle Bergemann/Nachlass Sibylle Bergemann/courtesy Loock/OSTKREUZ.

Figure 5.3Der Lohndrücker, directed by Heiner Müller, Deutsches Theater Berlin 1987/88 © Sibylle Bergemann/Nachlass Sibylle Bergemann/courtesy Loock/OSTKREUZ. ← ix | x →

Justin Court – Heimrad Bäcker: Photography at the Limits of Understanding the Holocaust and its Violence

Figure 6.1Heimrad Bäcker, Iron Remnants in Foundations in the Great Hall of the Mauthausen Concentration Camp, n.d. (photograph, 15 7/8 × 12 in). Courtesy of Michael Merighi.

Figure 6.2Rail entrance to Auschwitz after liberation, Poland 1945. Bundesarchiv, B 285 Bild-04413/Stanislaw Mucha.

Figure 6.3Heimrad Bäcker, Traces of Labor in the Wiener Graben Quarry in the Mauthausen Concentration Camp, n.d. (photograph, 15 7/8 × 12 in). Courtesy of Michael Merighi.

Figure 6.4The fourth “Sonderkommando” photograph. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 6.5Heimrad Bäcker, Crematorium and Cooling Plant in Mauthausen, n.d. (photograph with paper backing, 8 1/4 × 11 5/8 in). Courtesy of Michael Merighi.

David Kenosian – Aftershocks: (Missing) Holocaust Photographs and Writing the Past in Uwe Johnson’s Jahrestage and W. G. Sebald’s “Max Ferber”

Figure 7.1An unnamed city at night that Sebald includes in his narration of Manchester. The absence of people here and similar images of the city streets reinforce the theme of death in the story. Published in Sebald’s “Max Aurach,” Die Ausgewanderten (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1994). Reproduced with the permission of Wylie Agency UK.

Figure 7.2Tombstone of German-Jewish writer included in the reconstruction of Ferber’s family chronicle. ← x | xi → The feather stands out more prominently than the inscription so as to underscore the identity of the deceased as writer. Published in Sebald’s “Max Aurach,” Die Ausgewanderten (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1994). Reproduced with the permission of Wylie Agency UK.

Figure 7.3Weavers in the ghetto at Lodz taken by Walter Genewein. Photograph A-311 from the collection of the Jüdisches Museum in Frankfurt. Reproduced with the permission of the Jüdisches Museum.

Figure 7.4Book burning in Würzburg. The photograph was a montage used in Nazi propaganda, as Ferber notes. Published in Sebald’s “Max Aurach,” Die Ausgewanderten (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1994). Reproduced with the permission of Wylie Agency UK.

Annette Vowinckel – Horst Faas, Thomas Billhardt, and the Visual Vietnam War in the Two Germanys

Figure 8.1Horst Faas, “A father holds the body of his child,” March 19, 1972. AP photograph.

Figure 8.2Horst Faas, “Hovering US Army helicopters pour machine gun fire into the tree line,” March 1965. AP photograph.

Figure 8.3Thomas Billhardt, Fotografie (Berlin: Braus, 2013), Cover.

Figure 8.4K. J. Wendlandt, “Ein Junger Sproß der Plakatkunst,” Neues Deutschland, August 31, 1983, p. 4. Illustration: Vietnam poster with photo by Thomas Billhardt.

Figure 8.5Thomas Billhardt, A female Viet Cong capturing an American pilot, ca. 1967/8 © Thomas Billhardt/Camera Work. ← xi | xii →

Andrea Gyorody – This Sum of Catastrophes: Excavating the History of Joseph Beuys’s 7000 Oaks

Figure 9.1Beuys and colleagues plant the first oak on Friedrichsplatz, March 16, 1982. Photograph: Dieter Schwerdtle, courtesy of documenta Archiv © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Figure 9.2Basalt stele piled on Friedrichsplatz, 1982. Photograph: Dieter Schwerdtle, courtesy of documenta Archiv © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Figure 9.3Joseph Beuys, The End of the Twentieth Century, 1983–5, basalt, clay, and felt © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photograph © Tate, London 2015.

Svea Braeunert – Deferring Perspective in Times of Urgency: Louise Lawler Looks at Gerhard Richter’s Painting of the Air War

Figure 10.1Installation view, Louise Lawler, “No Drones,” Sprüth Magers, London, November 23–December 23, 2011 © Louise Lawler. Courtesy Sprüth Magers.

Introduction: What Can Art Do?

Our culture demands a lot from art. We expect art to please, uplift, inspire or help change us in some way, if only for a moment. And this expectation persists even as our belief in the capacity of art to do much of anything has waned. This mix of hope and cynicism concerning the power and purpose of art holds especially true for works that treat violent, painful events. Long traditions of documentary reportage operate on the assumption that the encounter with images of atrocity and injustice can move us to act for the purpose of preventing and ending recurrences of violence and pain. Etched in our visual memories are photographs of the Spanish Civil War, the Holocaust, the war in Vietnam, and the current slaughter and refugee crises spawned by conflict in the Middle East. At different times and in various places these photographs reverberate in public opinion by helping to raise awareness and shift consciousness, sometimes in the direction of peace and justice, sometimes not. In any event, violence, atrocities, and the infliction of pain persist regardless of how many heart-rending images call us to account for the rapaciousness we continue to inflict on one another and the world we inhabit. This is our contemporary condition, one awash in images and technologies of communication and destruction that confront us over and over again with our capacity for inhumanity and seeming incapacity to do much about it. What can art do in these circumstances?

Details

- Pages

- XII, 306

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787073845

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787073852

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787073869

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781787073838

- DOI

- 10.3726/b10884

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (December)

- Keywords

- German art history German cultural history German cultural studies trauma studies

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2017. XII, 306 pp., 4 coloured ill., 35 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG