Listening to the French New Wave

The Film Music and Composers of Postwar French Art Cinema

Summary

Listening to the French New Wave offers the first detailed study of the music and composers of French New Wave cinema, arguing for the need to re-hear and thus reassess this important period in film history. Combining an ethnographic approach with textual and score-based analysis, the author challenges the idea of the New Wave as revolutionary in all its facets by revealing traditional approaches to music in many canonical New Wave films. However, musical innovation does have its place in the New Wave, particularly in the films of the marginalised Left Bank group. The author ultimately brings to light those few collaborations that engaged with the ideology of adopting contemporary music practices for a contemporary medium.

Drawing on archival material and interviews with New Wave composers, this book re-tells the story of the French New Wave from the perspective of its music.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Translations

- Prologue

- Part I: The Cahiers Directors

- Chapter 1: Music and Cinema in Postwar Paris: A Cultural History

- Chapter 2: New Wave, New Music? Film Music Collaborations on the Right Bank

- Chapter 3: The French New Wave: A Musical Revolution?

- Part II: The Left Bank Group

- Chapter 4: Musicalising Moving Photographs: The Early Film Music of Agnès Varda

- Chapter 5: Musical ‘Madeleines’ in the Early Cinematic Essays of Chris Marker

- Chapter 6: Alain Resnais: ‘Auteur Mélomane’

- Epilogue

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series Index

| ix →

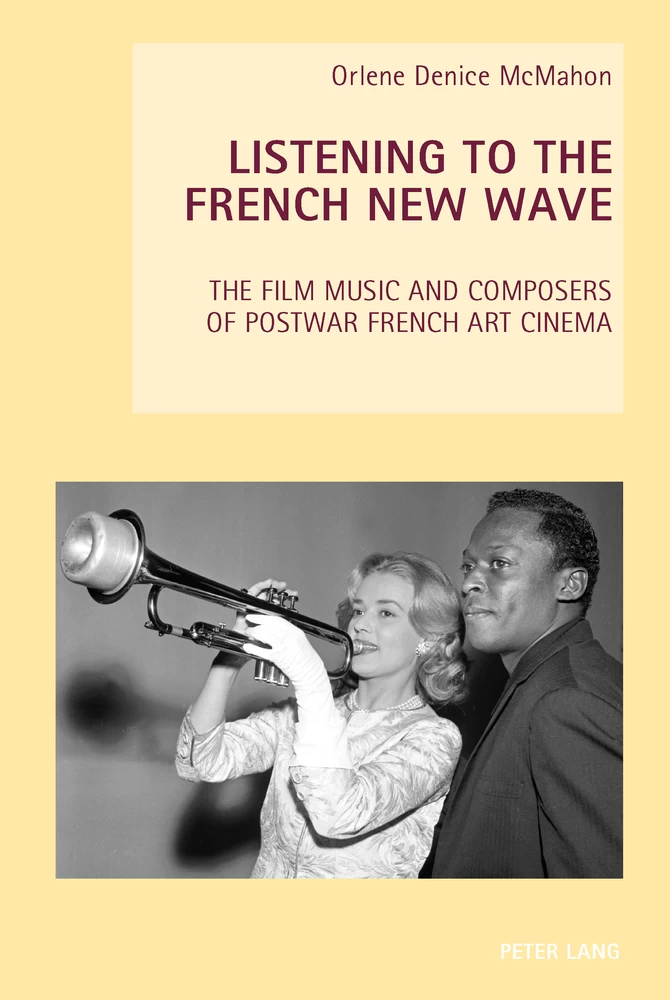

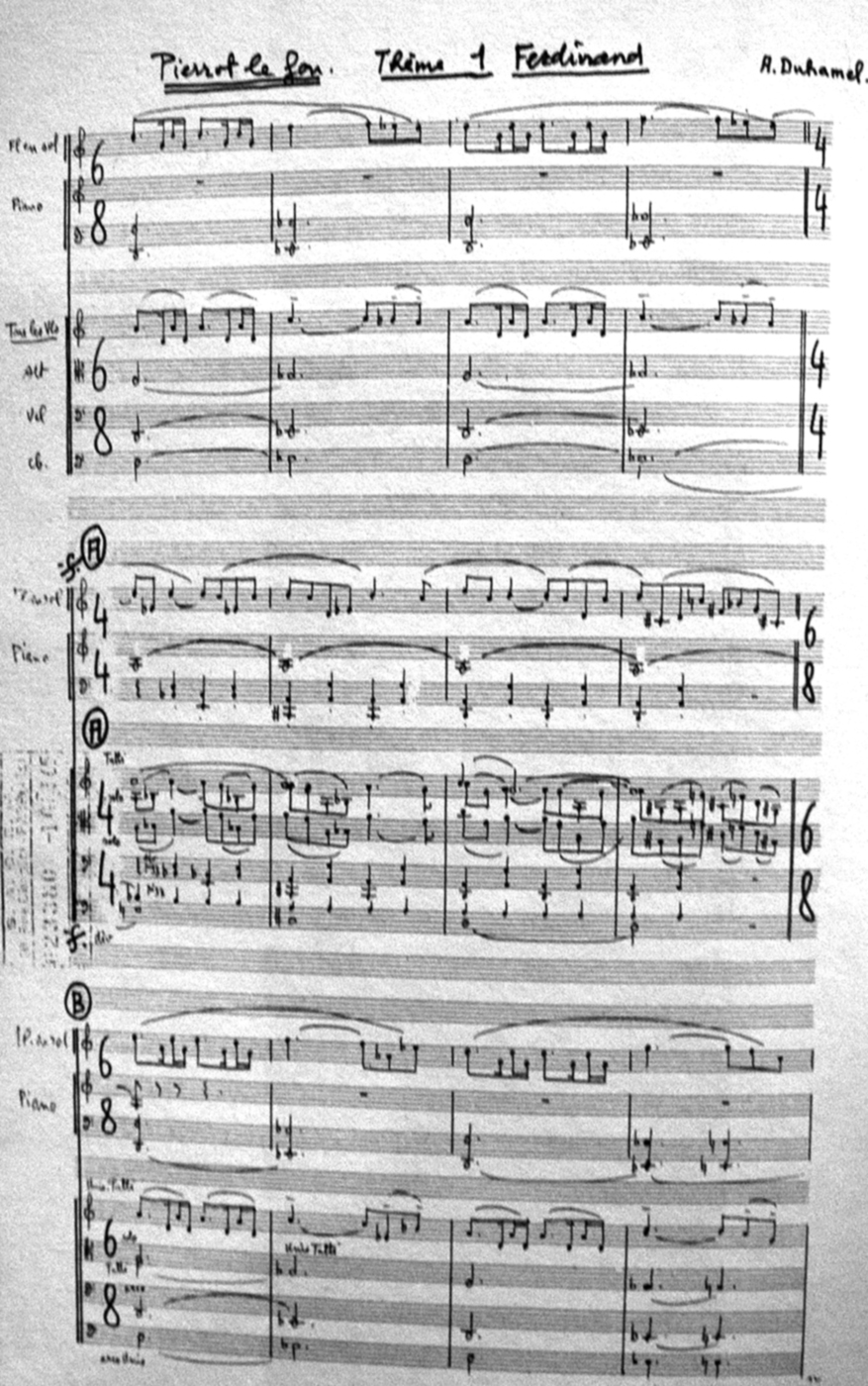

1 Top: Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina in Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le fou (1965) © Studiocanal Image.

Bottom: Composer Antoine Duhamel (1925–) © Jerôme Witz.

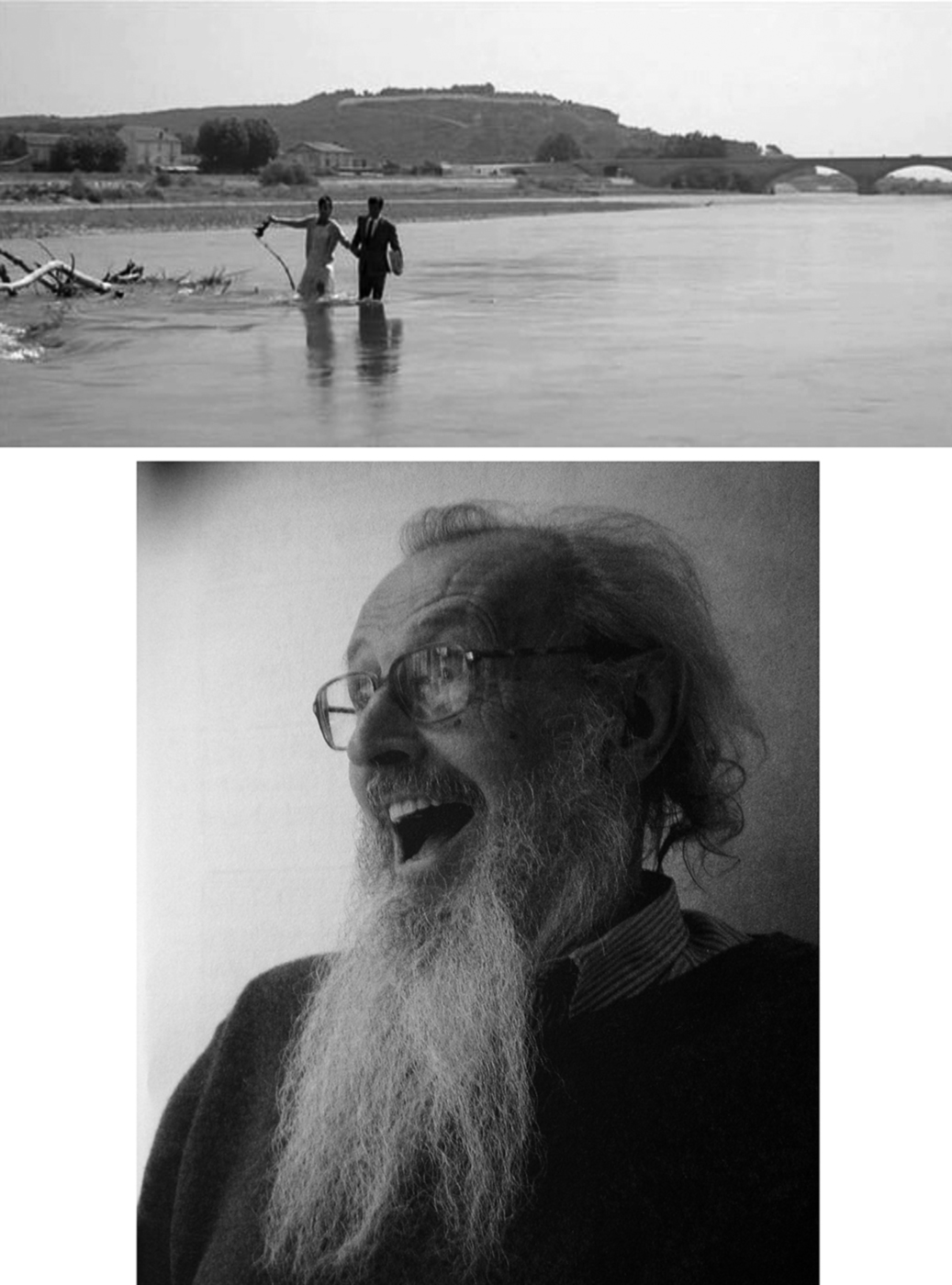

2 Musical Theme ‘Ferdinand’ from Duhamel’s score for Godard’s Pierrot le fou. Reproduced with the kind permission of Duhamel © 1965 Sido Music.

3 Top: Photo of Georges Delerue with François Truffaut on the set of Le dernier métro (1968) © Photo courtesy of Colette Delerue.

Middle: Photo of Pierre Jansen, 2007 © Marion Kalter.

Bottom: Photo of Michel Legrand, 1962 © La Cinémathèque française.

4–7 Excerpts and Compositional Sketches from Jean-Claude Eloy’s score for Jacques Rivette’s La religieuse. Reproduced with the kind

permission of Eloy.

8–9 Excerpts from Eloy’s score for Jacques Rivette’s L’amour fou.

10–12 Three piano pieces by Pierre Barbaud dedicated to the three Left Bank Filmmakers: Agnès Varda, Chris Marker, and Alain Resnais © L’Association

Pierre Barbaud.

13 The ‘Tcherepnin Scale’.

14–16 Excerpts from Pierre Barbaud’s score for Agnès Varda’s La pointe courte. Reproduced with the kind permission of Nicolas Viel © L’Association Pierre Barbaud.

17 An example of Agnès Varda’s beautifully composed photographic camerawork (La pointe courte).

18–19 Excerpts from Pierre Barbaud’s score for Agnès Varda’s La pointe courte. Reproduced with the kind permission of Nicolas Viel © L’Association Pierre Barbaud.

← ix | x →

20 Excerpt from Barbaud’s score for Agnès Varda’s Les créatures.

21 Excerpts from Barbaud’s score for Chris Marker’s Dimanche à Pékin.

22–24 Excerpts from Barbaud’s score for Chris Marker’s Lettre de Sibérie.

25 Still image of the jetty at

Orly airport (Chris Marker’s La jetée).

26 Reaction to the violent scene on the jetty (Chris Marker’s La jetée).

27 Still images of the ‘camp police’ and their ‘mad’ prisoners (Chris Marker’s La jetée).

28 Experimentations carried out on the film’s protagonist (Chris Marker’s La jetée).

29 Recollection-images from the man’s memory (Chris Marker’s La jetée).

30 Marker’s clin d’oeil to Hitchcock’s Vertigo (Chris Marker’s La jetée).

31 Marker’s clin d’oeil to the theme of spirals in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (Chris Marker’s La jetée).

32 La jetée’s denouement revealed in the film’s final scenes.

33 Transcription of Pyotr Goncharov’s chant ‘We bow down before thy cross’ (‘Krestu Tvoyemu’) (Chris Marker’s La jetée).

34 Excerpt from Barbaud’s score for Alain Resnais’ Le chant du styrène.

35 Top: Georges Delerue’s Waltz for Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour.

Bottom: Theme of Forgetting © Henri Colpi.

36–38 Excerpts from Giovanni Fusco’s score for Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour ©

Henri Colpi.

39 Images accompanying the Ruins Themes (Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour).

40 Illustrated extract from River Theme (Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour).

← x | xi →

41 Recollection Scene (Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour).

42 Illustrated Extract from Nevers Theme (Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour).

43 Images from the riverside café showing the woman transfixed in memory (Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour).

| xiii →

For making the past few years spent between Cambridge and Paris the most culturally and academically rewarding of my life, I have many people to thank.

For supporting my research since its embryonic stages, I am indebted to the National University of Ireland, the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the Robert Gardiner Memorial Trust, the Cambridge European Trust, the Faculty of Music at Cambridge, and Gonville & Caius College.

Other debts are harder to quantify: I would like to thank Emma Wilson, Isabelle McNeill, Jeremy Thurlow, Jenny Chamarette, Holly Rogers, Nicholas Cook, and Annette Davison, all of whom provided thought-provoking discussion and vital feedback on my work at important stages during my research. In Paris, Stéphane Lerouge, Antoine de Baecque, Michel Chion, Frédéric Gimello-Mesplomb, and Samuel Petit (BiFi) were invaluable fountains of knowledge on the French New Wave. Indeed, without Stéphane Lerouge, I may never have met the composers who are so integral to this study. For their enthusiasm and willingness to share their stories, I am forever indebted to Antoine Duhamel, Pierre Jansen, Jean-Claude Eloy, and Michel Legrand. Likewise, my thanks go to Colette Delerue and Nicolas Viel (Pierre Barbaud Association) for allowing me to access their private archives.

For revising and refining my translations, I am forever indebted to Sara Kendall Greenberg’s ‘oeil de lynx’. Especially tender thanks go to Jamie O’Connell for being a constant source of friendship and encouragement throughout.

For his unrelenting patience, support, and guidance during my time at Cambridge, I am forever grateful to Ben Walton. His foresight, wisdom, and skilful rhetoric have always pointed me in productive directions. Finally, Guillaume Fournié has made me laugh every day since the ← xiii | xiv → moment we met. Without his love, support, and positivity, this work would not have come to fruition. To him I dedicate this book with love and gratitude.

Paris, October 2013

| xv →

All translations are mine unless otherwise stated. I have included the original French of unpublished interviews in footnotes, where appropriate.

← xv | xvi →

Figure 1: Top: Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina in Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le fou (1965) © Studiocanal Image.

Bottom: Composer Antoine Duhamel (1925–) © Jerôme Witz.

← xvi | xvii →

Figure 2: Musical Theme ‘Ferdinand’ from Duhamel’s score for Godard’s Pierrot le fou. Reproduced with the kind permission of Duhamel © 1965 Sido Music.

| 1 →

La Cinémathèque française, Paris, February 24, 2007. The lights go down in the Henri Langlois theatre and the cinema screen comes to life with a panoramic shot of Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina, hand in hand, traversing the Durance River (see Figure 1). For cinéphiles, it is an iconic scene. Yet, on this wintry afternoon, the Cinémathèque are paying homage neither to the film from which it is taken (the 1965 Pierrot le fou), nor to the film’s director, Jean-Luc Godard, but rather to a tall, distinguished-looking gentleman, with a long grey beard, giddy eyes, and a mischievous grin. This is Antoine Duhamel, the octogenarian French composer, former student of Olivier Messiaen, and composer of the film’s score (see Figure 2). Although I am an aficionado of both music and cinema, this was my first encounter with Duhamel’s name and the first time I had consciously listened to the music in one of my favourite French films.

This experience can serve as a reminder of the attention, or lack of it, that both film music and its creators receive. In order to address this phenomenon in relation to a single national cinematic tradition, this study focuses on the music and composers (Duhamel included) of the French New Wave. Still, as perhaps the most studied film movement in cinema history, the sheer extent of scholarship on the New Wave raises the question of whether it is possible to write anything new about this period.1 For over five decades, the New Wave has been analysed and criticised, romanticised and mythologised. Volumes abound on its birth, death, and legacy, whilst scholars and critics have approached the movement from almost every possible analytical angle: historical, ← 1 | 2 → generational, theoretical, socio-cultural, and, more recently, in relation to issues of gender.2 Indeed, as 2009 marked the fiftieth year since the ‘official birth’ of the French New Wave, reconsiderations of its influence formed the focus of many international retrospectives, conferences, and festivals.3 Its revolutionary credentials and its canonical boundaries were questioned and tested in order to allow for expanded understandings of the movement in light of new historical and cultural contexts.

Yet there are still some gaps, and the study of music in New Wave films is one of the most striking. To my knowledge, there has been no other book-length study carried out on New Wave film music; rather, there have been chapter articles, sections of books, and papers written on music in individual New Wave films or on the music of specific New Wave directors.4 Particularly important among these writings are the works of French film and film music scholars, both recent and contemporary to the French New Wave. As perhaps the leading French voice on film sound and music, Michel Chion’s impressive body of work on this area has provided an invaluable contribution to the field.5 His 1995 volume La musique au cinéma is particularly significant here, offering a detailed overview of film music history, from its beginnings in 1895 to the modern day. In terms of the French New Wave, the chapter entitled ‘Des classicismes au modernisme (1935–1975)’ has an especially relevant section under the subtitle ‘Nouvelle Vague française, nouvelle musique?’ – a question that, as detailed below, forms the dialectic of the second chapter of this book.6

← 2 | 3 →

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 300

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035305883

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035398564

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035398571

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034317504

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0353-0588-3

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (March)

- Keywords

- history ethnographic approach ideology

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2014. XVIII, 300 pp., 43 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG