Drones

Media Discourse and the Public Imagination

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

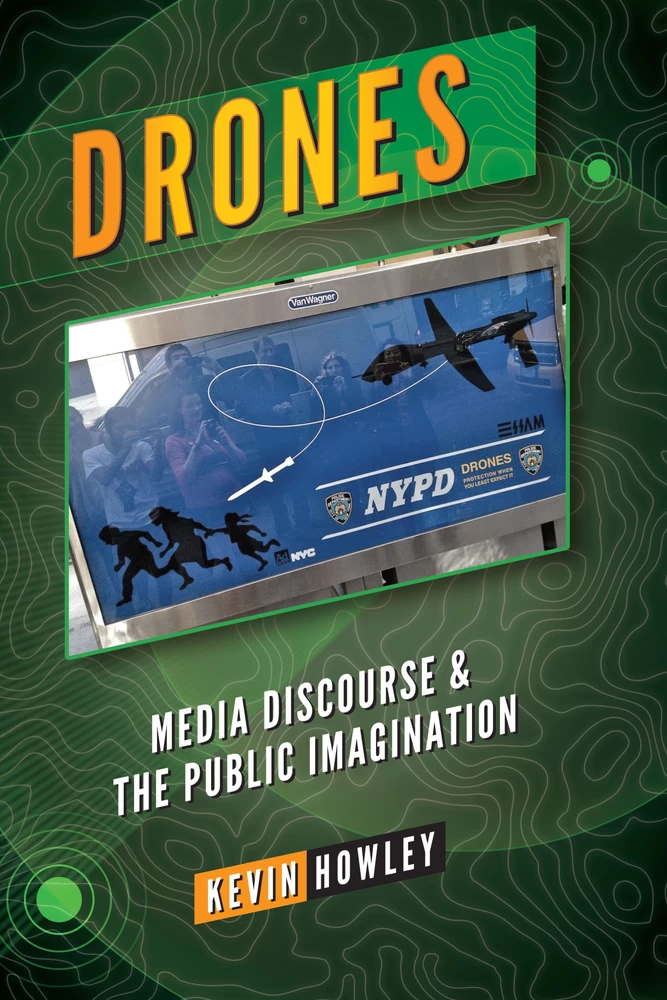

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- Introduction: Don’t Call Them Drones

- Drone Discourse: Power, Hegemony and Resistance

- Discourse Theory: Making Meaning, Constructing Knowledge

- Critical Discourse Analysis: Dominance and Change

- Chapter Outline

- Notes

- References

- Part I: Perpetual War

- 1. Technological Dreams and Killing Machines, or Drones and the Sublime

- The Sublime

- Cultural Antecedents: The Power of Anticipatory Discourse

- Notes

- References

- 2. A New Kind of War

- A Period of Consequences

- Is it Bin Laden?

- The Dawn of Robotic War

- Notes

- References

- 3. Murder Incorporated

- A Major Blow

- Open Secrets and Elastic Definitions

- #StandWithRand

- Notes

- References

- Part II: Domesticating Drones

- 4. Unmanned: Drones for Fun and Profit

- Airborne Enterprise

- Trigger Warnings

- Days of Future Past

- Notes

- References

- 5. Eye in the Sky: New Surveillance Regimes

- Border Security and Domestic Law Enforcement

- Drone Journalism

- Drones for Good

- Notes

- References

- 6. Reporting the Drone Wars

- Language and Power in Reporting the Drone Wars

- Officials Say …

- Personality Strikes and the Anonymous Dead

- Notes

- References

- Part III: Witnessing

- 7. Survivors Speak

- Not a Militant, But My Mother

- Other Voices, Other Drones

- Firsthand Accounts

- Notes

- References

- 8. Mr. Al-muslimi goes to Washington

- A War of Mistakes

- Can I Get a Witness?

- C-SPAN

- Corporate Media

- Public Media

- Notes

- References

- 9. Distributed Intimacies: Robotic Warfare and Drone Whistleblowers

- Distributed Intimacies

- From Digital Witness to Drone Whistleblower

- The Rise and Fall of Remote-Control Warriors

- Notes

- References

- Part IV: Resistance

- 10. Direct Action and Media Activism

- Ground the Drones

- Activist Media Practice

- Creative Resistance

- Notes

- References

- 11. “I have a Drone”: Internet Memes and Digital Dissent

- Internet Memes and Cultural Politics

- Media Narratives and Collective Memory

- Living the Dream

- A Dream Deferred?

- The Dream @ 50

- Drone Memetics

- Split Screens and Moral Failings

- Days of Future Past

- Terror Drones

- References

- 12. Think Locally, Bomb Globally: Satirizing Drones

- Obusha

- From the Sublime to the Ridiculous

- Two Birds with One Drone

- The World’s Policeman

- Well, I’m Not on the List

- Notes

- References

- Conclusion: Twenty-First Century Empire and Communication

- It’s About the Data Link, Stupid

- Drones and the Problems of Time and Space

- Innis and the Discursive Turn

- Drones: The New American Sublime

- Notes

- References

- Index

Figure 1.1: President John F. Kennedy’s goal of putting a man on the moon is emblematic of anticipatory discourse. Photo credit: NASA. Source: Flickr.

Figure 4.1: The DJI Phantom takes flight at the 2015 Consumer Electronics Show. Photo credit: Maurizio Pesce. Source: Creative Commons.

Figure 5.1: Pedestrians photograph Essam Attia’s satirical NYPD drone advertisement. Photo credit: Jason Eppink. Source: Flickr.

Figure 7.1: Nabila Rehman looks on as her brother, Zubair, testifies before a Congressional committee on civilian casualties of the US drone campaign. Photo credit: Jason Reed. Source: Reuters.

Figure 8.1: Farea Al-Muslimi addresses the first-ever US Senate hearing on the targeted killing program. Source: C-SPAN.

Figure 10.1: Peace activists stage a mock drone assault on a funeral procession outside Creech Air Force Base in Nevada. Photo credit: Mauro Oliveira. Source: Code Pink. ← ix | x →

Figure 11.1: Instance of the “I Have a Drone” meme depicting a meeting between Martin Luther King, Jr. and Barack Obama. Source: quickmeme.com/meme/3snodk.

Figure 11.2: “I Have a Drone” creative derivative featuring Vietnam era drone strike with smiling Obama. Credit: William Banzai. Source: WilliamBanzai7.

Figure 12.1: Editorial cartoon critiquing the expansion of George W. Bush’s drone program under Nobel laureate Barack Obama. Credit: Nate Beeler. Source: Cagle Cartoons.

Figure 12.2: Single-panel cartoon draws unflattering comparison between Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama. Credit: Monte Wolverton. Source: Cagle Cartoons.

Books about drones are nearly as commonplace—if not quite so infamous—as these flying machines themselves. In recent years, well-known authors and critics have produced timely analyses of the drone wars from activist, historical, and international relations perspectives. For instance, Medea Benjamin, co-founder of the progressive grassroots organization, Code Pink, published Drone Warfare: Killing By Remote Control. Political reporters Nick Turse and Tom Engelhardt co-authored Terminator Planet: The First History of Drone Warfare 2001–2050. Lloyd C. Gardner’s Killing Machine: The American Presidency in the Age of Drone Warfare examines the implications of weaponized drones for presidential power in the twenty-first century. And America’s most distinguished public intellectual, Noam Chomsky, is co-author, with Andre Vltchek, of On Western Terrorism: From Hiroshima to Drone War. Other titles deal with the legal, strategic, and policy implications of drone warfare. Three notable examples: Brian Glyn Williams’s Predators: The CIA’s Drone War on al Qaeda; Akbar Ahmed’s The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam; and Marjorie Cohn’s Drones and Targeted Killing: Legal, Moral & Geopolitical Issues.

At the same time, researchers from a variety of disciplines—engineering, computer science, international relations, cultural studies, and political ← xi | xii → science—have published scholarly analyses of drones in peer-reviewed journals. Conversely, drones, robotics, and automated killing machines feature prominently in recent popular fiction, from Mike Maden’s Drone (A Troy Pearce Novel) to former counterterrorism czar Richard Clarke’s political thriller Sting of the Drone. Then there’s Don Nardo’s Drones (Military Experience: In the Air), which offers a historical account of weaponized drones for young readers. Drones have even made an appearance in the self-help genre; see, for example, J. J. Best’s UAV Pilot: How to Be Ready for the Coming Drone Pilot Job Boom. And just in time for the gift-giving season, Craig S. Issod authored Getting Started with Hobby Quadcopters and Drones.

Despite growing academic and popular interest, there are no book-length treatments of drones from media and cultural studies perspectives. Nevertheless, as I hope to demonstrate, operating from such a perspective reveals a great deal about the relationship between technology and culture. Specifically, my aim is to offer a comprehensive understanding of the role news stories, advertising, activist media, and popular culture play in constructing public knowledge of this emerging technology. In doing so, this book highlights how media discourse—talk and text, sound and image—shapes and is shaped by technological innovation and artifacts, like drones.

Research support, in the form of a sabbatical leave from DePauw University during the 2014–2015 academic year, was instrumental in getting this project off the ground. Funding through DePauw’s interdisciplinary Conflict Studies program and a subsequent Faculty Fellowship award provided additional time and resources to bring the book to completion. Thanks to my friends and colleagues at DePauw, most notably, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jeff Kenney, Tiffany Hebb, Jin Kim, Geoff Klinger, and especially, Jeff McCall, for their assistance and support as this project moved forward. Further afield, my gratitude goes out to Arthur Holland Michel and the faculty and students at the Center for the Study for the Drone at Bard College for their help during the early stages of my research. Likewise, I’m grateful to Øyvind Vågnes, at the University of Bergen, for his feedback and encouragement during my travels to the 2015 meeting of the American Studies Association of Norway. Thanks also to Mitch Reyes at Lewis & Clark College for organizing two highly productive writing retreats that proved instrumental in bringing this project to completion. Finally, I’d like to thank Kathryn Harrison, Michael Doub and their colleagues at Peter Lang for their professionalism and expertise.

Ultimately, the meaning of a tool is inseparable from the stories that surround it.

—David Nye, Technology Matters: Questions to Live With

A story in Popular Mechanics headlined “Drone Is Not a Four-Letter Word” describes a brief encounter between technology reporter, Joe Pappalardo, and a New York City police officer. Fresh from an appearance on the Fox Business Channel, where he discussed civilian and commercial uses of these suddenly ubiquitous flying machines, Pappalardo attempted to reassure the cop, a veteran of the Afghan War, that he has nothing to fear from unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones. Unconvinced, the officer expressed his discomfort: “If I saw one of these while I was out on my boat, I’d just, you know, shoot it down” (Pappalardo, 2013). The policeman’s unease, Pappalardo observes, is not unique. Sampling social media responses to Amazon’s highly publicized plans for delivering packages by quadcopter, Pappalardo describes public skepticism toward the online retailer’s lofty scheme, and more broadly, the source of profound cultural anxieties articulated by the rise of the drone. The journalist offers several reasons for this skeptical, frequently ← xiii | xiv → apprehensive, popular reaction to drones—concern over public safety and fear of automation, among others—before settling on a somewhat unexpected explanation: language. “I think there’s a linguistic problem here, too, stemming from the use of the word ‘drone.’ The law enforcement and military connotations of the word runs deep,” Pappalardo concludes. It is a plausible interpretation. After all, in the age of drone warfare, with its attendant Orwellian language –“imminent threat,” “enemy non-combatant,” “kinetic military action,” “disposition matrix” and the like—words certainly do matter.

But this isn’t the whole story. Evidently, “drone” is a four-letter word for the very same military personnel who routinely use these aircraft for reconnaissance, surveillance, and targeted killing. During a 2012 interview with NPR, outgoing US Air Force General Norton Schwartz dressed down reporter Tom Bowman for uttering the phrase “drone.” “Drones mischaracterize what these things are,” Schwartz declared. “They’re not dumb. Nor are they unmanned, actually. They’re remotely piloted aircraft” (Bowman, 2012). US Army General Martin Dempsey is equally perturbed by what journalist Aram Roston adroitly refers to as “the D word.” Returning to Washington from a 2014 defense meeting at NATO headquarters in Brussels, Dempsey told reporters, “You will never hear me use the word ‘drone,’ and you’ll never hear me use the term ‘unmanned aerial systems,’ because they are not. They are remotely piloted aircraft” (Garamone, 2014). With its emphasis on highly trained pilots in control of sophisticated, precision aircraft, the military’s designation, better known by the acronym RPA, avoids the gendered nomination, unmanned aerial systems (UAS), preferred by entrepreneurs, trade organizations, and industry groups.

For instance, Ray Mann, a Welsh engineer and owner of “the world’s first civilian airport for drones,” was unequivocal when he told the Sunday Times, “Don’t call them drones. I don’t like the word. It makes people fearful. It has a sinister sound to it” (Gillespie, 2013). Likewise, Lucien Miller, CEO of Innov8tive Designs in Vista, California, is keenly aware of the perception problem entrepreneurs face in light of “Predators and their Hellfire missiles bombing daycare centers in Afghanistan” (Larson, 2014). Small wonder, then, that the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), the industry’s leading trade organization, launched a campaign to persuade journalists to stop using the word “drone” when writing stories about their airborne enterprises. To that end, reporters covering the 2013 AUVSI convention in Washington, DC discovered that the Wi-Fi password in the press room was “DONTSAYDRONE.” ← xiv | xv →

Relishing the irony, Brian Fung (2013) responded with a blog post headlined “Why Drone Makers Have Declared War on the Word ‘Drone.’” Some joke. For the hundreds, perhaps thousands of civilian casualties of America’s drone wars,1 these high-tech killing machines may not be four-letter words, but they most certainly are an obscenity. And yet, the stories of victims and survivors of US drone strikes are rarely heard outside of independent media and the alternative press. What’s more, corporate news media routinely ignore the testimony of former drone operators turned whistleblowers, as well as direct action campaigns waged against drone warfare. Nonetheless, these stories are just as relevant as news accounts of drone strikes across the Islamic world, marketing and advertising copy promoting the latest UAS, and press releases issued by business leaders and local governments extolling the economic and security benefits of UAVs. Indeed, the stories of survivors, witnesses, and resisters are essential if we are to fully comprehend the social, political, and cultural implications of drones.

This book examines the relationship between technology and culture. It starts from the premise that technology shapes and is shaped by the stories we tell about it. As communication scholar James Carey observed:

Stories about technology … play a distinctive role in our understanding of ourselves and our common history. Technology, the hardest of material artifacts, is thoroughly cultural from the outset: an expression and creation of the very outlooks and aspirations we pretend it merely demonstrates. (Carey, 1992, p. 9)

Drawing on insights from media, communication, and technology studies, this book explores how news accounts and op-eds, marketing and advertising, as well as all manner of popular culture construct public knowledge of drones. Throughout, I argue that media discourse plays a decisive role in shaping these new technologies, understanding their application in various spheres of human activity, and integrating them into everyday life. Furthermore, I contend “drone discourse” employs a common trope associated with scientific and technical innovation: the technological sublime (Marx, 1964; Nye, 1994). That is to say, media narratives about drones—at once anxious and hopeful, fearful and awe-inspired—are emblematic of the profound cultural ambivalence that frequently accompanies the introduction of new technologies (Marvin, 1988; Rothstein, 2015). Thus, the book highlights the social construction of technology through critical analysis of the relationship between discursive and material practice. ← xv | xvi →

This introduction proceeds with an analytical framework for examining this relationship. It locates this study in terms of the decisive role media discourse plays in the construction of public knowledge and the politics of culture. Following this, I describe the book’s organization into four thematic sections and offer a rationale for the selection of the specific cases, episodes, and texts examined throughout. As we shall see, critical analysis of a variety of cultural forms—from newspaper headlines, nightly newscasts, and documentary films to advertising, entertainment media, and graphic arts—vividly demonstrates the prevalence of drones in global battlefields and domestic airspace, public discourse and the popular imagination.

Drone Discourse: Power, Hegemony and Resistance

From the outset, it is important to acknowledge that there is no single approach to the study of media discourse. As contributors to Bell and Garrett’s (1998) seminal volume demonstrate, scholars employ a range of analytical frameworks to examine, for instance, opinion and ideology in the press (van Dijk), televisual news discourse (Allan), newspaper design and layout (Kress & van Leeuwen), and language in broadcast media (Scannell). Despite the variety of texts scholars examine, and the diverse approaches they employ, analysts share a common interest in exploring the decisive, but often opaque relationship between mediated discourse and social structures, relations, and interaction. “Media discourse is important,” Bell contends, “both for what it reveals about a society and because it also itself contributes to the character of society” (1998, pp. 64–65). As we shall see, drone discourse exposes, and frequently conceals, a great deal about how, why, and to what ends drone technology has developed historically. Doing so, it reveals profound contradictions in US culture and society—especially America’s “imperial ambitions” in the aftermath of the attacks of September 11, 2001 (Chomsky & Barsamian, 2005).

Furthermore, drone discourse draws upon and recirculates a wellspring of cultural attitudes and sensibilities toward technological innovation more generally (Rothstein). In other words, media representations of drones—the words, sounds, and images that we use, and the stories that we tell—reflect as well as refract popular attitudes toward this new technology. This is not to suggest, however, that drone discourse is unique in this regard: a point taken up in greater detail in Chapter 1 with respect to the technological sublime. For present purposes, then, we begin with a concise review of the ← xvi | xvii → philosophical underpinnings of discourse theory. Following this, I describe the analytical approach employed in this study: critical discourse analysis (CDA). Throughout, I make every effort to avoid too much technical jargon in the hope that this book may appeal to non-specialist and lay audiences who might be unfamiliar with the sometimes esoteric language of critical discourse analysis (Billig, 2008).

Discourse Theory: Making Meaning, Constructing Knowledge

Notwithstanding its application across the humanities and social sciences, from literary studies and social linguistics to narrative theory and discursive psychology, discourse analysis is fundamentally concerned with “language in use” (Smith & Bell, 2007, p. 79). How scholars across these disparate fields define “discourse” is another matter altogether. Drawing on Michel Foucault’s influential work, Charlotte Epstein defines discourse as “a cohesive ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categorizations about a specific object that frame that object in a certain way and, therefore, delimit the possibilities for action in relation to it” (2008, p. 2). Adopting a more abstract definition, Eoin Devereux refers to discourse as “a form of knowledge” (2003, p. 158). Striking a balance between these two descriptions, Marianne Jorgensen and Louise Phillips offer a definition that is parsimonious as it is incisive: “a particular way of talking about and understanding the world (or an aspect of the world)” (2002, p. 1). With its emphasis on the sensemaking dimensions of discourse, Jorgensen and Phillips’ definition is well suited to this project. Indeed, discourse analysis is especially useful for examining the “production and circulation of meaning through language”: a principal concern of contemporary media and cultural studies scholarship (Hall, 1997, p. 1).

Discourse theory starts from a basic assumption regarding the relationship between language and reality. Operating under the rubric of social constructionism (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Burr, 2015), discourse theory holds that language in not a reflection of reality; rather, language plays a decisive role in constituting “the real.” This is not to suggest that naturally occurring phenomenon, like thunderstorms and wildlife, are figments; nor that material artifacts, such as cell phones and airplanes, do not exist. They certainly do. However, our perception and understanding of these objects is mediated through language. As Carey puts it, “Reality is not given, not humanly existent, independent of language and toward which language stands as a pale refraction. Rather, reality is brought into existence, is produced, by communication—by, ← xvii | xviii → in short, the construction, apprehension, and utilization of symbolic forms” (1992, p. 25). Our “access to reality” (Jorgensen & Phillips, p. 5) is, therefore, a product of symbolic forms, like language; and discursive strategies, such as categorization, by which we classify and distinguish, for example, the natural world from the realm of material artifacts. The key insight here is that the meaning of, say, a bird or a drone, is not inherent in the objects themselves. Instead, we ascribe meaning to material reality through discourse.

Additionally, discourse theory holds that symbolic forms and representational systems are historically and culturally specific. For example, we can detect the evolution of the word drone from the middle of the twentieth century to the present day. During WWII, the armed forces used target drones to train pilots and anti-aircraft personnel. At the time, the word “drone” connoted an expendable, inexpensive radio-controlled (RC) aircraft; a far cry from the sophisticated, semi-automated killing machines used in US counterterrorism operations today. Over the course of the past half-century, then, what we mean when we use the word “drone” has changed dramatically. Thus, meaning is never completely fixed, but is historically contingent. What’s more, the process by which material artifacts, like drones for instance, come to be known and understood is culturally specific. In the United States, drones are routinely portrayed as an effective means of combatting terrorism in a safe (for the pilots), efficient, and cost effective manner. Consequently, public opinion polls routinely find a majority of Americans support the targeted killing program, even if a terror suspect is a US citizen.2 Across the Islamic world, however, drones are perceived quite differently.

For a Muslim tribesman, this manner of combat not only was dishonorable but also smacked of sacrilege. By appropriating the power of God through the drone, in its capacity to see and not be seen and deliver death without warning, trial, or judgment, Americans were by definition blasphemous. (Ahmed, 2013, p. 2)

What’s more, flying unseen, but not unheard, for hours and days at a time, drones inflict emotional and psychological trauma on civilian populations (Benjamin, 2015). For communities living under drones, these symbols of American technological ingenuity are a source of sheer terror (Cavallaro, Sonnenberg, & Knuckey, 2012).

Discourse theory further conceptualizes knowledge as a product of social practices, such as formal education, everyday conversation, and most important for our purposes, the daily output of the media and cultural industries. As Roger Silverstone observes, media are central to “our capacity or incapacity ← xviii | xix → to make sense of the world in which we live” (1999, p. ix). Accordingly, this book’s analysis of media discourse reflects the centrality of factual as well as fictional media in the construction of public knowledge. Furthermore, as Jorgensen and Phillips note: “Knowledge is created through social interaction in which we construct common truths and compete about what is true and false” (Emphasis added, 2002, p. 5). Put differently, knowledge is produced, circulated—and frequently contested—through social interaction. Nowhere is this more evident than in ongoing debates over the “accuracy” and “precision” of US drone strikes, let alone widely disputed estimates of civilian casualties in America’s drone wars (Shane, 2011). Hence, the concept “discursive struggle” (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985), herein understood as competing ways of talking about or understanding the world, is of paramount importance to discourse analysis. In the pages that follow, we will explore this discursive struggle as it plays out between various players and interests: from military officials and anti-war activists to government regulators and drone entrepreneurs.

Details

- Pages

- XXXII, 284

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433147425

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433147432

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433147449

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433147418

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433126406

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11986

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (January)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XXXII, 284 pp., 10 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG