Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the Book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Introduction: Henry James in Times Past and Present

- A great deal of history

- A little literature

- References:

- I (Henry) Janus

- Conflicting Identities: The Two Faces of Henry James

- A double cultural affiliation

- The “reverse of the picture”

- The return motif and its ambiguities

- The process of interiorization

- Conclusive remarks

- References:

- Non-Fiction

- Fiction

- Other documents (Alphabetical order)

- Henry James’s Struggle with Writing and Friends

- Introduction

- London and liberal agency

- Liberal agency as a narrative strategy

- Conclusion

- References:

- Henry James letter manuscripts:

- II The Civil War

- “An Obscure Hurt”: Henry James’s Civil War and the Literary Uses of the Confederacy

- References:

- James Comes to Terms with the Civil War and the South: A Round of His Visits to the South in 1904–1905

- Introduction: sesquicentennial of the American Civil War

- The James brothers and the “house divided” within the family

- The Unveiling of Saint-Gaudens’ Bronze Memorial of Colonel Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth in 1897

- A round of James’s visits to Southern cities in 1904–1905

- Conclusion: writing a “harmony of illusions”

- References:

- Henry James’s Sense of the American Civil War in The American Scene

- Introduction

- The student of manners: the analyst as protagonist

- A Southern impression

- Particular application

- General application

- Desperate practice: lessons learnt and re-learnt

- Conclusion

- References

- III The First World War

- Within the Rim: Henry James, War and Insularity

- Outbreak

- “The most beautiful English summer”

- Paradoxes of James’s rhetoric

- Postscript

- References:

- Henry James and Soldiers during World War I: Four Letters

- Photos and captions

- References:

- “Our Murdered Civilization”: Echoes of the Great War in Henry James’s Correspondence and T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land

- Introduction

- A wartime state of mind

- All the dead young men

- The mourning that dare not speak its name

- The city of the living dead

- Between disintegration and hope of deliverance

- Conclusion

- References:

- IV Henry James in Conflict

- Henry James and Julian Hawthorne, or, on the Importance of Name

- References:

- Haunted by James: Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty and the Politics of the Secret

- Introduction: a ghost

- Choosing a line

- An aesthete

- A body

- Conclusion: a legacy

- References:

- Colm Tóibín: “Wrestling” with the Master

- Introduction

- Semblance, approximation, affinity

- Conversations with Henry James

- In the arms of the Master

- References:

- Henry James, Transatlantic Jewishness, and Cynthia Ozick’s Foreign Bodies

- Corrections: from international theme to transatlantic Jewishness

- Mimicry: semitic discourse

- Critique: the question of our reading

- References:

- Postcolonising Henry James: Confrontations

- Introduction

- James and postcolonialism: signalling the possibility in “master volumes”

- James and postcolonialism: exploring the juxtapositions

- Conclusion

- References:

- Internet sources:

- Henry James of the Empire

- References

- V Conflict in Henry James

- Acquisitive Perception and Inner Conflict in Henry James’s Fiction

- Introduction

- Misleading perceptions and inner conflict in James’s early fiction

- Torn between self-image and unnamed desires

- A brief glimpse of freedom

- Epistemological ordeal and conflict in The Ambassadors

- From moral judgment to aesthetic appreciation

- Beyond knowledge and representation

- “Lucid and quiet” – freedom, uncertainty and inner conflict

- Conclusion

- References:

- Jamesian Battles between Desire and Moral Integrity – Capital Dilemmas

- Introduction

- Sexual capital

- The dilemma of love

- Conclusion

- References

- The Spoils of Henry James: Between the Public and the Private

- Introduction

- James and “The Birthplace”

- James and Lamb House

- Conclusion

- References:

- Ghostly Confrontations and Inner Conflict: An Autobiographical Reading of “Owen Wingrave”

- References:

- Amoenus versus Horridus. The Turn of the Screw and the (Counter)Pastoral

- Introduction

- The pastoral tradition

- Locus amoenus and locus horridus

- The Turn of the Screw and the (counter)pastoral

- Conclusion

- References:

- Setting the Scene in Selected Tales by Henry James

- Introduction

- Cognitive Stylistics and Cognitive Linguistics: guiding assumptions and fundamental terminological distinctions

- Towards an analysis of eight text samples

- “The Story of the Year”

- “A Bundle of Letters”

- “Pandora”

- “The Pupil”

- “The Middle Years”

- “The Death of the Lion”

- “The Beast in the Jungle”

- “The Jolly Corner”

- Conclusion

- References:

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Index

| 9 →

Introduction: Henry James in Times Past and Present

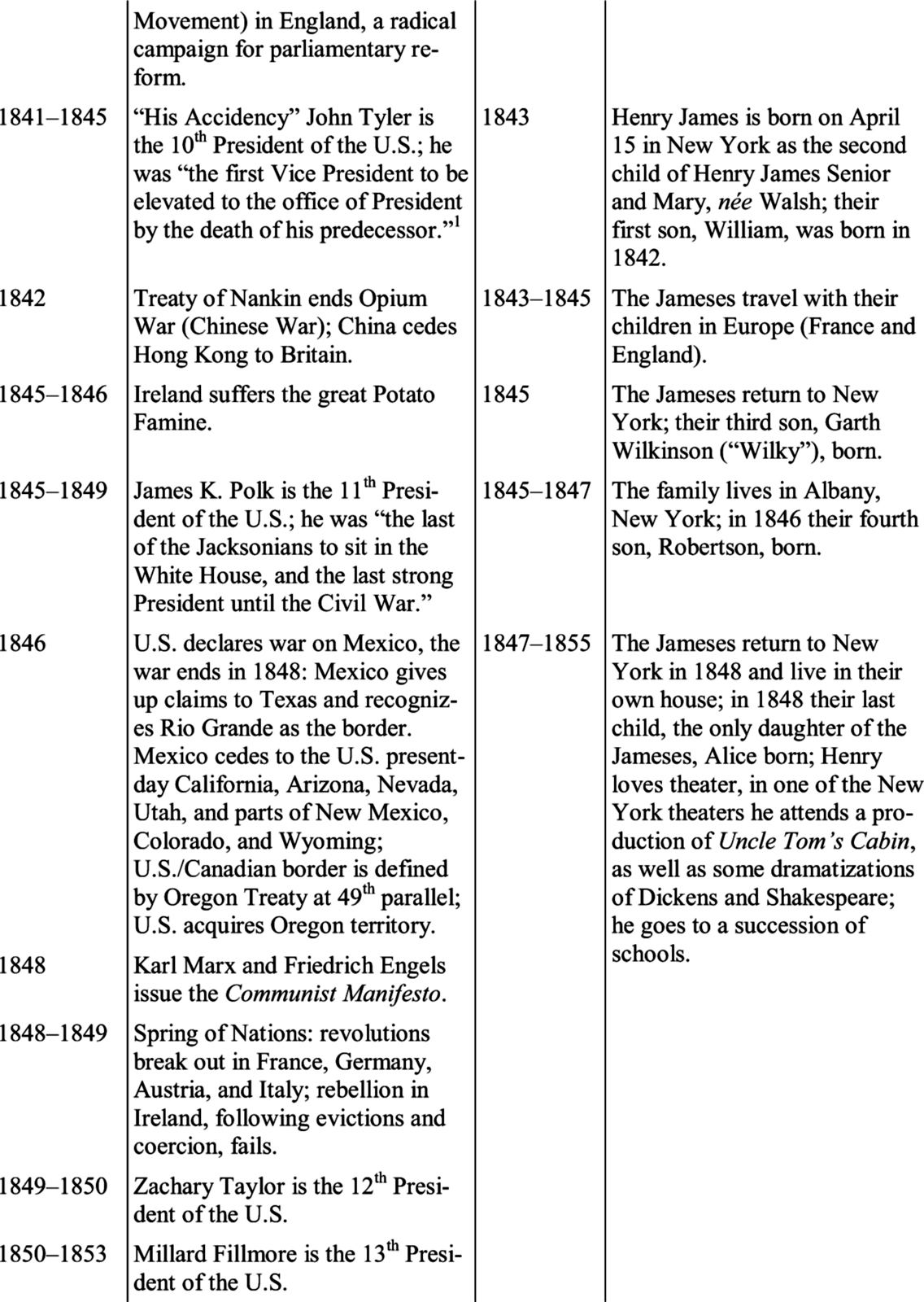

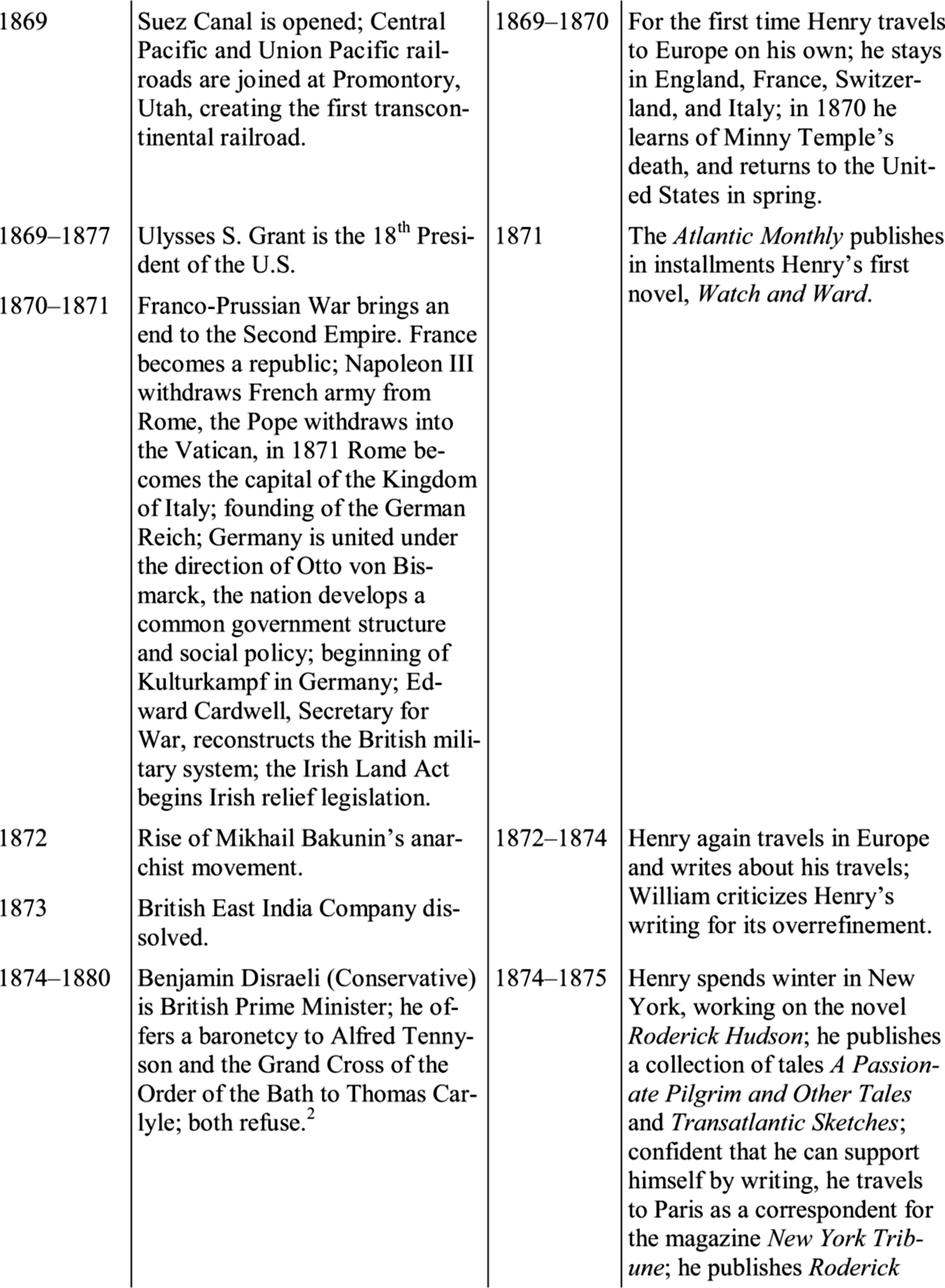

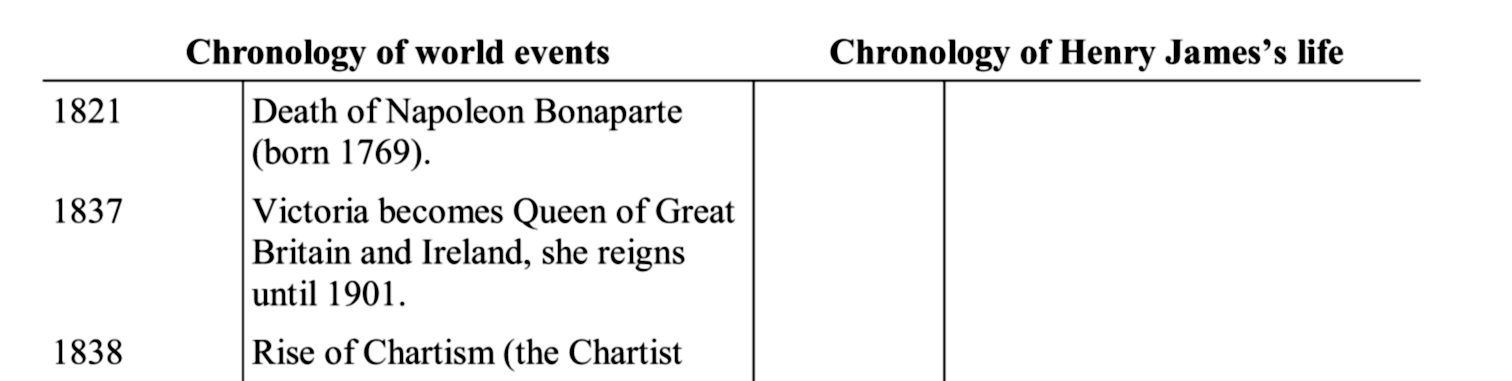

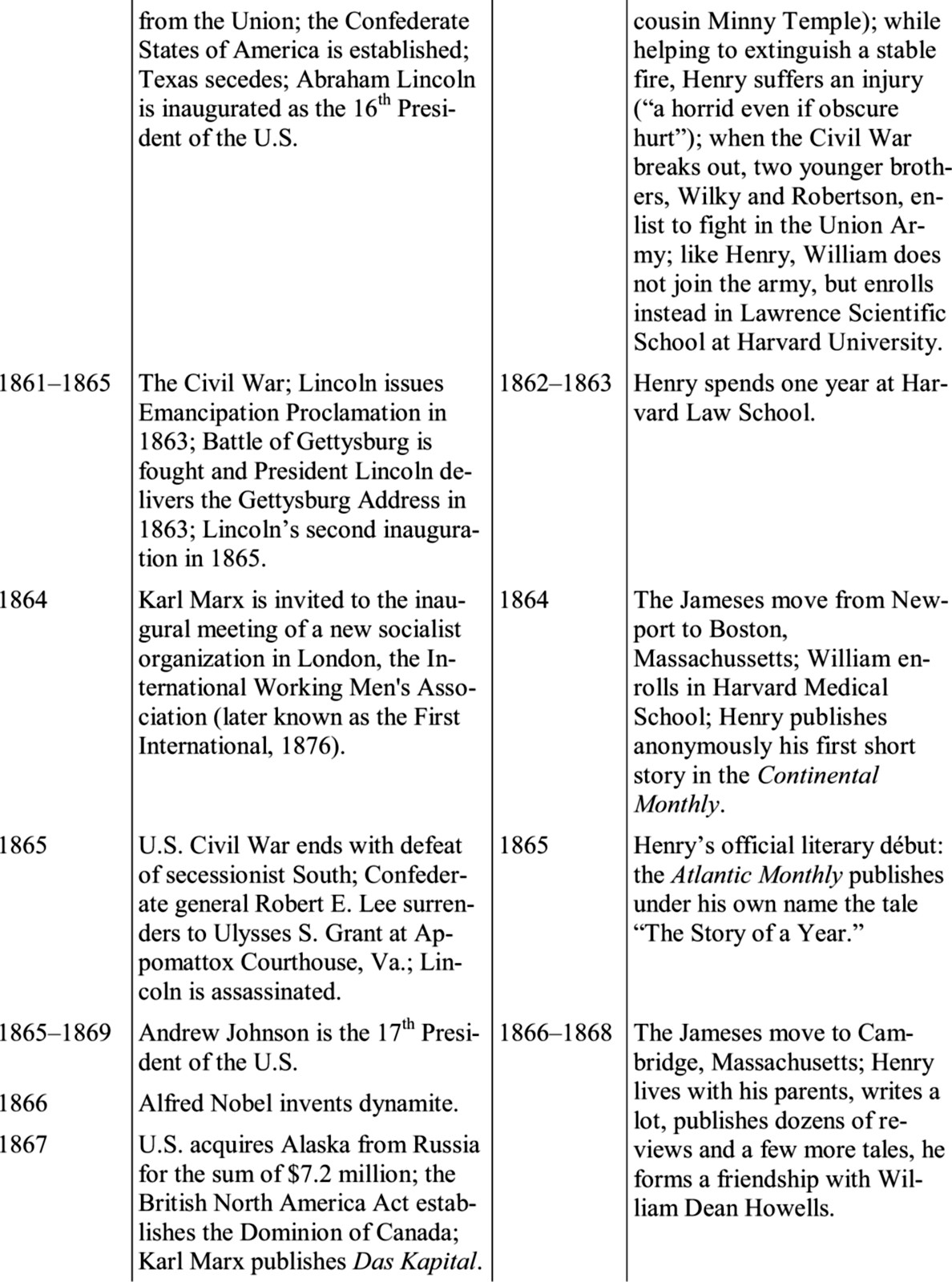

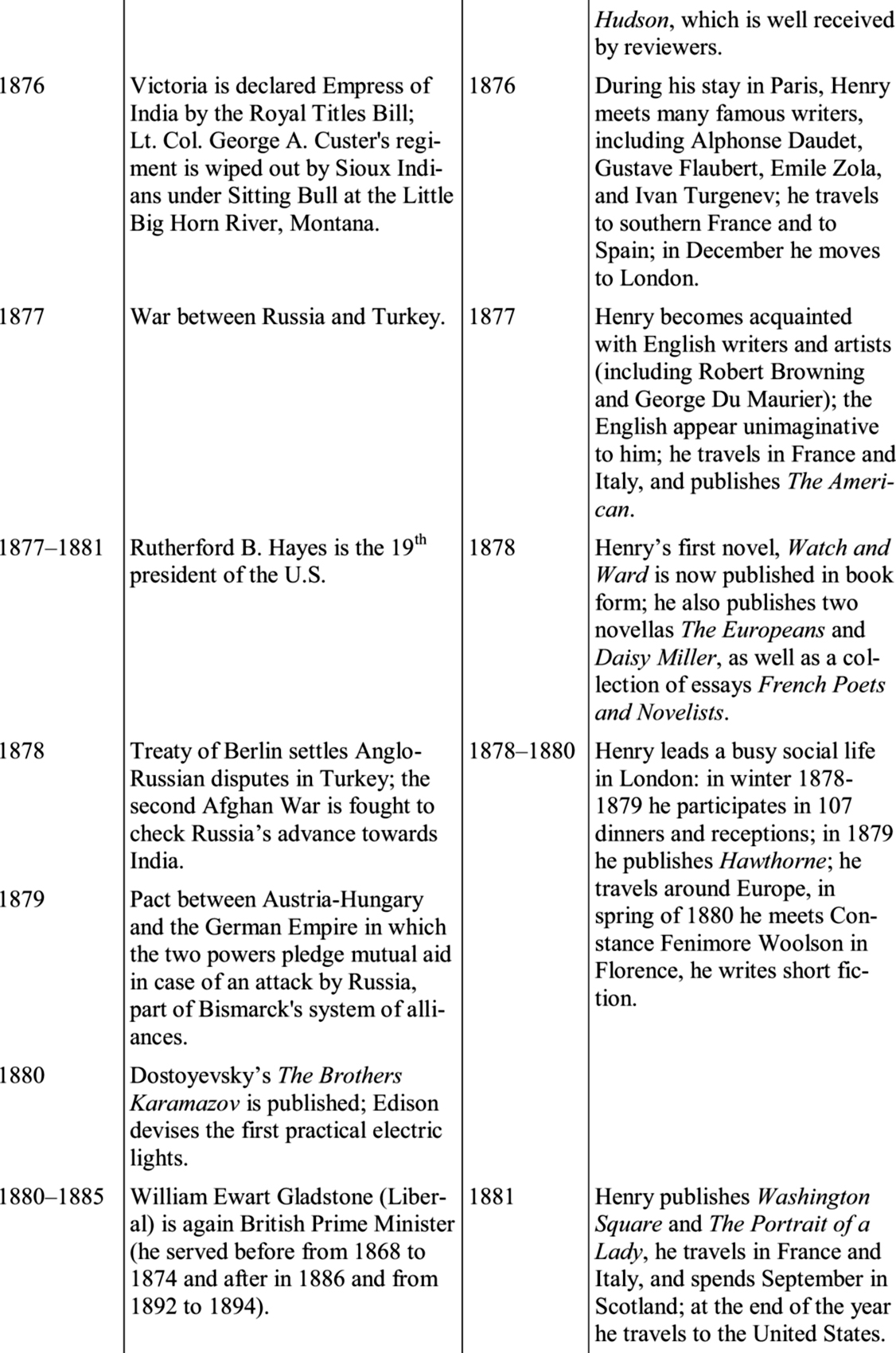

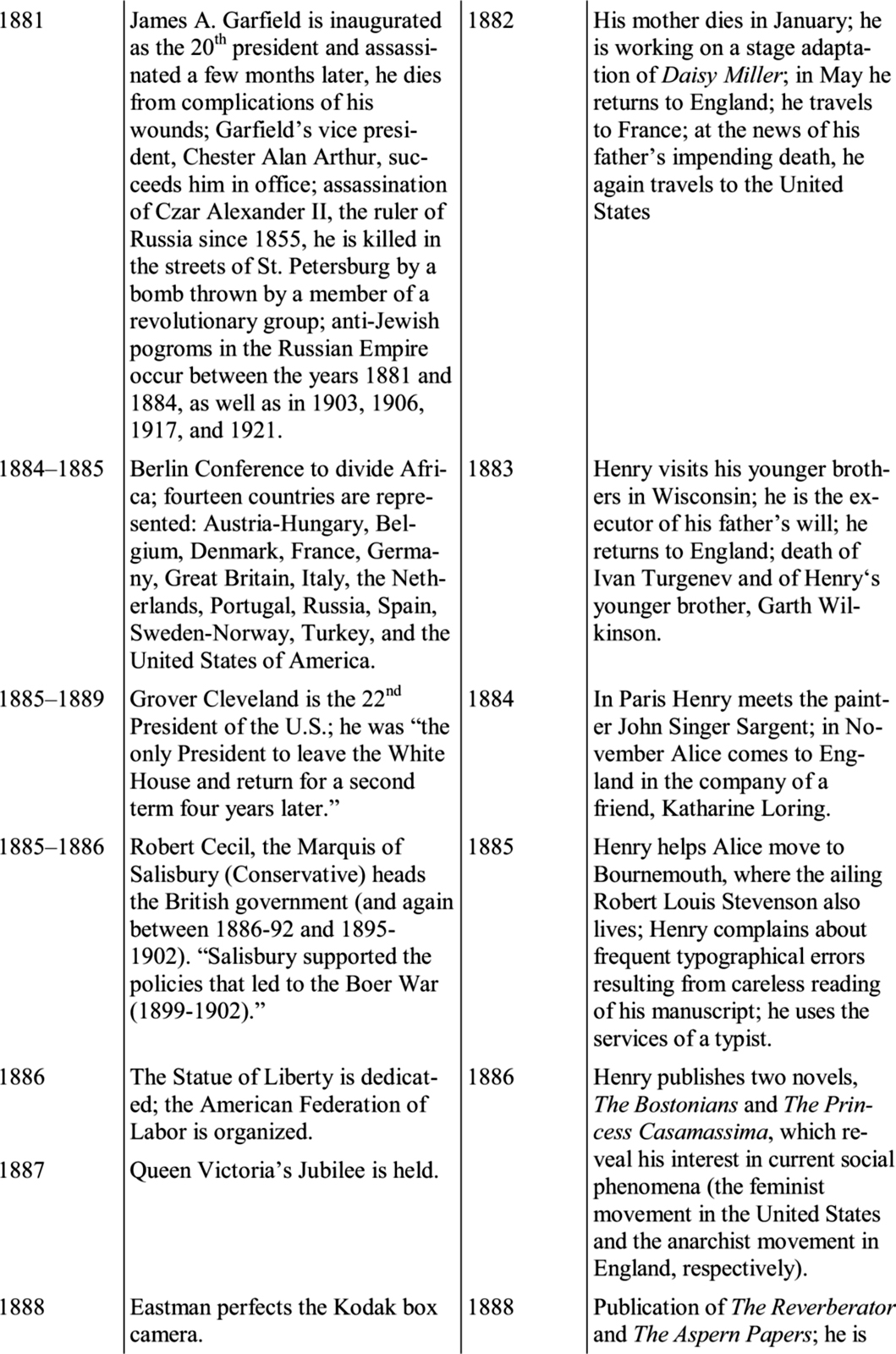

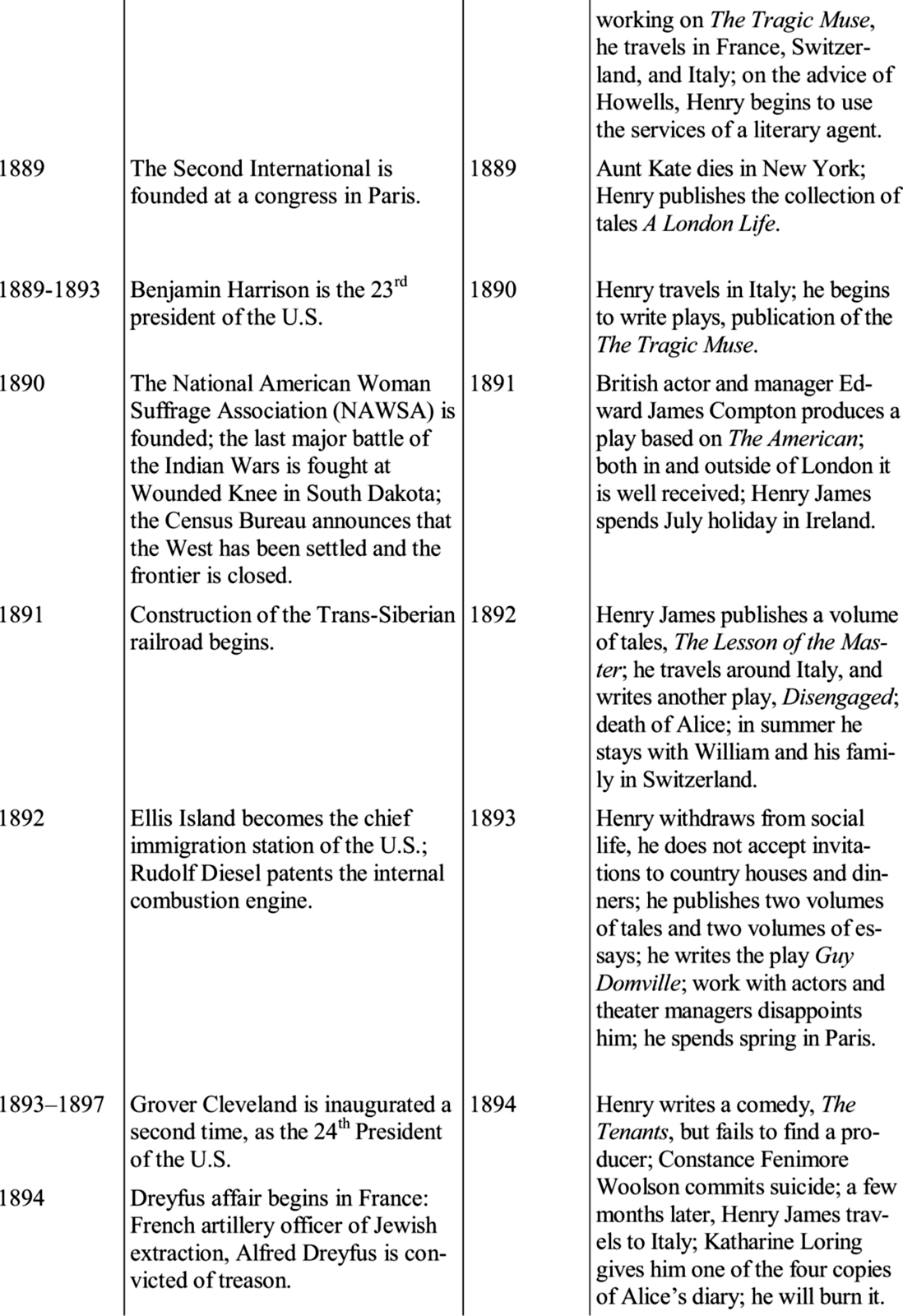

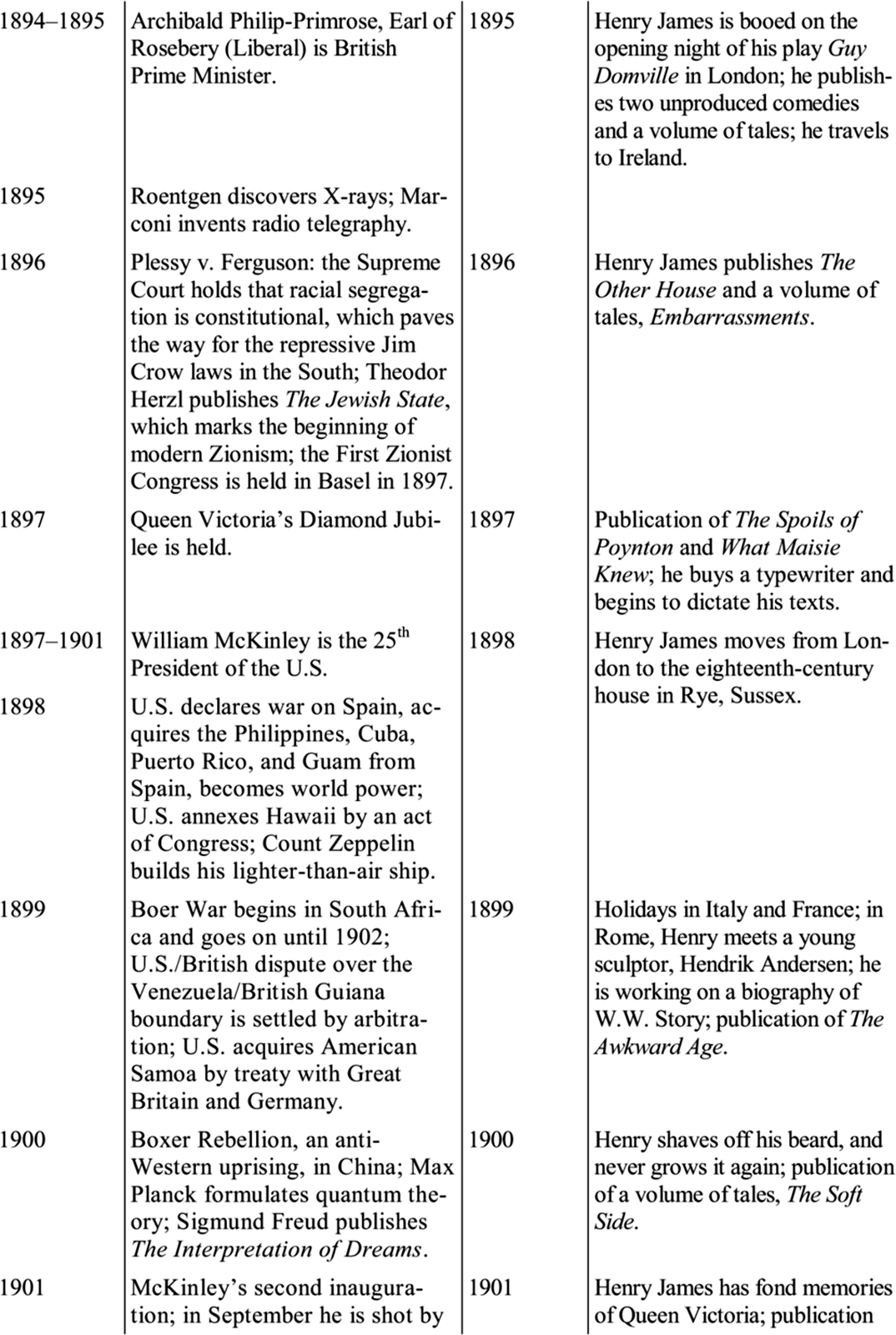

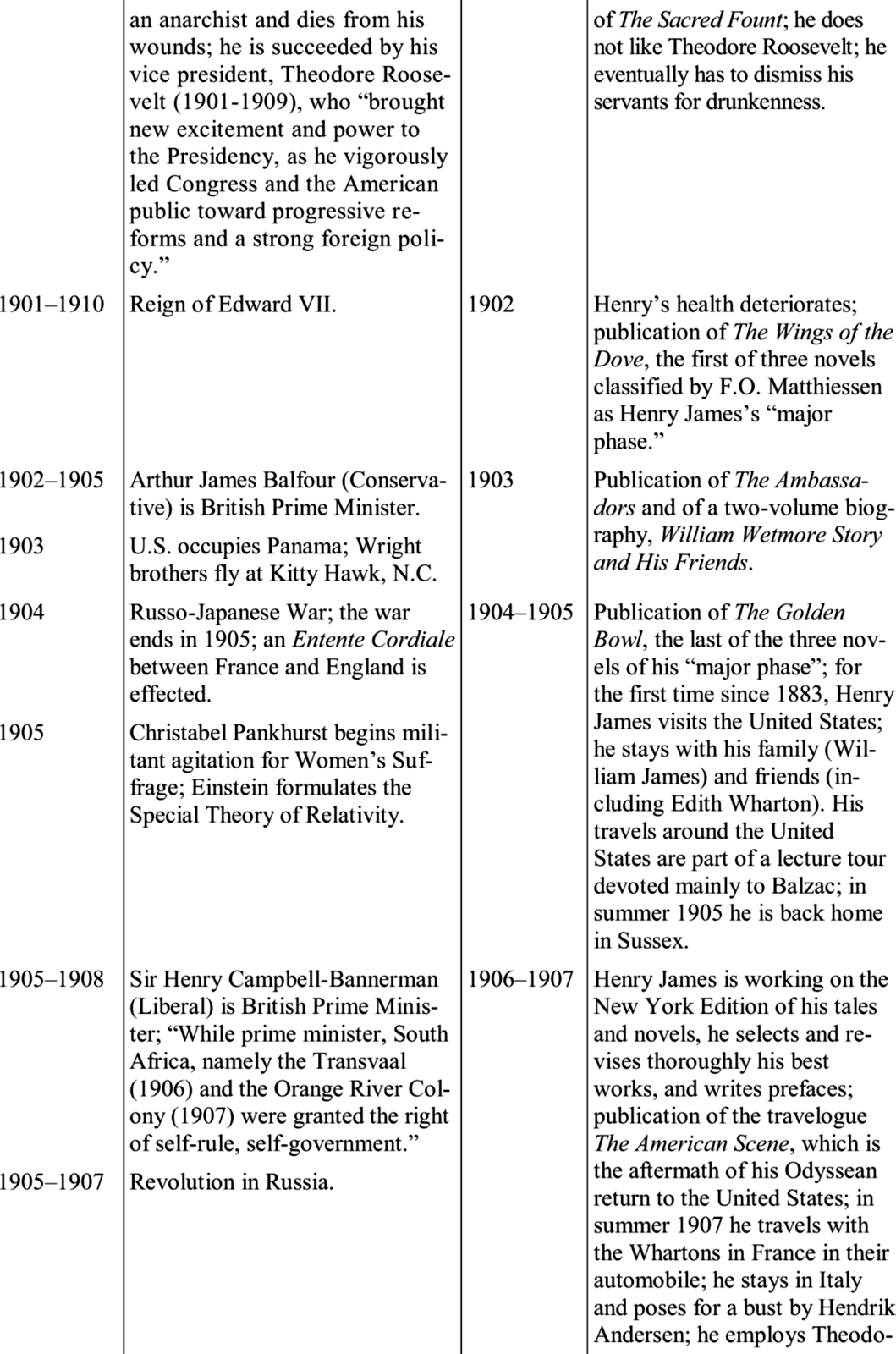

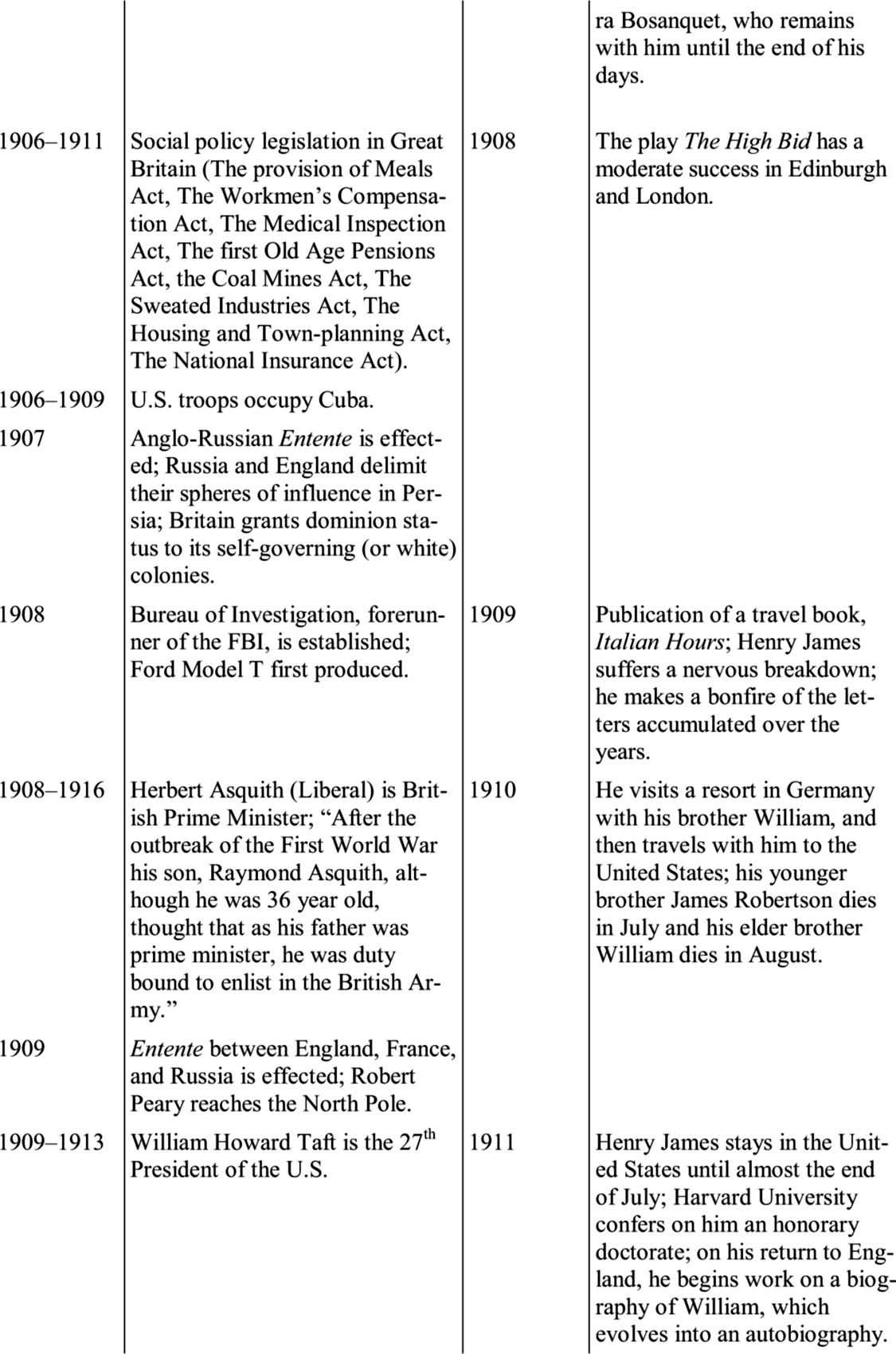

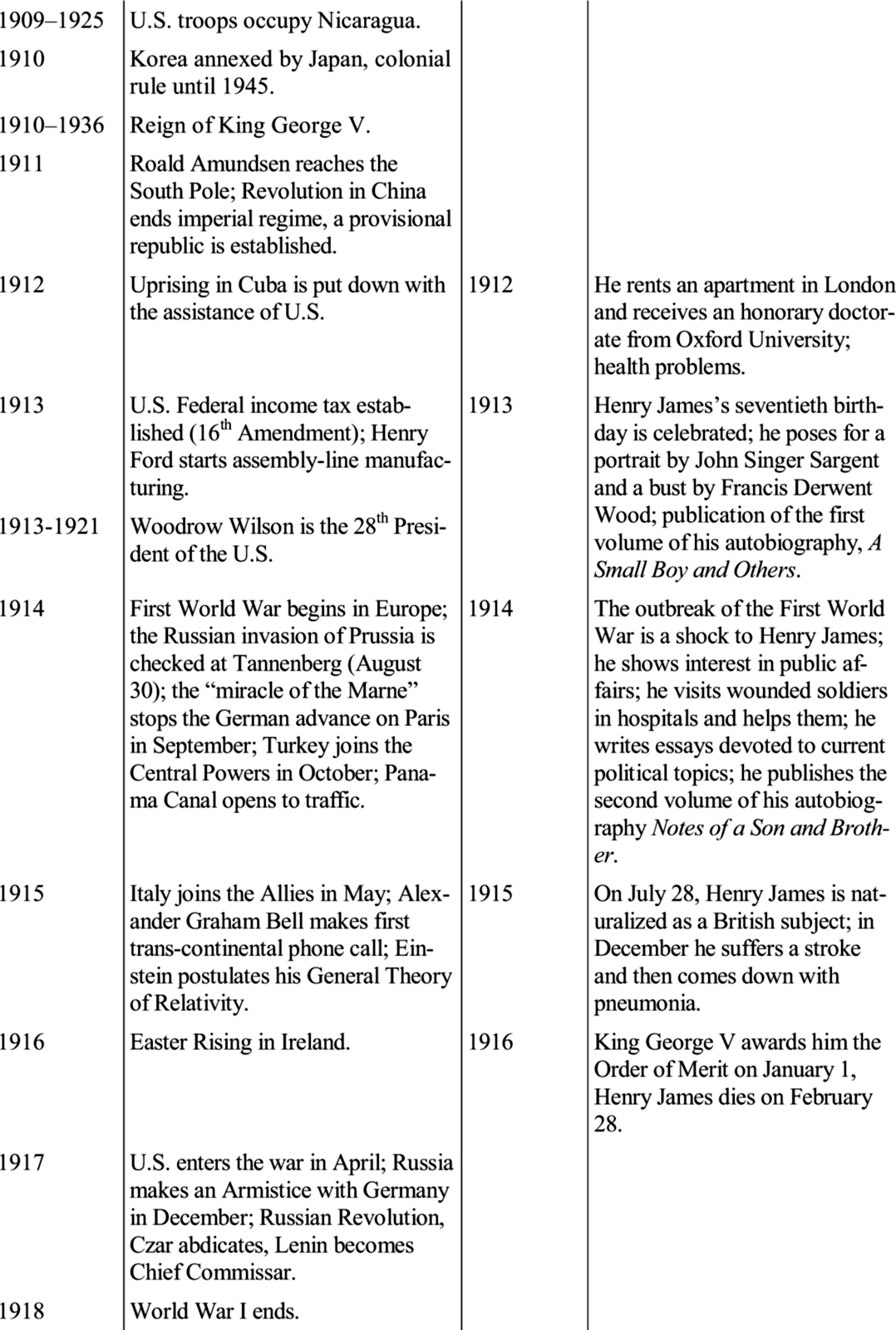

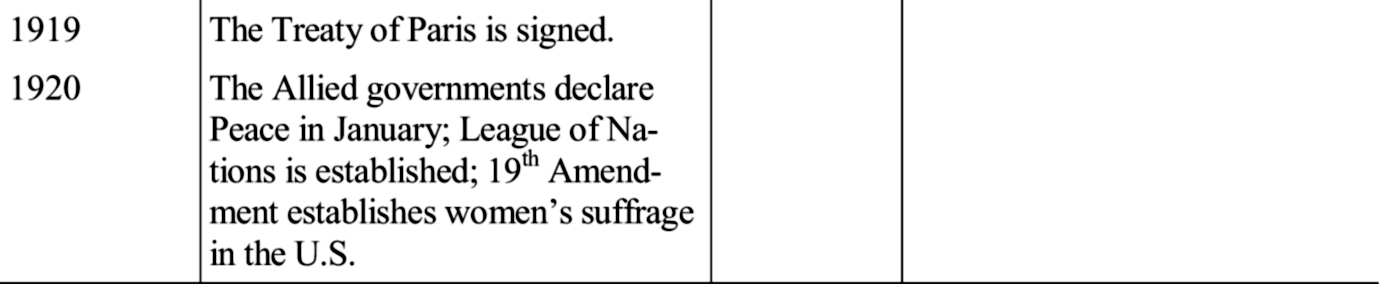

In the first paragraph of his book on Hawthorne, Henry James argues that “the flower of art blooms only where the soil is deep, […] it takes a great deal of history to produce a little literature, […] it needs a complex social machinery to set a writer in motion” (James 1966: 15). James’s argument may have applied to Hawthorne, who made much of the little he had access to by way of local history, but is it true of James himself? His output belongs to the most substantial in Anglo-American literary history, but was the soil on which his expatriate flower of art bloomed deep enough? It is only too tempting to declare him ahistorical and apolitical, or even draw the conclusion that he was unmanly and un-American, as Theodore Roosevelt or Maxwell D. Geismar did at different times and in different publications. Despite his lifelong fascination with the great Napoleon, James did not write historical fiction, and when he tried, the attempts were at best incomplete (The Sense of the Past), ineffective (“The Romance of Certain Old Clothes”), or else a downright fiasco (Guy Domville). With the exception of his two novels The Bostonians and Princess Casamassima, he hardly addressed large social conflicts affecting either America or Europe. He participated neither in the Civil War, which marked the beginning of his adult life and to which his two younger brothers so willingly marched off, nor in the Great War, whose end and outcome he did not live to see. The world he lived in abounded in major political conflicts, as the timeline below shows. James could not have remained entirely disinterested and unaffected. He knew people who waged wars, witnessed wars, participated and suffered in wars, and those who commiserated with their victims. Interestingly enough, some of James’s portraitists documented wars (Mathew Brady in his photographs of the Civil War, Fig. 2), commented on them in their art (John Singer Sargent’s Gassed, Fig. 3), or made masks for wounded soldiers (Francis Derwent Wood).

A great deal of history

← 9 | 10 →

← 10 | 11 →

← 11 | 12 →

← 13 | 14 →

← 14 | 15 →

← 15 | 16 →

← 16 | 17 →

← 17 | 18 →

← 18 | 19 →

← 19 | 20 →

← 20 | 21 →

A little literature

Within the past decades, the Master has been seen going to the movies3 and to Paris,4 both far more likely destinations for Henry James than battlefields of the modern world. Sending him off to war seems to be a preposterous idea, but the exaggeration inscribed in the title of our book is meant to stress the historicity of wars and battles underlying James’s life and work, quite apart from conflict on which literature thrives at all times.

The present volume consists of five parts devoted to various forms and aspects of conflict. Part One, “(Henry) Janus,” begins with Annick Duperray’s article which investigates various facets of Henry James’s life and work in relation with his conflictual relation to his native country – a factor which remains one of the irreducible complexities of his work. Why did Henry James actually return to the supposedly hackneyed theme of the American observer in his later years, even if he seemed to minimize its importance? Indeed, about novels like The Wings of the Dove or The Golden Bowl, he wrote: “the subject could in each case have been perfectly expressed, had all the persons concerned been only American, or only English or only Roman or whatever.” Greg W. Zacharias focuses on one source of struggle throughout Henry James’s life: a fundamental tension between work and friends. This tension can be read as itself questioning the boundaries of work and non-work lives. Memories of both his earliest reward as a professional writer, passages from the New York Edition prefaces, and a surprising section from The Middle Years both represent and linger on this struggle. James attempted to resolve this tension via his membership in the Reform Club and affiliation with liberal society in London. He was not entirely successful, though his struggle attending both to writing/work and to friends helps frame his deployment of the language of work and friendship in his fiction.

In the first article of Part Two, “The Civil War,” Joseph Kuhn looks at the moral and literary perplexity that runs through Henry James’s understanding of ← 21 | 22 → the Civil War and of the Confederacy. At first it seems apparent in The American Scene that James wishes to dismiss the historic enemy that was the South as a “grotesque, defeated project,” but at a deeper level in this work James seems, through a curious aesthetics of the wound, to identify himself with the unreconstructed South; he envisages the region in the “vivid and painful image” of an invalid in a wheelchair, querulously crying out a rhetoric of defiance. This figure comes uncomfortably close to James’s own account of his own ‘invalidism’ in the war: his avoidance of military action because of a “horrid if obscure hurt” that he received while putting out a fire. The article also addresses the complex Jamesian construction of Southern-ness in The Bostonians, and explores some of the inner divisions in James’s engagement with the recent history of a “blighted” South. Keiko Beppu seeks to answer the question of how Henry James was coming to terms with the Civil War and the South. She underlines the significance of the Civil War to the nation and personally to Henry James. If the War divided the “House,” it turned out to be a “house divided,” as it were, between the four James brothers: William and Henry vs. Wilkinson and Robert during the summer of 1863 and afterwards. Wilkinson enlisted in the 54th Regiment of all black soldiers led by Colonel Shaw, and later Robert joined the similar 55th Regiment. Among the wounded and the dead were relatives and friends of the James family. James and his friends visited the wounded soldiers sent back from the battlefields. James had to wait almost half a century to come to grips with his adolescent experience of the War going the round of his visits to the South in 1904–1905, with a copy of Du Bois’ The Soul of Black Folk (1903) as a guide. Ágnes Zsófia Kovács offers a careful reading of The American Scene, in which James, as she argues, not only criticizes the contemporary culture of the United States, but also formulates his sense of the American past. She addresses the question of how sites of memory connected to the American Civil War inform James’s experience and criticism of a turn-of-the-century American South, and shows that James’s experience-oriented reading of the South locates an absence both behind the sense of “The Old South” and behind the Southern memory of the Civil War. Kovács claims that for James the sense of the Old South as the Confederate cause for the war exists as a mere ghost only and stands in for very little in terms of material culture.

Part Three, “The First World War,” begins with Jacek Gutorow’s essay on Henry James’s sense of horror at the outbreak of the Great War (“this crash of our civilization,” “a nightmare from which there is no waking”). Almost at once James took active part in helping both soldiers and refugees from the Continent. He also wrote a few short texts in which he elaborated on his impressions. Gutorow studies “Within the Rim” and related texts, and comments on the perplexing blend of nostalgia (memories of the American Civil War) and ← 22 | 23 → aestheticization (“land and water and sky at their loveliest”) as well as James’s sense of being happily immersed in Britain’s splendid insularity opposed to the threat of the invisible. He finds those 1914–1915 essays ambivalent and problematic in their uneasy mixture of horror and sublime pleasures, active interest in war and passive contemplation of the summer sky and seascape. Katie Sommer offers a reading of four previously unpublished letters written to Henry James by active-duty soldiers during World War I. All four date from January or February 1915. The fact that James kept these four letters is noteworthy in itself. It is also noteworthy that World War I, such a seminal period in modern history, occupies such a small space in James studies, especially since it occupied a vast part of James’s emotional and physical energy in the last 18 months of his life. Nothing has been written so far about James’s personal involvement with the soldiers. Sommer’s article thus for the first time reveals the relationship between James and each soldier, which are, in turn, intimate, tender, fatherly, and friendly, and show the wealth of confidence they placed in James during the emotional, mental, and physical devastation of the Great War. Alicja Piechucka analyzes Henry James’s and T.S. Eliot’s responses to the First World War, as expressed in letters and The Waste Land, respectively. She argues that despite James’s view that the Great War was “too tragic for any words,” the two authors verbalized what they both saw – to borrow James’s phrase – as “a funeral pall of our murdered civilization.” Piechucka examines the parallels between James’s and Eliot’s visions of the First World War, striking despite their use of two different literary media, and suspended, as she demonstrates, between cultural and moral pessimism, on one hand, and determination to live in hope, on the other.

Details

- Pages

- 269

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631646014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653038637

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653994285

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653994292

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-03863-7

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (March)

- Keywords

- Postcolonialism World War One Sezessionskrieg American Civil War

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 269 pp., 10 b/w fig.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG