Theory and practice in sustainable planning and design

Planning, Design, Applications

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editor

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Contributors

- On the Sustainability of the National Architecture Movement Mosque Typology: Architect Kemalettin’s Mosques (Özge İslamoğlu and Aylin Aras)

- Scrutinizing the Relationship of Human and Place with the Concept of Place Attachment on the Axis of Historical Neighborhoods: Example of Amasya (Aslı Altanlar)

- Rural Landscape Planning in Turkey (Duygu Akyol, Doruk Görkem Özkan, and Demet Ülkü Gülpinar Sekban)

- Evaluation of Sustainability through Historic House Museums (Funda Kurak Açici)

- Sustainability of Architectural Heritage of Recent Era (Şengül Yalçinkaya)

- Evaluation of Hotel Buildings by Users within the Scope of Environmental Sustainability (Edirne) (Pınar Kisa Ovali, Hatice Kiran Çakir, and Damla Atik)

- Sustainable Campus Model Proposal to Kırklareli University’s Kayalı Campus (Fürüzan Çelik (Aslan) and Yaşar Menteş)

- An Analysis of the Interaction between Climate and City (Aziz Cumhur Kocalar and Pınar Kırkık Aydemir)

- Methodological Trial in Sustainable Architecture: Parasitic Architecture (Timur Kaprol)

- The Contribution of Green Infrastructure in Promoting Ecosystem Services in the Context of Urban Landscape (Oğuz Ateş)

- Rational Dimension of Assessing Landscape: Geodesign (Özlem Erdoğan)

- Cultural Significance of Historic Urban Landscapes and Evaluation of Conservation Problems: Case Study of Amasya-Hatuniye Quarter (Nehar Büyükbayraktar and Nilüfer Kart Aktaş)

- Ecological Trends in Landscape Architecture: Theory, Practice, and Application (Aysel Yavuz and Habibe Acar)

- Sustainability of Industrial Heritage: The Old Ice Factory Case (Soner Yeler)

- Learning through Place: Place-Based Design and Education Approaches in Architectural Design Studio (Gülcan Minsolmaz Yeler)

- On Bjarke Ingels’ Sustainable Architectural Approach (Aylin Aras and Özge İslamoğlu)

- The Effect of Increased Housing on the Neighborhood: Example of “Trabzon Kalkinma” (Makbulenur Bekar and Demet Ülkü Gülpinar Sekban)

- Urban Development Zones as a Risk Factor in Sustainable Urban Planning Process: An Evaluation for Balıkesir-Turkey (Serkan Sınmaz, Seher Erbey, Ahsen Özdemir )

- Investigation of Urban Tree Canopy as a Component of Green Infrastructure (Aylin Salici and Ahmet Alper Topaloğlu)

- Innovative Suggestions within the Context of the Sustainability of Architectural Cultural Heritage (Fulya Üstün Demirkaya)

- Green City as Smart Environment Strategy (Canan Cengiz and Aybüke Özge Boz)

- The Affordance Theory in Sustainable Open Space Design: The KTU Festival Area Case (Tuğba Düzenli, Emine Tarakçi1 Eren, and Elif Merve Alpak)

- Toward Eco-cities: Integrating Forms with Flows (Onur Güngör)

- Contemporary Analysis of Design Approaches in Historical Context: Transformation of an Industry Building into an Exhibition Building (Sennur Akansel)

- Understanding of Islamic Garden Culture in Andalusian Civilization: Case of Generalife, Alhambra, Spain (Hilal Kahveci and Parisa Göker)

- Islamkoy Traditional Houses and Building Materials (Sebnem Ertas Besir and Elif Sonmez)

- Urban Design Approaches to Prevent Vandalism and Crime (Özlem Candan Hergül and Gözde Sayin)

- Emotional Landscape Design through Kansei/Affective Engineering (Elif Karaca)

- Home-Making Process of Syrians through Sustainable and Flexible Reuse of Existing Building Interiors: The Sultanbeyli Case, Istanbul, Turkey (Özge Cordan and Talia Özcan Aktan)

- Traces of Local Identıty in Re-functioned Traditional Residences: Example of Şevket Demirel Museum House (Selver Koç Altuntaş and İrem Bekar)

- An Examination of the Industrial Structures of the Republic Period in Terms of Sustainability (Ali Mülayim)

- Design Model for Sustainable and Quality Neighborhoods (Mehmet İnceoğlu and Ahmad Walid Ayoobi)

- A Sustainable Approach to Urban Agriculture: Edible Landscape (Ayşen Çoban)

- The Evaluation of Planning Policies within the Context of Sustainable Development Principles in the Case of Tekirdag – Thrace (Hatice Meltem Gündoğdu and Mete Korhan Özkök)

- Sustainable Campus Planning: Suggestions for Sustainable Campus Design for Recep Tayyiip Erdogan University Fener Campus (Elif Şatiroğlu)

- The Place and Importance of Urban Squares in Terms of Landscape Architecture: Example of St. Mark’s Square, Venice, Italy (Aslı Gözde Gel and Elif Kaya Şahin)

- Edible Wild Plants in Trabzon and Consumption Form of These Plants (Elif Kaya Şahin and Aslı Gözde Gel)

- The Sustainable Planning for Cultural Heritage (İsmet Osmanoğlu)

- Evaluation of Re-functionalized Historical Structures in Terms of Social and Cultural Sustainability: Mihran Hanim Mansion (Ertan Varli)

- Positive and Negative Effects of Zoning Regulations and Plan Notes in Building Space Planning (Ezgi Ülker Bariş and Türker Keskin)

- Empathic Design Approach to Public Space Organization in the Urban Environment (H. Selma Çelikyay)

- Hospital Landscape Sustainability: Case Study in Turkey (Alev P. Gürbey and Nazlı Kanbur)

- Landscape Design for Autism Spectrum Disorder: Case Study of Niğde (Ahmet Benliay and Orhun Soydan)

- Shading and Cooling Role of Tree Canopies within Urban Forest Landscapes: Comfort and Recreation (Melih Öztürk and Lütfi Ağırtaş)

- Family-Friendly Planning as a Symbiotic Policy in Sustainability, Livability, and Quality of Life Interaction (Miray Gür)

- Re-functioning of Historical Buildings: “Kutahya Ahierbasan Street” (Berk Minez)

- Conservation of Cultural Landscapes in Historical Cities: The Case Study of Edirne Macedonia Tower and Archaeological Site (Beste Karakaya Aytin, Deniz Gözde Ertin, and Murat Özyavuz)

- Landscaping Strategies in Reducing Urban Heat Island Effects (Nilgun Guneroglu)

- Water Usage Patternks in Turkish Garden Culture Throughout History (Mahire Özçalik)

- Physical Planning in University Campuses: The Case Study for Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University (Reva Şermet, Murat Özyavuz, and Suat Çabuk)

Assist. Prof. Dr. Özge İslamoğlu

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Interior Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Aylin Aras

Bursa Technical University, Faculty of Architecture and Design, Architecture Department, Bursa, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Aslı Altanlar

Amasya University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Amasya, Turkey

Res. Asst. Duygu Akyol

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Doruk Görkem Özkan

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Res. Asst. Demet Ülkü Gülpinar Sekban

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Funda Kurak Açici

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Interior Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Şengül Yalçinkaya

Karadeniz Technical University, Architectural Faculty, Interior Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pınar Kısa Ovalı

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Edirne, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Hatice Kiran Çakir

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Edirne, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Damla Atik

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Edirne, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Fürüzan Çelik (Aslan)

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Landscape Architecture Department, Kırklareli, Turkey

M.Sc. Landscape Architect Yaşar Menteş

Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Agriculture and Forestry Provincial Directorate, Elazığ, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Aziz Cumhur Kocalar,

Niğde Ömer Halisdemir University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Niğde

Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Kırkık Aydemir Abant İzzet Baysal University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Bolu, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Timur Kaprol

Kirklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Kırklareli, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Oğuz Ateş

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Kırklareli, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Özlem Erdoğan

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Landscape Architecture Department, Kırklareli, Turkey

Research Assistant Nehar Büyükbayraktar

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Kırklareli, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nilüfer Kart Aktaş

İstanbul University-Cerrahpaşa Faculty of Forestry, Department of Landscape Architecture, İstanbul, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tuğba Düzenli

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Dr. Emine Tarakçi1 Eren

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elif Merve Alpak

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Aysel Yavuz

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Habibe Acar

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Soner Yeler

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Architecture Department, Kırklareli, Turkey

Assis. Prof. Dr. Gülcan Minsolmaz Yeler

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Architecture Department, Kırklareli, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Aylin Aras

Bursa Technical University, Faculty of Architecture and Design, Architecture Department, Bursa, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Makbulenur Bekar

Karadeniz Technical Kemal University, Faculty of Forestry and Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Demet Ülkü Gülpinar Sekban

Karadeniz Technical Kemal University, Faculty of Forestry and Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Serkan Sinmaz

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture

Seher Erbey

Yıldız Technical University, Graduate School of Science and Engineering

Ahsen Özdemir

Istanbul University, Graduate School of Social Sciences

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Aylin Salici

Hatay Mustafa Kemal University, Faculty of Architecture, Landscape Architecture Department, Hatay, Turkey

Res. Asst. Ahmet Alper Topaloğlu

Hatay Mustafa Kemal University, Faculty of Architecture, Landscape Architecture Department, Hatay, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Fulya Üstün Demirkaya

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Canan Cengiz

Bartın University, Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Design, Department of Landscape Architecture, Bartın, Turkey

Res. Asst. Aybüke Özge Boz

Bartın University, Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Design, Department of Landscape Architecture, Bartın, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Berk Minez

Trakya University Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Edirne, Turkey

Reva Şermet

Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University Faculty of Fine Arts, Design and Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tekirdağ, Turkey

Murat Özyavuz

Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University Faculty of Fine Arts, Design and Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tekirdağ, Turkey

Suat Çabuk

Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University Faculty of Fine Arts, Design and Architecture, Department of City and Regional Planning, Tekirdağ, Turkey

Mahire Özçalik

Kırıkkale University Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Landscape Architecture, Kırıkkale, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Nilgun Guneroglu

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Architecture Department, 61080, Trabzon, Turkey

Res. Asst. Selver Koç Altuntaş

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Interior Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Res. Asst. İrem Bekar

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Interior Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Asst. Prof. Dr. Ali Mülayim

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Kirklareli, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mehmet İnceoğlu

Eskisehir Technical University, Faculty of Architecture and Design, Department of Architecture, Eskisehir, Turkey

Ahmad Walid Ayoobi, PhD Student, Eskisehir Technical University, Graduate School of Sciences, Department of Architecture, Eskisehir, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Ayşen Çoban

Burdur Mehmet Akif Ersoy University, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Burdur, Turkey

Asst. Prof. Hatice Meltem Gündoğdu

Kırkareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Kirklareli, Turkey

R. A. Mete Korhan Özkök

Kırkareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Kirklareli, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Elif Şatiroğlu

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan Unıversıty, Faculty of Fine Arts Design and Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Rize, Turkey

Lecturer Aslı Gözde Gel

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Res. Ass. Elif Kaya Şahin

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. İsmet Osmanoğlu

Trakya Üniversity, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, 22100, Merkez, Edirne, Turkey

Lect. Dr. Ertan Varli

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Edirne, Turkey

Ezgi Ülker Bariş

Architect, Guest Lecturer, Namik Kemal University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Design and Architecture Department of Architecture, Suleymanpasa, Tekirdağ, Turkey.

Türker Keskin

Architect M.Sc., Guest Lecturer, Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Kırklareli, Turkey.

Prof. Dr. H. Selma Çelikyay

Bartın University, Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Design, Landscape Architecture Department, Bartın, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Alev P. Gürbey

İstanbul University-Cerrahpaşa, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Planning and Design Department, İstanbul, Turkey

Nazlı Kanbur, LA Assist.

Prof. Dr. Ahmet Benliay Akdeniz University, Faculty of Architecture, Landscape Architecture Department, Antalya, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Orhun Soydan

Niğde Ömer Halisdemir University, Faculty of Architecture, Landscape Architecture Department, Niğde, Turkey

Melih Öztürk

Bartın University, Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Design, Department of Landscape Architecture, Bartın, Turkey

Lütfi Ağırtaş

Bartın University, Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Design,Department of Landscape Architecture, Bartın, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Miray Gür

Bursa Uludag University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Bursa, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Özge Cordan

Istanbul Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department, of Interior Architecture, Istanbul, Turkey

Talia Özcan Aktan

Ozyegin University, Design, Technology and Society PhD Programme, Istanbul, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Elif Karaca

Çankırı Karatekin University, Kızılırmak Vocational High School, Department of Park and Garden Plants, Çankırı, Turkey

Res. Assist. Dr. Beste Karakaya Aytin

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Edirne, Turkey

Res. Assist. Deniz Gözde Ertin

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Edirne, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Özlem Candan Hergül

Bilecik Şeyh Edebali University, Faculty of Fine Arts and Design, Interior Architecture and Environmental Design Department, Bilecik, Turkey

Res. Assist. Gözde Sayin

Ankara University, Agricultural Faculty, Landscape Architecture Department, Ankara, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sebnem Ertas Besir

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Interior Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elif Sonmez Altınbas University, Faculty of Engineering and Natural Sciences, Interior Architecture and Environmental Design Department, İstanbul, Turkey

Asst. Prof. Dr. Hilal Kahveci

Bilecik Şeyh Edebali University, Fine Arts and Design Faculty, Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design, Bilecik, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Parisa Göker

Bilecik Şeyh Edebali University, Fine Arts and Design Faculty, Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design, Bilecik, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Sennur Akansel

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Architecture Department, Edirne, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Onur Güngör

İskenderun Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, İskenderun/Hatay, Turkey

←16 | 17→Özge İslamoğlu and Aylin Aras

Abstract: The National Architecture Movement is a style that took shape with the Turkish movement that developed under the influence of nationalist thought in the West in the 19th century, and was born as a reaction to the late Ottoman architecture that was under the influence of the West at that time. This style aimed to refine our understanding of architecture and with these principles it left traces in today’s Turkish towns. Kemalettin, the architect, (1870–1927) who was one of the pioneers of the movement, designed many buildings that reflect the first national architecture period. Mosque structures were especially in the foreground among the structures that were built within the style of the period. These structures represent private areas that reflect the social, cultural and economic structure; lifestyle and philosophy of the periods they belong to; urban memory; and are important witnesses of past cultures and periods. Sustainability of these structures should be ensured by protecting them with their unique plan schemes, decorations and construction techniques.

In this context, the study includes the architectural analysis of the mosques designed by Architect Kemalettin Bey, who is one of the pioneers of the First National Architecture style, with his unique characteristic structure. The aim of the study is to read the national architectural movement mosque typology through the Architect Kemalettin’s mosques and to contribute to the documenting, preservation and thus the sustainability of the mosque typology, which has its own characteristics. Depending on the fact that Kemalettin Bey was the pioneer of the period, the mosques under study are thought to have the quality to give information about the period.

Keywords: The National Architecture Movement, mosque typology, Architect Kemalettin

1. Introduction

Period structures are important elements of our cultural heritage with their social, economic, cultural and physical values. These structures are with documentary values that reflect the historical development of the countries in all its stages. Therefore, transferring these structures to future generations is important in terms of ensuring the urban identity and continuity of culture, because the concept of sustainability, which aims for countries to exist in the next centuries, cares about defining structures with their social and cultural dimensions and ←17 | 18→emphasizes the sustainability of the heritage. Based on this, within the scope of the study, the national architectural movement and the mosque structures of Architect Kemalettin, which is the first modernization effort in the history of Turkish architecture, are discussed.

Political, social and cultural changes that took place in the Ottoman Empire together with the Tanzimat Period have influenced architecture as well. Architects in this period tried to create the Turkish national style by using elements of the classical Turkish architecture. In this study, the national architecture movement, described as the first modernization effort in the history of Turkish architecture, and the mosques of Kemalettin the architect, who pioneered this movement, are discussed. Based on the thought that the style has its own principles and architects of the period would reflect these principles, the aim is to focus on Kemalettin the architect’s mosques in order to obtain information on mosque architecture of that period. The study is thought to be significant as it is thought to have archival value in terms of bearing information on mosque architecture of that period. The reason that mosque structures were selected was because it is especially significant to know how a style that has Islamic underlying elements influenced religious structures.

It is considered to be important for sustainability that the study is an archive that gives information about the mosque architecture of the period. The reason for choosing mosque structures is that it is of particular importance that a style with Islamic elements at its core influences religious structures. With this aim the study is split into two parts. The first part contains the theoretical information concerning the political and social structure, architectural circumstances and Kemalettin Bey’s life in the years covering the first national architecture period. The second part contains the spatial analyses of the selected mosques. In this context, the mosques that have been included in the study are the following ones, as they best reflect Kemalettin Bey’s understanding of national architecture and are the ones that best adapt to the classical age Ottoman architecture [1];: Bostancı Kuloğlu, Bebek Kamer Hatun, Yeşilköy Mecidiye and Amine Hatun mosques. The analyses were carried out by examining the selected mosques regarding location, mass characteristics and facade setups of mosques. In this way, the aim is to obtain the general characteristics. In the next stage, the study was concluded by making evaluations.

2. First National Architecture Movement

The First National Architecture Movement is a style that is known with many other designations such as “The First National Style”, “National Architecture ←18 | 19→Renaissance”, “New-Ottoman”, “New Classical Style”, “Neo-Classical (Turkish) Style”, and “Ottoman Revival” [2–7]. The reason that the title “national architecture period” is used within the scope of this study is because it is the most inclusive and most common designation. This style, which developed in the last years of the Ottoman Empire and continued to have an influence in the first 10 years of the Republican Period, thus being effective between the years 1908 and 1930 in Turkish architecture, covers a period of 20 years that started with the declaration of the Second Constitutional Era and ended in the 1930s [3, 6]. Although this movement is a style that started in the era of the Ottoman Empire, it made its actual impact during the time of the Turkish Republic [7].

In the 19th century, Turkey started to be socially differentiated and architecture entered into a requirements change [8]. The nationalistic movements seen in the West in the 19th century spread to the Ottoman lands as well, and after the Second Constitutional Era the Ottomanist mindset gave way to neo-Turkism [9]. This period happened to be the time when the Ottoman Empire collapsed and the Turkish Republic was founded, and a time when nationalist thought was dominant in the country and the thoughts developed in this context in time exercised influence over architecture as well. Therefore, it was Turkish nationalism that shaped the national architecture movement. This style can be interpreted as the reflection of the nationalism that emerged with the declaration of the Second Constitution in 1908 to the field of architecture.

Loss of land and continued decline of state authority during the years of the First World War led to a search for a solution among Ottoman intellectuals, and as a result a nation-centred approach was pursued [10, 11]. Contrary to rejecting the West, a nationalism that aimed at Westernization, namely modernization, but also at the same time one that resisted Western exploitation was searched for by being called national defence, national economy, national industry and national saving in the political sphere; and being searched for in many areas it found its reflections in architecture as well. In the light of this nationalist policy, the construction of buildings influenced by the West in these years began to be criticized, and thinkers like Ziya Gökalp spreading Turkish nationalist thought raised the topic of a new architecture in this regard [6]. At that period, nationality replaced religion as the primary indicator of identity, and elements borrowed from classical Ottoman architecture (namely, Turkish culture: According to Ziya Gökalp, the source of national culture is not the culture of the Ottoman sultans but the culture of the Turkish people) were fused with the academic design principles and construction techniques of Europe (namely the Western civilization) [5].

Two architects that pioneered the first architecture movement and enabled it to develop were Kemalettin and Vedat. These two architects completed their ←19 | 20→education in Europe and returned to the country, attempting to execute a new style. In that period the Turkish ideology, which was the product of nationalism prevalent in Europe and influential in Ottoman politics as well, produced the national architecture style in which Turkish-Islamic Architecture was revived. The efforts of the two pioneers of the style to form an ideal Turkish architecture was compatible with the dominant political mindset of the time, and this resulted in the spreading of the style in a short time. Architects who aimed to form a Turkish architecture by avoiding foreign influences perpetuated this style from the declaration of the constitution until the first periods of the republic. The movement which started in Ankara, İstanbul and İzmir started to spread to other cities as well with the support of the government, and state buildings were constructed with respect to this movement. Also, in this period there was demand for a law that would force private individuals to construct buildings in accordance with this style [12]. With these circumstances, a brand new period in Ottoman architecture commenced in the 20th century.

2.1. General Architectural Features of the First National Architecture Movement

The first national architecture movement was seen as too stylized, Westernized and modernized, distant from tradition to be included in the Ottoman tradition by Ottoman and Islam architecture historians, and for Turkish architecture historians it was the alternate that had to be left behind in order to catch the spirit of the modern age [5]. In these years, architects endeavoured to create a new architectural identity by experimenting with new building types, construction techniques and design methods for the first time. Architects stylized Westernized forms with references that they made by not detaching themselves from Ottoman Islam Architecture altogether. In this process, Westernization movements taking place in the Ottoman geography influenced architectural structures as well; and architectural motives of Western architectural works such as Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque were used in combination with Islamic elements [13]. Even though this style is interpreted as a style that strives for modernization but in fact straddles as a result of not being able to sever itself from Ottoman Islamic architecture, it is also seen as the first modernization effort in the history of Turkish architecture.

The vagueness that emerged with regard to the interpretation of the first national architecture movement – the vagueness of a style that incorporates modern functions and at the same time makes references to the Ottoman-Islam past – rendered it open to many different readings and interpretations that varied ←20 | 21→over time. Ottoman artists and architects evaluated this style as the heritage of the Ottoman, while for Turkish nationalists and early republican followers it was the Turkish national style. According to Turkish nationalists and republicans, it was argued that Ottoman form and motives used in the buildings were not peculiar to religion or Ottoman culture but instead to Turkish culture itself. In these years Ottomanism gave place to Turkish nationalism ideology together with the First World War, and as a result increasingly more Turkishness was included to Ottoman forms symbolically. Especially Young Turkish architects, who received education from Vedat Bey, Kemalettin Bey and Guilio Mongeri, adopted the Turkish nationalist style. These architects saw the Turkish nation as the nucleus of the society. In the year 1918, Ottoman revivalism in Ottoman architecture undoubtedly began to mean Turkish national style [5].

In the first national architecture works Ottoman or Seljuk coves, marble columns, chequered, stalactite capitals, tile panels and metallic decorations were used, especially entrances of facades were given importance to and domes with no spatial correspondent underneath were emphasized. However, in spatial construct, high medium spaces covered with glass on top, that are not found in Ottoman, and are seen in large banks and similar structures in Europe, were used [11]. The representatives of this so-called movement tried to apply to civil architecture elements such as wide starboards, domes, lancet arches, columns, corbels, stalactite capitals and tile coatings which they borrowed mostly from older religious structures. The movement was mostly seen in public buildings; it did not have much of an effect on residences [7].

In its most general expression this style supported the ideology of the years it covered, thus configuring in a modern way lancet arches, domed and steeple towers, wide starboards, tiles, etc. of Turkish-Islamic architecture, and used them again by incorporating them into Western style structures [5]. When we look at structures built in this period, instead of searching for a new plan, architects gave more importance to facade arrangement and ornamentation program [6]. National architecture movement is an architectural discourse in which Western contemporary techniques are used together, which for some it is a blending [5]; for some it is a contradiction [6]; for some researchers it is far from responding to the requirements of the era, as well as being eclectic, formative and sentimental [12]; according to some it is a synthesis concerning form by not being spatial [7]; and according to some it is eclectic Ottoman revivalism [11]. Shortly, as the most general expression of national architecture style, it is possible to say that it is the effort to bring together elements taken from Ottoman architecture and new construction techniques.

←21 | 22→The collapse of the National Architecture Renaissance, that was shaped in this way, started around 1927 and it was completed in 1931. In these years, pertaining to Western-oriented and secular cultural politics, references to Ottoman architecture were left behind for Republican architects [5], buildings enacted with the use of Ottoman revivalism came to a complete halt and at the start of the 1930s First National Architecture gave way to simple but functional modern architecture.

2.2. Kemalettin the Architect

Kemalettin the architect, who combined old Turkish style with new requirements, is one of the most important names of the national architecture movement. His real name was Ahmet Kemalettin and he was born in Istanbul in 1870. He graduated from the school of engineering in 1891 but he did not practise engineering because of his interest in art and architecture. Kemalettin was sent to Istanbul to inspect Turkish architecture by the German government in those years and was appointed as Assistant to professor of architecture, Jasmond. In the year 1895 with the support of his teacher Kemalettin was sent to Germany to complete his education, then he returned to the country appointed as architecture and building. Kemalettin remained loyal to the national art with what he learned from the school of engineering and in Germany. The most fruitful period of Kemalettin Bey in terms of architecture is the ten-year period between 1909 and 1919. In the year 1909 he was appointed as head of Evkaf Nezareti (General Directorate of Foundations); the directorate was maintained to work in the form of a large architecture and construction bureau [3, 7, 14, 15].

Some important works of Kemalettin Bey that have endured to our present day are as follows: Bebek Mosque (İstanbul, 1913), Bostancı Kuloğlu Mosque (İstanbul, 1913) and Bakırköy Kartaltepe Mosque (İstanbul, 1923–24), Sultan V. Mehmed Reşid Türbesi (İstanbul Eyüp, 1910–12), IV. Vakıf Hanı (İstanbul Bahçekapı, 1916–26), Edirne Karaağaç Train Terminal (1913–14, Trakya University Rectorate) and Ankara Palace, which was left unfinished by Vedat Tek [16].

As a result of the cerebral haemorrhage he had in Ankara in 1927 Kemalettin died and the first national architecture period closed; after this, the Turkish architecture of the period was dominated by an international design sensibility under the influence of foreign architecture teachers from abroad [17].

3. Analyses from Kemalettin the Architect Mosques

3.1. Method

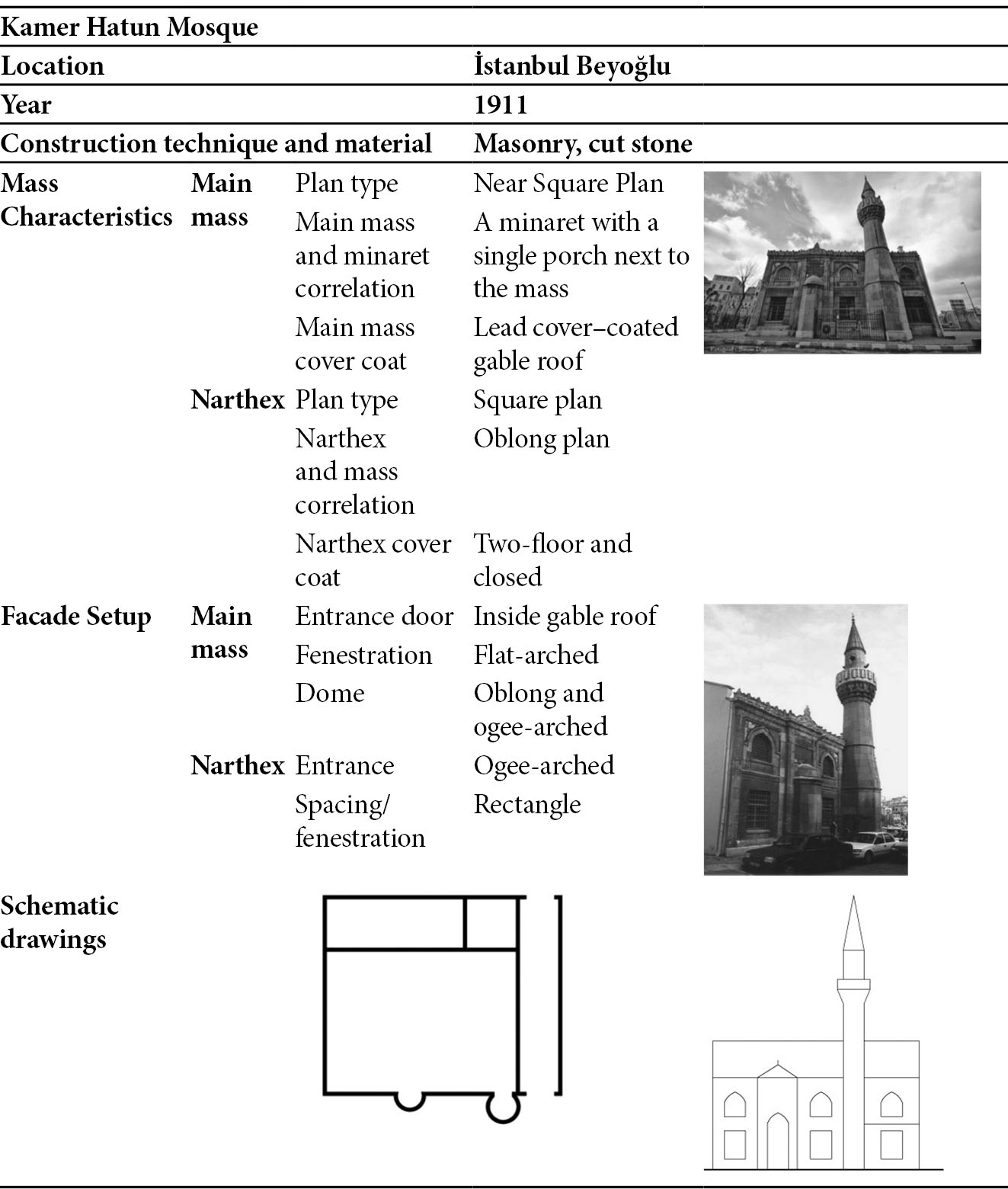

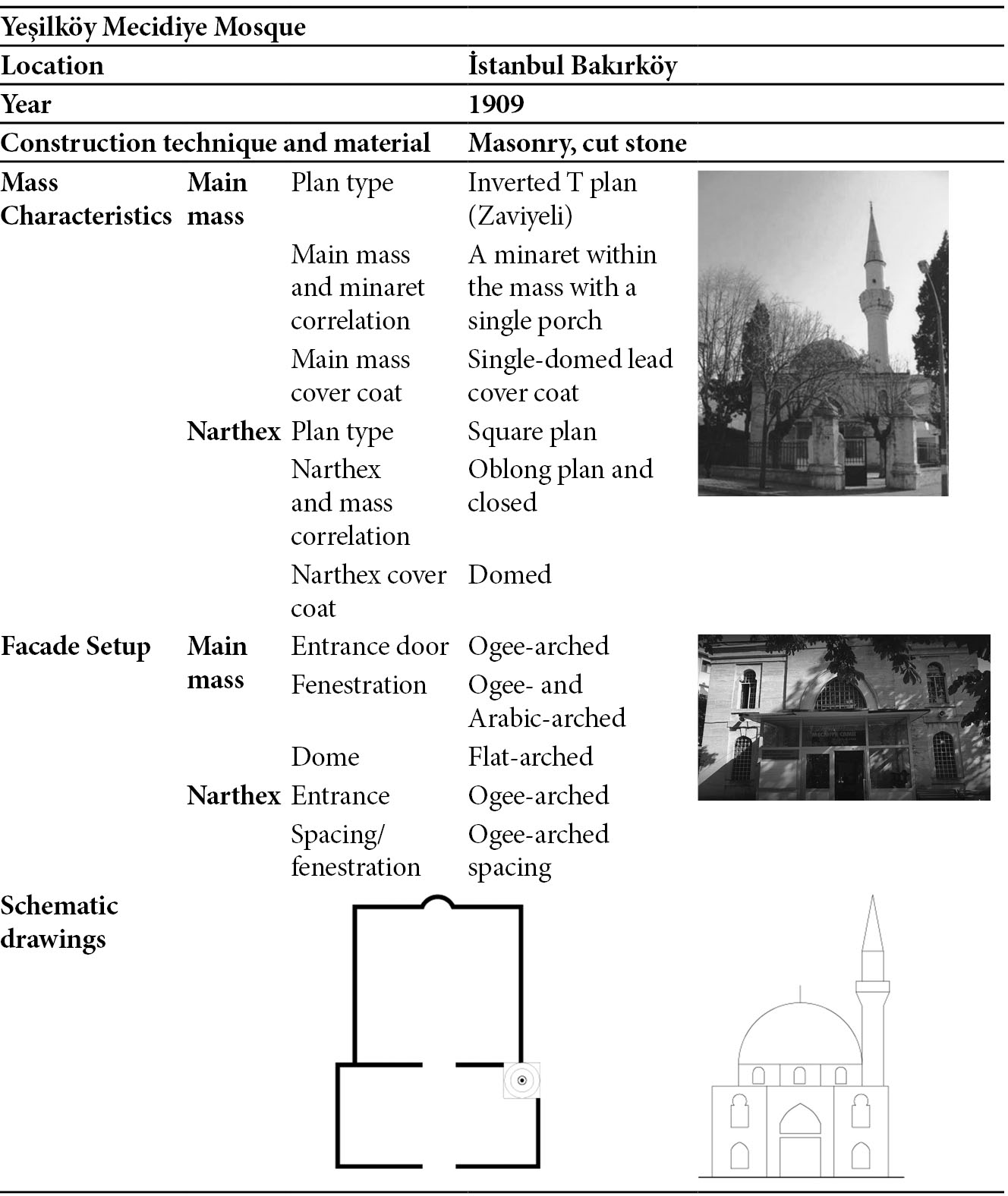

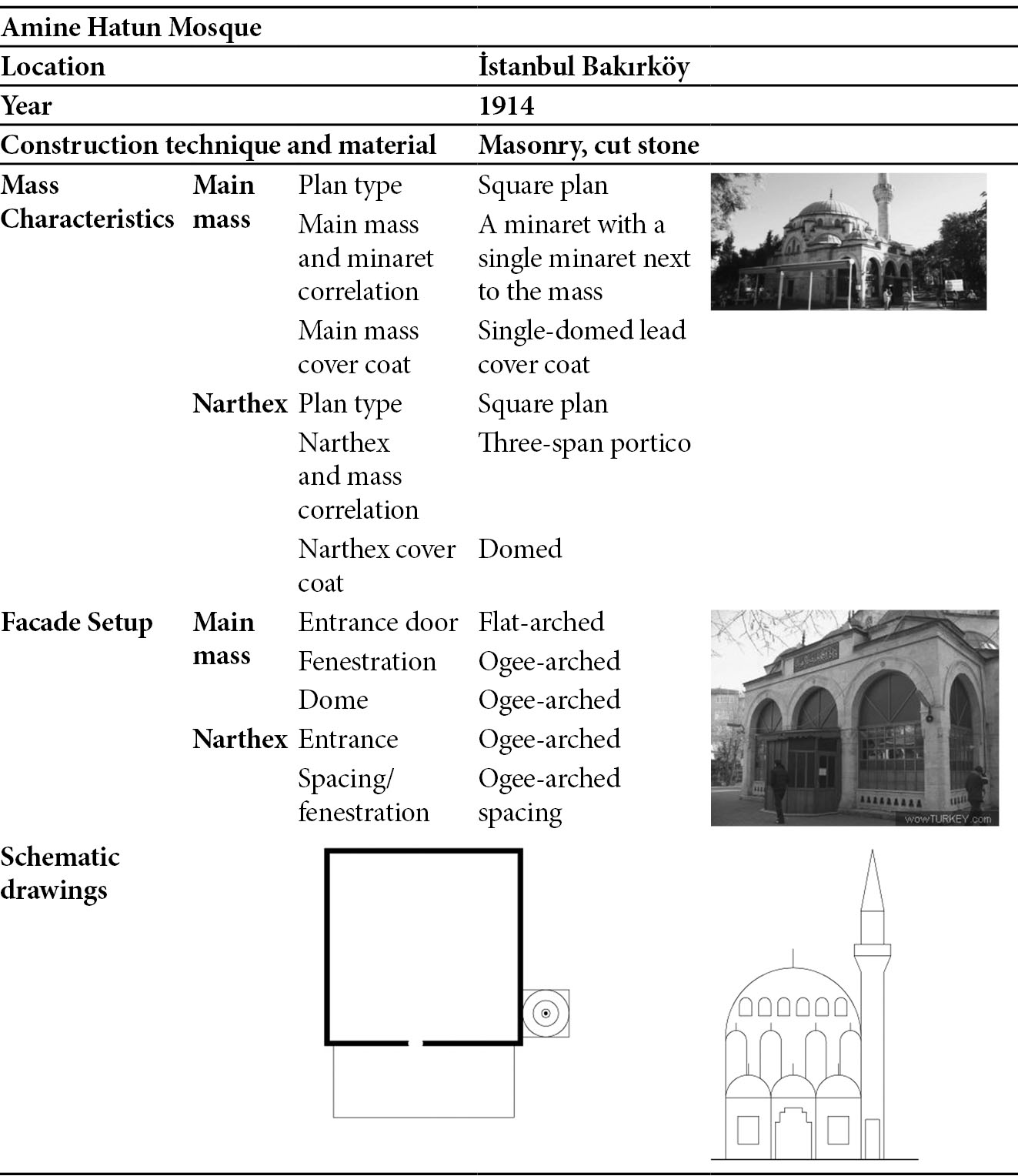

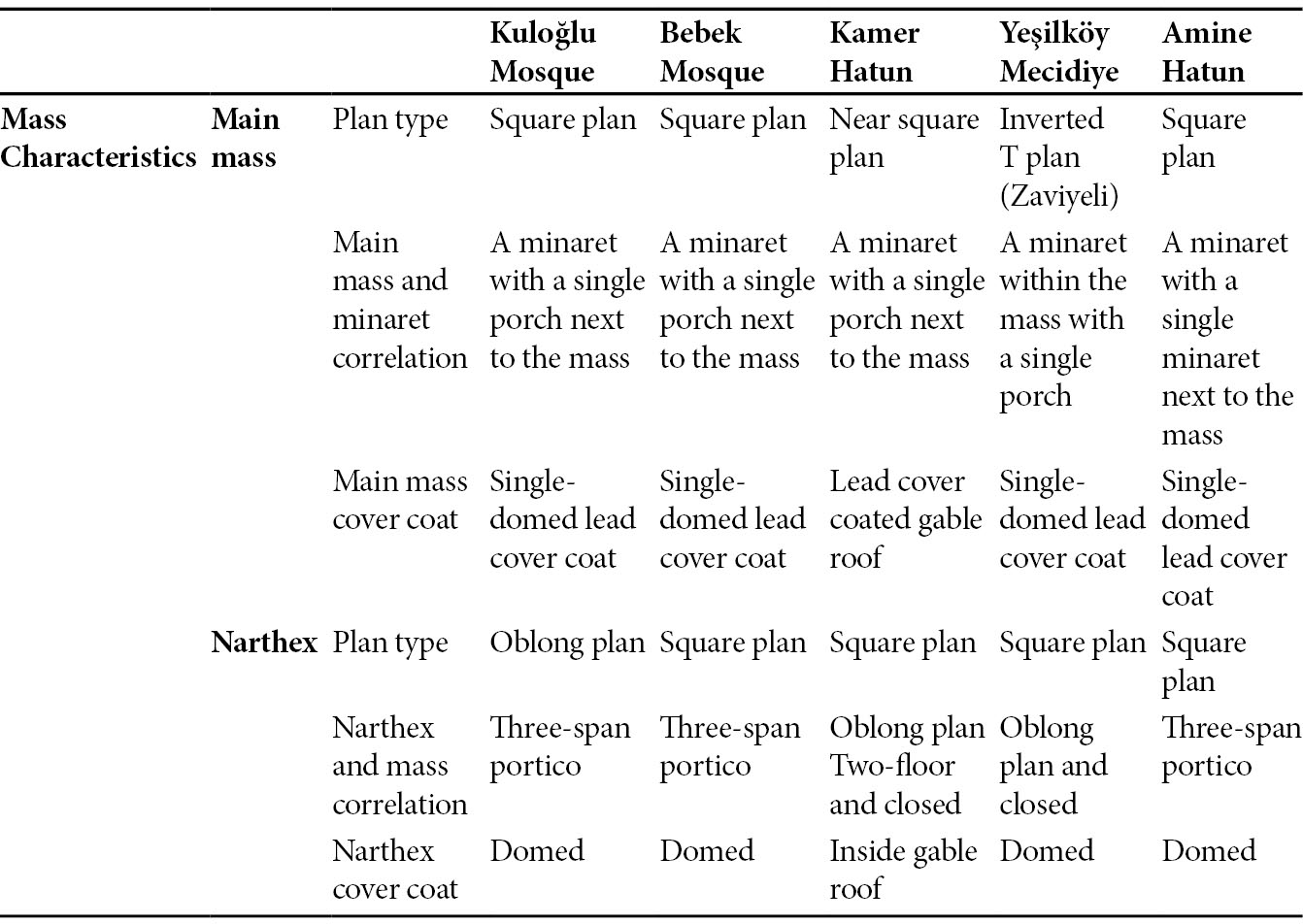

This study aims to obtain information about the national architecture period’s religious structures by analysing them with the spatial analysis method. The work was ←22 | 23→prepared in order to achieve this end and was organized into two parts. First, books, articles, newspaper articles and theses were found and the literature was searched. In the literature study performed, it was understood that Kemalettin the architect had designed mosques primarily in Istanbul, and also in Bandırma, Isparta, Geyve, Konya, Samsun, Aydın and Ankara, but some of these were not constructed and remained as designs. Additionally, it is common knowledge that Kemalettin the architect had carried out the rebuilding projects of some mosques that were originally built by other architects and were demolished. As for the scope of this study, five mosques, built within Istanbul boundaries and that best reflect the characteristics of this period, are discussed [1]. The mosques selected are Bostancı Kuloğlu, Bebek, Kamer Hatun, Yeşilköy Mecidiye and Amine Hatun Mosques (Tab. 1).

Tab. 1: Kemalettin the Architect mosques that were analysed

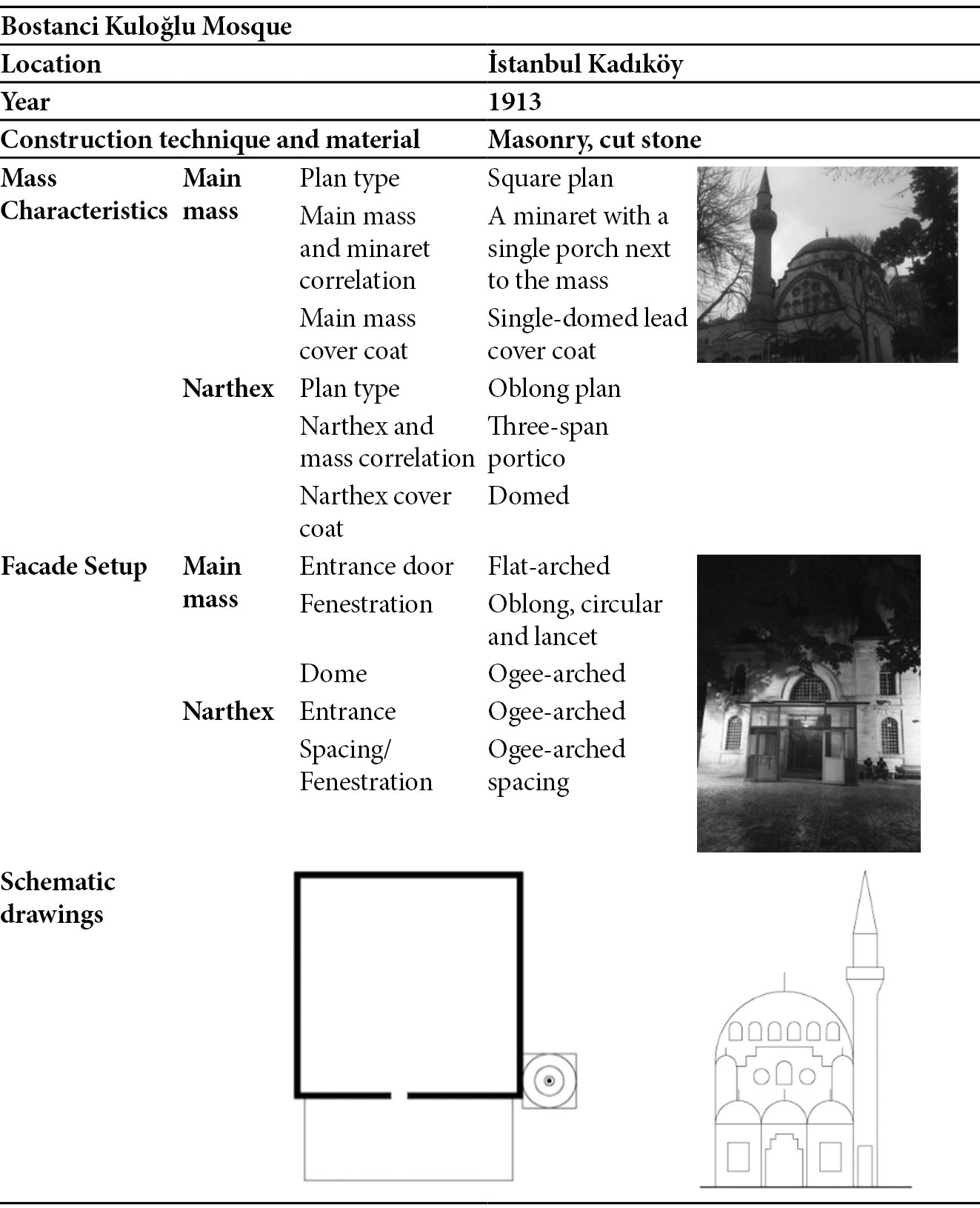

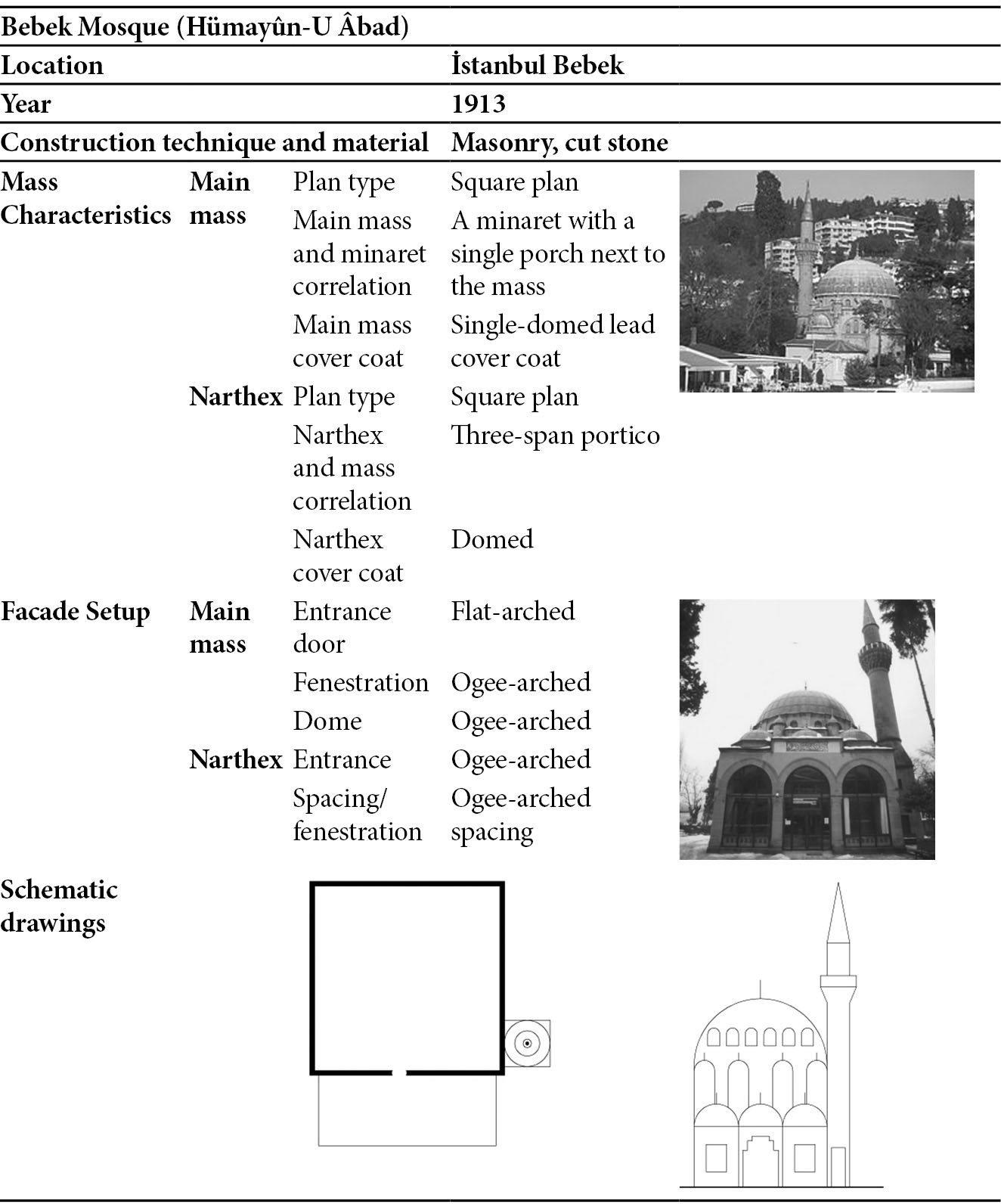

The analyses of selected mosques were not performed at the level of interior space, and were limited with mass characteristics, construction technique and facade setup. The reason for this is the fact that the national architecture movement is a style that mostly focused on facade setup. The title of facade setup includes the main mass and the plan type of narthex sections, their relationship with the main mass, the title of facade setup includes the entrance doors, fenestration and general facade main mass form. The analyses were made on the basis of plan, section, appearance and visuals, schematic drawings of plan and facades were entered into tables.

3.2. Analyses

Kemalettin the architect designed mosques in various cities such as İstanbul, Bandırma, Isparta, Geyve, Konya, Samsun, Aydın and Ankara, but some of them were not constructed [1]. In the context of the study, examples that best reflect and that were built with respect to Kemalettin the architect’s architecture style are analysed (Tabs 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6).

Tab. 2: Bostancı Kuloğlu Mosque mass and facade arrangement analysis

Tab. 3: Bebek Mosque mass and facade arrangement analysis

Tab. 4: Kamer Hatun Mosque mass and facade arrangement analysis

Tab. 5: Yeşilköy Mecidiye Mosque mass and facade arrangement analysis

Tab. 6: Amine Hatun Mosque mass and facade arrangement analysis

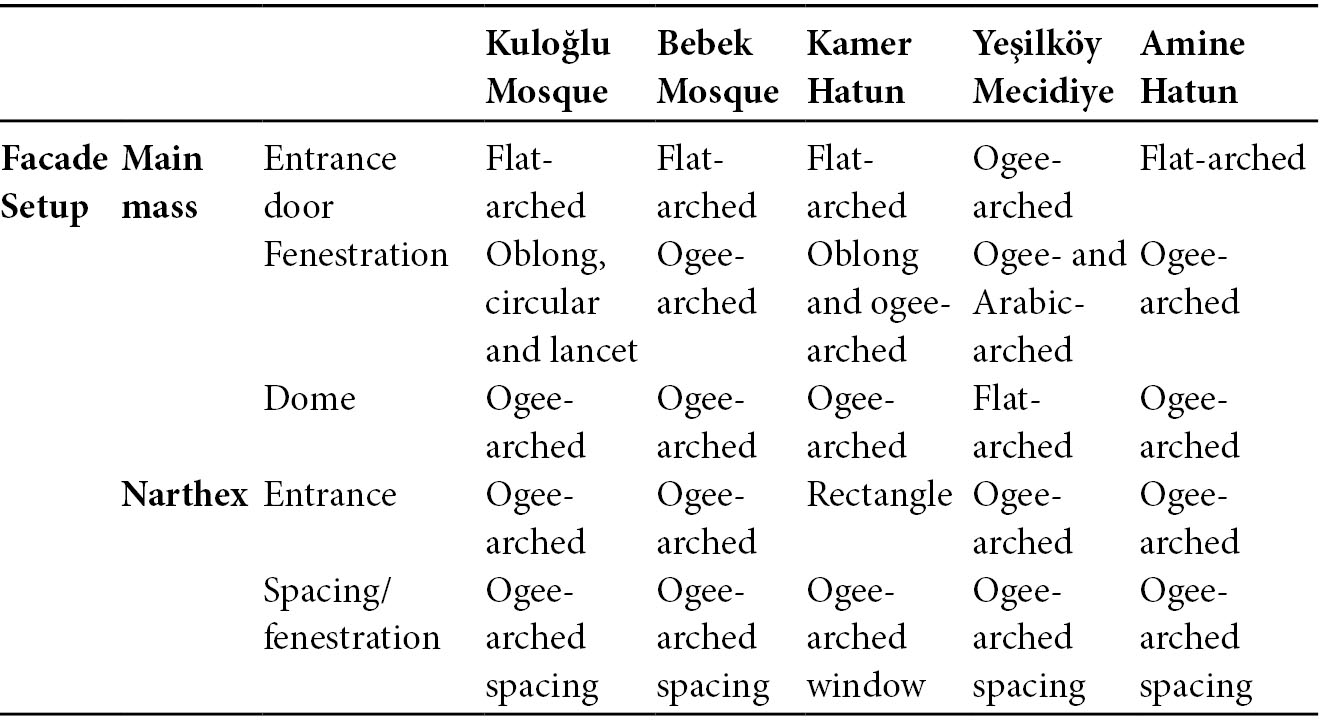

4. Findings

In the context of the study the analyses of the mosques were performed under the titles of mass characteristics and facade setup, and in relation to the literature and visuals. After the analyses were done, schematic drawings were made and ←24 | 25→added to tables. In this context, in the title of mass characteristics, main mass and plan type of narthex sections, their connections to the main mass; in the title of facade setup main mass and entrance doors of narthex sections, fenestration and general facade mass form were included. Findings obtained with regard to these titles are as follows (Tab. 7).

Tab. 7: Mass and facade analyses findings of mosques

Mass Characteristics: In the analyses performed in relation to main mass it is seen that most Kemalettin mosques are square-plan (Kuloğlu, Bebek and Amine Hatun), near-square plan (Kamer Hatun) and inverted T-plan (Yeşilköy Mecidiye). As for the correlation between main mass and minaret, it is seen that the mosques designed are generally single-porch mosques attached to the main mass. Only in Yeşilköy Mecidiye Mosque there is a mosque with a single porch. Cover coating is single-domed lead coating in four mosques (Kuloğlu, Bebek, Yeşilköy Mecidiye and Amine Hatun Mosques). Only in Kamer Hatun Camii lead cover coating is gable-roof. An obvious approach to symmetry can be observed in the plan analyses of the studied mosques.

In the analyses performed on the narthex section it is seen that plan type is square-plan, and that only Bostancı Camii is oblong-plan. If narthex and main mass correlation is taken into consideration, it is seen that they are three-span portico (Kuloğlu, Bebek and Amine Hatun), oblong-plan two-floors and closed (Kamer Hatun, Yeşilköy Mecidiye), in analyses made with respect to narthex and cover coating, it is seen that Kamer Hatun Mosque has a gable-roof cover coating, and all other mosques are domed.

In analyses conducted with respect to facade setup, it is seen that Yeşilköy Mecidiye mosque is ogee-arched, main mass entrance doors are flat-arched. When main mass fenestration is examined it is seen that Bostancı Mosque is oblong, circular and ogee-arched, Bebek Mosque and Amine Hatun Mosque are ogee-arched, Kamer Hatun Mosque is rectangle and ogee-arched, Yeşilköy Mecidiye Mosque is ogee- and Arabic-arched. When main mass and dome fenestrations are examined we can see that Yeşilköy Mecidiye Mosque is flat-arched and all other mosques are ogee-arched.

In analyses done with regard to narthex facade plan it is seen that the entrance is ogee-arched in all mosques, that it is oblong in Kamer Hatun Mosque and that spacing and fenestration consists of ogee-arched spaces.

5. Evaluation

Mosque architecture continued to develop in the 15th and 16th centuries after the single-niche, single-minaret examples in Beylic and Ottoman times, then attained its most mature forms in Sinan’s time, in regression period these structures reflected an eclectic design approach under the influence of the West, and finally, together with the repetition of common examples from the start of their development, they stopped being built within the changing society.

Most of the Empire’s late period mosques are such small-scale structures. Yavuz states that these mosques that were built with the nationalist sentiment ←30 | 31→of those times, with a style inspired by classical Ottoman architecture, do not go beyond being miniature structures striving to reflect the grandeur of the past [1]. Kemalettin the architect mosques that were analysed within the scope of this study confirm the above statement. Even though Kemalettin the Architect was educated abroad, he could not detach his style from the elements of Seljuk and Ottoman architecture. He used arches, tiles and ogee arches. An eclectic approach, in which he reinterpreted arches, is observed.

When we look at the general characteristics of the structures, we see that they are generally single-niche, single-minaret and single-domed. It is seen that the structures examined do not possess any specific typology, especially the facades are similar to each other, but in fact they are facades with distinct designs due to small differences. As for the most prevalent characteristic in plan and facade plan, it is symmetry and symmetry axis is formed by the entrance axis. The entrance is emphasized in all mosques.

National Architecture current and the emphasis of modernism appeared in the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in years where disposal is done understanding of architecture and style. The most important structures that stand out in the society in terms of religious structures in Turkish society are mosques. From this point of view, it is important to preserve the mosque architectural typology of the period today and to transfer it to the next generations.

Details

- Pages

- 788

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631830673

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631830680

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631830697

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783631817926

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17335

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (September)

- Keywords

- urban planning urban design sustainability ecology environment

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2020. 788 pp., 225 fig. b/w, 99 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG