In the Shadow of Djoser’s Pyramid

Research of Polish Archaeologists in Saqqara

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Bibliography

- Chronological table

- Chapter 1. History and archaeology: Saqqara in Egyptian history

- Chapter 2. From Edfu to Saqqara: Polish archaeology in the Nile Valley

- Chapter 3. First steps

- Chapter 4. The vizier’s revenge

- Chapter 5. A testimony to stormy times

- Chapter 6. In the realm of Osiris

- Chapter 7. Cult of the dead

- Chapter 8. The vizier’s posthumous neighbour

- Chapter 9. Behind the scenes of family bliss

- Chapter 10. Renaissance of the necropolis after two thousand years

- Chapter 11. Primum non nocere, or the medicine of artefacts

- Chapter 12. The rest is silence

- Extroduction

- Glossary of deities

- Glossary of archaeological terms

- Glossary of foreign expressions and words

- List of figures

- Illustrations

- Photographs

- Figures

- Authors of the drawings

- Authors of the photographs

- Deities

- Series index

Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche

Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at

http://dnb.d-nb.de.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the

Library of Congress.

The Publication is funded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the

Republic of Poland as a part of the National Programme for the Development of

the Humanities. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the

Ministry cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the

information contained therein.

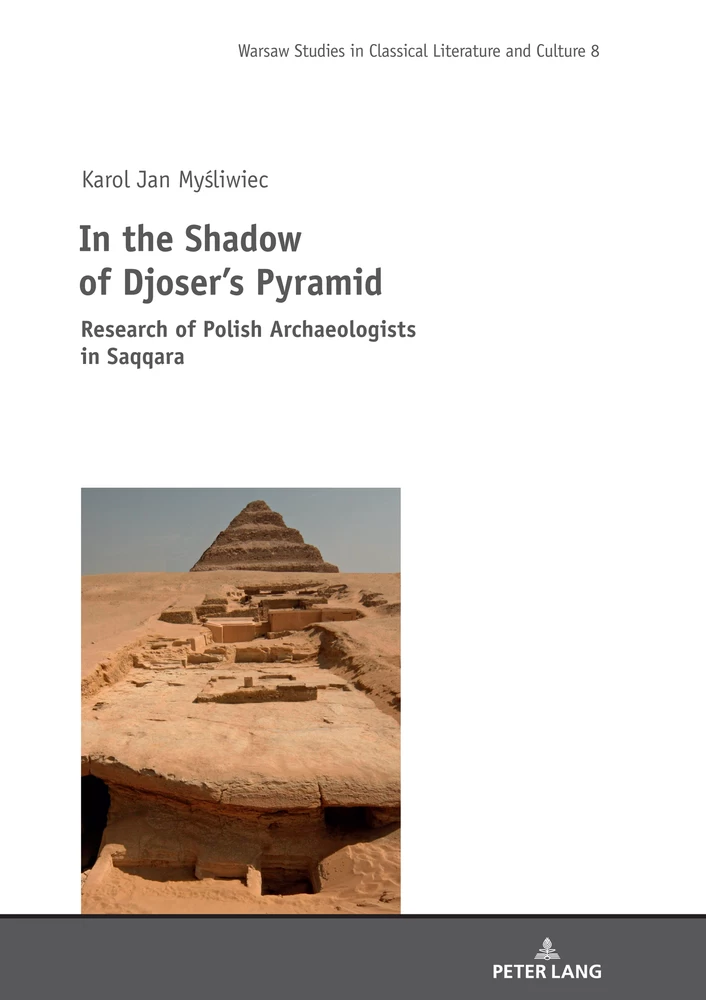

The cover Illustration courtesy for Karol Jan Myśliwiec.

ISSN 2196-9779 ∙ ISBN 978-3-631-81812-1 (Print)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-82059-9 (E-PDF) ∙ E-ISBN 978-3-631-82060-5 (EPUB)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-82061-2 (MOBI) ∙ DOI 10.3726/b16883

Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution

Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this

license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

© Karol Jan Myśliwiec, 2020

Peter Lang – Berlin ∙ Bern ∙ Bruxelles ∙ New York ∙ Oxford ∙ Warszawa ∙ Wien

This publication has been peer reviewed.

About the author

The Author

Karol Jan Myśliwiec, since 1969, has been a member of archaeological missions in Egypt, Syria, Sudan and Cyprus. He was the director of Polish-Egyptian rescue excavations at Tell Atrib (ancient Athribis) (1985–1995) and the head of Polish-Egyptian excavations in Saqqara (1987–2015). He is also the author of 300 publications concerning archaeology, art and religion of Ancient Egypt.

About the book

Karol Jan Myśliwiec

In the Shadow of Djoser’s Pyramid

The book presents the discoveries made by the Polish Archaeological Mission in Saqqara, the central part of the largest ancient Egyptian royal necropolis. The area adjacent to the Pyramid of King Djoser on the monument’s west side, so far neglected by archaeologists, turned out to be an important burial place of the Egyptian nobility from two periods of pharaonic history: the Old Kingdom (the late third millennium BC) and the Ptolemaic period (the late first millennium BC). The earlier, lower cemetery yielded rock-hewn tombs with splendid wall decoration in relief and painting. The book also describes the methods of conservation applied to the discovered artefacts and episodes from the mission’s life.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1. History and archaeology: Saqqara in Egyptian history

Chapter 2. From Edfu to Saqqara: Polish archaeology in the Nile Valley

Chapter 4. The vizier’s revenge

Chapter 5. A testimony to stormy times

Chapter 6. In the realm of Osiris

Chapter 8. The vizier’s posthumous neighbour

Chapter 9. Behind the scenes of family bliss

Chapter 10. Renaissance of the necropolis after two thousand years

Chapter 11. Primum non nocere, or the medicine of artefacts

Chapter 12. The rest is silence

Glossary of archaeological terms

Introduction

“How long will archaeologists continue to dig in Egypt?,” Egyptophiles tend to ask impatiently.

“Till the end of the world,” I answer. And this is no joke. Not because – according to some estimations – the land of the pharaohs is believed to have one third of all the monuments in the world, but rather because the human approach to history is subject to constant change, shifting the very questions that archaeologists ask and are asked.

Many artefacts, which not so long ago seemed to have little historical significance, today are not only an object of intense research but also – as it turns out – have enormous cognitive value. It is no longer merely the lives of rulers that interest us today. For we are willing to better understand our own role in the history of the world, which is why we seek to gain knowledge about how societies and human individuals – as the basic element of this evolution – developed. The first 150 years of the development of Egyptology, from the moment when hieroglyphs were first deciphered and systematic excavations began to be conducted, led archaeological research towards the search for texts, especially those written down on papyrus, and for artworks to enrich museum collections.

The minimal or complete lack of interest in other source materials led to huge, sometimes irreversible losses for the entirety of our knowledge about the ancient world. Modern-day archaeology needs to bridge, at least to some extent, the gaps created by centuries of negligence. One such example could be the huge ancient cemeteries, where the human skeletons were never subjected to anthropological studies, or the very rich ceramic material, from which only vessels preserved fully intact or lavishly decorated were selected for publication. The changes introduced at the turn of the twentieth-first century included such that no archaeological mission conducting excavations in a necropolis can today do research without an anthropologist and a paleozoologist present. A ceramologist has become an essential participant of any excavation, or – increasingly more frequently – a group of ceramologists with various specialisations to correspond to both the richness and diversity of the material.

The conservation of artefacts has become a whole new chapter in this saga. This refers not only to those artefacts that make their way to various museums around the world but also those that remain at the site. For many decades, archaeological missions were least interested in the latter type of artefacts. Rather, they focused on copying texts and documenting the architecture for publication purposes. Some consequences of this were not ←7 | 8→only the disintegration of many, sometimes monumental specimens of stone architecture, but also – and above all – the decay of the polychromy on relief and statue surfaces. Sacral architecture today forms a monochromatic landscape consisting of a grey conglomerate of stone blocks but, in reality, it was the richness of colours that cast the most fascinating allure.

Nowadays, a precondition for conducting an excavation are immediate professional conservation activities aimed at preserving the artefacts in the same state in which they were discovered. This is a difficult task since, before conservation is initiated, the material used by the ancient peoples must be subjected to laboratory tests, which determine the selection of a research methods. Thus, experiments that develop conservation as a science are constantly being conducted on the basis of new archaeological discoveries.

Research methods are also dictated by the particular natural conditions. In these terms, sandy Upper Egypt differs radically from the damp earth of the Nile Delta. Most of all, it is much easier to remove sand than to lead a persistent struggle against underground water. Furthermore, artefacts made from organic materials, e.g. papyrus or wood with a polychrome surface, are not preserved at all in wet soil, or at least not in a very good shape. That is why, for many years, archaeological excavations were focused mainly in Upper Egypt, where the layer of dry sand has long functioned as a natural preservative for the artefacts lying beneath. There were only few excavation missions in the Nile Delta. The pioneers included the 1950s archaeological mission directed by Professor Kazimierz Michałowski in Tell Atrib (the ancient Athribis). The scientific significance of the Delta increased once geophysics was introduced, as it turned out to be the best method of distinguishing the walls built from (dried) mud brick from the damp soil surrounding it. For example, thanks to applying this method, the Austrian excavations in Tell el-Daba brought fantastic results.

However, even at those archaeological sites which were the subject of many archaeological expeditions over the course of more than one hundred years, there are huge ‘blank spots’ that appeared, among other things, as a result of the false conviction about the ‘barrenness’ of certain areas. These would include a large part of the necropolis of the ancient city of Memphis, located at the head of the Delta, on the western side of the Nile. This land of royal pyramids and mastabas (or the tombs of the noblemen) is today one of the two largest concentrations of excavations in Egypt. The second is the Theban district with its centre on both sides of the Nile in Luxor, a few hundred kilometres south of Memphis. In the middle of the Memphite necropolis, one can find Saqqara, symbolised by the ‘step pyramid,’ i.e. the oldest Egyptian pyramid, erected by the legendary architect Imhotep, divinised for centuries. Even though excavations took place near this pyramid in the middle of the nineteenth century, considered to be the very beginnings ←8 | 9→of science-based archaeology, no one continued the research on the western side of the pyramid, in the spot located south of the famous Serapeum, the underground galleries containing the burials of the holy Apis bulls.

It is precisely in this area where the author of this book directed the Polish and then Polish-Egyptian excavation missions. I was a student of Professor Kazimierz Michałowski, who initiated the “Polish school of Mediterranean archaeology” focused on Egypt in 1937–1939, when he directed the French-Polish excavations in Edfu (Upper Egypt). The experiences gathered by this school, in which the conservation of artefacts played an especially important role, include work done not only in such ancient metropoles as Alexandria, Thebes (Egypt), Faras and Dongola (Sudan), Palmyra (Syria) or Nea Paphos (Cyprus) but also cooperation with international excavation missions in the Nile Valley, such as the English mission in Qasr Ibrim, the German-Swiss mission in Elephantine or the German mission in the Theban necropolis (the Seti I Temple).

This book presents the results of the first twenty years of work done by Polish archaeologists in Saqqara.

Bibliography

Full bibliography on the topic from the moment when Polish research was initiated in Saqqara until 2012 can be found in the first five volumes of the series “Saqqara. Polish-Egyptian Archaeological Mission,” which is a source publication for the discoveries made there by the Polish archaeological mission:

Saqqara I: K. Myśliwiec et al., The Tomb of Merefnebef, Parts 1–2, Warsaw 2004.

Saqqara II: T. Rzeuska, Pottery of the Late Old Kingdom. Funerary Pottery and Burial Customs, Warsaw 2006.

Saqqara III: K. Myśliwiec (ed.), The Upper Necropolis.

Part 1: M. Radomska et al., The Catalogue with Drawings, Warsaw 2008.

Part 2: M. Kaczmarek et al., Studies and Photographic Documentation, Warsaw 2008.

Saqqara IV: K. Myśliwiec, K.O. Kuraszkiewicz, The Funerary Complex of Nyankhnefertem, Warsaw 2010.

Saqqara V: K. Myśliwiec (ed.), Old Kingdom Structures between the Step Pyramid Complex and the Dry Moat.

Part 1: K. O. Kuraszkiewicz, Architecture and Development of the Necropolis, Warsaw 2013.

Part 2: F. Welc et al., Geology, Anthropology, Finds, Conservation, Warsaw 2013.

Later publications (for the period 2013–2020) include the following positions:

Godziejewski Z., Dąbrowska U., “Appendix: Conservation work in Saqqara (2012 and 2014),” Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 24/1 (2015), pp. 224–229.

Kowalska A., K.O. Kuraszkiewicz, “The End of a World Caused by Water. The Case of Old Kingdom Egypt,” in: J. Popielska-Grzybowska, J. Iwaszczuk (eds.), Studies on Disasters, Catastrophes and the Ends of the World in Sources (“Acta Archaeologica Pultuskiensia” 4), Pułtusk 2013, pp. 173–176.

Kozieradzka-Ogunmakin I., “Accessory Staff or Walking Aid? An Attempt to Unravel the Artefact’s Function by Investigating the Owner’s Skeletal Remains,” Études et Travaux, 26 (2013), pp. 381–393.

Kozieradzka-Ogunmakin I., “Patterns and Management of Fractures of Long Bones: a Study of the Ancient Population of Saqqara, Egypt,” ←11 | 12→in: A.R. David (ed.), Ancient Medical and Healing Systems: Their Legacy to Western Medicine, John Rylands University of Manchester Bulletin, 89 (2013), pp. 133–156.

Kozieradzka-Ogunmakin I., “Face-to-face with the dead: uncovering the past through the studies of human remains,” Ancient Egypt, 13 (2013), pp. 26–31.

Kozieradzka-Ogunmakin I., “A Case of Metastatic Carcinoma in an Old Kingdom-Period Skeleton from Saqqara,” in: S. Ikram, J. Kaiser, R. Walker (eds.), Egyptian Bioarchaeology: Humans, Animals and the Environment, Leiden 2014, pp. 65–73.

Kuraszkiewicz K. O., “Orientation of Old Kingdom Tombs in Saqqara,” Études et Travaux, 26 (2013), pp. 395–402.

Kuraszkiewicz K. O., “The Tomb of Ikhi/Mery in Saqqara and Royal Expeditions during the Sixth Dynasty,” Études et Travaux, 27 (2014), pp. 201–216.

Kuraszkiewicz K. O., “Marks on the Faience Tiles in the ‘Blue Chambers’ of the Netjerykhet’s Funerary Complex,” in: J. Budka. F. Kammerzell, S. Rzepka (eds.), Non-Textual Marking Systems in Ancient Egypt (and Elsewhere), Lingua Aegyptia. Studia monographica, 16, Hamburg 2015, pp. 41–48.

Kuraszkiewicz K.O., “Generał Ichi – egipski podróżnik z epoki budowniczych piramid,” Afryka, 43 (2016), pp. 155–171.

Kuraszkiewicz K. O., “Architectural Innovations Influenced by Climatic Phenomena (4.2. KA Event) in the Late Old Kingdom (Saqqara, Egypt),” Studia Quaternaria, 31/1 (2016), pp. 27–34.

Kuraszkiewicz K. O., “Saqqara 2012 and 2015: Inscriptions,” Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 25 (2017), pp. 255–263.

Myśliwiec K., “Archaeology Meeting Geophysics on Polish Excavations in Egypt,” Studia Quaternaria, 30/2 (2013), pp. 45–59.

Myśliwiec K., “Sakkara – kopalnia źródeł do historii Egiptu,” Scripta Biblica et Orientalia, 5 (2013), pp. 5–24.

Myśliwiec K., with appendix by Z. Godziejewski, “Saqqara 2010–2011,” Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 23/1 (2014): Research 2011, pp. 153–162.

Myśliwiec K., “The Dead in the Marshes – Reed Coffins Revisited,” in: M. Jucha, J. Dębowska-Ludwin, P. Kołodziejczyk (eds.), “Aegyptus est imago caeli.” Studies Presented to Krzysztof M. Ciałowicz on his 60th Birthday, Cracow 2014, pp. 105–113.

Myśliwiec K., “Epigraphic Features of the ḥr-face,” in: D. Polz, S. J. Seidlmayer (eds.), Gedenkschrift für Werner Kaiser, Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo, 70/71 (2014/2015), pp. 323–338.

←12 | 13→Myśliwiec K., “Das Grab des Ichi westlich der Djoser-Pyramide,” Sokar. Geschichte & Archäologie Altägyptens, 30 (2015), pp. 46–55.

Myśliwiec K., “Neueste Entdeckungen der polnisch-ägyptischen Mission in Sakkara,” THOTs. Infoheft 15. Oktober 2015 des Collegium Aegyptium e.V. Förderkreis des Instituts für Ӓgyptologie und Koptologie, Universität München (2015), pp. 25–34.

Myśliwiec K., “Saqqara: Seasons 2012 and 2013/2014,” Polish Archaeology in Mediterranean, 24/1 (2015), pp. 215–224.

Myśliwiec K., W cieniu Dżesera, badania polskich archeologów w Sakkarze, Warszawa-Toruń, 2016 [the basis for this translation].

Myśliwiec K., “Hole or Whole? A Cemetery from the Ptolemaic Period in Saqqara (Egypt),” in: T. Derda, J. Hilder, J. Kwapisz (eds.), Fragments, Holes and Wholes. Reconstructing the Ancient World in Theory and Practice, Journal of Juristic Papyrology Supplement, 30, Warsaw, 2017, pp. 363–389.

Myśliwiec K., “A ‘School’ of Kagemni’s master?,” in: P. Jánosi, H. Vymazalovà (eds.), The Art of Describing. The World of Tomb Decoration as Visual Culture of the Old Kingdom. Studies in Honour of Yvonne Harpur, Prague 2018, pp. 261–271.

Details

- Pages

- 478

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631818121

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631820599

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631820605

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631820612

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16883

- Open Access

- CC-BY-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (September)

- Keywords

- Mastaba Old Kingdom Art Conservation Iconography Usurpation Political theology Polychromy

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2020. 478 pp., 200 fig. col., 37 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG