Electric Worlds / Mondes électriques

Creations, Circulations, Tensions, Transitions (19th–21st C.)

Summary

Quel(s) regard(s) les historiens d’aujourd’hui portent-ils sur l’électrification, processus engagé il y a près de cent cinquante ans mais auquel plus d’un milliard d’hommes et de femmes restent encore étrangers ? Le présent volume rend compte de la diversité des mondes sociaux électriques et des manières d’enquêter sur leur histoire. Il actualise les connaissances et témoigne du renouvellement de l’historiographie, dans ses objets et ses approches. Quatre points d’interrogation sur le basculement des sociétés dans l’âge électrique jalonnent le volume : moyennant quelles créations ou combinaisons créatrices ? En vertu de quelles circulations et appropriations ? Selon quelles tensions et alliances ? Et produisant quelles transitions et accumulations ?

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents / Table des matières

- Part 1. Creations

- Introduction

- Bright Lights, Brilliant Wits. Caricature and Electric Light in Later Nineteenth-Century Paris

- From Gas to Electric. Georges Seurat, Brassaï and the City of Light

- Electricity at Court. Technology in Representation of Imperial Power

- Architecture in a New Light. Architects and Illuminating Engineers in the Early Twentieth Century United States

- De la circulation à l’appropriation. La patrimonialisation du paysage de néon aux États-Unis

- Part 2. Circulations

- The Branches of Large Electricity Companies in Portugal. From Trade to the Transfer and Adaptation of Technology (Twentieth Century)

- La réglementation internationale – apport de la Tchécoslovaquie à la normalisation électrotechnique en Europe. La coopération de Vladimír List et Ernest Mercier et son importance pour l’introduction du système MIR dans les années 1960 dans les pays du Conseil d’assistance économique mutuelle

- La part des capitaux français dans les sociétés électrotechniques tchécoslovaques durant l’entre-deux-guerres et au début de la guerre froide

- Electrical Colonialism. Techno-politics and British Engineering Expertise in the Making of the Electricity Supply Industry in Cyprus

- Le frère cadet. France’s Contributions to Spanish Nuclear Development, c. 1960s-1980s

- “Spain – Eximbank’s Billion Dollar Client”. The Role of the US Financing the Spanish Nuclear Program

- Part 3. Tensions

- Bias in Electric Power Systems. A Technological Fine Point at the Intersection of Commodity and Service

- Origine et perspectives de l’électrification rurale au Cameroun

- The Akosombo Dam and the Quest for Rural Electrification in Ghana

- Le développement des technologies de l’information et de la communication en Côte d’Ivoire face aux contraintes d’énergie électrique

- Faire dialoguer scientifiques et politiques sur l’énergie nucléaire en France dans les années 1970. Deux initiatives autour du projet Superphénix

- Réacteurs nucléaires mobiles en régions polaires. Le cas controversé de « PM-3A » en Antarctique

- Public Dams, Private Power. Electric Energy and Political Economy in the Post-Second World War US South

- Le barrage des Trois-Gorges. Des déplacements de populations sous contrôle

- Part 4. Transitions

- “Lord, We Don’t Want to Hurt People”. The Decline and Fall of the American Electric Utility Industry in the 1970s

- Designing the Energy Future. Two Narratives on Energy Planning in Denmark, 1973-1990

- Les monuments de la transition énergétique

- Preparing a Solar Take-Off. Solar Energy Demonstration and Exhibitions in Japan, 1945–1993

- Adapting to a Bearish Nuclear Market. The Transition of Framatome in the 1980s

- Is Small Really Beautiful? Operating Early Brazilian Power Plants

- Les quatre phases de l’histoire de l’électricité en Inde, de 1890 à nos jours

- Contributeurs

Pourquoi donc mettre au pluriel le monde électrique dans lequel nous vivons ? Serait-ce une coquetterie académique ? Certainement pas. La pluralité des voies de pénétration et des modes d’utilisation de l’énergie électrique à travers le temps et à travers l’espace impose la prise en compte des effets de temporalités et de localités, en somme des contextes – politiques, culturels, économiques, sociaux – par tout analyste de ce phénomène puissant qu’est l’électrification de la planète. Si l’électricité est portée par la globalisation et en est devenue un ressort, elle n’est pas synonyme d’uniformité. La simple question de l’accès reflète immédiatement cette diversité des situations. La précarité énergétique dans les pays industrialisés et émergents, les coupures et l’absence pure et simple d’accès dans les pays les moins avancés, creusent les écarts plus qu’ils ne les gomment, tant l’énergie électrique dans sa production et sa consommation se révèle structurante pour le quotidien des individus et des sociétés.

« La Fée électricité ne visite pas tous les lieux équitablement », écrivait récemment l’ancien président de la République du Sénégal, Abdou Diouf.1 Ce sont aujourd’hui un milliard de personnes qui vivent sans électricité, dont la majeure partie en Afrique subsaharienne, en particulier dans les zones périphériques et rurales. Des programmes importants d’électrification de l’Afrique coalisent des acteurs très divers, qui placent leurs espoirs dans la fée pour réaliser le conte du développement. Mais en dépit des progrès techniques et des investissements, la résistible électrification de l’Afrique interroge. « Ce qui fait donc défaut, dans tous ces domaines, poursuivait Diouf, ce ne sont ni les financements ni les moyens techniques : ce sont d’une part les cadres institutionnels et économiques adaptés à la variété des situations sociales et culturelles des zones rurales, d’autre part les agents convenablement formés. »2 Où l’on en revient à la nécessité, opérationnelle même et non seulement intellectuelle, du pluriel. Et de conclure : « l’électricité est au coeur des défis africains. Mais, une fois encore, c’est l’homme qui est au coeur des défis de l’électricité. »3 ← 13 | 14 →

Les historiens de l’électricité ont depuis longtemps mis en avant la dimension globale de l’histoire de cette énergie, dès lors notamment qu’ils en ont étudié les vecteurs de diffusion, c’est-à-dire en premier lieu les entreprises de construction et d’exploitation des centrales et réseaux électriques.4 L’Association pour l’histoire de l’électricité en France, dont le Comité d’histoire de l’électricité et de l’énergie a depuis repris et élargi les missions, organisa dès 1986 un colloque dont l’horizon était mondial.5 Hormis une communication sur le Japon, la vision proposée était toutefois centrée sur l’Europe (plutôt de l’Ouest) et l’Amérique du Nord. Quatre ans plus tard, un nouveau colloque approfondissait ces problématiques et s’ouvrait à de nouvelles aires géographiques, en particulier l’Amérique latine.6 S’il abordait aussi les multinationales et les phénomènes de coopération internationale, c’était encore à la marge. Plus nombreuses étaient les contributions où les cadres nationaux ou locaux étaient considérés a priori, sans être interrogés, donnant l’impression au total d’une juxtaposition de cas, séparés les uns des autres, au mieux à comparer. Lorsque nous avons décidé d’organiser en décembre 2014 à Paris un colloque renouant avec cette large perspective mondiale7, notre ambition était de privilégier les études tenant ensemble les effets de circulations et de localités, à travers des approches transnationales, connectées, globales voire impériales qui avaient depuis deux décennies renouvelé l’historiographie de manière générale.

Au bout du compte, les textes issus de ce colloque et réunis dans ce volume ne relèvent pas tous étroitement de ces différentes approches, car celles-ci ne sont pas, loin s’en faut, les seules pratiquées par les historiens qui travaillent sur l’électricité à travers le monde. Aussi présentons-nous ici comme une photographie de la recherche au milieu des années 2010 qui, autour d’un objet commun, révèle la variété des méthodes et des approches engagées. Cette photographie est-elle pour autant représentative ? La question n’est pas de savoir si nous traitons de tout, ce qui n’est évidemment pas possible, mais si nous reflétons les principales directions de la recherche. En ce sens, nous pensons pouvoir répondre par l’affirmative, même si, pour ← 14 | 15 → s’en tenir aux aires géographiques, le volume ne fait peut-être pas justice à l’ensemble des travaux qui peuvent avoir lieu sur l’espace asiatique. Inversement, le volume semble faire la part belle à l’Afrique, du fait sans doute de relations mieux établies avec les communautés académiques des pays concernés, et d’un tropisme francophone. Mais de ce point de vue nous pourrions dire que nous reflétons aussi un printemps historiographique africain, qui accompagne manifestement les efforts d’électrification contemporains présentés plus haut.

Le sommaire de l’ouvrage a été composé en suivant quatre points d’interrogation. Depuis bientôt cent cinquante ans, moyennant quelles créations et destructions les sociétés humaines ont-elles construit ces mondes électriques, ont-elles basculé dans un âge, on pourrait l’oublier à l’heure où le numérique est sur toutes les lèvres, où l’électricité est devenue un fluide absolument essentiel ou désiré, sans lequel le numérique n’existerait pas, et que l’existence de ce numérique rend peut-être encore plus crucial que jamais ? En vertu de quelles circulations et appropriations ? De quelles tensions et alliances ? Et de quelles transitions et accumulations ?

Dans la première partie, la question classique de la création et des dynamiques d’innovation qui caractérisent les systèmes et les cultures électriques, laisse la place à des contributions montrant combien l’électricité a concouru et concourt à la création d’un univers architectural, urbain, artistique nouveau. Car la lumière électrique ne fait pas qu’éclairer : elle permet de lire et de penser différemment la ville.

Les circulations des hommes, des savoirs, des techniques électriques à travers les espaces politiques sont intenses depuis les débuts de l’électricité industrielle, prenant la forme de communications savantes, de visites, de comparaisons. La deuxième partie examine les vecteurs, les plateformes et les effets de ces échanges.

La troisième partie rend compte du caractère à la fois technique et politique de l’électricité, en traitant des tensions que celle-ci génère immanquablement. Spatialement dévorantes, les infrastructures électriques posent sans discontinuer la question du rôle des citoyens et des consommateurs dans le processus de décision.

Enfin, consacrée aux transitions, la quatrième partie inscrit les dynamiques de l’électricité dans une histoire plus large des énergies. Aborder les transitions à travers la focale de l’électricité montre qu’il est nécessaire de les aborder moins comme des substitutions que comme des superpositions ou additions. Quoi qu’il en soit, il n’est plus concevable de jauger comme jadis le niveau de prospérité d’un pays à son standard de consommation d’électricité. Les sociétés les plus consommatrices ne sont pas seulement devenues post-industrielles mais « énergie-mature », ce qui implique des défis nouveaux pour le vecteur électrique. ← 15 | 16 →

1 Abdou Diouf, « Préface » à Christine Heuraux, La formation au coeur du développement : réussir l’électrification rurale en Afrique (Paris : L’Harmattan, 2011), 9-11, 9.

2 Ibid., 10.

3 Ibid.

4 Albert Broder, « La multinationalisation de l’industrie électrique française, 1880-1931. Causes et pratiques d’une dépendance », Annales ESC 39/5 (1984) : 1020-1043 ; Pierre Lanthier, « Les constructions électriques en France : financement et stratégies de six groupes industriels internationaux de 1880 à 1940 » (Ph.D. Diss., Université Paris 10, 1988) ; William J. Hausman, Peter Hertner, Mira Wilkins, Global Electrification. Multinational Enterprise and International Finance in the History of Light and Power 1878-2007 (New York : Cambridge University Press, 2008).

5 AHEF, Un Siècle d’électricité dans le monde, 1880-1980 (Paris : PUF, 1987).

6 AHEF, Électricité et électrification dans le monde, 1880-1980 (Paris : PUF, 1992).

7 Mondes électriques / Electric Worlds. Créations, circulations, tensions, transitions (19e-21e siècles), Espace Fondation EDF, Paris, les 18 et 19 décembre 2014.

Caricature and Electric Light in Later Nineteenth-Century Paris

Abstract

Paris as la Ville Lumière is indelibly linked to abundant gaslight, which proliferated starting in the 1840s and 1850s, and remained the city’s dominant form of outdoor éclairage throughout the Belle Époque and beyond. The French capital was however one of the first cities in the world to experiment with the newest forms of highly technologized streetlight: electric arc lighting. Between 1878 and 1882, undivided arc lamps (Jablochkoff candles) were put in service experimentally on prominent thoroughfares in some of the city’s more prosperous quartiers, including the environs of the new Opera House. The blazing lights drew interminable commentary. The culture-wide preoccupation with electric light reached fever pitch during the 1881 Exposition Internationale d’Électricité, held in the Palais de l’Industrie, the largest and most diverse display of electric lights in history, including four kinds of incandescent electric light, the eventual world standard.

The inventor of the most influential form of incandescent light, the American Thomas Edison, the so-called genius of Menlo Park, shortly became electric light’s metonym. His seemingly boundless energy and inexhaustible risibility coupled with the dazzling new lights of the era were godsends to the caricaturists and illustrators of Paris. This paper examines aspects of the pictorial response to Edison, the new éclairage, and its social effects by focusing upon the work of three major graphic satirists: Cham (Amédée Charles Henri de Noé, 1818-1879), Draner (Jules Jean Georges Renard, 1833-1926), and Albert Robida (1848-1926).

Keywords: Jablochkoff, gender, caricature, humor, éclairage

*

Introduction: New luminosities and comic art

The newfangled éclairage of the final decades of the nineteenth century altered the visual environment of central districts of the city of Paris, and ignited vivid social scenarios. This state of affairs was an enormous benefit to graphic artists, especially those working in a comical ← 17 | 18 → vein. Inspiration was ubiquitous; there seemed to be new lights blazing in different locations everyday sewing confusion and amusement. Who could keep up? What caricaturist could resist? The spectacular one-off exposition showcasing electric lights, l’Exposition Internationale d’Electricité, held in the Palais de l’Industrie in 1881, and the novel illuminations in the French capital, les bougies Jablochkoff, installed in prestigious parts of the city between 1878 and 1882, were significant sources of humorous imagery. The simultaneous consolidation of the polyvalent celebrity of electric light’s metonym, Thomas A. Edison, was also providential: the confusing effects of the new illumination and the risibility of the legends attaching to Edison sparked new lines of wit. Humor provoked by various visually dazzling environments, on one hand, and the Genius of Menlo Park, on the other, revivified two of the thematic mainstays of mid-century periodical-based Parisian caricature of earlier decades: the sizable opportunities for sexual mischief in Paris, and the cluelessness of Americans.

The concurrence of the era of nonstop innovation in electric light and the 1880 founding (as well as a revival) of La Caricature by Albert Robida (1848-1926) were a boon for Parisian visual culture. Robida’s journal is our point of entry into the thematics of electricity and electric light in the comic visual arts. The publication’s razor-sharp visuals shine a bright light upon some of the signature beliefs and preoccupations in circulation on the Parisian sociocultural scene in and around 1880 – at least in the eyes of the subscribers to Robida’s 8-page weekly. The corpus of caricatural responses to the new lighting scenarios in La Caricature and elsewhere mined in this essay tests some of the leading theories of the distinguishing achievements of the modern idiom of caricature. On one end of the theory axis, caricature is defined as an inherently democratic and potentially subversive genre; and thus a potent tool of counter-discourse and ridicule. At the opposite end, caricature is construed as an irretrievably conservative mode, whose purpose is taxonomization and the recycling of types. This interpretation navigates between the far poles of caricature theory, but gravitates towards the latter cluster of thought defining it as a mode that repeats and reinforces the traits of pre-established types.

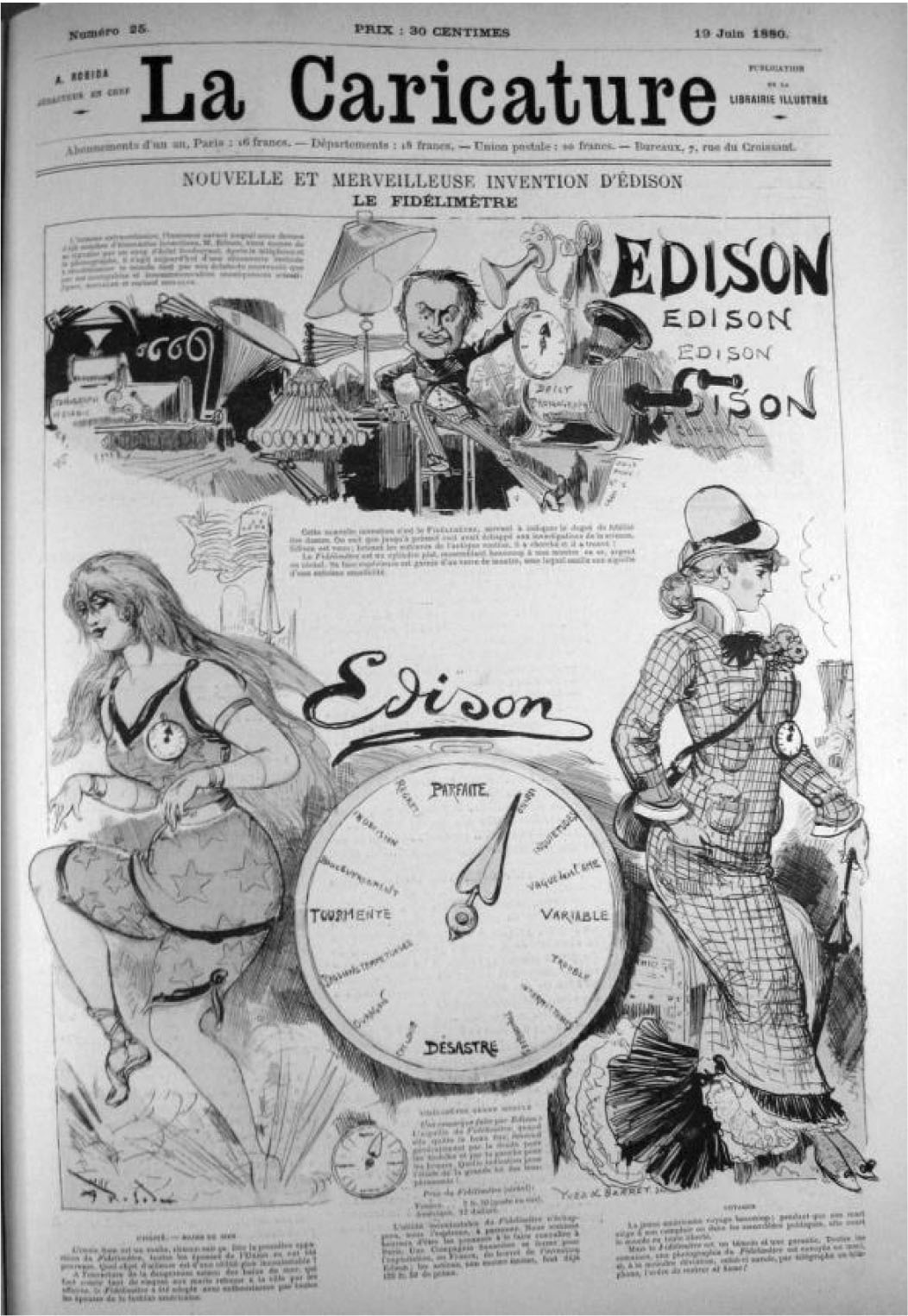

Hilarious and ludicrous situations fostered by new lights as well as other electric contraptions may have motivated Robida’s publishing venture. The journal’s specialization under his direction was la caricature des moeurs, an intentionally less political program than that followed by the 1830s publication of the same name edited by Philipon. The front page of the June 19, 1880 issue, an amalgamation of picture and text by Robida himself, showcased the journal’s prowess in the realm of social caricature. “Nouvelle et Merveilleuse Invention d’Edison” (“New ← 18 | 19 → and Marvelous Invention by Edison”) (figure 1), a tour de force of the humorous imagination rooted in actuality, starred the angular and wildly charged-up Thomas Edison in his laboratory. June 1880 was well into the flowering of the American inventor’s transatlantic reputation as the Wizard of Menlo Park, a term used famously by Villiers de l’Isle Adam in his novel, L’Ève future, begun in 1878. The successful test of the Edison bulb in New Jersey in late 1879 secured Edison’s reputation as electric light’s flashiest prodigy, dispelling most of the doubts that had governed the thinking about him in the French électricien crowd.

Figure 1. Albert Robida, “Nouvelle et Merveilleuse Invention d’Édison: Le Fidélimètre,” La Caricature, 19 juin 1880

Courtesy of Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. ← 19 | 20 →

In Robida’s front-page scenario, a fiercely determined Edison has invented a preternaturally clever contraption that harnessed the omnipotent force par excellence, electricity, in order to satisfy the perpetual husbandly need to track and control the romantic meanderings of unsupervised wives. The device, brilliantly named, was the Fidélimètre designed “à indiquer le degré de fidélité des dames” (“to indicate the degree of faithfulness of women”) by tracing the ups and downs of perpetually erratic young women, the temperamental twins, albeit married, of Verdi’s “la donna e mobile” (Rigoletto).1 A woman would sport the gadget as if it were a flattened pocket watch, pinned like a brooch or dangling from a fob. The dial registers her actions and intentions between two extremes, from PARFAITE (perfect) to DÉSASTRE (disaster).

The women tricksters modeling the device are both Americans, feral modern women par excellence. It should not come as a surprise that a joke defining Edison as the nec plus ultra of technological wizardry derides American mores at the same time. As the literary scholar Mike Goode maintains, “In many cases, the primary purpose of an image [in caricature] seems to have been to specify or recycle a particular character type or set of types.”2 Admiration for Edison’s gadgets had moreover to be undercut by the deadly serious and frequently fierce transatlantic economic and cultural struggle over the ownership of electricity. The gag is leavened by another trope of Parisian boulevard humor: American women are cheeky and insolent compared to les Françaises.

At right is the urbanite with a Chicago sticker on her steamer trunk; a train belching steam is close by. Under the heading, VOYAGES, she is dressed sharply to roam freely.

The young American travels a lot; while her husband sits at his counter or in political assemblies, she runs around the world in complete freedom. But the Fidélimètre is a witness and a guarantee. Every week, a photograph of the Fidélimètre is sent to the husband, and, if there is the least deviation, he sends, by telegraph or telephone, the order to return home (“rentrer at home”).3

The other young American, bounding into the surf in bathing costume with long hair loosely streaming, demonstrates the benefits of the device at ← 20 | 21 → the seashore under the heading, UTILITÉ – BAINS DE MER (Usefulness – Seaside Resorts).

Uncle Sam is cunning, everyone knows that. As soon as the Fidélimètre was available, all the spouses in the States were provided with them. Besides what object has a more incontestable usefulness? At the opening of the dangerous season at the seashores, which run so many risks for the husbands stuck in the city by their business affairs, the Fidélimètre was adopted with enthusiasm by all the spouses in the American fashion.4

The social and technological modernity of the contraption was thus all-inclusive. Nothing less could be expected from the capacious mind of Robida whose ability to imagine the future ingeniously was unparalleled.5 In the “Fidelity Meter,” the American inventor’s outsized talent is seen through the lens of Robida’s singular comic dexterity; Edison’s mechanical brainchild commingles the resources of an electric sensor, photography, telegraphy and the telephone. Robida nonetheless trivializes Edison’s futuristic inter-medial contraption. Indeed a clear sign of Robida’s comic dexterity is his ability to lionize and belittle Edison’s resourcefulness simultaneously, all the while keeping the laughs flowing. All that know-how, the jest starring two American females assures us, is marshaled merely to perform a housekeeping task: keeping irksome Américaines in line. Its hilarity and originality drink deeply from the wellspring of Parisian stereotypes – about American men (credulous cuckolds) and women (morally lax), and the upstart inventor himself (a wily genius solving a trivial problem). Female viewers who may admire the agency of the Americans in this program on the brink of outfoxing authoritarian spouses are not allowed the pleasure of positive identification and recognition because the mobile women are imagined to be under the control of an electric behavior tracker. ← 21 | 22 →

Laughing at lights in the street

The piercing glare of the arc lamp street lights (Jablochkoff candles) put in place in high profile sites in Paris between 1877 and 1879 (and continued at some locations through 1880, 1881, and early spring of 1882) was a rich source of inspiration for both Draner (Jules Jean Georges Renard; 1833-1926) and the indefatigable Cham (Amédée Charles Henri de Noé; b. 1818) during the last year of his life – he died on September 6, 1879. Cham exploited the comic potential of the blinding glare in many lithographs, most of them set in the spaces adjoining Charles Garnier’s new Opéra, opened in 1875. The Avenue de l’Opéra was inaugurated on September 19, 1877, and the very same evening, the façade of Garnier’s Opéra was illuminated by Jablochkoff carbon arc lights.6 Garnier was a passionate advocate of electric light, and was committed to its possibilities for lighting the interior of his lavish building.7 Indeed, on October 18, 1881 (during the run of the Electricity Exposition), according to Christopher Mead, “the entire public half of the Opéra, exterior as well as interior, was illuminated by systems invented by Jablochkoff, Edison, Swan, and others.”8 The avenue itself was lined with Jablochkoff candles in 1878.9

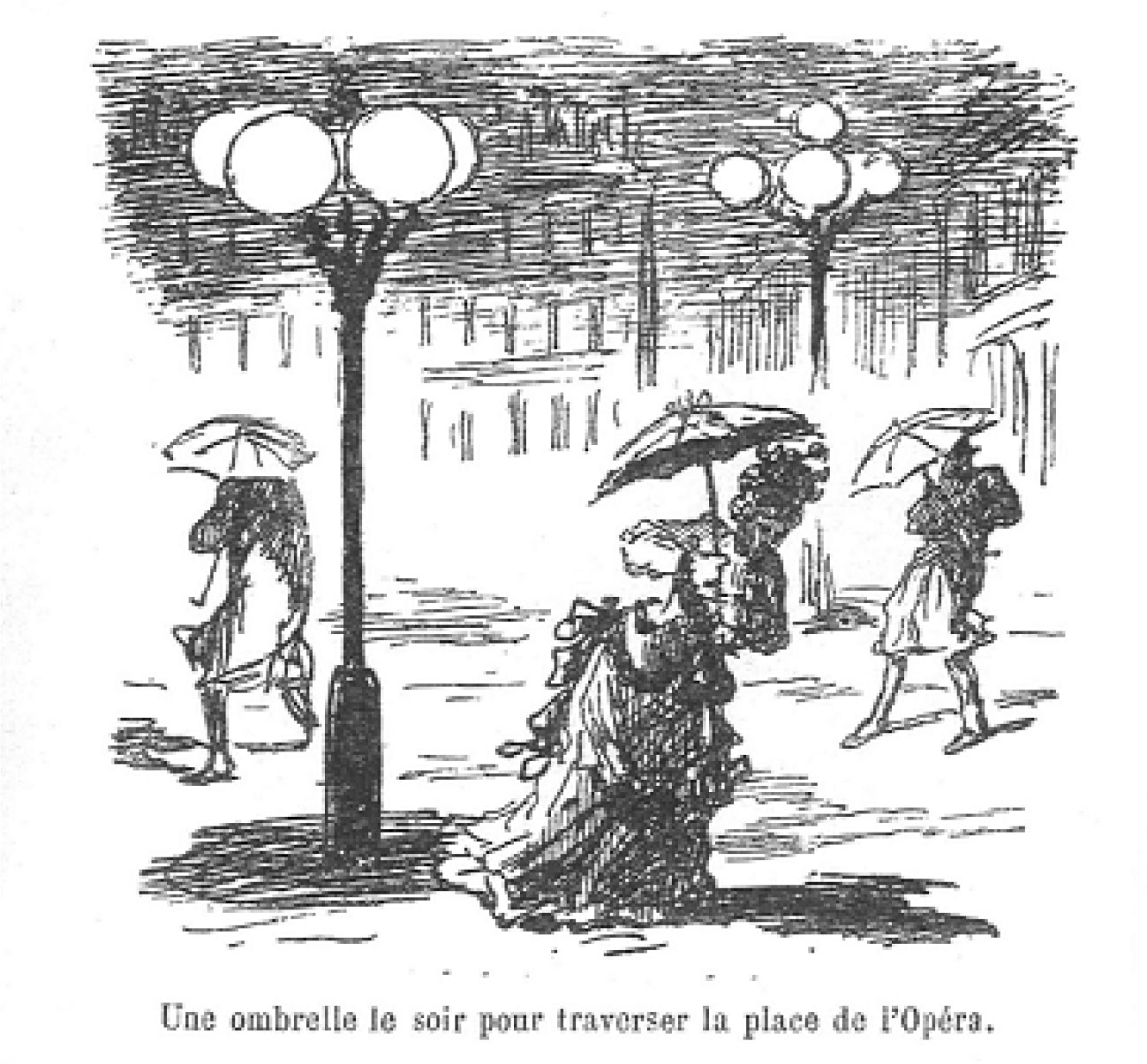

Cham’s attraction to the Opera building and its surroundings can be explained in two ways: the location was a high profile site of electric arc lighting, and le comte de Noé was a close personal friend of Charles Garnier. He mined the humor of streetlamp-caused eye trouble in the Place de l’Opéra repeatedly. “Une ombrelle le soir pour traverser la place de l’Opéra” (“An umbrella to cross the Place de l’Opéra in the evening”) (figure 2) enlists the support of the deracinated modern urban eye shield par excellence, the umbrella deployed at night when the weather is dry and the sun is down. Amongst the three struggling nighttime protagonists, the torsion in one man’s stance and the severe tilt of the woman’s body inscribe the intensity of the physical effort ← 22 | 23 → necessary to outfox the penetrating rays. The postures also amusingly emulate the typical postures of bodies beset by heavy rain or strong winds.

Figure 2. Cham, “Une ombrelle le soir pour traverser la place de l’Opéra,” Les Folies Parisiennes par Cham: Quinze Années Comiques 1864-1879, Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1883, 43.

Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

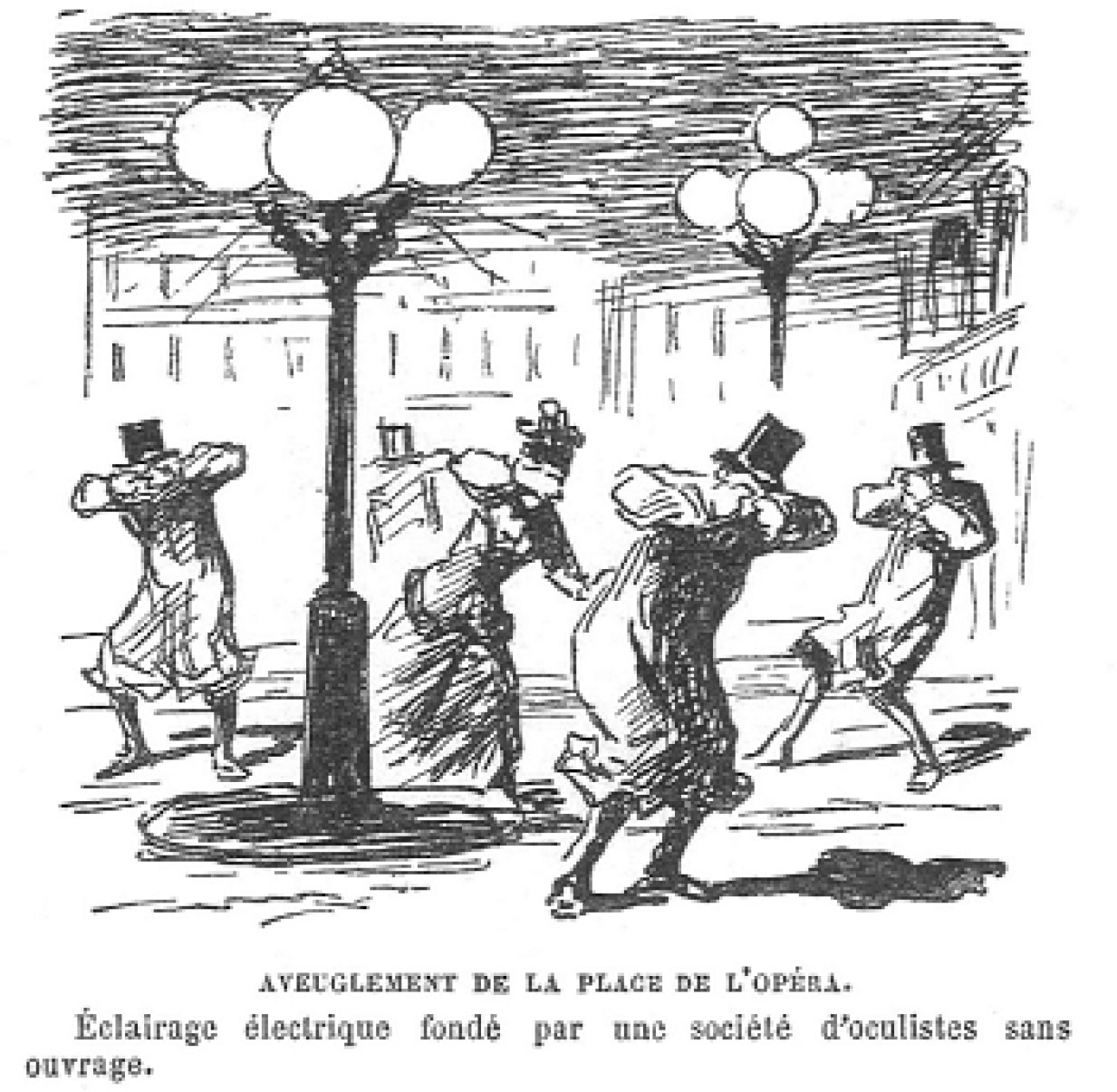

“Aveuglement de la Place de l’Opéra” (“Blindness in the Place de l’Opéra”) (figure 3) references the coterie of professionals often imagined to benefit directly from the emplacement of the new lights, oculists. Here the witty caption aligns the wounding electric light with a deliberate move on the part of an organized league of unemployed eye specialists: “Éclairage électrique fondé par une société d’oculistes sans ouvrage” (“Electric light established by a society of unemployed oculists”). ← 23 | 24 →

Figure 3. Cham, “Aveuglement de la Place de l’Opéra,” Les Folies Parisiennes par Cham: Quinze Années Comiques 1864-1879, Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1883, 43.

Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

The comic drawings by Cham raise questions about audience. In his witty scenarios of light-caused inconvenience, are the bourgeois pedestrians battling the environment the laughers or the laughed at? Is electric light under assault in these drawings, or are its opponents made to appear ridiculous? I would argue that the bourgeois lampooned in Cham’s work are not literally caricatured; not given exaggerated features, so that in the context of Cham’s gentle humor, they are encouraged and expected to laugh at themselves.

Period medical specialists understood the correlation between bright light and eye damage, a standby of both comic art and popular journalism, more complexly. Dr. N. Théodore Klein, Parisian ophthalmologist, posed the key question in 1873: “Must we admit, with all those who have written on this subject, that visual acuity diminishes when the light is too strong?” Then come the answers, at first indicating that exposure to intense light produced ocular damage. “Very intense lighting, like electric ← 24 | 25 → light, produces a painful excitation that few people can even bear.” But it quickly becomes clear that in Klein’s judgment the case against electric light was not the open and shut one delivered by caricature and the anti-electricity crowd. Klein again: “But we have always observed, following the first moment of dazzle, an augmentation of sharpness.”10

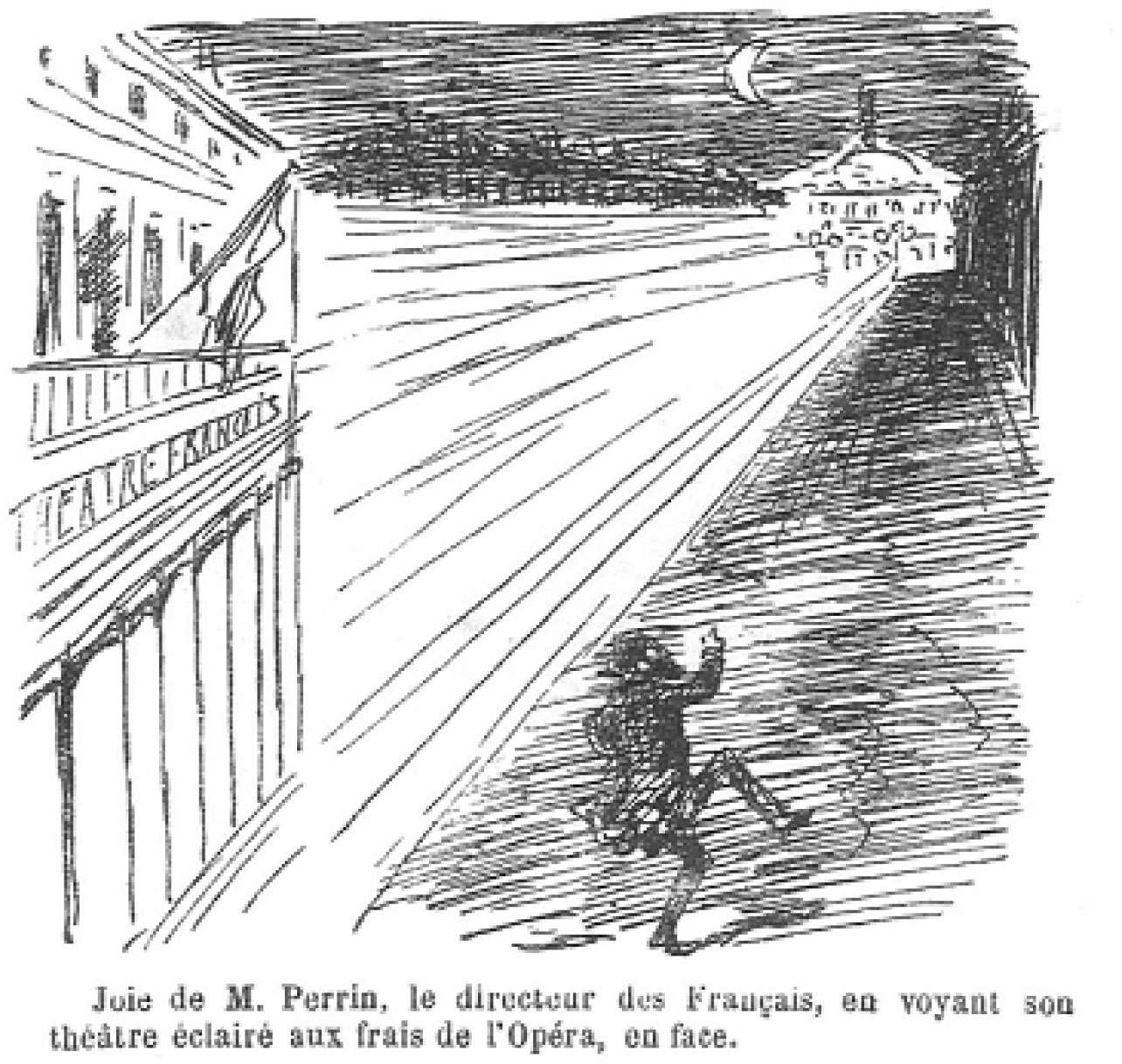

Figure 4. Cham, “Joie de M. Perrin,” Les Folies Parisiennes par Cham: Quinze Années Comiques 1864-1879, Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1883, 261.

Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. ← 25 | 26 →

“Joie de M. Perrin” (figure 4), another 1879 comic drawing by Cham, again engaged the glare, but in a different key. Rather than joking about the somatic price paid by Parisians in the immediate vicinity of prestigious musical culture, this print envisions the Opera district from above occupied by a solitary and singular Parisian, the Director of Le Théâtre Français. Cham jubilantly dissolves the avenue into a blazing river of electric light, a luminous ribbon that shoots down its full length. Like the ramrod straight tale of a comet, it cuts a broad swath across the 1er and 2e arrondissements connecting its two celebrated cultural institutions. The shimmering electric candelabras in the place before the façade of Garnier’s building appear to have generated the luminous stream completely obliterating the avenue in the process; erasing all its fixtures and features. What’s more, as a result, Le Théâtre Français is ablaze for free: “éclairé aux frais de l’Opéra;” lighting courtesy of the Opera. The only competing point of light on this extraordinary Paris evening is the crescent moon shining in the dark sky, electric light’s antagonist and the drawing’s marker and reminder of natural night. M. Perrin, the director of the Théâtre Français, dances for joy just outside the stream of light, exuberantly alone alongside the radiant avenue. His energetic dance combines delight, surprise and chagrin. Cham’s clever concoction enables M. Perrin to appear both discomfited by the miracle of light and intoxicated by it simultaneously. The observer would smile, I would argue, but not laugh. By fancifully dissolving an avenue in light, Cham shows himself to have been one of the rare French artists who reacted to the particularities of the white blaze of Jablochkoff street lights in the realm of aesthetic form.

Caricature in the spotlight at the electric Salon

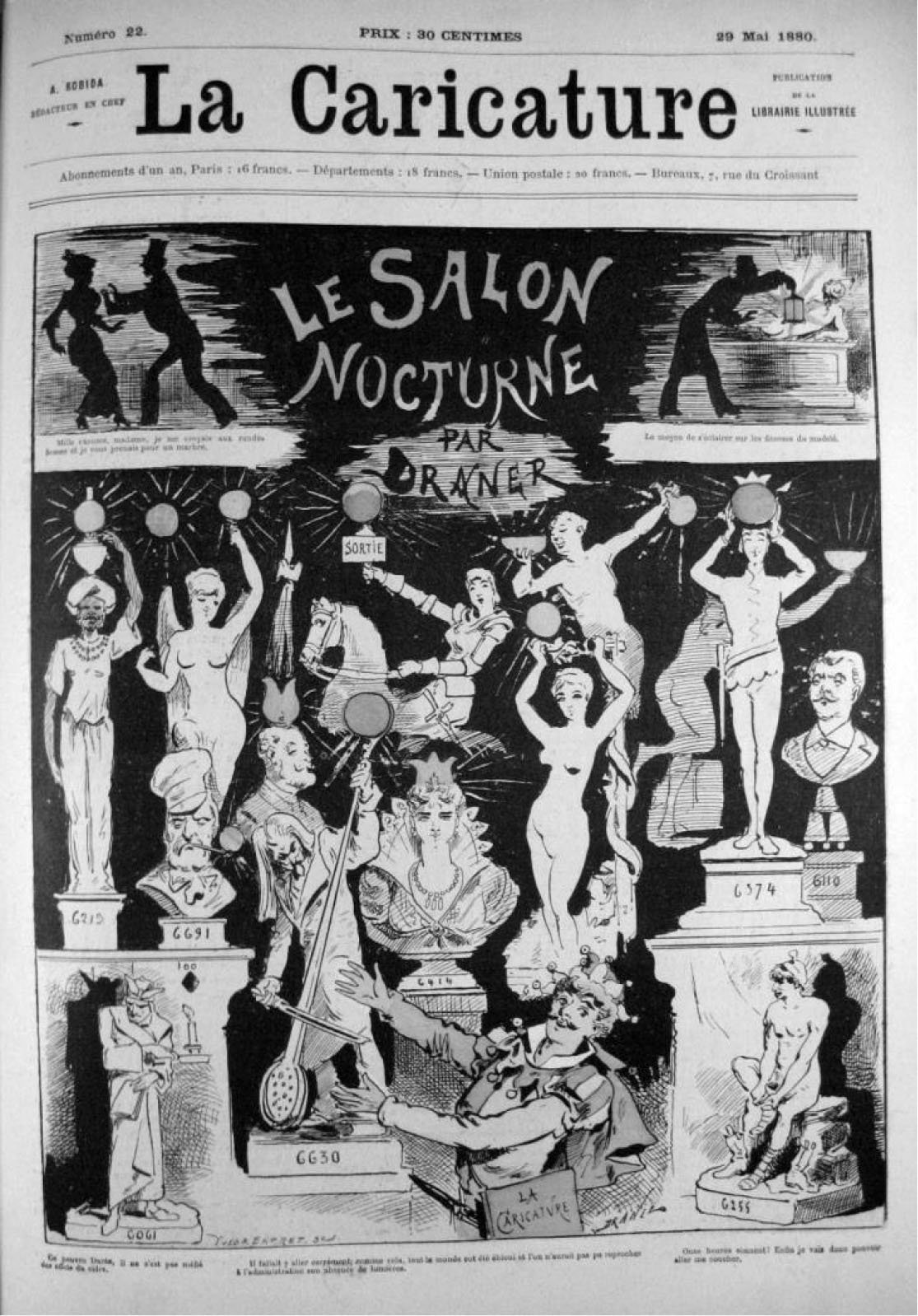

Caricaturists, experts in ridicule, exaggeration and the re-inscription of the already known, were ingenious readers of the effects of the multivalent electric lamp: as nothing but a gimmick that dazzled, and as a cunning contraption that ushered socially and morally fraught scenarios into being imagined to illuminate social and personal “truths” normally concealed by darkness. Robida, the editor of La Caricature, assigned his seasoned colleague, Draner, to the 1880 electric Salon. His full-page multicolor sculpture gallery (figure 5) is an ingenious exegesis of the event. Surely the artists of La Caricature could not have guessed that it would be both the paper’s first foray into an electric Salon (the 29 May issue was only the journal’s twenty-second) and its last. The lighting experiment only lasted two years: it was terminated prior to the 1881 Salon. ← 26 | 27 →

Figure 5. Draner, “Le Salon Nocturne,” La Caricature, 29 mai 1880.

Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Draner’s caricatural nighttime visit is funny, but its hilarity is rooted more in facts than fiction. All but one of the numbered statues that crowd the page are “real” identifiable as sculptures that were on display. That said, aspects of the picture that are absurd are the intentional haphazardness and small size of the ensemble: Draner shows only fourteen of the seven hundred pieces of sculpture that appeared that year, all in the lamp-lit nave on the ground floor. The careful attempt I make in what follows to match up Draner’s white statues and their object numbers to those listed in the Salon Livret is thus both painstaking forensic art history, and a way ← 27 | 28 → of certifying the ludicrousness of Draner’s grouping despite the general fastidiousness of his references.11

The balls of glowing brightly colored red and yellow light stand in for the piercing white globes of arc light. Their fanciful colors may function as exaggerated registrations of the characteristic “scintillations” that distorted color. They are also amusing in their animation of the crowded tiers of white sculpture like buoyant toys bouncing about and floating amongst guests at a merry party shorn loose from their rods, poles and batteries. The coronas of linear rays that emanate from the spheres indicate the high wattage of their radiance. That the spherical globes also appear to function within some of the sculptures’ own narratives or to provide new-fangled attributes is part of Draner’s spirited game rooted in a playful attitude towards the untouchable, buzzing and glaring globes of the real Jablochkoff candles.

Draner’s definition of the light sources in play on the page is elaborate and detailed. There are only four old style (pre-industrial) lights in this nocturnal Salon, and only two of the sculpted bodies cast shadows, choices that enhance the delineation of light source-specific effects. No. 6219 is a completely fanciful, dark turbaned Oriental man who does not correspond to the exhibit displayed under that number; he is the only figure in Draner’s Salon with an old-fashioned light on his head, an oil lamp.12 The Orient is thus cheekily linked to out of date artificial light.13 The Oriental’s lamp glows bright yellow, and the imposing female bust (No. 6414) at center shows also gives off a yellow light; she has a candle flame on her head in the regal shape of a three pronged crown.14 The unnumbered bust of a smug bearded man (behind the wild No. 6630, “le démon de Rakoczy”) also dons a flame on his pate, two-lobed in his case, and the male bust at the far right (No. 6110) is singular in radiating its ← 28 | 29 → own globe-free rays of light, presumably those of genius, suitable for a professor.15 Joan of Arc, the great heroine of France, is reduced to an exit sign. Indeed this kitsch diminution of her stature – she’s nothing but a lamp! – powerfully suggests that arc light devalues sculpture. Draner’s program sides with a widespread opinion: nothing is more anti-art than electric light.

Another sort of character occupies the bottom register. The spindly robed figure casting a dark shadow (No. 6061) at left is Dante holding a candle. His caption classifies him as a tipsy nightwalker. “Poor Dante, he was not on his guard against the effects of cider.”16 At right the helmeted and muscular seated naked man (No. 6255) removing his boots and socks can be identified as Mercury. He sits atop a caption that explains his unshod feet: “11 o’clock sounds! Finally I’ll be able to put myself to bed.”17 Mischievous captioning thus puts both Dante and Mercury, the grandest personages on the entire page with the exception of Joan of Arc, in all too human conditions: intoxication and impatient drowsiness. They retain some modicum of dignity however by being spared the possession of an electric light. All the other figures have become lamps; not merely illuminated but converted into machinic commodities by Jablochkoff candles.

More complex and consequential is the caption below center, positioned as if spoken by the colorful yellow- and red-clad jester, our guide, who carries a portfolio across his body labeled La Caricature, and gestures towards the illumined congregation of art works.18 “There should have been decisive action, that way everyone would have been dazzled (blinded) and nobody could have complained about the administration’s lack of enlightenment.”19 ← 29 | 30 → This statement is a puzzle in many ways, but it unquestionably addresses the administration’s decision to illumine the Salon with electric arc light. It certainly plays on the familiar discursive rhyming and standoff between bedazzlement and enlightenment. Does it mean that the lights should have been left on all night? Or does it reference discussions underway during the month of May about the efficacy and politics of lighting the Salon with electricity? We are faced by another example of caricature’s defining but retroactively vexing contingencies that we are unlikely to be able to sort out conclusively at this remove.

Details

- Pages

- 606

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9782807600287

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9782807600294

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035266054

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9782875743305

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0352-6605-4

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (January)

- Keywords

- Électricité Histoire électrification énergie

- Published

- Bruxelles, Bern, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2016. 603 pp., num. ill. and tables