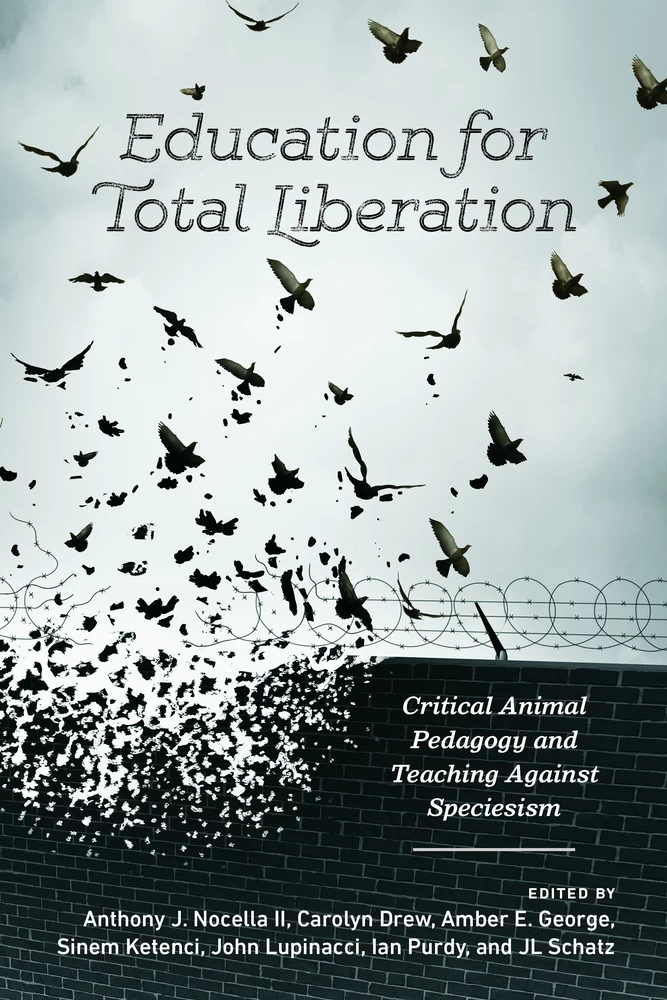

Education for Total Liberation

Critical Animal Pedagogy and Teaching Against Speciesism

Summary

Contributing to this collection are Anne C. Bell, Anita de Melo, Carolyn Drew, Amber E. George, Karin Gunnarsson Dinker, Sinem Ketenci, John Lupinacci, Anthony J. Nocella II, Sean Parson, Helena Pedersen, Ian Purdy, Constance L. Russell, J.L. Schatz, Meneka Repka, William E. Shanahan III, and Richard J, White.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- Praise for Education for Total Liberation

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Examining the Nexus: Critical Animal Studies and Critical Pedagogy (Carolyn Drew / Amber E. George / Sinem Ketenci / John Lupinacci / Anthony J. Nocella II / Ian Purdy / J.L. Schatz)

- Part I: Foundations

- 1. Unmasking the Animal Liberation Front Using Critical Pedagogy: Seeing the ALF for Who They Really Are (Anthony J. Nocella II)

- 2. Beyond Human, Beyond Words: Anthropocentrism, Critical Pedagogy, and the Poststructuralist Turn (Anne C. Bell / Constance L. Russell)

- Part II: Pedagogy

- 3. Critical Animal Pedagogy: Explorations Toward Reflective Practice (Karin Gunnarsson Dinker / Helena Pedersen)

- 4. Our Heroes Need to Wear Ski-Masks: The Animal Man and the Animal Liberationist Hero in Comics (Sean Parson)

- Part III: Educational Industrial Complex

- 5. Teaching to End Human Supremacy↔Learning to Recognize Equity in All Species (John Lupinacci)

- 6. Intersecting Oppressions: The Animal Industrial Complex and the Educational Industrial Complex (Meneka Repka)

- Part IV: Lessons from the Classroom

- 7. “We are one lesson”: Some Reflections on Teaching Critical Animal Geographies Within the University (Richard J. White)

- 8. Teaching the Animal in Foreign Languages: An Ecopedagogical Approach (Anita de Melo)

- Part V: Activism

- 9. Activist Education for Animal Ethics: The Imperative of Intervention in Education on the Non/Human (J.L. Schatz)

- 10. Building Alliances for Nonhuman Animals Using Critical Social Justice Dialogue (Amber E. George)

- Part VI: Decolonizing

- 11. Decolonizing Critical Classrooms, Decentering Animal Pedagogies ( William E. Shanahan III)

- Contributors

- Index

- Series Index

The editors of this book would like to thank everyone involved with Peter Lang Publishing for believing in and supporting this project. We would like to thank everyone involved with the Institute for Critical Animal Studies, Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Peace Studies Journal, Green Theory and Praxis Journal, Save the Kids, Arissa Media Group, and Poetry Behind the Walls. We would also like to thank all of the contributors, Anne C. Bell, Constance L. Russell, Karin Gunnarsson Dinker, Helena Pedersen, Sean Parson, Meneka Repka, Richard J. White, Anita de Melo, and William E. Shanahan III. We would also like to thank nonhuman animals, Animal Liberation Front and Animal Liberation ACT, and radical educators everywhere. John would like to acknowledge the human and nonhuman members of his family, the students and faculty in the Cultural Studies and Social Thought program at Washington State University, the radical activists sacrificing life and freedom for liberation, and all the radical activist-educators fighting in classrooms and communities to abolish the logics of domination pervasive in schools. Anthony would like to thank Becky, Carey, Mark, Dawn, Keri, Kate, and Janine in the Department of Sociology at Fort Lewis College. He would also like to thank Mari, Chris, Michael, Terry, Jorg, Carlos, Cam, Cannon, Olivia, Logahn, Sierra, Brenna, Arissa, Erik, Chiara, Kara, Damon, Chad, Tracy, Don, Arash, Ahmad, Laurie, Torie, Daniel, Janice, John, Sidney, Kaidee, Emma, MeKayla, Mikayla, Cleo, his family, his professors at Syracuse University, Fresno Pacific University, University of St. Thomas and Jay, Ben, Brian, Jeremy, and many other friends he has organized with throughout the years for social justice! ← ix | x →

Introduction: Examining the Nexus: Critical Animal Studies and Critical Pedagogy

Introduction

Critical animal studies (CAS) has increasingly grown as a scholarly movement over the past decade, after emerging out of critical thinkers who wished to dislodge the tenants of humanism. However, despite its growth, CAS has been conflated with other branches of critical theory and scholarship on speciesism. These other approaches include strictly utilitarian concerns surrounding human–animal relationships, embodied in thinkers like Peter Singer and pragmatic reformist organizations like the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). It also includes approaches that retreat purely into the ontological origins of epistemic constructions of the animal, embodied by Derridean deconstruction and academic scholarship. What distinguishes CAS from other approaches to human–animal studies is that CAS mandates theory be intimately tied to action with the intent of supporting total liberation from an intersectional perspective grounded in anarchism and supporting radical revolutionary direct action such as the Animal Liberation Front (ALF; Best & Nocella II, 2004). This is not to say any action advancing the cause of total liberation will be perfect or uncompromising when performed. At the same time, the endpoint of total liberation for all—both human and nonhuman alike—must not be sacrificed when weighing such concessions. The reasoning is that all too often small advancements for reform turn back the pace of more revolutionary change (Nocella II, White, & Cudworth, 2015). For CAS, advancing the liberation of nonhuman animals through using other human oppression as ← 1 | 2 → an absent referent, or at the sacrificing of individuals with disabilities, is unacceptable (Nocella II, Bentley, & Duncan, 2012). In short, while tactics may vary between CAS scholars, what remains consistent is working to dismantle the exclusionary circles of compassion and fighting against all forms of injustice. CAS is against academia and the academic industrial complex along with all forms of elitism, individualism, competition, capitalism, and exploitation, which academics promote and foster. One does not need to be an academic to be in the academic industrial complex/higher education, but rather a scholar. CAS and the Institute for Critical Animal Studies (ICAS) promote scholar-activists and activist-scholars, who are reflective and critical.

As one model for CAS, ICAS was formed in 2001 by Anthony Nocella II and Steve Best to bring activists and scholars together (ICAS, 2017). In 2007, Steve Best, Anthony J. Nocella, II, Richard Kahn, Carol Gigliotti, and Lisa Kremmerer shared from ICAS principles for a CAS that:

- Pursues interdisciplinary collaborative writing and research in a rich and comprehensive manner that includes perspectives typically ignored by animal studies such as political economy.

- Rejects pseudo-objective academic analysis by explicitly clarifying its normative values and political commitments, such that there are no positivist illusions whatsoever that theory is disinterested or writing and research is nonpolitical. To support experiential understanding and subjectivity.

- Eschews narrow academic viewpoints and the debilitating theory-for-theory’s sake position in order to link theory to practice, analysis to politics, and the academy to the community.

- Advances a holistic understanding of the commonality of oppressions, such that speciesism, sexism, racism, ablism, statism, classism, militarism and other hierarchical ideologies and institutions are viewed as parts of a larger, interlocking, global system of domination.

- Rejects apolitical, conservative, and liberal positions in order to advance an anti-capitalist, and, more generally, a radical anti-hierarchical politics. This orientation seeks to dismantle all structures of exploitation, domination, oppression, torture, killing, and power in favor of decentralizing and democratizing society at all levels and on a global basis.

- Rejects reformist, single-issue, nation-based, legislative, strictly animal interest politics in favor of alliance politics and solidarity with other struggles against oppression and hierarchy. ← 2 | 3 →

- Champions a politics of total liberation which grasps the need for, and the inseparability of, human, nonhuman animal, and Earth liberation and freedom for all in one comprehensive, though diverse, struggle; to quote Martin Luther King Jr.: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

- Deconstructs and reconstructs the socially constructed binary oppositions between human and nonhuman animals, a move basic to mainstream animal studies, but also looks to illuminate related dichotomies between culture and nature, civilization and wilderness and other dominator hierarchies to emphasize the historical limits placed upon humanity, nonhuman animals, cultural/political norms, and the liberation of nature as part of a transformative project that seeks to transcend these limits towards greater freedom, peace, and ecological harmony.

- Openly supports and examines controversial radical politics and strategies used in all kinds of social justice movements, such as those that involve economic sabotage from boycotts to direct action toward the goal of peace.

- Seeks to create openings for constructive critical dialogue on issues relevant to Critical Animal Studies across a wide-range of academic groups; citizens and grassroots activists; the staffs of policy and social service organizations; and people in private, public, and non-profit sectors. Through—and only through—new paradigms of ecopedagogy, bridge-building with other social movements, and a solidarity-based alliance politics, is it possible to build the new forms of consciousness, knowledge, social institutions that are necessary to dissolve the hierarchical society that has enslaved this planet for the last ten thousand years. (pp. 1–2)

Since that time, ICAS has grown into an international organization that hosts annual conferences on several continents while keeping its intersectional focus and call for total liberation alive. While several schools of thought and activists have splintered away from ICAS to find their own niches, ICAS continues to serve as an outpost for new students to enter into and explore how best how to achieve the aim of CAS for themselves. In fact, despite its differences with other individuals and organizations, ICAS could not have come into existence without these perspectives. Their efforts allowed ICAS and its supporters to branch out and explore other avenues for resistance after fracturing apart. In many instances, while the differences are not insignificant, the coalitional benefit of varied strategies outweighs these smaller differences so long as the ← 3 | 4 → principle of a total liberation is upheld as the goal. As Richard Kahn and Brandy Humes (2009) explained:

[T]otal liberation pedagogy, following the advances of multicultural educational theory, views oppression in systematic and complex terms, what Patricia Collins (2000) has termed the “matrix of domination.” This not only allows for a more refined analysis of the ways in which power circulates throughout nature and culture, to the systematic advantage of some and disadvantage of others, but by increasing the number of epistemic standpoints from which to teach and learn we free a potential multitude of educational subjects from the culture of silence generated by the dominant mainstream pedagogical and political platforms. (p. 182)

Therefore, the principle of total liberation requires accepting competing subjectivities even when in disagreement in order to strategize against dominant frameworks and political orientations. The acceptance of seemingly mutually exclusive possibilities can mobilize one to challenge current power structures as long as these differences in approach are individualized and work to disallow such differences to get in the way of an overall strategy of total liberation.

Since falling short is always inevitable, the aim of CAS is not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good or strictly to define what counts as CAS scholarship. Nevertheless, it is important to distinguish CAS from strategies that are fundamentally at odds with total liberation. To this end, CAS is defined by its courage to do more and not succumb to the good as the excuse for not pushing for the perfect. This requires a willingness to reflect on the interlocking matrixes of domination that persist even as we struggle to resist. Despite any setbacks we may encounter, we must be willing to try again tomorrow until we have achieved a world where all are free no matter how long it takes. If along the way, total liberation is abandoned as the primary objective, the struggle becomes disempowered since being good turns into an excuse for being good enough and not doing more. Furthermore, this causes scholarship to lose its critical edge and activists to be co-opted into the nonprofit industrial complex. Put simply, CAS as a field teaches total liberation through the praxis of turning scholarship into activism and turning the actions of organic intellectuals into academic knowledge. To this end, “total liberation pedagogy does not seek to just destabilize human power in the abstract, but roots this in the need to support cultural and political practices that actively seek to overthrow speciesist relations across society” (Kahn & Humes, 2009, p. 182). Hence, scholarship cannot reside in the academy alone. Instead, scholarship must empower those who learn from it to integrate that knowledge into their day-to-day lives as meaningfully as possible. The aim of this book is to do precisely that. ← 4 | 5 →

Sadly, much of the work on critical praxis and social justice that aims for liberation fails to consider non/humans as a subjectivity worth considering. This is unfortunate because, when organizing, it fuels “more profits for the corporations that own or contract with factory farms…[used at] the food services at the hotels at which every social justice conference I’ve ever attended were hosted” (Gorski, 2014, p. 8). Again, to be clear, we recognize not everyone can avoid factory farms and industrial agriculture due to various socioeconomic reasons. However, when organizers promote events at places where vegetarian and vegan options are available at comparable or lower costs, to still serve flesh is giving up on total liberation. Furthermore, the sacrifice of literal lives during an academic event that supposedly calls for social justice is not a minor area of disagreement. Gorski (2014) explained:

There’s a price to pay for sitting atop an abusive industry, and part of that price is representing that industry’s atrocities[, which include being]…the biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the world (Goodland & Anhang, 2009)—bigger, in fact, than all other sources combined. But that’s not all, because the havoc factory farms wreak is varied and extensive, and it targets some of the most marginalized beings in the world. … Farm animals…[are] slaughtered at a rate of about 1 million per hour…[while serving as] a form of violence against humans. (p. 7)

To this end, CAS is an important starting point for organizing around social justice since it includes speciesism within its intersectional understanding instead of leaving it as an afterthought. This is important now more than ever because

we live in a time of a mass species extinction event such as we have not witnessed on the planet for nearly 65 million years. The zoöcidal eradication of unprecedented numbers of mammals, amphibians, reptiles, birds, fish, insects, and other animals that is now fully underway…[driven by] the exponential growth…of the industrial factory farm model of animal agriculture. (Kahn & Humes, 2009, p. 182)

If one were to ignore these facts, then any progress made by activists would be locked into a spiral of inevitable failure that only strengthens the corporate and governmental entities that solidify oppression in the first place. The goal of CAS in general and ICAS specifically is to ensure that doesn’t happen.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 212

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433134357

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433157882

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433157899

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433157905

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433134340

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14204

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (April)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Vienna, Oxford, Wien, 2019. XII, 212 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG