Kantor: Non/Presence

Summary

Zbigniew Majchrowski, University of Gdansk

The monumental monograph testifies not only to Fazan exceptional erudition but also her deep personal commitment to the study of Kantor’s oeuvre. Reaching far beyond theater studies, Fazan’s reference-rich analysis can be appreciated by those involved in art history, photography, stage design, architecture, and memory studies.

Marcelina Obarska, Culture.pl

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction: Returns, Afterimages, Palimpsests

- 1. Cricoteka: An Archive and Theatroteque

- 2. The New Cricoteka: An Architectural Project

- 3. Performing Art: Events and Exhibitions

- 4. The Universe of Remembering and Forgetting

- Manifestation

- I. Form as a Battlefield

- 1. Political Shades of Autonomy

- 2. Art as a Strategy for Engagement

- 3. The Reality of Shock

- 4. The Aesthetic State and Individual Existence

- II. Theatrical Expansion of Cruelty

- 1. Theatre-trap

- 2. Machines of Violence

- 3. Sadism, or the Expansion of Creative Consciousness

- 4. Relation as a Principle of Cruelty

- 5. Expositions of Affect

- III. The Power of a Melancholic Aura

- 1. The Dramaturgy of Bereavement

- 2. The Dead Past in the Theatre of Memory

- 3. Between Renewal and Loss

- IV. Today Is My Birthday as a Mise En Abyme

- 1. Theatrical Rehearsals: Studies, Sketches, Repaintings

- 2. Painting Methods and Genres on Stage

- 3. Images as Frames and Rehearsals as Parergon

- 4. The Painting Studio: the Iconoclasts’ Visit and the De(con)struction of Death

- Confrontation

- V. The Wanderings of Odysseus: Kantor–Wyspiański–Grzegorzewski

- 1. Repetition and End

- 2. Return as ‘the Impossible’

- 3. Creation as Confrontation and Relationship

- 4. Aura of Renewal

- VI. Kantor/Schlemmer: Harmonies and Dissonances

- 1. Show Rhythm

- 2. Antagonisms and Correspondences

- 3. Unveiling of Experiments

- 4. Postscript to an Expository Narrative

- 5. Progress Versus Internal Evolution

- 6. Material/Non-material as Theatrical Mediation

- VII. Maria Jarema/Kantor: The Art of Relationships

- 1. ‘Let’s Anticipate, let’s anticipate’

- 2. ‘The Modern Woman: the Mona Lisa of the Twentieth Century’

- 3. Two Theatres, Two Cuttlefish

- 4. ‘Let’s Go Together, My Dear Man.’

- VIII. Kantor vs. Bereś: Emballages and Exposure

- 1. Happening: Between Form and Event

- 2. Kantor/Bereś: Co-presence

- 3. Bereś: Manifestation, or the Politics of Openness

- 4. Kantor: The Hidden, or Aesthetics as Politics

- 5. Difference, Reconciliation, Separation

- IX. The Phantom of Anatomy vs. Critical Corporeality

- 1. The Body: The Outside of the Inside

- 2. The Body’s Veils

- 3. The Body Shattered

- 4. Thanatological Strategies: Between the Symbolic and the Real

- Traces

- X. Scenographies for Official Theatres on the Stage of Memory

- 1. Tadeusz Kantor as Decorator and Costume Designer

- 2. Objectified Costume and the Organic Revision of Materiality

- 3. Costume: A Shell for an Actor’s Metamorphosis

- XI. The (Final?) Role of Costumes

- 1. Costumes Come Out of Storage

- 2. The Digital Catwalk of Theatrical Fashion

- 3. Body/Costumes

- 4. The Destructive Condition of the Costume

- 5. The Secretiveness of Dead Matter

- XII. Machines and Objects in Museum Space

- 1. Dormant Objects

- 2. Things and Words

- 3. Soulless Automatons and Phantoms of Destiny

- 4. The Funeral Machine, the Anti-Machine and the Perverse Trap

- 5. Theatrical Props and Their Doubles

- XIII. Photographic Archive: The Machine of Memory and Death

- 1. Photographs: Images of (Un)memory

- 2. The Paradox of Storage: Archival Wardrobe for The Dead Class

- 3. The Dead Class: From Rehearsal to Touring

- 4. Today Is My Birthday – Rehearsals, Negatives, Exhibitions

- 5. The Posthumous Life of Photography

- XIV. Kantor’s Face

- 1. Necessity of the Face

- 2. Photography as Stage and Autobiography

- 3. Self-portrait: The Mask and Its Silent Speech

- 4. Theatre as a Site of the Face

- 5. Reclaiming the Face: Between Idol and Person

- XV. Strong (Omni)presence and Its Apparitions

- 1. Absence: Paradoxes and Inspirations

- 2. Return to Presence

- 3. Translocations of ‘I’: From Image to Film

- 4. The Concept of Being Oneself

- 5. The Privatisation of Presence

- (Digression: A Quasi-Erotic Relationship)

- 6. The Tyranny of Presence

- 7. Presence as a Role

- 8. Non/Presence and Exposure

- Illustrations

- Selected Bibliography

- Index of Names

- Series index

Katarzyna Fazan

Kantor: Non/Presence

Translated by Thomas Anessi

Copy editing by Grupa Mowa

Berlin - Bruxelles - Chennai - Lausanne - New York - Oxford

Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress.

The publication is financed by the state budget as part of the program implemented by the Ministry of Education and Science called “National Programme for the Development of the Humanities”, project no. NPRH/U21/SP/508119/2021/11, financing amount PLN 102 158.00, total project value PLN PLN 102 158.00 (Poland).

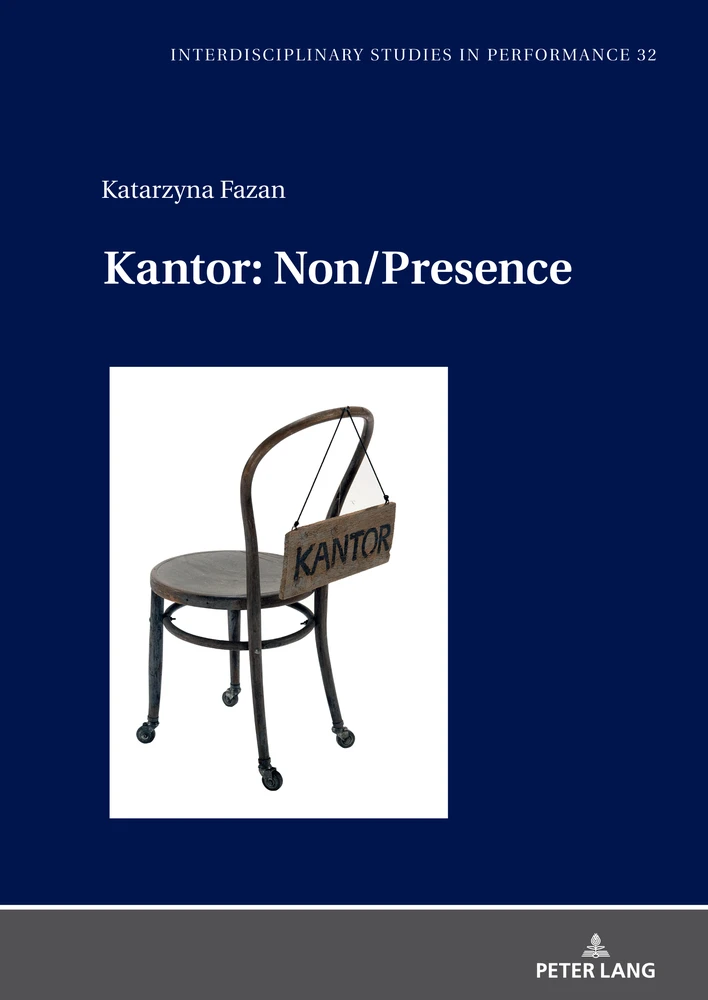

Cover image courtesy of Ewa Kulka. The Artist’s chair’ is an object from the production Let the Artists Die (the chair of Tadeusz Kantor).

ISSN 2364-3919

ISBN 978-3-631-87411-0 (Print)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-92884-4 (E-PDF)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-93066-3 (EPUB)

DOI 10.3726/b22559

© 2025 Peter Lang Group AG, Lausanne Published

by Peter Lang GmbH, Berlin, Deutschland

info@peterlang.com - www.peterlang.com

All rights reserved.

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright.

Any utilization outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution. This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming, and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

About the author

Katarzyna Fazan is Full Professor of Theatre and Drama at the Jagiellonian University and the State Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków, Poland. Her research focuses on modernist literature and theatre, along with contemporary visual arts and scenography. She co-edited Tadeusz Kantor Today: Metamorphoses of Death, Memory and Presence (Peter Lang International Academic Publishing, 2014) and A History of Polish Theatre (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

About the book

Kantor: Non/Presence is a unique work in theatre studies by a single author. The book far exceeds the framework set by its eponymous protagonist. Fazan reveals where following Tadeusz Kantor can lead and how radically the discourse of theater studies should be transformed in contact with his vast, heterogeneous oeuvre.

Zbigniew Majchrowski, University of Gdansk

The monumental monograph testifies not only to Fazan exceptional erudition but also her deep personal commitment to the study of Kantor’s oeuvre. Reaching far beyond theater studies, Fazan’s reference-rich analysis can be appreciated by those involved in art history, photography, stage design, architecture, and memory studies.

Marcelina Obarska, Culture.pl

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Introduction: Returns, Afterimages, Palimpsests

Kantor still remains among us

– Jan Kott, Kaddish: Pages on Tadeusz Kantor1

1. Cricoteka: An Archive and Theatroteque

In hindsight, we can view the passing of Tadeusz Kantor as a dramatic phenomenon, full of contradictions and entangled in a web of tensions and paradoxes. As an artist, Kantor was exceptionally sensitive to eschatological notions. He used mental and visual techniques and archiving strategies to cultivate his premonitions of death, and thus, his own non/presence. He believed in the metaphysical value of art and predicted that his own demise could mark the start of a new life. This prediction came true: Kantor’s legacy endures in dynamic and passive forms of expression. His legacy is not only highly valued, but also actively engaged in various creative and parasitic acts. It manifests itself in confrontations with the past, which attests to the importance of revindication, so highly valued by the artist himself, as well as in attempts to challenge or even negate his position. The enduring traces of such a person and their work post-mortem provide a unique research challenge, one that is inextricably tied to original projects, anticipations, clichés and reinterpreted in new contexts, unanticipated by Kantor himself due to the limitations of his own personal intellectual and historical perspectives. This volume approaches his art from several perspectives as a means of demonstrating its potential – at once strong, confrontational, demonstrative and weak, disempowered by the passage of time and cultural change. The starting point for these encounters with the artist’s work is an analysis of the use of the name ‘Cricoteka’ and Kantor’s name itself in cultivating different forms of memory that lie at the heart of his art and its documentation. This proves all the more important for my research as my thoughts on the artist have developed gradually, in part through visits to Kantor’s archive in its contemporary context at a turning point for Cricoteka itself: during its move from Kanonicza Street in Kraków to a modern museum built on Nadwiślańska Street.2 Therefore, it seems crucial to first consider both what this place of memory was in the past and what it has now become.

The Centre for the Documentation of the Art of Tadeusz Kantor Cricoteka embodies an artistic project but also a practical challenge, conceived of and designed by the artist himself. When, in the early 1980s, the opportunity arose to secure a permanent residence for the Cricot 2 theatre, Kantor divided up the future site of the theatre and museum-cum-archive into four sections serving different functions. He imagined it as a place for accumulating the past, while at the same time remaining alive and open and constantly evolving. The first section, dedicated to the visual sphere and designed as a space for play with the past, was to house an exhibition featuring a collection of reconstructed stage situations. The second, no less important, section was devoted to research and archival work: in it documents were to be collected and organised according to Kantor’s precise guidelines. It would also serve as a study space for both individual and collaborative research. Another section was designed as a didactic space for lectures, studies and discussions. The final section was conceived as a venue open to everyone, where living cultural events could be hosted.3

The project gradually came to life, first conceptually, then on paper, and finally in reality in the Cricot 2 theatre’s cramped quarters on Kanonicza Street, its first home after leaving the Krzysztofory Palace. As it developed, it also changed, accruing little by little new, updated objectives and functions. In many of Kantor’s texts, the archive emerges as the central element of his vision. In a sense, the concept of an artist being limited to their art precedes and anticipates artistic, historiographic and philosophical contemplation of the idea of preserving art’s past in the form of tangible and intangible traces. This desire arose from both Kantor’s own personal artistic experiences and from his artistic practice and collaboration with other artists in the 1960s and 1970s, which were oftentimes ephemeral, leaving behind documentation rather than artefacts. Moreover, it served as a prelude to his theory and concept of preserving artistic forms and remembering them in their dynamic states. These ideas were shaped by an awareness of the original meaning of the Theatre of Death, but also the theatre of memory, as noted by the artist. Kantor assigned to the archive the task of accumulating the past, but he wanted this place of memory to be open to unforeseen future scientific and artistic developments as well:

The Archive of the Cricot 2 Theatre Centre has a dual role: AS A MUSEUM

and A RESEARCH INSTITUTE.

These two functions are combined in the main section of the Centre: THE ARCHIVE.

The Archive is most closely and directly connected to the work of the Cricot 2 Theatre. It is the sole guarantor of THE WORK’S SURVIVAL, ITS PRESERVATION IN THE SOCIAL CONSCIOUSNESS, /

ITS TRANSMISSION in A DYNAMIC STATE TO FUTURE GENERATIONS.4

Established in 1980, Cricoteka on Kanonicza Street was an important space for the theatre’s continued functioning, but did not offer security in terms of its future. This lack of a permanent home mainly effected its staging practices, but as a workspace for accumulating words and objects Cricoteka also functioned as a Theatroteque, a theatrical repository. Conceptually, the space merged two traditions: the modern notion of art as documentation and the classical-philological concept of the art of memory (ars memoriae), involving the rhetoric of places, iconography and texts. Kantor often combined different traditions, and he frequently returned to his original sources, invoking his classical education at a pre-war secondary school. The art of memory grows out of this distant humanist past, shaping the imagery of written forms in both the rhetorical sphere and theatrical space, and becoming intertwined with painting and the performing arts. Kantor often made use of such mnemonic techniques, drawing on cultural resources. However, he re-envisioned the associated meanings and images, giving them his own personal stamp. In the four productions created in the early 1980s, after the move to Kanonicza (Wielopole, Wielopole, Niech sczezną artyści [Let the Artists Die], Nigdy tu już nie powrócę [I Shall Never Return], Dziś są moje urodziny [Today Is My Birthday]), he combined personal themes with historical events. The latter two productions also became mental narrations which, as if they were living museums, used performance to harken back to other productions by Kantor, from the wartime Powrót Odysa [The Return of Odysseus], to Witkacy’s Kurka Wodna [The Water Hen] and Wielopole, Wielopole, based on Kantor’s own script.

In Kantor’s written and recorded intuitions, Cricoteka on Kanonicza Street ‘mapped’ other places of importance to him onto the topography of Kraków. He used this memory map of ‘his art, his journey’ to link places in Kraków with the titles of his productions and stages of his artistic journey. These included the Ephemeral and Mechanical Puppet Theatre and The Death of Tintagiles by Maurice Maeterlinck (staged before the war in the Bratniak student club), the Underground Independent Theatre (on Szewska and Grabowskiego Streets, where he staged Słowacki’s Balladyna and Wyspiański’s The Return of Odysseus), the Artists’ Theatre (the post-war staging of Mątwa [Cuttlefish]), the Informel Theatre, the Zero Theatre, the Happening Theatre, the Theatre of Death and performances of Witkacy at the Krzysztofory Palace on Szczepańska Street, and finally, Cricoteka as a concrete space at the foot of the Wawel Royal Castle, where he held performances from the 1980s onward. Kantor used the archival materials on Kanonicza Street to create an imagined map, returning to places from his memory, recreating their topographic and material features as he remembered them and using language to merge time and space. He supplemented this verbal expression in his theatre with material objects. He also drafted a legend for the map, rich in multigenre descriptions of his creative strategies. He recorded everything, carefully organising the collected material and constantly supplementing his past performances and artworks with new texts.

From Cricoteka’s first days, Kantor invoked the historical tradition of the ‘artist’s portfolio,’ which could include paintings, sketches, drawings, drafts, texts and written compositions, assembled in a loose, patchwork arrangement open to changes and additions. Yet, Cricoteka was also a material space, and Kantor had to contend with the demands of its architecture. The historical, medieval-era tenement house on Kanonicza contained two rooms on the ground floor separated by a wide hallway, as well as a basement. Each room was utilised for some form of creative activity, archiving or storage, and provided space to hold exhibitions, meetings, discussions and rehearsals. The building resembled a warehouse that was occasionally used as a gallery space, or a studio that doubled as an office for a writer who was also his own secretary. The interiors demanded creative solutions and inspired Kantor both as an author and as a constructor, creating props for new performances and reconstructing stage objects used in the past. Sometimes replicas, these objects were assigned their own inventory numbers and added to the archive. A practice of assigning labels to them (an act I will refer to as ‘the archaeology of things and their new reality’) redefined their former and future functions and situated past meanings and future spectral destinies within a post-theatrical narrative. This practice was accompanied by not only a strong sense of the ephemerality of theatre (questioned nowadays), but also by a need to make tangible ideas from the past, which, like some form of regenerative karma, proved vital to Kantor in the creation of new incarnations of his art. His passion for casting off consumed forms revealed itself in a tendency to employ modernist repetition, while clichés of memory provided non-identity material structures of traces of the past. The reality of past theatrical forms was replaced by objects and their names, to which the artist attached great importance, cultivating something like a cult of proper names and his own signature terminology. Objects had the names of theatrical props permanently affixed to them, designating their ontology in time and space. These quasi-curatorial inscriptions marked the horizon of an undefined future.

Actors constituted another important part of the Cricot 2 milieu, and although Kantor often replaced them with mannequins both in the theatre and on the ‘stage of the archive,’ likenesses of them were placed in the sections dedicated to the artist’s collections of photographs and portraits, thereby linking the names of characters from the Cricot 2 theatre with the performers who played them. Photographs from Umarła klasa [The Dead Class], for which Kantor initially designed a special chest of drawers, were pasted onto small black boards with inscriptions on the back. Certain drawers held photos from other performances, others contained reviews and various other texts about the Cricot 2 theatre. Narratives of Kantor’s post-dramatic theatre were stored in black file folders along with a whole library of drafts, music scores, descriptions and texts concerning his creative genealogy and inventions.

Details

- Pages

- 472

- Publication Year

- 2025

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631928844

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631930663

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631874110

- DOI

- 10.3726/b22559

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (December)

- Keywords

- history of theatre philosophy of art aesthetics modernism postmodernism the ideology of progress in art avant-garde painting archive Cricoteka Tadeusz Kantor melancholy memory photograph pictures video collection

- Published

- Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, New York, Oxford, 2025. 472 pp., 29 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG