Métis Coming Together

SHARING OUR STORIES AND KNOWLEDGES

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

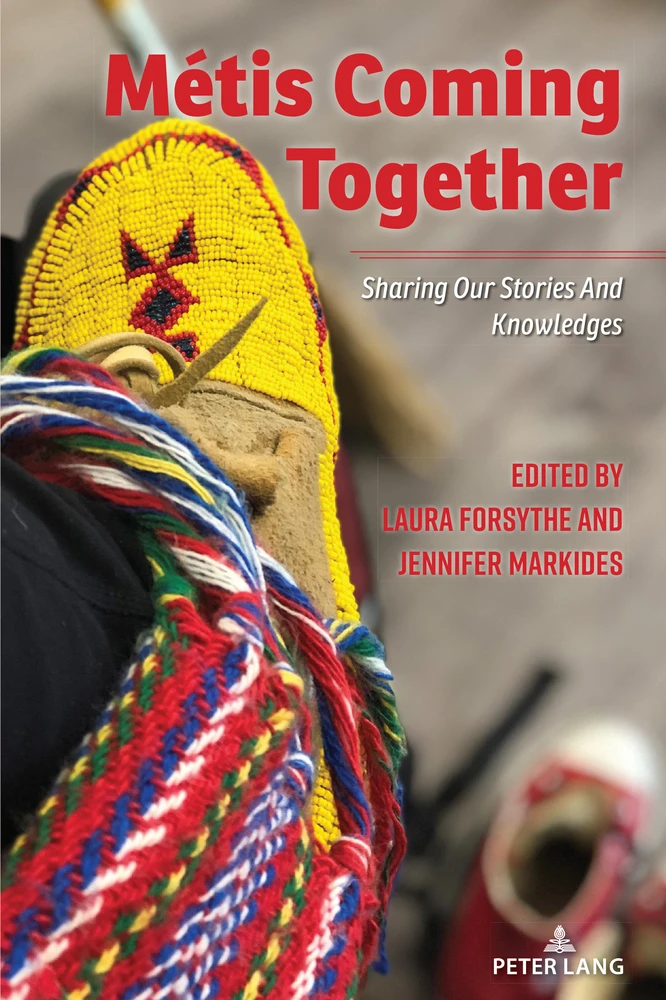

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Foreword (Chelsea Gabel)

- Introduction: Multifaceted Métis: Unavoidable Considerations Around Our Complex Identities (Jennifer Markides and Laura Forsythe)

- 1 The Reason We Gather: Métis-Specific Spaces (Laura Forsythe and Lucy Delgado)

- 2 Red River Readers in Multivocal Flux: Across, Between, and Beyond Traditional Disciplinary Approaches to Métis Studies (Red River Readers)

- 3 The Power of Dancing in Two Worlds: Finding a Fit for Métis Identities in Academia (Shannon Leddy)

- 4 The Métis Nation, Epistemic Injustice, and Self-Indigenization (Kurtis Boyer and Paul Simard Smith)

- 5 Returning to Ceremony: A Métis Spiritual Resurgence (Chantal Fiola)

- 6 Archaeology with Our Ancestors: The Exploring Métis Identity Through Archaeology (EMITA) Project (Kisha Supernant, Emily Haines, Solène Mallet Gauthier, Maria Nelson, Eric Tebby, William T. D. Wadsworth and Dawn Wambold)

- 7 On Being Elsewhere to Stay: Reflections on Métis Responsibilities Living in the Homelands of Other People (Robert L. A. Hancock)

- 8 “It’s Very Different Walking in Two Worlds as a Métis Person”: Identity, Community, Culture and Connections as Determinants of the Health and Wellbeing of Métis Peoples (Heather Foulds, Jamie LaFleur and Leah Ferguson)

- 9 The Grandmothers of the Prairies to Woodlands Indigenous Language Revitalization Circle (Laura Forsythe)

- 10 Li Keur, Riel’s Heart of the North, an Artistic Narration of Métis History through Peoplehood: Addressing Métis (mis)Recognition and Recentering Métis Women (Suzanne M. Steele, with an introduction by Nicole Stonyk)

- 11 Métis Arts as Education: Visual Storytelling, and More, in Alberta (Yvonne Poitras Pratt and Billie-Jo Grant)

- 12 Raindrops, Fiddles, and Tall Tales: Navigating Our Diversity Through Storytelling (Angie Tucker)

- 13 Learning to Listen Closely: The Listening Guide and “I Poems” in Métis Research Methodologies (Lucy Delgado)

- 14 I Could Turn into a River When I Was a Girl: Crooked Methodologies and the Gathering Research Framework (Michelle Porter)

- 15 Storying Métis Sexualities: Métis Confessions: Our First Time—Red River Edition (Angie Tucker, KD King (Sangria Jiggz), Tanya Ball and Paul L. Gareau)

- Series index

Foreword

Chelsea Gabel

Who are the Métis? Are you really Métis? How Indigenous are you really? These are questions often directed at and about Métis people. Such questions continue to be asked as ways to affirm or challenge our experience of being or our right to exist in relation to First Nations and Inuit peoples. At the same time, we have seen a ripple effect of non-Métis claiming to be Métis while asserting our identities to increase their own connections to the land and resources. Coupled together, these thoughts and actions have helped obfuscate Métis identity and experiences of being.

I would be remiss in writing a foreword for a book on Métis identity without declaring my own. I am Métis from Rivers, Manitoba, and spent much of my childhood and youth in Winnipeg—the heart of the Métis homeland—before moving to Ontario, where I currently reside and work as a professor in the Department of Health, Aging and Society and the Indigenous Studies Department at McMaster University in Hamilton. I am a Desjarlais, a Fleury, and a card-carrying citizen of the Manitoba Métis Federation (MMF). My role in identity debates and spaces is deeply personal, as I was part of the small group of mostly Métis academics who filed a complaint of research misconduct against Carrie Bourassa in 2021. The news of Bourassa’s identity fraud caused tremendous sadness, hurt, and feelings of betrayal, especially within the Métis community. Little did we know that the complaint and the CBC news story that followed would change identity politics in this country forever. In her interview with Robert Henry on Indigenous identity fraud, Caroline Tait (2023) argues that “what we need is a stronger collective voice” (p. 92). Thus, the arrival of Métis Coming Together by Jennifer Markides and Laura Forsythe is particularly timely and even more critical because it fulfills the mission in its title; it brings a strong collective Métis voice from those who have generously shared their knowledge and experiences about what it means to be Métis.

In Canada’s body politic, Indigeneity is largely understood through a First Nations lens based on fragmented and often fictional understandings of the Indian Act (Kelm & Smith, 2018). Centering Indigeneity in the Indian Act erases Métis lived experiences and realities (Gaudry, 2018) including those of land dispossession (Teillet, 2019), the residential school system (TRC, 2015), the Sixties Scoop (Stevenson, 2019), and the half-breed scrip system (Graham & Davoren, 2015). Métis histories are most often framed around the Red River Resistance (1870) and the Northwest Resistance (1885). This perspective omits the distinct experiences of Métis histories such as Métis farms (Barron, 1990), Road Allowance communities (Barron, 1990; Quiring, 2003; Teillet, 2019), and Métis settlements (Mcdougall, 2017). The exclusion of Métis experiences from the broader Indigenous discourse has caused Métis to have to fight for recognition in any number of spaces, including academic spaces, that were created to include them under catch-all terminology such as “Aboriginal” and now “Indigenous.” The effects of these experiences continue to implicate Métis not only intergenerationally but also politically. Our complex history and lack of recognition require understandings that extend beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to Indigenous relations and reconciliation, including recent efforts pointing to the need for distinctions-based approaches that honor the unique needs, experiences, and circumstances of the Métis (Nychuk, 2024).

The dominant narratives in Canada regarding the Métis center on historical and legal interpretations of Métis rather than an exploration of how Métis understand themselves in contemporary contexts. Colonization and settler colonialism have impacted how some of us have come to relate to our Métis identities, families, and communities. Some are forced to hide in plain sight as a form of protection, while others have continued to publicly fight for Métis rights. In all cases, Métis understandings of being have been and continue to be passed down intergenerationally, emphasizing our connections and distinctions as a people. Métis life is complex, yet at the same time it is simple. Métis Coming Together looks to address that reality by providing insights into the various ways in which Métis people understand and express their identity today. This book further seeks to engage in research that is meaningful to Métis people and the communities they live in today.

In the powerful chapters that follow, readers will encounter a rich tapestry of stories, insights, and reflections that shed light on the diverse experiences of Métis people. We are neither the forgotten people that has so often been portrayed nor a mixture of First Nations and Europeans. Métis Coming Together honors the bravery, resilience, and strength of our people and is a testament to Métis people who have overcome adversity with grace, dignity, and unwavering determination. These are the stories of the Métis.

IntroductionMultifaceted Métis: Unavoidable Considerations Around Our Complex Identities

Jennifer Markides and Laura Forsythe

This was not supposed to be a book about identity. It never is. However, everything we write about Métis people—our histories, experiences, epistemologies, methodologies, and lives—speaks to who we are. Métis identity and Métis-ness imbue the work in this collection, Métis Coming Together.

We begin by positioning ourselves, the way many of the book’s chapters do. Many Indigenous scholars have explained the importance of this practice, as it brings us into relationship with each other and situates us in relation to our families, communities, contexts, and places (Absolon, 2011; Absolon & Willett, 2005; Adese et al., 2017; Graveline, 2000; Kovach, 2009, 2017, 2021; LaRocque, 1975; McGregor et al., 2018; Moreton-Robinson, 2017; Smith, 2012). In many cases, we find cousins or distant relations. Those who are knowledgeable about the family names associated with different locations will know how your Métis family fits into the larger fabric of our shared history. Because our Métis identity is often misrepresented, misunderstood, and at times co-opted, knowing and stating our family connections becomes a validating and member-checking process for being Métis.

As co-editor of this collection, I, Jennifer Markides, am honored to be entrusted with the contributions in this book. I am a recognized member of the Métis Nation of Alberta. Despite having citizenship, for a long time I felt a sense of not belonging in our Métis circles. I would share my family names of McKay, Favel, Ballendine, Linklater, and McDermott and rarely hear a connection. Only in the last year was I at a Métis scholar gathering and had a family story shared by Anna Corrigal-Flaminio. I found kin. The sensation of that moment was equal parts excitement, validation, and relief. The scrutiny we face in academic positions is justified and rigorous, yet also terrifying. We do not want to be mistaken or proven not to be Métis. What other scholars live like this? It is a constant cloud that looms in every space. Hiring committees are navigating the identity politics, universities are implementing newly hatched policies, and ultimately Indigenous scholars and staff are taxed with policing who is and who is not Indigenous—faculty, staff, and students alike. It is complicated but necessary considering the climate of pretendianism and fraud. Ugh.

Laura Forsythe d-ishinikaashon. My name is Laura Forsythe. Ma famii kawyesh Roostertown d-oshciwak. My family was from Rooster Town a long time ago. Anosh ma famii Winnipeg wikiwak. Today, my family lives in Winnipeg. Ma Parentii (my ancestors) are the Huppe, Ward, Berard, Morin, Lavallee, and Cyr. Niya en Michif. I am Métis from the Red River Settlement, and I grew up in the heart of the Métis Homeland, like the generations of women before me. My maternal great-grandmother Nora Berard was born in Rooster Town on land known as lot 31, owned by my ancestor Jean Baptiste Berard, and my lineage includes Joseph Huppe, who fought in the Victory of Frog Plain. I am a citizen of the Manitoba Métis Federation. This is my positionality and community connection statement. It is who I claim to be and who claims me.

Beyond positioning, many aspects of identity come to the fore in this book. Some are explicit, and some are tacit. To be clear, there is no singular Métis identity. We are not simply Métis by virtue of being born of an Indigenous and settler union. Métis are a distinct people, as recognized by the 2016 Daniels v. Canada decision. Historically, we became a people with our own language (Michif, with many regionally influenced dialects), culture, tradition, commerce (Shore, 2018), ceremonial practices, stories, governance systems, and political movements. Some of these aspects of our identities—in past and present contexts—are discussed in the chapters that await the reader. These terms do not bind us in the present day. Identities are complex and not measured by blood quantum, place, language retention, or simply enacting cultural tropes. We are modern-day Métis and embody multifaceted manifestations of Métis-ness.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 204

- Publication Year

- 2025

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034354028

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034354035

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034354042

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783034353205

- DOI

- 10.3726/b22355

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (December)

- Keywords

- Métis sovereignty relationality kinship history storytelling language revitalization poetry futurities sexuality feminisms geographies religion and spirituality self-determination Métis Coming Together Sharing our stories and knowledges Jennifer Markides Laura Forsythe

- Published

- New York, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, Oxford, 2025. XII, 204 pp., 1 b/w ill., 6 col. ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG