'Getting the Words Right'

A Festschrift in Honour of Eamon Maher

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

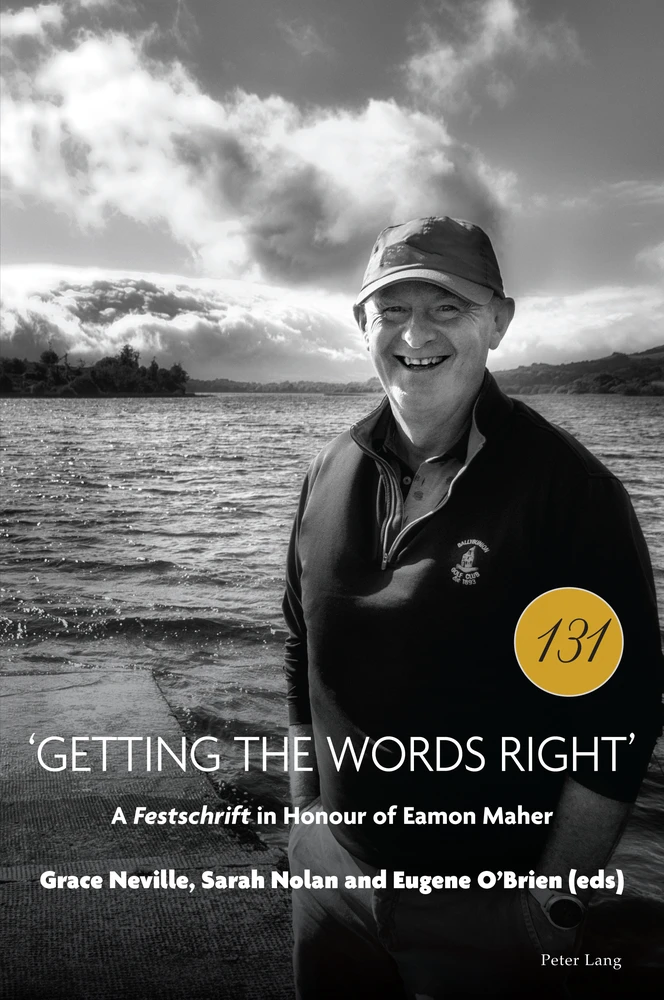

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Une Femme Libre: Edna O’Brien, A Wild Irish Girl in the French Media 1965–2023

- 2 Waking the Living and the Dead: The Revelatory Power of Funerary Rituals in John McGahern’s Late Fiction

- 3 An Intertextual Reading of John McGahern’s Short Story ‘Korea’

- 4 Friendship and Literature

- 5 Elizabeth Bowen’s ‘The Good Earl’: Escaping the Past

- 6 Reflections on the Relationship between Ireland and France

- 7 The Importance of Being Eamon

- 8 French Theory and the Academic Study of Religion in Ireland

- 9 1960–1989: The Making of a Guinness Drinker

- 10 Children in Recent Irish Fiction

- 11 Nuala O’Connor’s Nora and the Challenges of Biographical Fiction

- 12 Judging George Moore’s ‘Wild Goose’: The Case of Ned Carmady

- 13 Trauma and Artistic Creation in Another Alice by Lia Mills

- 14 He Lived among These Lanes: Bioregional John McGahern

- 15 Fifth Business: George Moore and the Cultural History of Music in Ireland

- 16 Transparency and Secrecy in the Poetry of Colette Bryce

- 17 Generous Curiosity: Connections, Community and Commensality in Research

- 18 ‘To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric […]’: Micheal O’Siadhail’s The Gossamer Wall

- 19 Is There a Translator in the Text? Language, Identity and Haunting

- 20 At Someone’s Expense: Nation, Fulfilment, and Betrayal in Irish Theatre

- 21 Writing the Unspeakable in Irish Feminist Life-Writing: Emilie Pine’s Notes to Self and Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat

- 22 Re[p]laying Voices in Translation: Peter Sirr and the Troubadours of Twelfth-Century France

- 23 ‘The Fear of Speaking Plainly’: Translating John McGahern and the Letters of Alain Delahaye

- 24 The Changed Reality of Being a Catholic Priest in Today’s Ireland

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Index

Acknowledgements

The editors are infinitely grateful to all of the contributors for their timely and scholarly contributions – and for not letting the Festschrift cat out of the bag!

GRACE NEVILLE, SARAH NOLAN AND EUGENE O’BRIEN

Introduction

To mark the milestone 100th book in Reimagining Ireland, Peter Lang commissioned a special volume offering both a retrospective on what has been achieved to date in the series, and an outline of future possibilities. Clearly, Irish Studies is a discipline that has blossomed over the past number of decades. One hundred books in a series is a milestone in anyone’s language and the series is now the largest and most significant one in the area of Irish Studies, with multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary focus that ranges across literature, literary and cultural theory, Francophone issues, socio-cultural and political topics and a range of new interactions and intersections across a range of genres.

While it is important to mark the series, we, his colleagues, feel that it is even more important to mark the career and intellectual history of its founding editor, Eamon Maher. The statistics of Eamon’s career are impressive. As a research supervisor, he has graduated some nine PhD and seven Research MA students. He is the founding editor of two series with Peter Lang: Reimagining Ireland which is recognized as the largest Irish Studies series with 125 books in print, and Studies in Franco-Irish Relations which to date has 22 books in print. He has written four monographs and one translation:

The Prophetic Voice of Jean Sulivan (1913–1980) and His Ongoing Relevance in France and Ireland (Dublin: Veritas, 2024 forthcoming);

‘The Church and its Spire’: John McGahern and the Catholic Question (Dublin: The Columba Press, 2011);

Jean Sulivan: La Marginalité dans la vie et l’œuvre (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2008);

John McGahern: From the Local to the Universal (Dublin: The Liffey Press, 2003);

Crosscurrents and Confluences: Echoes of Religion in 20th-Century Fiction (Dublin: Veritas, 2000);

Anticipate Every Goodbye (trans.) (Dublin: Veritas, 2000).

He has edited or co-edited 27 books across a range of literary and socio-cultural topics, and has published some 167 journal articles, 48 book chapters and 63 newspaper articles.

He is a regular contributor of articles and reviews to The Irish Times and journals such as Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review; Doctrine and Life; Irish Studies Review and New Hibernia Review. He is also a newly appointed member of the Comité Scientifique of Études Irlandaises. His work on Franco-Irish academic relations has made him very popular in French diplomatic circles – and in France in general, where he has received the Palmes Académiques and was recently made honorary President of the French Society of Irish Studies (SOFEIR). Clearly, this is a career to be reckoned with and a number of his colleagues felt that it needed to be marked in some way, and for someone who is such a prolific writer and editor, what better way to mark it than with a Festschrift, written by friends and colleagues with whom he has worked across a range of projects over the years. As is clear from these outputs, Eamon has been a powerhouse in the field of Franco-Irish Studies, where he founded the National Centre for Franco-Irish Studies,1 and the Association of Franco-Irish Studies,2 both of which are thriving enterprises with very healthy memberships and a strong tradition of outputs and productions. He is also a world-ranked expert on the work of John McGahern, and he is one of the most knowledgeable contemporary thinkers about the Catholic novel. He also edited some seminal books on the rise and fall of the Celtic Tiger. His work also segues into contemporary culture, and he has written and edited books on the contemporary state of Catholicism in Ireland.

He is also the founder of the Journal of Franco-Irish Studies,3 whose latest edition was published online in 2023. Impressive as these statistics are, they do not capture the drive, imagination and sheer intellectual ebullience that Eamon brings to every project in which he is a participant (or more usually, an instigator). The number of people with whom he has worked across a range of books is huge; their multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary nature is impressive; and the intellectual scope and range of his interests is daunting, as is his postgraduate supervision. As a supervisor, Eamon understands that life, and sometimes babies, can delay the final text production! But he embraces these realities and this allows the student, and research project, to develop. Eamon knows the importance of maintaining a focus on the projected plan, and does this expertly himself, often completing material ahead of time, but he also naturally encourages others to be unafraid to loosen the edges of a subject before pursuing their line of inquiry. The three editors have all worked with Eamon for a number of years and across a range of projects, and are proud to call him a friend. In our opinion, he is one of the pre-eminent figures in what has become a broader notion of Irish Studies, and the books that bear his name will stand the test of relevance and significance as we move through the twenty-first century.

The following chapters in this Festschrift, are all written by colleagues with whom Eamon has worked, and their scope and range is reflective of that broad intellectual sweep that is characteristic of Eamon. The book was written in a very busy semester and the fact that all of these very busy people were happy to be included speaks to the respect and affection in which Eamon is held by his colleagues.

As editors, we would like to thank all of the contributors who have been a joy to work with, and also to thank Eamon himself for his friendship, his kindness, his intellectual energy and his sense of an intellectual community into which he has brought us all in such a productive and enjoyable manner. May his work continue to inspire and elucidate: ut ille vigemusque per plures annos – ‘may he thrive for many more years’.

1 National Centre for Franco-Irish Studies, TU Dublin https://www.tudublin.ie/research-innovation/research/discover-our-research/research-centres/ncfis/ [accessed 9 December 2023].

2 Association of Franco-Irish Studies https://www.tudublin.ie/research-innovation/research/discover-our-research/research-centres/ncfis/about/afis/ [accessed 9 December 2023].

3 Journal of Franco-Irish Studies https://www.tudublin.ie/research-innovation/research/discover-our-research/research-centres/ncfis/about/jofis/ [accessed 9 December 2023].

GRACE NEVILLE

1 Une Femme Libre: Edna O’Brien, A Wild Irish Girl in the French Media 1965–2023

The story of the reception of Irish literature in translation in France is, overall, a remarkably happy one. In recent times, from the early twentieth century onwards, one is struck by the high esteem in which Irish writers are held in France, often more so than in their home country. Colum McCann has always acknowledged French support for him as a young writer just starting out, implying that without it he might have taken a different path and abandoned hopes of a career in literature forever. Even for established writers like Nuala O Faoláin, translations of whose books, especially of Are You Somebody?, became best sellers in France, French acclamation was an enormous boost even at an emotional level: according to her French publisher, Sabine Wespieser, O Faoláin had always dreamt of being published in France. More recently, the runaway success of Sally Rooney is arguably as significant in France as in Ireland, with her books on prominent display in bookshops right across the country.

The names of some Irish writers have overflowed the literary sphere and entered the public space. In Le Monde, a prestigious publication with a strong arts focus, the Irish writer most frequently referenced since its establishment in the 1940s is Oscar Wilde, with well over one thousand mentions. However, most of these allusions turn out to be fleeting ones – to Wilde’s bons mots or to Wilde as icon. It is as if Wilde has become larger than the sum of his parts, certainly more than the sum of his writings. To date, James Joyce has garnered just over one thousand mentions in Le Monde. Here again, most are ‘second-hand’ ones, for instance, to James Joyce pubs; they surface fleetingly in articles on inter alia Leonard Cohen, Peggy Guggenheim, soccer, rugby and Apple. Similarly, the Frank McCourt most referenced is the billionaire Boston-born owner of OM (Olympique de Marseille), not his Limerick namesake who penned the bestselling Angela’s Ashes.

This is where Edna O’Brien comes in. There are no Edna O’Brien pubs, no ships have been named in her honour, she has no namesakes in the world of French sport! She enjoys fewer mentions, for instance, in Le Monde than Wilde and Joyce, both of whom arguably had an advantage over her in their proximity to the French public since, unlike O’Brien, they had actually lived in France. Nonetheless, from the range, depth and strength of the reception of her work in France, O’Brien emerges as the Irish writer with the consistently strongest presence in France since the 1960s: she is France’s ‘go-to’ writer where Irish literature is concerned.1 This chapter will explore the reception of O’Brien in France down to 2023 with particular emphasis on her latest novel, Girl, published in 2019. It will contend that French reaction to this short novel is significant as it crystallizes well over half a century of consistently positive French commentary on O’Brien. It will argue that from the time that O’Brien was a young writer, her concerns chimed with those of reviewers across the French media who welcomed her as a soulmate long years before her native country ever did.2

When investigating the reception of O’Brien in France, it is difficult to avoid French adulation for her especially over the past decade. On 7 March 2021, at a lavish ceremony organized sous les ors de la République and presided over by French Minister for Culture, Roselyne Bachelot, O’Brien was presented with France’s highest cultural distinction, the rank of Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. Until then, only two Irish people had received this supreme distinction: Seamus Heaney in 1996 and Bono in 2013. The symbolism of the date for the ceremony, on the eve of International Women’s Day, was lost on no one: ‘La décoration a été remise à Edna O’Brien la veille de la Journée internationale des droits des femmes, comme un écho aux valeurs qui ont construit son oeuvre et accompagné tant de femmes.’3 To quote the French Ambassador in Ireland, Monsieur Vincent Guérand: ‘Les liens entre la France et l’Irlande sont très forts en particulier dans le domaine culturel et littéraire. Mme Edna O’Brien à travers sa vie, son oeuvre et ses engagements en est un magnifique exemple.’4 In the summer of the previous year, 2020, O’Brien starred at the opening of France’s leading annual theatre festival, Le Festival d’Avignon, organized in partnership with France Culture, when Maryam, Girl’s main character, was re-imagined by the iconic Barbara Hendricks. In 2019, Girl was shortlisted for no fewer than three prestigious prizes, the Prix Médicis, the Prix Fémina Etranger and the Prix du Roman FNAC. In the event, O’Brien became in that year the first non-French person ever to be awarded the Prix Fémina Etranger not for any one publication but for the totality of her oeuvre. In 2017, she received the Irish Francophone Ambassadors’ Literary Award when the French translation of The Little Red Chairs was selected from a short-list of seven works by a jury of twenty-five ambassadors. At the award ceremony on 23 October 2017, organized in Dublin by the Embassy of Switzerland and the Embassy of Morocco, O’Brien ‘went over her career in a passionate speech before a practically mesmerised audience’, as reported by the French Embassy in Ireland. Nor were her translators forgotten: Aude de Saint-Loup and Pierre-Emmanuel Dauzat were awarded internships at the ceremony by Literature Ireland.

O’Brien is no newcomer on the French literary landscape, however. For well over sixty years now, ‘Mlle Edna O’Brien’ (as she was fetchingly called in Le Monde),5 has been a constant on the French literary landscape. Her first novel was published by Julliard as early as 1960 when she was barely 30 years old. La Jeune Irlandaise (later Les Filles de la Campagne) was highlighted as ‘un ouvrage anticonformiste, irréverencieux mais attirant […] un style qui ne se réclamait pas de maîtres’ in Le Monde as early as 9 May 1965.6 Her later works were snapped up by leading publishers including Gallimard, Presses de la Cité, Fayard, Stock and, since 2010, by Sabine Wespieser. In fact, such is Wespieser’s confidence in O’Brien that she re-published her earlier books originally published by Fayard but which had become unavailable in French, including La Maison du Splendide Isolement (2013), Dans la Forêt (2017) and Tu ne Tueras Pas (2018).

Still now in 2023, O’Brien’s power to captivate leading French reviewers endures. Her 2023 play, Femmes de Joyce, was reviewed on 29 June 2023 in Le Monde by its main editor of foreign fiction, Florence Noiville, as was her 2021 James & Nora, with Noiville going so far as to imply that O’Brien herself was in fact one of the Femmes de Joyce, O’Brien’s great hero. Another reviewer even draws a parallel between Joyce’s work and that of O’Brien: ‘elle-même réputée pour son oeuvre abordant franchement la sexualité’.7 O’Brien features in a recent Le Monde review of Nicole Flattery (born 1989, Le Monde, 25 June 2020) though she is a lifetime older than the young writer under discussion: throughout, she remains the touchstone, the reference point, the year zero, the fons et origo.

The publication in the 2019 rentrée littéraire of O’Brien’s nineteenth and latest novel, Girl, was widely heralded as a major event across the French media. It tells the story of a young Nigerian girl, Maryam, one of several hundred girls kidnapped by Boko Haram in 2014 and subjected to unspeakable sexual, physical and mental violence. As preparation for this book, O’Brien made two research visits to Nigeria in 2016 and 2017, visits facilitated by the Irish Embassy in Nigeria and Médecins sans Frontières, and for which – as Andrew O’Hagan, who later interviewed O’Brien, recounts – ‘she also confessed to having smuggled £15,000 into the country, wads of cash concealed in her sleeves and her underwear’.8

On 5 September 2019, O’Brien’s French publisher, Sabine Wespieser, kindly agreed to meet me in her Paris office to discuss O’Brien and this new novel. The date in question, 5 September, was significant as it was the official launch date of both the English original and the French translation: a rare exploit. Wespieser told me that Girl is quite simply the most remarkable book she has ever dealt with. She said that one of its two translators, Pierre-Emmanuel Dauzat, was so struck by the original pre-published English version that he immediately set aside all other projects to prioritize translating Girl. Hence the coup double of the joint publication on the same day just a few months later of the English original with Faber and the French translation with Wespieser. For Sophie Creuz on the Belgian national TV and radio site, rtbf.be, this joint publication is much more than a question of the alignment of dates or of agendas: for her Girl is ‘d’une telle urgence, d’une telle necessité, d’une telle beauté aussi que ses éditeurs anglais et français ont décidé de le publier en même temps’. In conversation, Wespieser further explained to me that while most French translations are longer than their English originals, the translators of Girl succeeded in matching the English and French texts so closely that the original and its translation perfectly mirror each other length-wise.9

So how has Girl been received across the French-language media? As well as Le Monde, the very varied publications mined in this chapter include Libération, Le Figaro, Lire, Le Canard Enchaîné, La Croix, Le Journal du Dimanche, Télérama, Femme Actuelle, Le Soir, La Déferlante, Axelle Magazine, Transfuge, Le Devoir, Les Echos weekend, Elle, Version Femina, La Vie, Le Matricule des Anges, Livres Hebdo and Pages des Libraires. Though mainly French, some Québec and Belgium sources also figure. To these print sources can be added numerous reviews and discussions of Girl on French radio and television, for instance on France’s leading television books programme, ‘La Grande Librairie’ (France 2, 27 October 2021), or the one-hour interview by France Culture’s Marie Richeux with O’Brien in her London home (Les Girls d’Edna O’Brien, 5 November 2019). At another level, acclamation for Girl flows too from readers and booksellers in towns large and small across France and beyond: Lille, Saint-Etienne, Aurillac, Bordeaux, Yvetot, and Namur.10

A summary of this cornucopia of reviews would be that the best has just got better, with Girl hailed as surpassing six decades of O’Brien’s superb writing. Superlatives abound:

‘superbe et terrifiant […] peut-être son roman le plus puissant’; 11

‘un roman ahurissant […] le plus fort qu’elle ait jamais publié;12

‘texte d’une effroyable splendeur […] livre d’une radicalité extrême’; 13

‘éprouvant et extraordinaire’.14

One reviewer who chose Girl as a highlight of the literary rentrée, advises readers to wake up and hang on: ‘Réveillez-vous et accrochez-vous’.15 For a novel that is so intensely physical, with unspeakable descriptions of the extreme physical violence perpetrated on Maryam and on her fellow prisoners, it is interesting to see that some reviewers – perhaps unconsciously – using physical terms (emphasis added below) to describe it: thus, Girl is:

‘saisissant de vérité, il empoigne aux tripes’; 16

‘ce livre coup de poing, puissant requiem pour une enfance assassinée’; 17

‘un roman dont on ressort cabossé mais pas sans voix’;18

‘250 pages pendant lesquelles le lecteur retient son souffle’;19

The experience of reading Girl is so terrifying for one reviewer that ‘elle appelle une course effrénée pour sortir du cauchemar’.20

Perhaps as an unconscious homage to a writer who, one suspects, takes infinite care à la Flaubert over every handwritten word, every carefully crafted image, French reviews often contain clever plays upon words: ‘Edna O’Brien, L’Eire et la Manière.’21

The quasi-assimilation of Girl into the French literary canon, into the very pantheon of French literature, is frequently implied by references in these review titles:

‘Voyage au Bout de l’Enfer’: a reference to Céline’s Voyage au Bout de la Nuit;

Details

- Pages

- XII, 370

- Publication Year

- 2024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781803741482

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781803741499

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781803741444

- DOI

- 10.3726/b20745

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (June)

- Keywords

- john McGahern drama Franco-Irish literature cultural studies poetry prose Irish Studies

- Published

- Oxford, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, New York, 2024. XII, 370 pp., 3 fig. b/w.