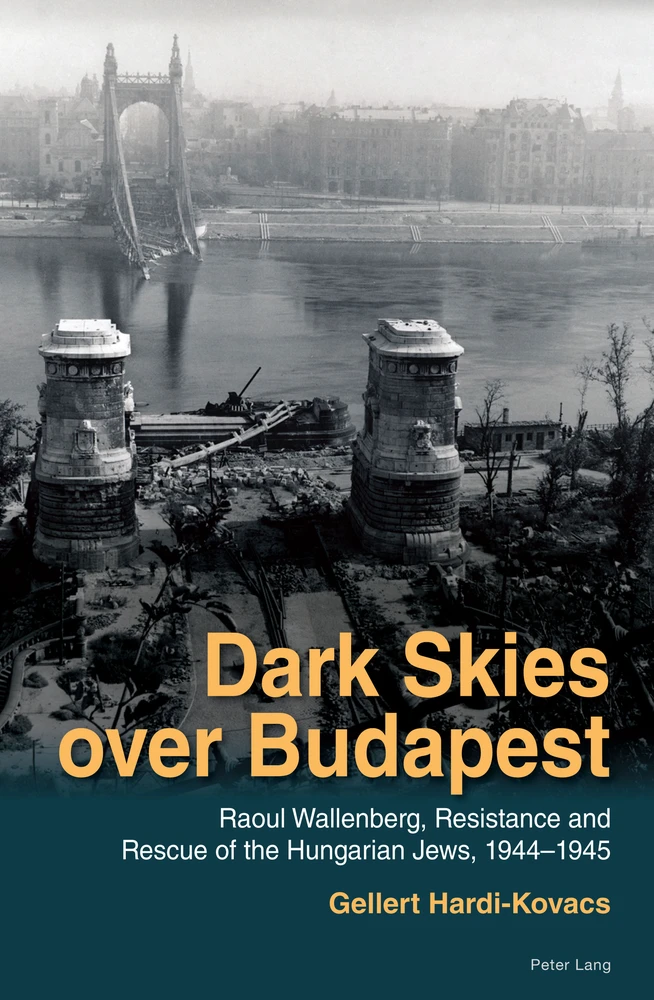

Dark Skies over Budapest

Raoul Wallenberg, Resistance and Rescue of the Hungarian Jews, 1944–1945

Summary

That summer, a young Swedish diplomat named Raoul Wallenberg had arrived in the Hungarian capital, throwing himself into the dramas and intrigues raging in Hungary under the German occupation. Wallenberg soon became an important part of the networks desperately scrambling to save the Jewish population in Budapest. Through Wallenberg’s story, the reader follows the dramatic events that took place between the summer of 1944 and the beginning of 1945 and meets the many individuals and groups that were crucial to this unique and ultimately largely successful action.

Dark Skies over Budapest is a true story of resistance and rescue and of one of the greatest humanitarian efforts of the Second World War. Casting new light on Raoul Wallenberg’s work, the book also tells the story of hitherto unknown but important people – who in many cases never received any recognition for their endeavours – and of actions that have remained undiscovered for many years. This book offers a comprehensive account of what really happened in Budapest in 1944–1945.

Key Takeaways

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations for archives

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Hungary and the Jewish people: A story of love, hate and ambivalence

- The early history

- The ‘golden’ age of coexistence and exchange

- A humiliated nation seeks a scapegoat

- Consolidation

- Economic crisis and social unrest

- Nazism gains ground

- Chapter 2 A pact with the devil

- Entry into the Second World War

- Prelude to the Holocaust

- The disaster at the Don

- Attempts to escape from the war

- A double game

- Chapter 3 1944: The year of darkness

- The occupation

- The deportations from the countryside

- Between confusion and indifference

- Chapter 4 Humanity slowly awakens

- The outside world begins to react

- Resistance in Hungary begins to gain ground

- The MFM

- The Koszorús action

- Chapter 5 Raoul Wallenberg before his posting to Hungary in 1944

- From young boy to citizen of the world

- A man of trade, a Home Guard officer

- Chapter 6 The first period in Hungary

- Building a network

- Intrigues in Berlin and Budapest

- The humanitarian organisation

- Chapter 7 Wallenberg’s first actions

- Chapter 8 Drama in August

- Chapter 9 The situation temporarily stabilises

- Shadow play

- The negotiations with Kurt Becher

- Chapter 10 The planned uprising against the Germans

- The defection agency

- The Hungarian Front

- The Communists

- Jewish groups

- Chapter 11 Taurus and the Swedish courier

- Chapter 12 The two camps plan for a showdown

- Wallenberg’s secret and mysterious contacts

- The intrigues of the Germans and the Arrow Cross Party

- Boiling point

- Chapter 13 Operation Mickey Mouse and Panzerfaust

- Chapter 14 What did Wallenberg do during the coup?

- Chapter 15 An enemy with many faces

- The Arrow Cross

- The gendarmerie

- The police

- The Germans

- Chapter 16 The persecution resumes

- The death marches

- Chapter 17 The neutral envoys

- The Langlets and the Swedish Red Cross

- Friedrich Born and the International Red Cross

- Angelo Rotta and the Vatican nunciature

- Carl Lutz and Switzerland

- Giorgio/Jorge Perlasca and Spain

- Chapter 18 The Schützling Protocol Group

- Chapter 19 The typewriter repairman and the Arrow Cross

- Chapter 20 The resistance rises again

- Chapter 21 KISKA – The secret army

- Chapter 22 Zugló and Angyalföld

- XIV KISKA, the nuns and László Ocskay

- XIII KISKA

- Chapter 23 Wallenberg and the resistance

- Contacts with XIV and XIII KISKA

- Two testimonies

- Chapter 24 The Accountability Unit strikes

- Chapter 25 The action at Józsefváros railway station

- Chapter 26 The siege begins

- Chapter 27 The two ghettos

- The international ghetto

- The main ghetto and its two lions

- Chapter 28 The rescuers work day and night

- Chapter 29 Total terror

- Chapter 30 The bloody Christmas

- The fight for the abducted children

- Chapter 31 The battle for the protected buildings

- Chapter 32 The Nazi serpent’s final bite

- Chapter 33 The massacre in the main ghetto – myth or truth?

- Chapter 34 Epilogue: A story without a happy ending

- Notes

- Postscriptum to the 2024 edition

- Bibliography

- Index

Acknowledgements

First of all, I would like to thank the Ministry of Foreign Affairs fund for independent research on Raoul Wallenberg, whose generous contribution was the ultimate factor in a total of four years of research on the subject and thus also this book. Here I would particularly like to thank my long-standing contact person, Krister Wahlbeck.

Many thanks to Wallenberg expert and former Foreign Ministry employee and Ambassador Jan Lunvik for all the time he spent looking at what I wrote and providing encouragement and constructive criticism. To my friend and colleague Georg Sessler, who has given me a great deal of material, tips, continuous discussions on the theme and a lot of support. You helped me when I sometimes found myself at an impasse with my work. Thank you!

Many thanks also to the staff at the Army Museum in Stockholm for many years of cooperation on the theme. The enthusiastic Tina Nordborg, who has given me so much support and help with contacts. Erik Broberg, Johanna Vaara, Anders Wesslén and Rauno Vaara at the museum have also given me a great deal of support for which I would like to thank them.

The majority of the research was carried out in Hungary between June and November 2009. It was the first time I lived there for a longer period since I left the country in 1982. During my time there, and also later, I conducted several interviews with people I would now like to thank.

Above all, the doyenne of the subject, Szabolcs Szita, who was always helpful, answering my questions and analysing my results and theories. I would like to thank you for all your generosity and advice! Tamás Szabó shared extremely interesting and personal information about his father and Pál Szalai, as well as tips and photos. Thanks to József Gazsi, who in May 2010 agreed to meet with me to talk about his many years of research, despite the grief that had just afflicted him. I carried out interviews with people who had experienced that period: Ernö Nizalowski, Dr Lajos Lugosi, Eva Balla and Pál Fábry. Historians: Tamás Kovács, Károly Kapronczay, György Vámos, László Karsai, Ágnes Godó, András Szécsényi, Krisztián Ungváry and Kálmán Buzási. Thanks to all of you! I would also like to show my appreciation to the staff at the many archives where I have spent hundreds of hours constantly asking for new files: ÁBTL, PTL, BFL, HTL, HDK, Zsuzsanna Toronyi at the Jewish Archives, ZSL. I would also like to thank the staff at the Swedish Embassy in Budapest for their interest and support, not least ambassadorial secretaries Lars-Erik Tindre and Eddy Fonyodi.

Ferenc Orosz and the Wallenberg Association in Hungary have also shown great interest and support.

My time in Hungary was exciting and enjoyable, but also sometimes difficult. I would like to thank all of the friends and relatives there who supported me during that time. I also want to thank the little kitten Mia, who helped me relax with play and mischief as I spent my days reading about human evil. You had a short but happy life.

In Sweden, I would like to express my gratitude to the staff at the National Archives of Sweden and Uppsala University Library’s manuscript collection. I would also like to thank everyone who has shown interest in my research and in various ways helped me during 2012 – the centenary of Raoul Wallenberg’s birth. Many thanks to Ambassador Gábor Szentiványi and Ferenc Bányai at the Hungarian Embassy in Stockholm. Gábor Budai and everyone else at the Hungarian National Association in Sweden. Jenny Nörbeck and Tanja Schult for all the discussions and support. Bo Persson, Albert Libik and Gabriella Kassius for interviews and fascinating conversations. Raoul Wallenberg’s family, with Cecilia Ahlberg as my closest contact. Karin Bornhauser-Wiklund at the Swedish Embassy in Berlin, as well as Ágnes Gelencsér at Haus Ungarn in the same city.

For this edition, I would also like to thank the following persons: Jane Davis who took on the massive assignment of translating the book. My editor Laurel Plapp without whom this book would have never reached the reader. Her commitment to publishing the book during four years of setbacks was completely crucial and truly impressive. Thanks are also due to the following funds for the translation: Kulturrådet (Swedish arts council) and Kung Gustav VI Adolfs stiftelse för humanistisk forskning (King Gustav VI Adolf foundation for humanistic research).

I would like to thank all my friends and family in Sweden who have given me moral support when things have been tough, as well as those who have also helped financially on the occasions when the writing has eaten into the money.

I would like to thank Trygve Carlsson for having published the book in the original Swedish.

For the photographs, I would like to thank Katalin Bognár in the photography department of the Hungarian National Museum, for the time she has devoted to me. Many thanks also to the Deutsche Bundesarchiv in Koblenz, as well as Wikipedia Commons for all the images they have made available for use. Last but not least, I want to thank the people behind the website Fortepan, who posted so many wonderful pictures for general use.

Finally, I would like to thank two people who unfortunately will not be able to read the book.

To my friend Mayah, you always asked how the book was going and showed an interest despite your own problems. You passed away too young, a month after I began writing the book, and you are greatly missed. Thank you for the short time I got to know you.

My father, who passed away after a short illness just a few months before the book came out. It was from you that I got my interest in history and social issues, as well as my love of books. Thank you for everything you gave me. It will always be a sorrow to me that you never saw the finished book.

Last but not least I would like to thank my supporting nearest and dearest; my Mother and my wife Kristina who always support me, on both good and bad days.

Introduction

The aim of this book is to convey new information to the reader about a subject on which much has already been written. This is a book about Raoul Wallenberg and his time in Budapest. But it is also a book about the city where I was born, and about a country that was almost unique in experiencing all of the major currents and events in twentieth-century European history. What happened in Budapest between summer 1944 and winter 1945 was a horrifying episode in European history, but it was also something unique. Because Budapest was the only city in Nazi-controlled Europe where Jewish people survived in large numbers.

Many books have been published about Raoul Wallenberg, particularly in 2012, the 100th anniversary of his birth. Several books were written in the United States during the Cold War, primarily in the 1980s. A number of them discuss his time in Budapest, while others are more interested in his imprisonment in the Soviet Union, and whether he was still alive at the time they were published. Wallenberg grew from a topic of interest for the narrow circle of his family to become almost a legend during the latter years of the Cold War. This renewed interest often had a political objective. It was important to highlight the hero who resisted the evils of Nazism but became a victim of the other evil ideology: Communism. It was during the Reagan years, in the early 1980s, when the Cold War once more heated up, that this current of remembrance was most active and most books were published.

All these books have in common the fact that they lack information about what actually happened in the circles around Wallenberg in Budapest: the Hungarian archives were closed to the authors and until the late 1980s it was taboo to speak of Wallenberg in Hungary. Consequently, these books tend to be based on hearsay and second-hand sources and contain a good deal of myth building. They were often written to align with the American narrative of the endless struggle between good and evil, and the lone, pure hero. Sometimes the real man disappeared amongst all the praise, the myths and political manipulation.

For the avoidance of any doubt, the author of this book would like to emphasise that the aim here is in no way to deprive Wallenberg of his status as a true hero. Quite the opposite. As you read this book, you will discover that he was in every respect a hero, and one of the few Swedes who voluntarily left his protected existence in neutral Sweden and risked his life on a daily basis. The aim is instead to reveal the complexity of the events in Hungary in 1944–5, and of the rescue efforts that meant 130–150,000 Jewish people still remained in Budapest when the Soviet Army took the city, despite the best endeavours of German and Hungarian Nazis to deport and eradicate them. The book aims to show that the rescue efforts were the result of several different networks and corporations between hundreds of people forming an apparatus in which Raoul Wallenberg went from being a newcomer in Budapest to one of the most important cogs. But to see him as the hero he was, it is also important to once and for all dispel the image of the lone diplomat who fooled the simple guards and got them to lower their rifles.

Reality is always more complex, and in 1944 the war, terror and hate raging in Hungary was a reality of the very harshest type …

Even though Wallenberg is the primary theme of the book, the reader will also become acquainted with many of the actors on different sides in the inferno that Budapest became in that brief period. But the unique aspect is that it was a war on three different levels. On the highest level it was one of the apocalyptic battles between the empires of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Alongside this military struggle, there was the war of the Nazis against the Hungarian Jews, which was one of the last but most tragic chapters in the European Holocaust – because it could have been avoided. And finally there was the fratricidal strife between pro- and anti-Nazi Hungarians: a low-intensity and sometimes invisible war, but one no less full of hatred. This ‘war’, which could take the form of passive resistance, sabotage and open conflict, is perhaps the least well known, both in Hungary and on the international stage.

This book will naturally focus on the terror campaigns waged against the Jewish people, and on the attempts to rescue them. The rescue efforts carried out by the neutral organisations in Budapest are now very well known and accounts have already been published, particularly about Wallenberg’s activities. But much of this book will present the secret war between the Hungarians who still believed in a German victory and saw the Jewish people as an enemy to be exterminated and those who, for various reasons, turned against the Germans and attempted to help the Jews in different ways.

The story of the latter group has often been neglected. Some of them were murdered by the Nazis, and even the majority of those who survived were persecuted by the Communist regime in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Many fled the country, while those who stayed often kept their memories to themselves. After the introduction of democracy in the 1990s there was more objective discussion of the war, both on the subject of Hungarian Nazism, but also the relatively small numbers who resisted it. But this movement never achieved a foothold in the broader consciousness, as the public discourse was occupied by the many injuries suffered during the four decades of Communism then coming to an end. Consequently, at the time this book was written, there was relatively little information about these resistance groups and their attempts to oppose the Holocaust. In the eleven years since it was first published, several new books have been written on the topic, but this book is a collective narrative that, perhaps for the first time for an international audience, presents these groups, and the individuals active within them to an international audience and tells how they cooperated with the neutral rescuers.

Just as information about these groups has long been lacking, so has there also been a shortage of books that attempt to penetrate the many myths and present the authentic account of Raoul Wallenberg’s six months in Budapest on the basis of Hungarian archive material. As I have mentioned above, the incorrect assumptions were due to the political taboo in place in Hungary. One of the best books was written by Jenö Lévai as early as 1946, but it disappeared in Hungary after the Communist takeover in 1949. After this, Lévai thought it wise not to mention the subject. The book was also translated into English and Swedish, but these versions disappeared mysteriously soon after they were printed. Exactly why is shrouded in mystery, but it may be related to the fact that, for political reasons, Lévai’s narrative presented the official Soviet account – that Wallenberg had been killed by Nazis left behind the front, between Budapest and Debrecen in eastern Hungary, where he was to meet the Soviet marshal, Rodion Malinovsky. Pioneering work done in the last twenty years by Szita Szabolcs and Maria Ember should also be mentioned. These three historical researchers have had a significant influence on the creation of this book.

The book is divided into several sections. To understand why the Holocaust in Hungary took this particular form, and the environment in which Wallenberg was active, it is necessary to take a brief look at the history of Hungary and its relationship with its Jewish population. I will also provide an account of what happened before the Swedish diplomat arrived, in spring/summer 1944, when an unimaginable 436,000 people were deported – and of the attempts to save them. There is also a short presentation of Wallenberg’s life before he took up his appointment in July 1944.

This is followed by the main narrative of Wallenberg’s time in Budapest, which is divided into several sections. On a general level, this period consisted of three parts: the deceptive calm after the threat to Budapest’s Jewish population was temporarily averted in summer 1944; the time following the Arrow Cross Party’s rise to power with German assistance in October; and finally the siege from mid-December, which was the most horrifying period, with the city’s inhabitants struggling day and night to survive under the most extreme conditions.

CHAPTER 1

Hungary and the Jewish people: A story of love, hate and ambivalence

The early history

In the 1900s, Hungary had one of Europe’s most problematic relationships with its Jewish population. Anti-Jewish sentiment is certainly not exclusive to Hungary, and until the end of the First World War, the country was not notably antisemitic. In fact, quite the opposite. But after 1919 the situation changed, and unfortunately such opinions have once again become more popular in the wake of the political and economic crises afflicting the country since 2006.

In the Roman period, Pannonia, which included the western part of what is now Hungary, was a thriving and important province. As the Jewish people spread across the Roman Empire, they almost certainly also came to Pannonia, not least to the capital, Aquincum, located in the northern area of what is now the Buda side of the Danube.

The first documented proof of a Jewish presence in Hungary dates to the late 1000s, when increasing Christian fanaticism in the German Empire led to migration to the more peaceful country to the east. Hungary had become Christian in around 1000 AD, and the previously warlike Magyar tribes had become farmers in a society that was beginning to stabilise as a feudal kingdom. As far as we know, the attacks that became so common in Western Europe during the First Crusade in the 1090s did not occur in Hungary. However, historical sources indicate that the Crusaders carried out anti-Jewish activities in Hungary as they passed through on their way to Jerusalem.

The 1100s and 1200s produced increasing accounts of a Jewish presence in Hungary. Many fled harsh treatment in Germany and Bohemia to settle in the Hungarian kingdom. At first, they were welcomed, since they brought with them specialist knowledge of crafts and administration through their already high levels of literacy.

As in every other medieval society, the fate and position of Jewish people in the Kingdom of Hungary varied over time, and a shift in attitudes could arise very quickly. The crucial factor was above all the current king’s stance. This could depend on the king’s personal taste and prejudices, but a pattern also emerges. In general, kings with strong positions were more likely to tolerate – and even encourage – a Jewish presence and activity in Hungary. As happened elsewhere, the Catholic Church was often the driving force in demanding a range of discriminatory measures against the only non-Christian minority in Europe.

The strongest Hungarian king, Matthias Corvinus (1458–90) took a significant step towards guaranteeing the rights of Jewish people when he inaugurated a prefecture to defend their rights and to speak on their behalf. Matthias saw that their knowledge, resources and contacts with other countries were important for his far-reaching plans to make Hungary the military, economic and cultural superpower of Central Europe.1

However, Matthias’ premature death brought an end to these plans, and a weakened Hungary became an easy prey for the expansive ambitions of the Ottoman Empire. The weak kings who followed Matthias were encouraged to withdraw the rights previously granted to Jewish people. The Ottoman occupation of Hungary that followed the catastrophic defeat at Mohács in 1526 led to further upheavals for Jewish people – and indeed, for the entire country.

Many Jews fled to the western part of Hungary, which was not occupied by the Turks, while many of those who stayed behind were ordered by the Sultan to move to other cities in the Balkans as a boost to trade. Under Ottoman rule, Jewish people were generally treated with tolerance, in accordance with the Islamic policy of tolerance towards People of the Book. Jews with Sephardic origins – in other words, those driven out of Spain – then began moving to Hungary. These had a more Middle Eastern culture than the European Ashkenazi Jews.

During the almost 140 years of occupation, these Jews became influential, particularly in Buda, and benefited from the Ottoman Empire’s patronage and religious tolerance. At the same time, Jewish people who had fled to the part of the country occupied by the Habsburg forces were suffering. The militantly Catholic House of Habsburg was antagonistic to both the Muslim Turks and growing Protestantism in Hungary, and in their violent counter-reformation viewed anyone who was different as a target. Naturally, this included the Jewish people, who were seen as outsiders.

When the Christian armies of the Holy League under Emperor Leopold I began to push the Turks out of Hungary in the 1680s, the Sephardic Jews, who looked and dressed like Turks, were treated very cruelly. In many cases they were killed on sight, as happened in Buda when it was recaptured in 1686 and where they were massacred together with many of the city’s Turks. When the whole of Hungary had been retaken by the House of Habsburg, a new dark time followed, with many restrictions for the few remaining Jewish people. Despite this, Ashkenazi Jews arrived in Hungary from Bohemia and Austria, seeing opportunities in a country ripe for reconstruction after 150 years of occupation and war. They were also joined by poor Jews from Galicia, a region covering parts of what are now Poland and Ukraine, where there was significant persecution of Jewish people, sometimes leading to full-scale massacres, such as those under the leadership of Bohdan Khmelnytsky in the 1640s and 1650s.

During the reign of Empress Maria Theresa, the situation improved somewhat, but it was above all under her son, Joseph II, that the situation of Jewish people stabilised in the entire Habsburg Empire, including in Hungary. Joseph was an enlightened monarch who wanted to modernise the kingdom, expand human rights, abolish serfdom and limit the power of the Catholic Church. Increased religious freedom and the dismantling of the various special regulations targeting the Jewish people formed an important aspect of these proposed reforms. As one might expect, both the nobility and the Church reacted strongly to these plans, and when Joseph fell seriously ill after just ten years on the throne, he was forced on his death bed to revoke the majority of the reforms he had striven to achieve.2

A period of reactionary politics followed under Emperor Francis II, resulting from pressure by revolutionary France on the Austrian Empire. After the signature of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Austria, Russia and Prussia formed the Holy Alliance to suppress any future revolutionary ideas of human rights. Despite the reactionary regime in Vienna, the decades of the 1820s to 1840s became known in Hungary as the ‘Reform Period’, during which many new ideas about the country’s future were formulated. These included the emergence of an intelligentsia, who wanted to modernise underdeveloped Hungary through investments in training and infrastructure. The main figures in this movement were Lajos Kossuth, a lawyer, and Count István Szechényi.

The reform movement was nationalistic in that the aim was to end the country’s subordinate position to and economic dependency on Austria. But it was simultaneously liberal, strove to achieve social reform and was influenced by foreign examples. It can most closely be compared with the corresponding movements in France, Italy and Germany in the mid-nineteenth century.

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 506

- Publication Year

- 2024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800792821

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800792838

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800792845

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781800792814

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18097

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (August)

- Keywords

- Second World War Hungary Holocaust Jewish resistance

- Published

- Oxford, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, New York, 2024. XVIII, 51 fig. b/w.