A Stab in the Ear

Poetics of Sound in Futurism and Dadaism

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of contents

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter One “Nebular, milky goblets full of pearls:” Futurism and the “musicality” of Young Poland

- 1. “Musicality” and sound in Young Poland poetry

- 2. Young Poland “musicality”: Continuations

- 3. Creative development of Young Poland sound aesthetic

- A. Young Poland semantics and modifications of its sound aesthetics

- B. Young Poland poetics of sound and moving beyond the symbolist aura

- C. Changes in orchestration, changes in meaning

- 4. Polemical stylization

- A. Changes in the poetics of sound, changes in semantics

- B. Young Poland orchestration, polemics in the area of semantics

- Chapter Two Imitating Khlebnikov? The neological current in Polish Futurism

- 1. Velimir Khlebnikov’s “gnosis of language”

- 2. “Secret speech”

- 3. Word formation and poetic encrustation

- 4. Futurist guessing games

- Chapter Three Freedom of sound or phono-semantic riddles? How much Dada is there in Polish Futurism?

- 1. The Dada controversy

- 2. A carnival of phonemes?

- 3. Dada-onomatopoeia?

- 4. Pure nonsense of Dadaist or native origin?

- 5. Ludic cabinets of curiosities or oneiric texts?

- 6. Ludic stories and images

- Chapter Four “plAY, mY shepherd’s pIPE:” Strategies of folklorization in Futurist poetry

- 1. Folklore phonostylistics

- 2. Futurist countryside lyricism

- 3. The realism pole

- 4. Stylization and poetic journalism

- 5. Humorous folklorization

- Conclusion

- 1. Futurist poetics of sound

- 2. Futurist heritage

- Bibliography

- Bibliographical note

- List of illustrations

- Index of names

- Index of terms

Introduction

Although Polish avant-garde poetry has been extensively researched and described, it turns out that certain areas have not yet been thoroughly explored in scholarly literature. This study presents findings in poetics and literary history, accounting for aspects that have not been scrutinized so far. The basic artistic context and main subject of analysis is the sound structure of poems written by Polish Futurists. Their works, both prose and poetry, are discussed from a comparative perspective, situating the outcome of the short-lived yet turbulent revolution against the backdrop of the European avant-garde and broader literary tradition.

The specific message of the Futurists, their “focus on being representative of their own paradigms, on their ‘Futurism,’ required.” Edward Balcerzan argues, “that they employ a special repertoire of hallmarks or emblems.”1 Certainly, using special sound devices, ones that capture attention yet challenge readers, is a distinguishing feature of their style. The most famous one-off issue published by the Polish Futurists was shockingly called Nuż w bżuhu [Knife in the belly], the publication blatantly violating conventional spelling and conventional taste.2 At that time, the sound structures of Futurist poems would indeed feel like a “nuż w uhu” [knife in the ear], while the unusual orthography and typography – like a “nuż w oku” [knife in the eye]. In many cases, these works can still have the same effect today.

The main focus of this monograph is not elaborate verse forms or complicated rhyme patterns3 but rather the various operations conducted at the word level.4 In the hands of Polish Futurists, individual words or their groups became a laboratory of sound and meaning. This cabinet of phono-semantic curiosities has long called for proper cataloguing and elaboration. This study concentrates predominantly on the field that can be called irregular sound instrumentation,5 sound instrumentation6 or phonostylistics,7 that is the use of certain devices based on sound repetition such as: alliteration, assonance, consonance,8 paronomasia, polyptoton, onomatopoeia, anaphora, epiphora, glossolalia or echolalia. Issues connected with versification are mentioned only in passing.9 Obviously, no study of phonic structures in Polish Futurist poetry could be truly complete without a detailed account of versification. However, it would be hardly possible to exhaust and categorize in a single book both the sonic regularities and irregularities of the poems in question. I believe, focusing on phonostylistics makes it possible to present ways in which Polish Futurists “stabbed” their audiences “in the ear.”

Let us begin with the fundamentals. First of all, it seems problematic to even define the general time frame of Polish Futurism. In the early stages of the movement’s development in Poland (1908–1918)10 the dominant role was played by press articles penned by writers other than the later Futurist poets. These texts would present selected theses formulated abroad. This study, however, primarily discusses actual poems. First attempts to write serious, innovative works of this kind date back only to 191911 when the first Futurist poetry books were published: Tram wpopszek ulicy [Tram across the street] by Jerzy Jankowski,12 Nagi człowiek w śródmieściu [Naked man downtown] by Anatol Stern13 and JA z jednej strony i JA z drugiej strony mego mopsożelaznego piecyka [ME from one side and ME from the other side of my pug iron stove] by Aleksander Wat.14 One needs to bear in mind, however, that the poetry volumes published since 1919 would also contain works written earlier, ones that are sometimes clearly distinguishable in terms of language and meaning from those already avant-garde in character.15 It thus remains difficult to decide how to address the non-Futurist poems included in volumes such as Czyżewski’s Zielone oko [Green eye] or Kreski i futureski [Strokes and futuresques] by Młodożeniec. There can be no certainty whether certain texts, even ones written in a more traditional style, were in fact composed before 1919 since only some works are dated, while original prints or manuscripts can be difficult to access. It is thus assumed here that the fact of publishing these works along with clearly avant-garde ones justifies including them in analyses here because these authors have themselves decided that these lyrics meet their own criteria of innovative poetry. Therefore, the year 1919 is considered here to mark the beginning of Polish Futurism as the “publishing date,” with subsequent analyses discussing works presented in books and journals since that year.16

It is even more difficult to establish the date when Futurism ended in Poland. Already in 1923 Bruno Jasieński argued in a text significantly titled “Futuryzm polski (bilans)” [Polish Futurism (an assessment)] that “Futurism is a form of collective consciousness that needs to be overcome.”17 The dusk of Futurism was also announced in the same year by Anatol Stern.18 Nevertheless, accepting this date as one marking the end of this movement would be scholarly unjustified. Although it does determine the end of Futurist group activities,19 this did not mean that individual writers stopped collaborating or ceased to write poetry that was still Futurist in spirit. Naturally, we should bear in mind that “since 1921, the achievements of the ‘first avant-garde’ were increasingly often brought under the banner of New Art.”20 This term was borrowed from the titles of two avant-garde journals: Nowa Sztuka [New Art] (1921/1922) and Almanach Nowej Sztuki F24 [Almanac of New Art F24] (1924–1925; the letter F, which denotes Futurism, was removed from the cover after publishing two issues).21 Nowa Sztuka published texts by Stern, Jasieński, Wat, Młodożeniec, Czyżewski, as well as ones by the leader and legislator of the Kraków avant-garde – Tadeusz Peiper. This study also takes into account this period, when younger writers became active, assuming after Zbigniew Jarosiński that the poets’ declarations regarding the end of Futurism were “rather premature.”22 Abstracting from texts written in the period when Nowa Sztuka was being published23 would be artificial and unjustified, all the more so since after 1923 “certain works that are important for the Polish avant-garde (or base on Futurist experiences) continued to be published.”24 These include: Ziemia na lewo [Earth to the left] by Jasieński and Stern (1924), Anielski cham [Angelic brute] by Stern (1924), Kwadraty [Squares] with the famous “Radioromans” by Młodożeniec (1925), Pastorałki [Dramatized Christmas carols] by Czyżewski (1925), and Słowo o Jakubie Szeli [The story of Jakub Szela] by Jasieński (1926).25 Zaworska and Jarosiński consider the year 1926 to mark the end of Polish Futurist poetry and Nowa Sztuka.26 The same date was also recognized by Henryk Markiewicz as indicating the conclusion of the first stage in the interwar period (until the May Coup): the phase of “initial, independence-driven optimism and gradual disillusionment accompanied by ideological radicalization in certain areas of literature.”27 This is an additional argument in favour of accepting this time frame for the purposes of this study (regaining independence considerably impacted the modality of literature written in this period).28 Thus, the years 1919 and 1926 are assumed to define the temporal scope of analysis in this study.29

To begin with, we should outline crucial questions in the area of literary history and theory. In 1959, Janusz Sławiński aptly notes:

Particular achievements of the Futurists could never be included in any system. Even if some of them permeated the literary tradition (which they certainly did!), they would immediately lose their history and genealogy. No one would remember where they came from because they were not elements of some poetics – it is only on this background – regardless of the movement’s fate – that they could retain their Futurist character.30

Polish Futurism was the sum of various talents; therefore, seeking any common denominators (especially in terms of poetics) within this heterogeneous formation may be risky. Vastly different creative methods were adopted by Jasieński, who was fascinated with Russian poetry, the Formist Czyżewski, or the avant-garde erudite Wat. Lyrical works by individual authors are discussed in monographs31 but any broader, analytical discussion of the movement’s output as a whole is a daunting task that was nevertheless undertaken by scholars focusing on the Polish interwar period, including Edward Balcerzan, Grzegorz Gazda, Andrzej Lam, Zbigniew Jarosiński, and Helena Zaworska.32 Still, questions of poetics constitute only one aspect of their multi-faceted studies.33 The reason for this is simple, in the case of Polish Futurism it would be difficult to offer a synthetic account like Sławiński’s Koncepcja języka poetyckiego awangardy krakowskiej because – unlike Peiper’s circle – Polish Futurism was highly heterogeneous and inconsistent, both in terms of declarations and artistic realizations.

Still, there is one area in which all writers discussed here proved to be highly talented and active, namely the development of the poem’s phonic tissue.34 All Futurists would foreground instrumentation devices, making them one of the foremost aesthetic aspects of their works. Certainly, even in this area we can indicate differences in attitude between particular authors. Although they all utilized similar instrumentation devices, they would be differently deployed in terms of frequency and function.35 Nevertheless, there are enough phonostylistic points of contact in the Futurist output to attempt a comprehensive analysis of sound instrumentation in their poems. The question arises, however, whether they can be regarded collectively as Futurist poetics of sound. Analyses conducted in this study are meant to help to provide an answer.

This book analyses poems by Wat, Stern, Jasieński, Czyżewski and Młodożeniec,36 but does not account for works by two other authors associated with Polish Futurism: Jerzy Jankowski and Adam Ważyk. Their output is not analysed in detail here and is only mentioned in passing, because from the perspective of literary history, they only partly overlap with Futurism, decidedly differing from Wat, Stern and Młodożeniec (whose works are not monolithic in their own right). The hybrid poetics of Jankowski bridges the avant-garde and Young Poland, and is often passéist.37 The subject matter of his poems is indeed Futurist in places (civilization, city, inventions), yet his means of expression are in most cases representative of the style characteristic for the turn of the centuries.38 On the other hand, poems by Ważyk, the youngest author from the circle of Futurism and New Art, exemplify his position at the crossroads between various influences and poetics. Independent and impossible to classify, his work cannot be reduced to any label, even a wide-ranging one.39 Works by these two artists – active at the two temporal and formal extremes of the Futurist movement – do not foreground the phonic dimension to the extent that is observable in poems by Futurists “proper,” actually offering little in the way of experimenting with sound. It may seem that this method involves marginalizing inconvenient texts that do not fit an a priori thesis. However, taking into account the specificity of works by these two poets it may be deemed that excluding their poems from analysis merely confirms known facts from literary history, namely that these flanking Futurists in fact worked outside the movement: either before or after it.

Another issue that is important for research presented here is the international situation of Polish Futurism. Poetic and programmatic texts by authors discussed here are characterized by diversity, freedom and arbitrariness, which reflects the lack of a homogenous artistic concept. The situation in Poland, specifically the “independence-driven optimism,”40 favoured those activities of young poets that were carnivalesque in spirit.

“The radical anti-traditionalism, whose rebellious slogans were repeated [by Polish Futurists] after Italians and Russians, acquired an additional meaning in the Polish context. Namely, it would entail breaking away from those patterns of literature that emerged during the period of national bondage.”41 Moreover, we should keep in mind that there was a certain temporal distance between the Polish movement and foreign avant-garde trends, along with their diverse inspirations and approximations. Poland found itself amidst strong influences coming from the West and the East, which certainly does not mean that the Polish reception of efforts made by Khlebnikov, Tzara or Marinetti was thoroughgoing. Still, writers in Poland would be aware of transformations occurring in literature and art abroad, as is confirmed by Anatol Stern’s poem “Reflektory” [Headlights], in which something quite typical of the avant-garde is manifested: the consciousness of a new tradition, “an international of new art:”42

było to wilno zima 1920

gdy w zielonej od skwaru równinie też rankiem

znad szarych skrzydeł się wychyliwszy ekranu

marinetti błyszczącą śmigę aeroplane

pieścił rękami jak nagą śmiejącą się z rozkoszy

szybko kręcącą biodrami kochankę

chodź chodź do mnie przyjacielu

i ty cocteau i ty majakowskij

boccioni tzara

i wy i oni

wszyscy

…

przez atlantyk podają sobie ręce nasze zgłoski!

galopują szybciej od australijskich koni!

…

rozpłaszczony trup chlebnikowa

długi o zapadłej piersi trup

i tylko

w gąszczy wśród kraśnych ptaków

pyszna sama dzwoni wciąż żywa głowa!

guillaumie pantero z pyskiem rannym

z obandażowaną lazurami głową

…

o guillaumie apollinaire

z jakich nadmorskich jeszcze sfer

dajesz mi płomień ust ramię brata

z jakiego morza z jakiego nieba z jakiego świata?

[it was in vilnius winter 1920

when in the scorching green plain also in the morning

leaning over the screen of grey wings

marinetti caressed the glistening propeller

with his hands as if it were a naked lover

laughing with joy and swinging her hips fast

come come to me my friend

you too cocteau and you mayakovsky

boccioni tzara

and you and them

all

…

our sounds extend hands over the atlantic!

galloping faster than australian horses

…

the spread-eagled body of khlebnikov

long corpse with sinking breasts

and only

in the thicket among garish birds

his haughty head rings still alive!

guillaume panther with wounded face

and head bandaged with azures

…

o guillaume apollinaire

from what spheres that are still seaside

are you giving me the flame of lips the brotherly arm

from what seas from what sky from what world?]

(Ant. 217–220; emphasis in the original)

The poem reveals numerous avant-garde contexts43 and seems to justify the thesis that the overall shape of Polish Futurism is a perfect example of assimilating influences and adopting various innovative trends. However, according to the Polish Futurist (misspelt) manifesto Mańifest w sprawie poezji futurystycznej, “Artysta, ktury nie twoży żeczy nowyh i ńebywałych, a pszeżuwa jedyńe to, co było pszed nim zrobione, po paręset razy – ńe jest artystą i powińen za używańe tego tytułu odpowiadać”44 [artists who do not create new and incredible things experience only the things that were done earlier for hundreds of times – they are not artists and should answer for using this title]. Consequently, it becomes necessary to specify several things from the perspective of literary history.

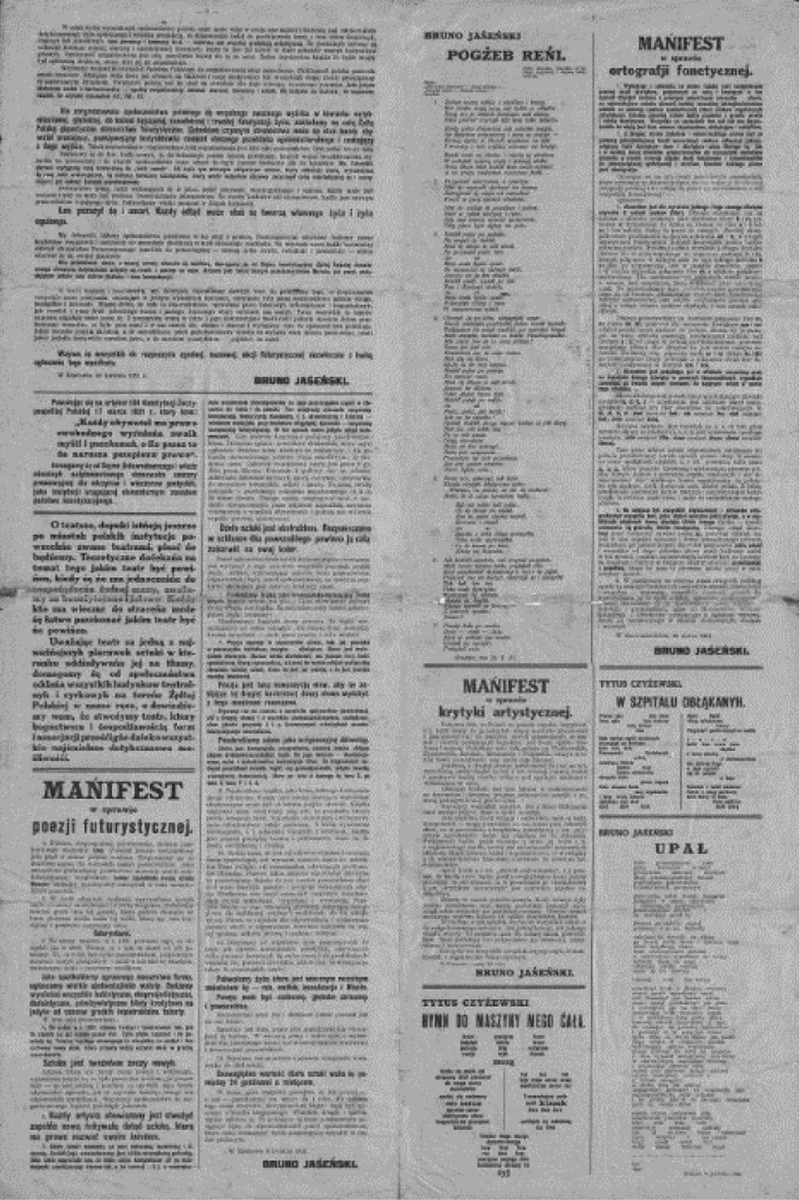

![Illustration 1.The first and the fourth (last) page of Jednodńuwka futurystuw [misspelt: One-off issue of the Futurists] published in Cracow in June 1921. Both content, spelling and format (320 x 940 mm) were shocking for the public.](https://cdn.openpublishing.com/images/preview-file?document_id=1319506&hash=21cbbd5d1122b96b4921a8aaaae6fffa&file=OEBPS/html/images/9783631895559_FM01_Ils_001.jpg)

Illustration 1.The first and the fourth (last) page of Jednodńuwka futurystuw [misspelt: One-off issue of the Futurists] published in Cracow in June 1921. Both content, spelling and format (320 x 940 mm) were shocking for the public.

Illustration 2.Double spread of Jednodńuwka futurystuw

Contrary to the belief that “the journey of Marinetti’s ideas from Italy to Poland was truly lightning-quick,”45 on the ground of artistic achievement we do not deal with an immediate artistic import, which means that the journey of ideas did not occur in the simplest possible way.46 News of the novel trend in literature and art (the early stage of Polish Futurism in the years 1909–1918)47 were in no way exhaustive.48 Polish critics would promote the model of an utilitarian avant-garde, presenting Italian Futurism as an optimistic, vitalistic, and activist movement that perfectly matched the situation of Poland after the First World War.49 However, the accuracy of information left a lot to be desired.50 Moreover, articles commenting on the achievements of the Italians scarcely discussed poetic texts. Critics would focus on discussing the movement’s ideas or reviewing exhibitions of works by Italian artists. Finally, before the First World War most of the would-be Polish Futurists were still in school.51 In effect, except for Czyżewski (who was one generation older52) they would know Italian Futurism only through “several slogans and a promising name.”53

Undoubtedly, poets discussed in this study could have known Russian works much better. A crucial role was played in this respect by their life histories. For example, in the years 1914–1918 Bruno Jasieński attended a middle school in Moscow, where he later took his maturity exam. To recall,

it was the city of two revolutions: one artistic and the other proletarian. … Scandalizing events organized by Futurists. Rebellion against all values … “Voskresheniye slova” [Resurrection of the word] by Victor Shklovsky (1914) and “Oblako v shtanakh” [Cloud in trousers] by Vladimir Mayakovsky (1916). … At that time, modernity was doubtless defined by zaum poetry, featuring texts composed from entirely new words created by poets from various roots … … And modernity would also transpire (can we blame the seventeen-year-old Bruno?) in the form of Severyanin’s wordplay involving beautiful, rare, often foreign words, especially of French origin.54

The same middle school in Moscow was attended by another Polish pupil: Stanisław Młodożeniec.55 Six years older than Jasieński, he “quickly discovered Yesenin, along with Khlebnikov, Kamensky and Kruchyonykh.”56 Aleksander Wat was also intimately familiar with Russian poetry, especially symbolist (incidentally, he attended a Russian school in Warsaw).57 Tytus Czyżewski, on the other hand, probably did not know Russian at all.58

Finally, we should address the Dadaist strand in Polish Futurism. It was probably more important for the young Polish poets to hear about the European Dada movement rather than to actually read works by Tzara, Ball or Schwitters, which were written almost in parallel to poems by Polish authors. The latter knew about Futurism spreading in Italy and were acquainted with Marinetti’s basic artistic assumptions already in the early stages of the movement, which means that these ideas circulated among very young poets (with the exception of the older Czyżewski) almost from the very beginning of their literary careers. The Dadaist movement, on the other hand, was younger. It developed almost at the same time as Polish Futurism. At that time there were still no biographical, personal ties between Czyżewski, Wat, Jasieński, Młodożeniec, Stern and the founders of Dada. There is “no specific information about reading the Dadaists.”59 Therefore, it was primarily the specific atmosphere of this movement that could impact Polish Futurism.60

As it transpires, knowledge about the activities of foreign poets-innovators was relatively scarce in Poland. Creating an avant-garde movement solely on the basis of hearsay and second-hand ideas seems rather arduous. The process was interestingly described ex post by the poets themselves:

When we started Futurism in Poland, we in fact knew no Futurist works. All it took was to make a single discovery contained in a three-word-long sentence: “words in freedom.” You need to see that this slogan, which claims that words can be freed, that they are like things with which you can do everything you want, was a tremendous revolution in literature. It was like, say, the revolution started by Nietzsche when he said that God was dead. … This has provided us with an incredible impulse. If it had not been for Marinetti, there would be no Joyce, not to mention Khlebnikov or Mayakovsky. Or alternatively, Joyce, Khlebnikov and Mayakovsky would have to create Marinettism. This is how it had to begin: from the claim that words are free. This is where the importance of Futurism is located, its weight and discovery, which played such a decisive role. In this sense, I would argue that the term Futurism is applicable in the context of this group, which had very moderate results (today people exaggerate these achievements in Poland) and played a marginal role at best.61

It is interesting to consider in this context the opinions of the Futurists on the genealogical conditions of their movement. Aleksander Wat notes:

In the years 1919–1924, Polish Futurism was a decade behind, even in relation to Russia, finding readymade foreign patterns, especially in Mayakovsky’s poetry of revolutionary gigantism and the Dadaist metaphysical anarchism.62

Certainly, the greatest influences were, on the one hand, Russian Futurism, i.e. Mayakovsky and especially Khlebnikov, and on the other – Dadaism. Thus, it would all boil down to Dadaism.63

According to Wat, Polish Futurism was therefore only a reflection or a mere shadow of foreign achievements. Although the fact of expressing this view long after the closing of the Futurist chapter in Polish literary history suggests, especially in the case of Wat, a significant shift in perception.64 Stern perceived this matter entirely differently. In his view, one can speak of simultaneous, intellectually independent co-occurrence of similar intellectual trends in different countries, since “certain innovating ideas emerge independently, as was often the case with the broadly understood Polish avant-garde (encompassing both Futurism and New Art poetry).”65 In this sense, Polish Futurism would be as original and important as the movements in Italy or Russia. Scholars specializing in the interwar period arrived at the following conclusions:

Beginning to work ten years after Marinetti and the great success achieved by the Cubists, as well as several years after Dadaism and Apollinaire’s “Zone,” Polish Futurists would draw on these experiences. They did not have to start from scratch and were aware of being part of the international front of New Art.66

What was Polish Futurism? It certainly was not a continuation of the movement that is assumed to have begun in 1909 with a manifesto published in Le Figaro and signed by Marinetti. Those efforts on the part of Italian artists were already a thing of the past. These events were separated from Polish developments by years of war, the regaining of independence, the October Revolution, the birth of Russian Futurism, and very importantly – the tempestuous Dadaist revolution. … When the young rebels from Warsaw and Kraków were entering the arena of artistic struggle, they had many things to choose from. Still, their choices were often inconsistent.67

Nevertheless, we should remember that choices were in fact limited and drawing on sources that were still unassimilated in Poland was difficult. Futurists would create their own original version of the avant-garde by utilizing relatively superficial inspirations from abroad. One can only try to guess which current in the European avant-garde had the greatest impact on Polish writers. Was it Marinetti’s idea of words in freedom? The concept (or rather concepts) of zaum? Dadaist disdain for all convention? It is impossible to ascertain, with pharmaceutical precision, the exact proportion of influences, inspirations and approximations.68 It seems unnecessary to discuss clear influences and interrelationships between specific poetic texts. What appears far more compelling is the question of construction. Accordingly, this study attempts to demonstrate which sound-related aspects of Polish texts are influenced by Dadaism, which appear to dovetail with the practices of the Italian leader of the Futurists, and which can be connected with the work of the Russian poet Velimir Khlebnikov.

* * *

Questions of sound instrumentation have been variously studied since centuries, both scientifically and para-scientifically, in an attempt to discover the semantics of individual phonemes as well as to unveil the mystery of beautiful and dissonant configurations of sounds.69 Certain sound structures have been ascribed magical functions, while others have been deemed (not without reason) as more expressive and strongly affecting the listeners. However, many theories that establish the meaning of specific speech sounds are utterly unverifiable, at the same time entirely contradicting the theory formulated by Ferdinand de Saussure.70 This study abstracts from such theories, which are often radically subjective, with the exception of ones that are connected with an avant-garde approach to poetry. Still, analyses contained here refer in places to scientifically verified claims about the effects of certain speech sounds.71 Considerations of the expressive character of individual sounds are nevertheless secondary to this study. It rather focuses on specific textual cases of developing clusters of sounds72 and functionalizing sound devices, situating them in the perspective of various interwar experiments and ideas about literary creativity.

Scholars have often raised the question of instrumentation in Polish Futurist poetry, but they would limit themselves to analyses of individual poems or terse statements made on the margin of broader discussions of works by specific authors, entire artistic movements, or even other avant-garde formations. What follows is a presentation of three critical accounts of Futurist handling of sound, which are important from the perspective of topics addressed in this study. These authors did not intend to develop a monographic approach to the question of sound instrumentation in Futurist poetry. However, their insights may help to choose the right method of approaching this body of works.

Grzegorz Gazda outlines a broad framework for examining the issues in question. He indicates that there were “two wings of [Polish] Futurist activities in poetic language,”73 originating in two kinds of inspirations:

The first one, which culminated in Khlebnikov’s practices and the concept of zaum, can be viewed as the tendency to seek the “internal form” of words, while the second is rooted in Marinetti’s idea of “words in freedom” and the Dadaist suicide of poetry.74

Thus, we may distinguish two groups of texts:

- 1. Poems close to the experimental word formation and “pseudo-etymologies”75 of Velimir Khlebnikov (which seems to constitute what Gazda calls “the tendency to seek the ‘internal form’ of words”)76 and reviving the context of various concepts of zaum.

- 2. Poems freely associating words, phonemes and morphemes, unrestrained by syntactic rules or any postulates to reveal truth and the depth of language.

Still, Gazda’s classification, which distinguishes two large categories of poems, does not exhaust the question of sound instrumentation in Polish Futurist poetry. He focused on experimental writing, taking into account strictly innovative, avant-garde practices. His approach disregards a relatively large group of pieces whose sound structure is not shaped in an avant-garde manner and remains closer to the poetics of Young Poland or patterns drawn from folk literature. In order to display the entirety of sound instrumentation devices in Polish Futurism, Gazda’s typology should be supplemented with more traditional, or even passéist tendencies. A broader account of the Futurist approach to sound additionally necessitates, on the one hand, a detailed consideration of the presumed Dadaism of some works by Polish poets, and affinity with ideas developed by Marinetti on the other.77 It also becomes paramount to explore the connection with the Russian idea of zaum.

Analysis of instrumentation elements in Futurist poetry (on the basis of specific examples) and their functions also constitutes an important component of observations made in this area by Edward Balcerzan.78 He describes, among other things, a series of poetic works identified on the basis of the way in which they introduce and functionalize sound devices. This series comprises two stylistic sequences, which share the point of departure: the poem “Na rzece” [On a river] by Jasieński. Balcerzan discusses not the sound structure of all Polish Futurist poems. However, we should reconstruct his line of argumentation regarding the classification of a certain group of poems which are strongly marked by instrumentation.

Balcerzan ascertains a fact that is fundamental to this study. Namely, he demonstrates that the sound dimension cannot be regarded merely as a Futurist phonetic game, or an isolated configuration motivated solely by euphony, because in many cases it strongly correlates with semantics. This would be confirmed by an experiment that Balcerzan conducts as part of his analysis of the poem79 in which “the meanings of individual words seem to be, at first glance, subjected to instrumentation to such an extent that they appear to be insignificant, or at least neutral:”80

Details

- Pages

- 536

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631899199

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631899205

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631895559

- DOI

- 10.3726/b20741

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2023 (July)

- Keywords

- Figures of sound in the Polish avant-garde European literary practices Polish literary tradition

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2023. 536 pp., 14 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG