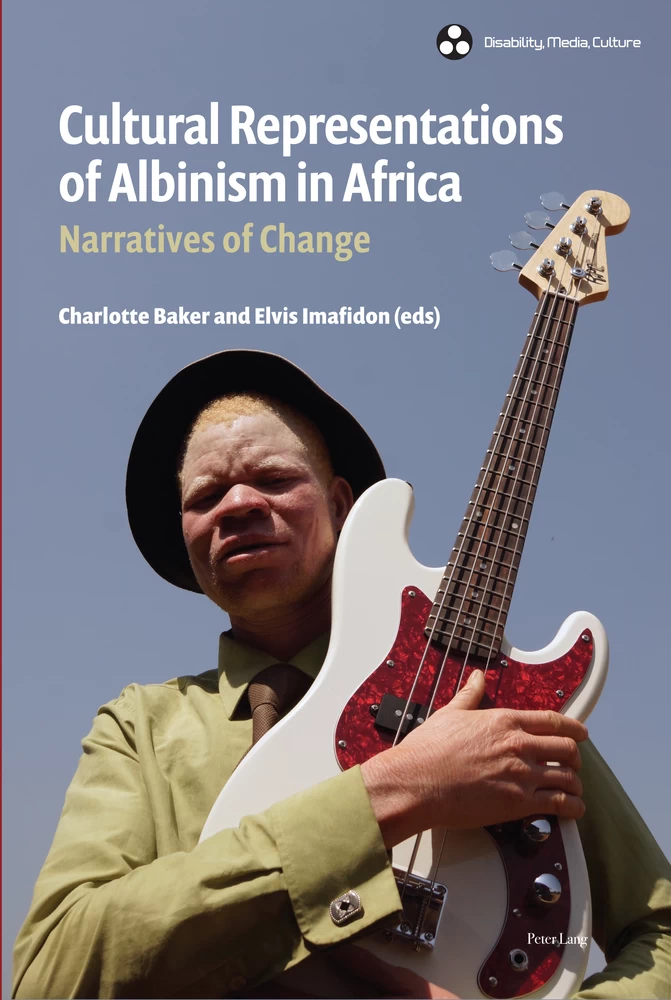

Cultural Representations of Albinism in Africa

Narratives of Change

Summary

(Carli Coetzee, Editor, Journal of African Cultural Studies)

«Highly intriguing and skillfully nuanced, this book evaluates several methods of advocacy on behalf of people with albinism from Africa, who often face stigma and physical attacks. The result is a rich commentary on what has worked, what didn’t and why. This is recommended reading for anyone engaging in advocacy for any marginalized group in parts of Africa and elsewhere.»

(Ikponwosa Ero, Former UN Independent Expert on the enjoyment of human rights by persons with albinism)

The challenges currently faced by people with albinism in many African countries are increasingly becoming a focus of African writers, storytellers, artists and filmmakers across the continent. At the same time, a growing number of advocates and activists are taking account of the power of cultural representation and turning to the arts to convey important messages about albinism – and disability more broadly – to audiences locally and internationally. This volume focuses on the power of cultural representations of albinism, taking into account their real-world effects and implications. Contributions from academics and albinism advocates range across traditional beliefs, literature, radio, newsprint, the media, film and the arts for public engagement, contending that all forms of representation have an important role to play in building sensitivity to the issues related to albinism amongst national and international audiences. Contributors draw attention to the implications of different forms of cultural representation, the potential of these different forms to open up new discursive spaces for the expression of identities and the articulation or critique of particularly difficult issues, and their potential to evoke far-reaching social change.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword. Unweaving Harmful Fictions: Cultural Representations of Albinism in Africa (Thando Hopa)

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Changing Narratives of Albinism in Africa (Charlotte Baker and Elvis Imafidon)

- 1 Challenging Traditional Understandings: Embedding Accurate Knowledge of Albinism in African Cultures (Elvis Imafidon)

- 2 Literature as Advocacy: Fictional Representations of Albinism in African Contexts (Charlotte Baker)

- 3 Debunking Stereotypes or Reinforcing Them? The Representation of Albinism in Three Nigerian Films (Kolawole Olaiya)

- 4 Albinism between Stigma and Charisma: Varying Interpretations of Two Photographs from South Africa (Christopher J. Hohl)

- 5 Sparks of Otherness: Producing Representations of Albinism in Documentary Films from the Global North (Giorgio Brocco)

- 6 Voices that Stand: The Power of Film for Advocacy on Albinism in Africa (Sam Clarke)

- 7 Theatre and Stigma Reduction: Can Theatre Raise Awareness on Albinism? (Tjitske de Groot, Pieter Meurs, Mustapha Almasi, Ruth Peters and Wolfgang Jacquet)

- 8 Building Community Understanding of the Genetic Explanation of Albinism through Interactive Performance Art in Tanzania (CHRISTIANE NDEDI ESSOMBE, Jon Beale and Patricia Lund)

- 9 ‘We gon be Alright’: The Musical Response to the Killing of People with Albinism in Malawi (Ken Junior Lipenga)

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Series Index

Figures

Figure 4.4. Polynation album cover, The Electric Petals / Teal Records (1995).

Figure 8.1. Project theory of change diagram.

Figure 8.2. Drawing depicting the opening ‘fight’ scene T. R. Mnyavanu.

Figure 8.3. Drawing depicting the Reproductive Dance by T. R. Mnyavanu.

Foreword

Unweaving Harmful Fictions: Cultural Representations of Albinism in Africa

Albinism in general has had many harmful fictions woven onto its body. The fictions arise in the form of biological and spiritual myths, as the collective imagination in any given society dictates – who is normal and who is abnormal, what is natural and what is supernatural, who is Black and who is White, who is human and who is other? Skin colour propels the body of albinism into an array of socio-political consequences, each of them setting artificial hierarchies on who fulfils the standard of what it is considered to be human. All of these consequences are usually a question of power and are moulded through the storytelling mediums of culture.

If we look more closely into the sub-Saharan African context, there are many social constructs that are not preserved through the written word, but are secured within the tenets of the culture. The dictates of whose humanity is subjected to cultural devaluation moves from one network of beliefs to the next, across nations, landing impactfully on the body it is targeted towards.

Albinism is a personal subject for me, as a Black African woman with albinism. I have worked in the business of representation through media, moving into the wilderness where many narratives compete to confine albinism to a marginalized social position. The narratives that we disseminate into culture become a form of negotiation, resistance and intervention in pursuit of social justice, inclusion and equity.

The body of analysis compiled in this book makes the reader appreciate how we can decentralize the portrayal of a particular human existence, in this case, Black African albinism, through cultural mediums such ←xi | xii→as theatre, literature, photography, film, music, interactive performance as well as figureheads who are custodians of culture. There is a deep and well-considered exploration and critique of the different knowledge systems and storytelling mediums that explore the ability to reinterpret the body of Black African albinism out of the metaphysical realm and back into its personhood.

Seasoned scholars and activists have laboured over their thoughts, experiences and insights to share a multi-layered set of perspectives that lean on several strands of cultural representation. Charlotte Baker and Ken Junior Lipenga explore whether literature or music serve as conscience-keepers that intercede on behalf of the body of albinism. We journey through efforts that aim to invoke empathy, protest, perspective taking or accountability with the objective of abnormalizing violence, exclusion and/or discrimination as a social norm in the experience of albinism in Africa. Christopher J. Hohl, through incisive analysis of photographic anecdotes, delves into salient nuances and contexts that create conditions of duality and tension in interpreting or even reinterpreting a highly racialized body. These parameters extend to the world of moving pictures, where Giorgio Brocco and Sam Clarke explore the ethics of responsible storytelling in film, more so when there are layers of racial discrimination that have the potential to bruise the image and experience of the body even further. As I harmonize the perspectives formed within the avenues of film, Kolawole Olaiya enriches this lens by unpacking the varying social constructs that impact the body of albinism and how, in one context, storytellers offer differing portraits of representational outputs.

Once we migrate out of film and into a reality that we can touch, one would do well to remember the timeless ability inherent in the theatrical world to assemble people, performance and information distribution as effective means to alter social misconceptions. Contributions to this collection from Tjitske de Groot et al., and Christiane Essombe, Jon Beale and Patricia Lund re-emphasize the notion of theatre as an accessible medium, subtly introducing the understanding that harmful narratives will continue to persist if constructive narratives are restricted and not broadcast through accessible mediums. This builds on Elvis Imafidon’s insight into how to use culturally relevant means to negotiate a more accurate comprehension of ←xii | xiii→the body of albinism. This analysis is deeply rooted in observing cultural compositions and knowledge systems, within African societies, that form knowledge bearing and knowledge sharing approaches that become fundamental when conscientizing a collective consciousness.

The book surveys several pillars of representation as instruments of cultural production. It also edges into a reflection of a time that recognizes how much needs to be rethought from the cultures that we have inherited. The body of Black African albinism is in a constant war with the conventions that have imposed allowable transgression onto its humanity. We cannot only emphasize the power of storytelling, we must also equally amplify the responsibility of storytellers.

This compilation of work – in its entirety – is hauntingly thoughtful. It carries the load and complexity of stories that are reflected in many lives embodied within this body politic, but simultaneously, it holds the kind of critique and analysis that makes one conceive of all the elements of a turning tide.

Read the library of insights contained in this book critically, with an open mind, and make a commitment to understanding a reality that is acutely unique in some respects and significantly common in others. Collect the perspectives and strategies you find useful and valuable. Whichever path this book directs you to, I hope that you will not only be fuller in knowledge, but that you will also be more intentional in crafting inclusive, equitable, responsible and human-inspired representational work for groups which have had marginalization imposed on them by a culture that is only beginning to learn how to mend itself.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank everyone involved in the development and publication of Cultural Representations of Albinism: Narratives of Change, including the contributors, the reviewers and all those who encouraged us along the way.

We are particularly grateful to Thando Hopa for generously agreeing to write the Foreword to the book. We would also like to thank Laurel Plapp, Senior Acquisitions Editor at Peter Lang, for her advice throughout the development of the volume and Carli Coetzee for her early input.

This collection of chapters has partly emerged from the ‘Alternative Explanations: Disability and Inclusion Africa’ project, which is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Global Challenges Research Fund and led by Charlotte Baker and Elvis Imafidon in collaboration with Kobus Moolman (University of the Western Cape, South Africa), Nandera Ernest Mhando (University of Dar es Salam, Tanzania) and Emelda Ngufor Samba (Université de Yaoundé, Cameroon).

Special thanks are due to the Department of Languages and Cultures at Lancaster University for the financial support of this publication.

Introduction

Changing Narratives of Albinism in Africa

Oculocutaneous albinism is a recessive genetic condition which is characterized by a reduction or lack of pigmentation in the hair, skin and eyes of people with albinism. This results not only in visual impairment and the vulnerability of skin to sun damage and skin cancer, but can also lead to the stigmatization and social marginalization of people with albinism because of their visible difference, particularly in sub-Saharan African contexts.1 There is some debate about whether or not people with albinism are disabled. The Kenyan politician and disability advocate Isaac Mwaura asserts that people with albinism are ‘black people with a white skin, who are disabled, but not disabled enough’.2 Indeed, defining albinism as a disability has not always been a straightforward matter. In medical terms, while the skin of people with albinism is vulnerable to sun damage, which can lead to skin cancer, measures can be taken to reduce this risk, such as limiting exposure to the sun, applying sun cream and wearing a wide-brimmed hat and long-sleeved clothing. ←1 | 2→Equally, although people with albinism are visually impaired, their vision can be improved with vision devices and alterations to lighting and seating position.3 However, a lack of access to accurate information on albinism and limited access to sun creams and vision devices disables people with albinism, as do the beliefs attached to albinism. Using the social model of disability, which identifies disadvantage that stems from a lack of accommodation of a body in its social environment, it becomes clear that people with albinism are indeed disabled. Sam Clarke and Jon Beale go a step further, to suggest an expanded definition of disability that includes ‘socially originating barriers to civil participation’ as a way of incorporating albinism.4

The beliefs and stereotypes attached to albinism are one of the greatest impediments to a person with this condition taking full part in society. These beliefs range from misconceptions and stereotypes to traditional and contemporary myths, and sit alongside varying levels of understanding and acceptance of biomedical explanations for albinism.5 At the most extreme, these beliefs are manipulated for economic gain, resulting in the attacks on people with albinism for their body parts mentioned above. However, despite the focus in the media, advocacy and scholarship on the threat that this trade in body parts poses to people with albinism, a far bigger danger is exposure to solar ultra-violet radiation, which results in sun damage and a significant increase in the risk of skin cancer in people with albinism. As Sian Hartshorne and Prashiela Manga remark, oculocutaneous albinism causes a reduction in, or lack of production of the pigment melanin, which makes the skin more susceptible to sun damage and increases the risk of skin cancers.6

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 246

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800791404

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800791411

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800791428

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781800791398

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17858

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (December)

- Keywords

- Albinism Africa Representation Charlotte Baker Elvis Imafidon Cultural Representations of Albinism in Africa

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2022. XVI, 246 pp., 5 fig. col., 2 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG