Participation & Identity

Empirical Investigations of States and Dynamics

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Constructing Local Identities in Multiparty Interactions with Tablets (Heike Baldauf-Quilliatre & Biagio Ursi)

- Participation and Identity Construction in the Context of Genre and Format Patterns: The Case of 8 out of 10 Cats Does Countdown (Alexander Brock)

- ‘Nice try, loser’: Participation and Embedded Frames of Interaction in Online Sports Commentaries (Jan Chovanec)

- Politicians’ Identity on Twitter: ‘Doing Roles’ in Mediatised Political Online-Communication (Sascha Michel)

- Participation and Identity in Sex Education (Janet Russell)

- When the Algorithm Sets the Stage: Participation, Identity and the 2020 US Presidential Election on Instagram (Peter Schildhauer)

- Indexing Multilingual Identities in Urban Namibia: The Linguistic Landscapes of Windhoek and Swakopmund (Anne Schröder & Marion Schulte)

- Mods, Alts & Bots – Participation Roles and Identity Construction on Reddit (Merle Willenberg)

- Series Index

Constructing Local Identities in Multiparty Interactions with Tablets

Abstract: This chapter deals with family gaming interaction on a large tablet in the presence of a library staff member who is in charge of organising and mediating the whole encounter. We investigate the participation framework with regard to the mediator’s role: How is this role collaboratively constructed and achieved in interaction? How do practices of participation contribute to this identity-in-talk construction? And how is this participation work organised with regard to the tablet? We show three different embodied participation practices which characterise the library staff member’s identity as mediator: He organises the interaction, explains the games and disengages from the family gaming interaction.

Our study explains how a particular identity-in-interaction practice is co-constructed by all participants through specific participation frameworks. It specifically highlights the particularity of screen-centred interactions and the place of the screen within the participation framework. It therefore aims to contribute to a better understanding of screen-centred interactions vis-à-vis participation and identity construction.

Introduction

Multiparty interactions are very frequent in different situations of our lives. At different times they include different kinds of material objects that play a pivotal role in participants’ exchanges: museum guides explaining artworks in a museum, pupils and teachers orienting to a blackboard, team members sharing a screen during an online meeting, etc. In all these interactions, the object plays an important role in the construction of the participation framework. As Lerner (1996) puts it: “I consider this [i.e. the relationship of a participant to a material object] a social relationship […] since […] it is the object’s social position in a recognisable course of action that seems to be relevant here” (1996: 287). Participants, then, orient not only to their co-participants but also to the object; sequences become meaningful with respect to the object (i.e. object-centred sequences; Tuncer et al. 2019). Simultaneously, participants take up an “embodied stance toward the objects” (Rae 2001: 271). They position themselves as well as the others with regard to it and, for instance, display categorisations by taking different stances into account.←11 | 12→

Goodwin (2007) argues that through participation frameworks “parties shape each other as moral, social and cognitive actors” (2007: 71). In other words, participation frameworks are closely related to different types of stances. We therefore consider participation closely related to identity as “identity-in-talk” (Antaki & Widdicombe 1998; Benwell & Stokoe 2006; Deppermann 2013) and investigate identity construction through practices of participation. Revisiting the Goffmanian concept of “footing” (Goffman 1981), Goodwin & Goodwin (2004) draw on participation as a practice that highlights the “reflexive orientation” (2004: 240) between all participants, not distinguishing a speaker- and a hearer-side. In object-centred sequences, “[t]he joint consideration and handling of objects creates opportunities for achieving intersubjectivity locally and in a dynamic way” (Tuncer et al. 2019: 390). This implies moral identities and complex relationships vis-à-vis the participants and the material object.

In this chapter, we propose to bring together identity-in-talk, participation frameworks and object-centred interaction by investigating a particular type of multiparty interaction where at least three participants interact on a large tablet propped against a wall. The “object”, in that case, is rather complex: It constitutes both a tactile surface and a system of signification, and participants can relate to each of these aspects. One of the participants is a staff member of a public library; the other participants are mostly members of one family. The interaction takes place in a public space. We are specifically interested in the practices employed to construct an identity as mediator through the interaction and we want to highlight (1) the interactive character of this identity construction and (2) its embodiment.

Our analytical focus is thus on the staff member and, especially, on a multi-layered characterisation of his role. In contrast to other conversational research on mediators (e.g. Pekarek Doehler 2002; Stokoe 2013; Ticca & Traverso 2015), he does not mediate between different parties, but encourages a family gaming interaction on a screen. In our data, he often acts as the “one who knows”, as a third-party outside the teams of players. In other moments, he participates and is actively involved in the gaming. In both cases, there is no a priori positioning, but the positioning emerges as collaboratively accomplished and accounted for all participants.

Interaction with (Digital) Objects

With an increasing interest in the embodiment of interaction (e.g. Mondada 2019; Nevile 2015), several studies have particularly focused on material objects and how they are handled, manipulated, or shown in interaction (e.g. ←12 | 13→Nevile et al. 2014). The increasingly common use of digital objects as “situated resource” (Nevile et al. 2014: 14) goes along with a growing number of (conversation analytic) studies interested in the particularities of interactions involving or based on digital objects. Besides research on mediated interactions and mediated practices (e.g. Arminen et al. 2016), we want to point out studies analysing the use of smartphones (e.g. Brown et al. 2013; DiDomenico et al. 2018; Höflich & Kircher 2010; Licoppe 2013; Oloff 2019; Porcheron et al. 2016), or, less frequently, studying tablets in interaction. While smartphones or mobile phones are generally considered in various interactional settings and environments, studies of interactions with tablets mostly concern the context of classroom interaction (e.g. Jakonen & Niemi 2020; Rusk 2019) or deal with tabletops and similar technological devices in museums (Hornecker & Ciolfi 2019; vom Lehn et al. 2007; Rothe 2017). Nevertheless, tablets can be used as interactional resources in different types of interactions, and in several cases there are substantial differences compared to smartphones. This concerns, for instance, the case of large tablets, which can be used by several participants simultaneously.

Drawing on our data, we are particularly interested in object-focused interactions that started to receive considerable attention mainly with the emergence of workplace studies and the analysis of settings with technological devices. In object-focused interactions, talk, embodied conduct and object-oriented actions are closely related (Tuncer et al. 2019: 387). Physically available objects are made relevant in interaction “so that participants collaboratively create a shared material environment and establish a relationship through these objects” (Tuncer et al. 2019: 387). More generally, Tuncer et al. (2019) describe, with regard to object-focused interactions, object-centred sequences as “recognisable sequences on their own” (2019: 387). We would like to highlight particularly the fact “that they make talk-in-interaction topically and sequentially contingent on participants’ joint orientation to the object” (2019: 388). This impacts largely on the practices of participation as well as the positioning of the interactants.

Concerning digital objects more specifically, Raclaw et al. (2016), who draw for instance on “mobile-supported sharing activities” (2016: 363), describe the mobile phone as “a focal point for joint participation during face-to-face interaction” (ibid.). In a similar way, the screen-based interaction on the tablet in our data can be considered the central element that not only induces co-participation but also makes different practices of participation relevant, according to the spatial, relational and epistemic configurations. When participants position themselves and others with regard to these configurations, they necessarily take into account the tablet as a particular digital object (in other words: as a tactile surface and as semiotic system(s)).

←13 | 14→Simultaneously, Tuncer et al. (2019: 390) describe emerging membership categories as ‘object-sequence-generated’: “These categorial devices and incumbencies enacting rights and obligations are category-bound to the object, and might be consequential to the way an object-centred sequence unfolds”. Licoppe & Tuncer (2019) show, for instance, how showing sequences in video-mediated interactions display membership categorisations. In our data, categories such as the “mediator” are closely related to epistemic stances towards the tablet and its place in the spatial configuration. But these categories need to be made relevant and established by all participants in the respective talk-in-interaction.

Data and Methodology

Our analysis is based on video recordings of interactions with a large tablet during a children’s festival. It is part of a larger project on inter-generational interactions including technical devices. This project has been conducted by researchers in linguistics, information sciences and education in cooperation with the Lyon City Library.

The data were collected in 2016: During the annual children’s festival “Le Printemps des Petits Lecteurs” (Small Readers’ Spring), the library offered different activities especially to families. Among them, (grand)parents and children could register to play different games together on a large tablet propped against a wall. A library staff member led the gaming session that took place in a large room, simultaneously with other activities (e.g. freely accessible board games).

The tablet was about 70 centimeters high and one meter wide. At least the adults had to sit or kneel to be able to play. A pad approximately as large as the tablet was placed in front of it.

The activity was intended for one family at a time, but sometimes two pairs (parent and child) who knew each other registered together for the same time-slot. Each slot was supposed to last around 10 minutes. Based on the willingness of the family and especially of the children, our recordings last from 7 to 24 minutes. Altogether, we recorded 10 groups composed of at least one child, one family member and one library staff member. The recordings were conducted with five cameras and five different scopes: two lateral scopes to register gestures and gazes of all participants, one camera fixed on the upper part of the screen for a frontal recording of the participants, one camera behind the participants and in front of the screen to give access to the whole screen and one mobile camera handled by a researcher. All video signals were edited and finally combined in a multiscope video, allowing access to all views simultaneously.

←14 | 15→Our analyses were conducted within the framework of ethnomethodology and multimodal conversation analysis, based on the claim that social categorisations and linguistic structures are not predetermined but co-constructed and developed in talk-in-interaction by the participants themselves through different social actions. For example, only by acting as X do they identify as X. Regarding our data, this means that the library staff member becomes the mediator in this interaction because he1 acts as mediator. Since its early beginnings, conversation analysis (CA) and especially membership categorisation analysis have shown that social actions as well as identities – even the unmarked, ordinary ones – are always co-constructed by all participants (Sacks 1984, but also Deppermann 2013; Greco & Mondada 2014; Stokoe 2012). Thus, doing being a mediator is not limited to one participant’s actions, but to the sequential structure of interaction. Interaction itself is hereby not reduced to verbal exchanges but regarded as multimodal and embodied: Gazes, body movements, gestures, facial expressions and the manipulation of objects allow for the construction of interaction spaces or the simultaneous involvement in different participation frameworks; besides, actions can be accomplished partially or fully without verbal resources. This aspect becomes particularly important for the analysis of non-verbal activities such as playing on tablets in multiparty-interaction.

Doing Being a Mediator

Concerning official instructions, the role of the library staff member is rather indefinite: He has to supervise and guide the interaction on the tablet. The library did not give any more precise instructions concerning the role of the staff member within these screen-based multimodal interactions. We were therefore interested in the way they understood and constructed their position in this rather complex encounter. A preliminary look at the data revealed a general posture as mediator. Firstly, the staff member acts as technology mediator between the users and the tablet: He explains game rules, guides action sequences, suggests strategies, solves technical problems, etc. Secondly, he acts as a mediator in a multiparty-interaction where the participants’ main focus is on a tablet.

In the following, we will show how the staff member is positioned as a mediator. With respect to the three main activity types discussed below, we will highlight different embodied practices which categorise the staff member as the one ←15 | 16→who organises the interaction, who explains the game and who is not primarily involved in the gaming activity.

Organising the Interaction

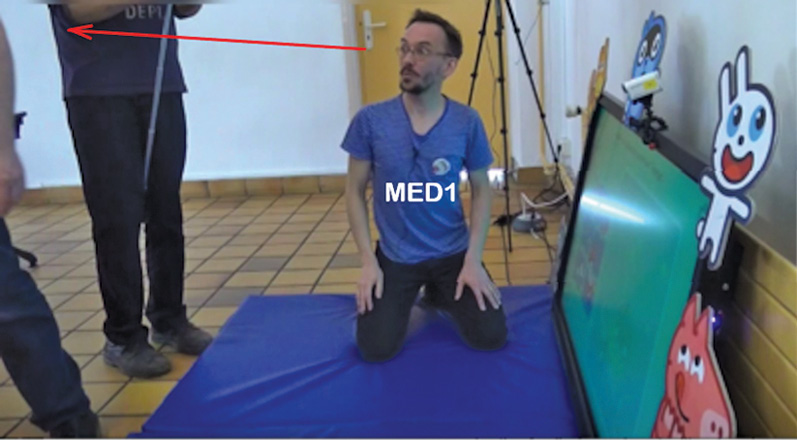

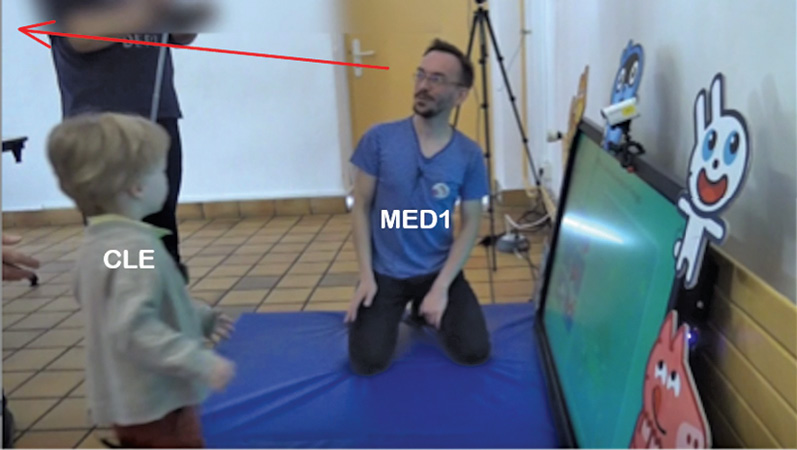

From the beginning of the encounter, the staff member positions himself as organiser: He always opens and mostly closes the interaction, provides technical help and initiates the game or game changes. Generally, at the beginning of the interaction, he is already kneeling on the left side of the tablet, ready to welcome the family (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1:G2 0:00

Figure 2:G3 0:00

The following extract shows the opening of an interaction between the staff member MED1 and a family of two, a grandmother (GM) and her grandson (CLE, Clément). Extract 01 starts after the first 47 seconds of the recording. The staff member has just chosen a game on the screen according to the presumed age of the child and is talking with the technical staff. He keeps his initial position alongside the tablet. Once the technician has given her approval, the family approaches the pad (outside the scope of the camera). MED1 switches his gaze and his head from his standing colleague first to the grandmother, and then to the approaching child, opening the interaction by greeting GM and CLE. He then initiates a pre-sequence (Schegloff 2007), introducing the explanation of the game.

|

Extract 01: Group 22 | ||

|

01 |

GM |

y a c’est là c’est là clément= |

|

there’s it’s here it it’s here clément | ||

|

02 |

MED1 |

=non mais il a joué au ballon #3 |

|

no well he played ball | ||

Figure 3

|

03 |

(.)#4 |

Figure 4

|

04 |

MED2 |

ouais |

|

yeah | ||

|

05 |

(0.6)+(0.1) | |

|

med1 |

+...> | |

|

06 |

MED1 |

bon+jou:#5[:r] + |

|

good morning | ||

|

med1 |

..>+looks at GM+ |

Figure 5

|

07 |

GM |

[bon]jour* |

|

good morning | ||

|

med1 |

*leans towards CLE-> | |

|

08 |

(0.1)+(0.2)#6 | |

|

med1 |

Details

- Pages

- 232

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631883303

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631883310

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631829745

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19939

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (November)

- Keywords

- Text and media linguistics Social media discourse Media studies

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2022. 232 pp., 47 fig. col., 53 fig. b/w, 1 table.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG