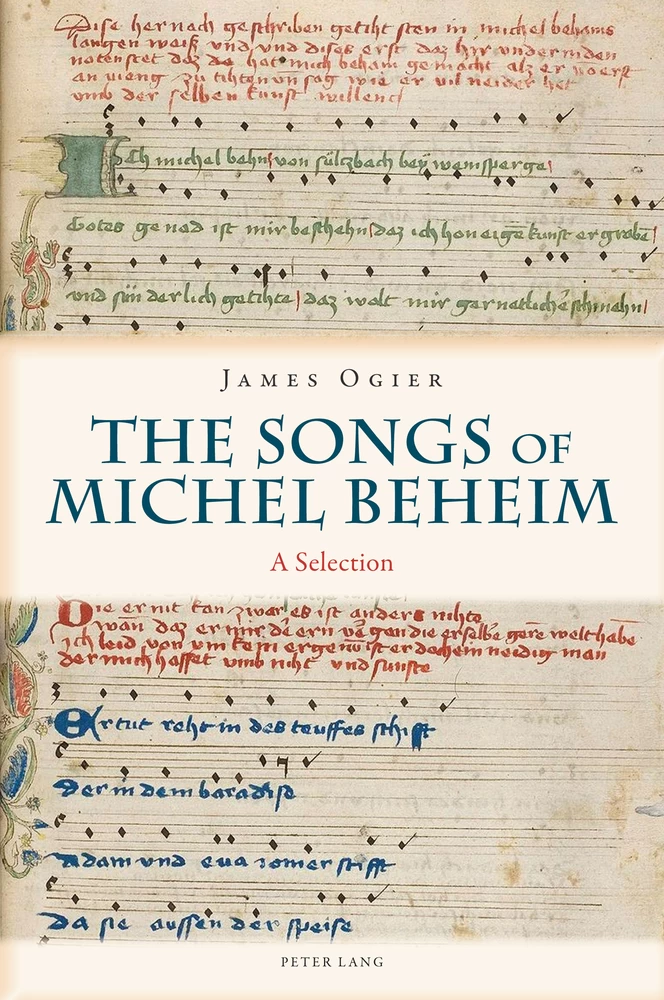

The Songs of Michel Beheim

A Selection

Summary

«Our foremost translator and commentator, Professor Ogier is a surefooted guide to the challenging oeuvre of Michel Beheim, an under-appreciated author of vast range. Ogier’s colloquial, yet true renditions perfectly capture the tone and timbre of a long-stilled, but vital voice. This volume is particularly welcome because it contains many of the first English versions of richly diverse and important song-poems. It is to be hoped that this volume finds a place in our university classrooms, where Michel Beheim will surely gain an appreciative audience.»

(Professor William C. McDonald, University of Virginia)

«James Ogier meets the scientific standards required since the new assessment of Beheim’s poetry in the history of pre-Meistersang. This concerns the selection of the poems with its special focus as well as the transcription of Beheim’s melodies as an integral part of his art. Therefore, I strongly endorse this publication.»

(Professor Sieglinde Hartmann, Universität Würzburg)

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Songs

- Zugweise

- 22 On young Duke Albert of Bavaria

- 23 On the dignity of song and that it is now defamed

- 24 On Michel Beheim’s birth and his arrival in this land

- 26 A parable about the flatterers and layabouts of whom one finds many at court

- 27 About a loose woman

- Kurze Weise

- 54 A fable that I composed when the princes allied themselves with the imperial cities

- 55 On the timorousness of the city folk and the boldness of the nobles

- 62 How I first got the urge to make poetry, and how I found my first patron

- Osterweise

- 90 A fable about the lords of Austria

- 96 About the University of Vienna

- 98 On the awful conditions among the nobles

- 99 About a despot named Voivode Dracula of Wallachia

- 101 About the Turks: A message received in Nuremberg

- 102 On those who claim the songs of the old masters as their own

- 104 This poem tells about King Ladislas, the King of Hungary, and how he battled the Turks (the Battle of Varna November 10, 1444)

- 105 About the battle of Körmend

- 106 About Count Jiskra

- 112 About the Viennese

- 113 On Bohemia

- Verkehrte Weise

- 190 On many kinds of licentiousness. First, sins against nature

- 191 On licentiousness between relatives and kin

- 192 On adultery

- 193 On the unchastity of maidens

- 235 This poem tells of many types of heretics and sorcerers

- 237 This song tells about the Turks and berates the princes for doing nothing about them

- 238 This is about the Turks and rebukes all the nobility for doing nothing

- 239 Another one about the Turks and it scolds the lords of Austria for their disunity

- 243 A fable about the lords of Austria

- 244 A parable about Duke Albert

- Hofweise

- 300 The following songs are in Michel Beheim’s Hofweise, and the first one is a parable on the Holy Trinity and it begins with these notes

- 301 On the course of the heavens and the stars

- 309a This is an allegory that I composed for my lord, King Ladislaus in Prague in Bohemia and tells of the heretics. Since I dared not sing publicly before them, I composed it as a parable, and they had to listen to it anyway.

- 309b When I had sung this song to the king, he told me I should explain its meaning. So I said: “If your Grace tells me what you would think of those who were so disobedient, I will interpret it.” Then he said he would be unmerciful to them. Then I sang the interpretation thus.

- 310 A lampoon on the heretics in Bohemia; I also composed this in Prague, but secretly

- 311 This is a fable about my lord King Ladislaus’s officials, but not about the pious ones, but rather about the evil and disloyal ones

- 314 A fable about a monkey

- 316 A fable about a crab, directed at the clerics

- 318 A fable about an ass and a lion pelt

- 319 A fable about birds and animals against uncouth people

- 323 On the scorn I endured in Heidelberg about my singing

- 324 What happened to me in Altenburg (Mosomagyaróvár) in Hungary

- 327 On my Sea Voyage

- 328 Here I have composed a song about the Turkish Emperor Mehmed, about how he conquered Constantinople and laid waste to Serbia, and what great shame and damage he suffered at the Byzantine city of Belgrade, and about the crusade the Christians thereafter led against the Turks, and how the noble lord Count Ulrich of Celje was murdered. All this you will hear, as I, Michael Beheim, participated in the voyage. (The siege of Belgrade)

- 329 About my six greatest perils

- 352 On the governing of the world and the course of the stars

- 354 A Pig-Out

- 356 This is about my lord, King Ladislaus, and about the loyalty of the Bohemians and the disloyalty of the Hungarians

- 357 This is about the origin of the Teinitz family

- Slegweise

- 358 These songs written here are in Michel Beheim’s Slegweise or -melody and the first one below in these notes tells of the vexation that he had when he first started singing

- 418 A fable about foolish singers who pretend to great art but are incapable

- Lange Weise

- 425 The following songs written down here are in Michel Beheim’s Lange Weise, and this first one that is in here and in the melody, Michel Beheim composed it when he first began to write songs and relates that he had many who envied him because of his artistry in composition

- 438 The following ongs written here also are in the Lange Weise, but the rhymes are changed and not as disguised as in the previous ones, they are open, as can be heard in this text, as I have made a special text for it

- 446 This tells about the Turks and the (Christian) nobility

- Bibliography

- Index

Preface

This volume represents a selection of the songs of Michel Beheim (1420–ca. 1474).1 I have chosen only songs that illuminate Beheim’s personality and times: those that are of autobiographical, cultural, or political interest. I have left out his massive oeuvre of religious poetry, which deserves a volume (or two) of its own, as well as his more traditional love poetry (Minnesang), that is, the ones that posed no risk to his career at court.2 I have also omitted all songs in four melodies (Slecht guldin Weise, Trummetenweise, Gekrönte Weise, Hohe guldin Weise) that I found too intricate, indeed baroque, to do justice to in English.

I have also attempted throughout to imitate the original meter of the songs. This has occasionally led to minor discrepancies in translation, but I have also tried to maintain what I read as a sense of humor (and certainly sarcasm) in the songs.3

The melodies as transcribed in this volume are based on the interpretation of the translator, who is not a professional musician. I have attempted to convert the manuscript notes into a more modern notation. Given the debate surrounding the intended length of the MS notes,4 I have chosen to render the songs predominantly in quarter notes, with rests between the phrases. The software I used (Finale) insisted on imposing a time signature, so some of the rest lengths and slurs/tuplets may appear arbitrary. This is the result of removing the bar lines from what is basically a 4/4 rhythm. I make no claim to having created a score for performance.

Acknowledgments

Without the constant encouragement and support of Susan Allen and William C. McDonald, this volume would not have come about. I am deeply thankful to both. I am also indebted to the scholarly input of Mark Brill for guiding me through the intricacies of fifteenth-century monophonic music and that of Dianne McMullen for invaluable corrections and suggestions on the musical transcriptions. Any mistakes and infelicities in transcribing the melodies, of course, must be laid at the door of the transcriber. The prize for outstanding interlibrary loan digging goes to my daughter, Luisa Ogier, who found the most obscure sources for me. And gratitude is owed to Albrecht Classen for bibliographic corrections.

Special thanks go to Benjamin Esswein for explaining the Battle of Varna to me and helping with further sources. I am furthermore indebted to Laurel Plapp and her staff at Peter Lang for guiding me through the editing process.←xi | xii→

Introduction

The poet and court singer Michel Beheim was born on September 29, 14201 in Sülzbach near Weinsberg, which in turn is near Heilbronn in Swabia. Having the exact birth date for a fifteenth-century poet in an autograph manuscript is remarkable in itself, but it shows Beheim’s penchant for self-display as a public figure. As his great-grandfather had come to the area from Bohemia, the family acquired the name “Beheim,” and, following in his father’s footsteps, he adopted the trade of weaver. His family weaving business lay outside the urban, guild-dominated setting of Heilbronn and may thus have found itself in competition with the guilds, which has been used to explain his later animosity toward city burghers in general.2

Already as a teenager, Beheim discovered his talent as a composer of monophonic melodies and as a singer. His talent was recognized by Arch-chamberlain Konrad von Weinsberg, who brought him to court and extended patronage to him. This introduced him into court circles as a “gernder man” (a singer seeking a reward from the nobility), where his career would flourish, rising eventually to become the emperor’s poet and singer in Vienna.

By the early fifteenth century, the dominant form of song was the Meistersang, having developed from the earlier Spruchdichtung (sententious, moralizing songs). These poetic currents had washed away the Minnesang (love songs) of the high Middle Ages and, along with it, its veneer of noble artistry. Meistersang, like Spruchdichtung, was carried by the rising middle class and showed strongly religious and moralizing tendencies. Beheim, who belongs firmly among the ranks of the early ←1 | 2→Meistersingers, must be seen as a transitional figure between courtly song, which has the nobility as its audience, and the later Meistersang, which became an expression of urban guild culture, aiming at middle-class listeners. As focused on courtly life as he was, Beheim abhorred the urban Meistersingers’ recycling of old melodies with new lyrics; he expressly favored originality.

Beheim’s role at court probably extended well beyond singing and into the military realm. In his 20s, in Konrad’s service, he was undoubtedly still a soldier with a sideline as poet, even though he had by this time composed many of his Weisen (melodies). This brings us to the vexed question of how a weaver learned the techniques of Meistersang. Konrad von Weinsberg had a documented interest in the art, having in 1437 commissioned songs from one of the giants in the field, Muskatblüt, whom Beheim cites as his role model.3 The two may have met at Konrad’s court and formed a master-apprentice relationship. As Niemeyer has detected echoes of Oswald von Wolkenstein’s works in Beheim’s songs, and as both Konrad and Oswald belonged to the Order of the Dragon, Beheim could well have crossed paths with this nobleman-poet, as well.4 But it is also likely that he learned much during his years as a journeyman apprentice weaver.5

Konrad died in January 1448, leaving Beheim without a patron. According to song 22, Beheim arrived in Munich shortly thereafter, after “troubling times,” most likely Konrad’s death. His stay came soon after the birth of Albert6 IV (December 15, 1447), son of Albert III of Bavaria, about whom Beheim would compose a horoscopic poem a few years later.

His next patron was Margrave Albert Achilles of Brandenburg-Ansbach, who had most likely encountered Beheim at Konrad’s court and recruited him after Konrad’s death.7 For the next few years (1448–1450) ←2 | 3→Albert was engaged in a struggle with the free imperial cities of the south, especially Nuremberg. Albert took Beheim along to Heidelberg for the reconciliation talks of 1450, where soldiers from the free imperial city of Rothenburg ob der Tauber took Beheim prisoner and Albert had to ransom him. The anti-burgher animal fables (e.g., 54, 55, 318) stem from this period and were probably written for Albert.8 His attendance at Heidelberg, however, suggests that his role at Albert’s court had expanded into the representational, if not diplomatic range. We see this again in his next adventure.

Also in the summer of 1450 came an important event in Beheim’s life: a voyage to Norway (song 327). In addition to enjoying the honor of representing his patron,9 Beheim expressed relief at escaping the chaotic situation in war-torn Franconia. Along the way, he stopped off in Copenhagen and visited the queen, who wanted news of her parents and her uncle, Albert Achilles. Then began the lengthy and perilous journey by sea up to Trondheim for the coronation of Christian I of Norway on July 29, 1450. The sea voyage was undoubtedly perilous, and Beheim thoroughly dramatizes the events and probably borrows from other travel literature.10

Beheim’s relationship with Albert ended, for unclear reasons, in 1452, by which time he had composed eight of his twelve tunes, including the Hof- and Zugweisen.11 Thereafter he turned up at the court of the Wittelsbach Duke Albert III in Munich, to whom he had paid a visit some six years previously. This gives rise to the horoscopic song (22) about Albert’s son, Albert IV, whose sixth birthday fell in December. The stay in Munich did not last very long, as Beheim complains about lack of appreciation in songs 25 (not in this volume) and 26.

On May 29, 1453 occurred an earthshaking event, one that would occupy Beheim for the next decade, as it did most of his contemporaries: the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks. The following year we find Beheim on the way to the Regensburg Reichstag, probably in the retinue of Archduke Albert VI of Austria, where the problem of the Turks dominated ←3 | 4→the discussions. From this point on, Beheim composes song after song excoriating the nobility for its lack of action and encouraging a crusade against the Turks (98, 101, 104, 237, 238, 239, 328, 446).

Beheim may have met King Ladislaus the Posthumous, Duke of Austria and King of Hungary, in Prague in 1454, but was certainly in his service by mid-1455.12 The following year, Ladislaus assigned Beheim (in his capacity as soldier) to the forces of Ulrich II, Count of Celje, which were staving off a Turkish siege at Belgrade. Through treachery, Ulrich, who had been instrumental in making his protégé Ladislaus King of Hungary, was assassinated on November 9, 1456, in Belgrade as a result of a feud with the Hunyadis, a Hungarian noble family. According to Beheim (328), he himself was robbed of all his possessions by the rebelling Hungarians.

After the siege, Ladislaus returned to Prague, where he died on November 23, 1457. Beheim, however, had already left his service, possibly because of a court intrigue.

For a while, Beheim turned to Albert VI, Duke of Austria, brother and rival of Emperor Frederick. But somehow, a year later, possibly after offending a highly placed courtier,13 Beheim managed to join Frederick’s court in Vienna, where he stayed for six years as the “emperor’s poet,” despite his earlier relationship with his hated brother.

Those six years saw a great deal of upheaval in Vienna. First, Albert laid siege to Vienna from June to September 1461 (cf. song 112). Next, the citizens of Vienna rebelled against the emperor and assailed the Hofburg from October to December 1462. This last siege caused Beheim to write his scathing chronicle The Book of the Viennese, which describes the defense of the castle, the resulting famine, the treachery of the citizens, and the price put upon his head. A reconciliation was reached between the emperor and the Viennese residents in April 1465. But in the months thereafter, probably because of a court intrigue,14 Beheim was dismissed from ←4 | 5→the emperor’s service. Yet, for the rest of his life, he maintained the title of “the emperor’s poet.”

His sources of patronage in the following year are somewhat obscure. After a stay with Sigmund of Bavaria (song 102; not in this volume),15 he eventually landed at the Heidelberg court of the Wittelsbach Count Frederick I (the Victorious) of the Palatinate in the second half of 1468. Frederick had inherited the area around Sülzbach and was thus Beheim’s rightful lord.16 For Frederick he, along with one of Frederick’s clerics. composed a rhymed Chronicle of the Palatinate, but largely a panegyric to Frederick, in 1472.17 For Frederick, he engaged in his last battle as a soldier, on August 26, 1471.18

This signals the end of his career as a court singer. In 1472 he returned to his hometown of Sülzbach, where he became Schultheiß (mayor) and occupied a house that bore his family crest.19 Under unclear circumstances, he was later murdered (a Sühnekreuz, a marker of repentance placed by the murderer or the murderer’s family, once stood at the scene of the crime; the date breaks off after MCDLXX and is thus inconclusive).20

Beheim spent his career composing and performing the traditional monophonic music of the early fifteenth century. By the end of his career, polyphony had made inroads into court music, and, in Beheim’s opinion, the newer generation of Meistersinger could not hold a candle to the greats of the past, especially because they (as is standard in urban, guild-based Meistersang) took existing tunes and put their own words to them. Beheim took great pride in the twelve melodies he had composed for his own use. His later songs complain bitterly about the decadence of the profession and the rivalries with other singers. But there is hardly another poet of this era (with the striking exception of Oswald von Wolkenstein) who took such care in preserving his legacy. We have almost all his songs written either in ←5 | 6→his own hand or in a version that he supervised, in three main manuscripts that he continually revised.21

Beheim styled himself as a fürtreter, literally “one who steps forward” to sing. As such, he felt a duty to warn, provoke, and speak truth to power. He took the roles of counselor, prophet, theologian, moral guide, historian, and (not least) entertainer. That his attitude was not universally accepted shows up in his succession of court appointments, some of which he left under a cloud.22

Unlike those of the early Minnesänger, who were widely anthologized, Beheim’s ca. 450 songs found little reception after his death. This may have to do with the specificity of his oeuvre; his relationship with his courtly audience bound his work to a limited time and circle, as much as he tried to preserve it for posterity.23 His songs were composed for consumption by the court, rather than for private amusement, as with Oswald. The content of the songs included here fall into a few broad categories:

Details

- Pages

- XII, 328

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800795334

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800795341

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800795358

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781800795327

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18532

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (November)

- Keywords

- fifteenth century Michel Beheim court poetry The Songs of Michel Beheim

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2022. XII, 328 pp., 1 fig. col., 7 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG