One Dragon, Two Doves

A Comparative History of the Catholic Church in China and in Vietnam

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword (He Guanghu)

- Foreword (Michael Nguyen)

- Introduction Comparing the Churches of China and Vietnam

- Chapter 1 The Pioneers: Matteo Ricci and Alexandre de Rhodes

- Chapter 2 The First Martyrs: Huang Mingsha and Andrew of Phu Yen

- Chapter 3 Outstanding Christian Women: Agnes Le and Agatha Lin

- Chapter 4 Authors of Christian Literature: Giulio Aleni and Geronimo Maiorica

- Chapter 5 Dominican Students in the Philippines: Luo Wenzao and Vicente Liem

- Chapter 6 Priests from the East in Europe: Zheng Manuo and Philiphe Binh

- Chapter 7 Western Studies in the East: Li Ande, the Colegio de São Paolo, and the Seminary of St. Joseph

- Chapter 8 Foreign Affairs Secretary of the Emperor: Fr. Poirot and Fr. Pigneau

- Chapter 9 Successful Messengers of the Faith: Bp. Dufresse and Bp. Longer

- Chapter 10 Mandarin Christians: Xu Guangqi and Hồ Đình Hy

- Chapter 11 Officials Cooperating with Foreigners: Lê Văn Duyệt and Zeng Guofan

- Chapter 12 Catholic Reformers: Nguyễn Trường Tộ and Ma Xiangbo

- Chapter 13 Xenophobic Mandarins: Tôn Thất Thuyết and Yu Xian

- Chapter 14 Encyclopedists and Editors: Trương Vĩnh Ký and Li Wenyu

- Chapter 15 Papal Representatives and the Reform of Seminaries: Celso Costantini and Costantino Aiuti

- Chapter 16 Catholic Prime Ministers: Nguyễn Hữu Bài and Lu Zhengxiang

- Chapter 17 Inculturation of Religious Art: Trần Lục and Liu Bizhen

- Chapter 18 The First Bishops: Nguyễn Bá Tòng and Zhu Kaimin

- Chapter 19 Erudite Theologians: Hồ Ngọc Cẩn and Xu Zongze

- Chapter 20 Pioneers of Indigenization: Fr. Cadiere and Fr. Lebbe

- Chapter 21 Political Activists: Ngô Đình Thục and Yu Bin

- Chapter 22 Christian Literature: Su Xuelin and Đỗ Đình Thạch

- Concluding Observations

- Bibliography

- General Index

- Index of Personal Names

- Indices of Places and Terms

- Index of Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese Books

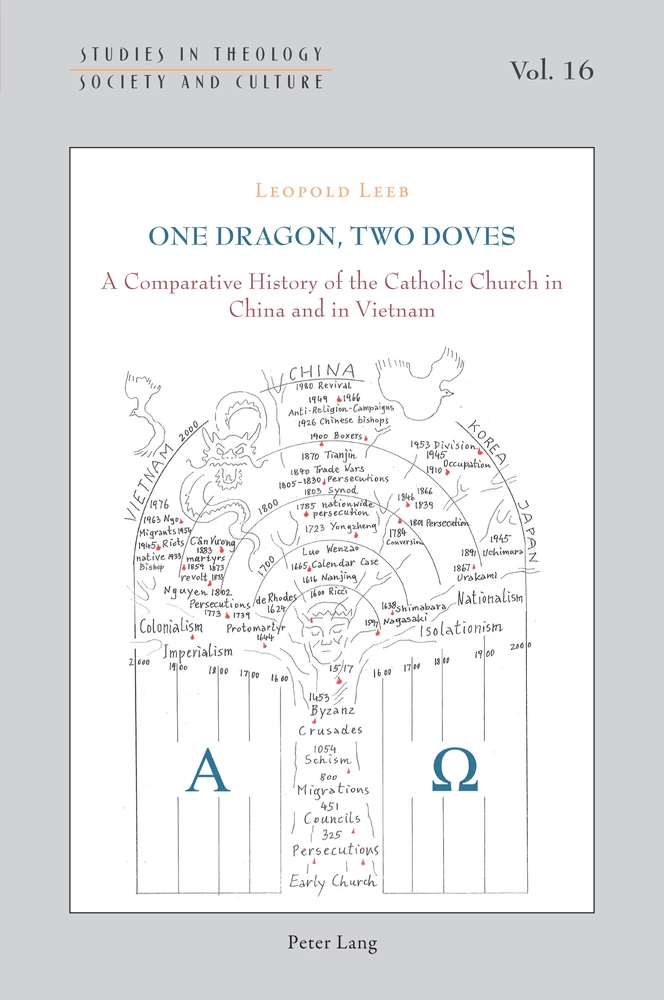

- Synoptic Chart of Ecclesiastical History in China, Vietnam, Japan, and Korea

- Series Index

Figures

Figure 14.1. Petrus Trương Vĩnh Ký.

Figure 14.2. Philomena Huang Bolu.

Figure 14.3. Laurentius Li Wenyu.

Figure 17.1. Phát Diệm, Vietnam; Tran Luc’s church, completed in 1899.

Figure 17.2. Guiyang, China: The North Church, completed 1876.

Figure 19.1. Bishop Dominic Hồ Ngọc Cẩn.

Figure 19.2. Father Joseph Xu Zongze.

He Guanghu

Foreword

According to political geography, China, Korea, and Japan are usually denoted by the term “East Asia,” whereas Vietnam is subsumed under “Southeast Asia,” together with Cambodia, Malaysia, and other countries. In fact, seen from some other viewpoint Vietnam actually also belongs to “East Asia,” because in terms of cultural history, this nation is a part of the “culture circle of the Chinese script” or of the “circle of Confucian culture.” It is also noteworthy that the popular Buddhist tradition of Vietnam does not belong to the Hinayana, but to the Mahayana school, which is also more popular in China, Korea, and Japan. Therefore, if we study historical, cultural, and religious questions, Vietnam is in a position where a comparison to China is possible, and in fact this comparison should really be made. A comparative research will not only be very interesting, it will also be greatly revealing and meaningful.

It is a deplorable fact that Chinese scholars have conducted very few comparisons between China and Vietnam, be it in the area of comparison of cultures, comparison of religions, or comparison of politics. Therefore this new book by the “sinologist from outside” Leopold Leeb has become another very rare and unique achievement!

For this kind of academic research we should accumulate a big mass of materials and documents. This work by Leopold Leeb has in the first place attempted to face up to this troublesome and arduous task, which takes so much time, energy, and patience, and we should really thank him for that!

In the various chapters of his book he has also raised many inspiring and important questions which deserve our further investigation and a search for answers. As for myself, I have discovered many new questions, and even the basic materials are providing many insights and issues for further reflection!

←xi | xii→I just choose a few examples at random. It seems that in China everybody has this impression: The Boxer movement originated in Shandong and spread from there to other regions in north China, thus in Shandong one would expect a large number of “Boxers,” and one would also expect that in Shandong more people would have been killed by them than elsewhere. However, the comparison of materials provided in this study will cause our surprise and reflection: During the time of the Boxer unrests only one single foreigner was killed in Shandong, whereas in the same period almost 200 foreigners were killed in Shanxi Province (among them women and children), and in Shanxi more than 10,000 Chinese people were killed by the Boxers! The reason for this unexpected phenomenon is quite simple: The main administrators of the two provinces (Yuan Shikai in Shandong and Yu Xian in Shanxi) had very different attitudes! Everybody knows that the popular feelings of the locals in these two provinces were rather similar. This example shows at least one thing: The personal attitude and understanding of the mandarins played a vital and decisive role!

It is likewise a well-known fact that during the “New Culture Movement” (xin wenhua yundong) in the early decades of the twentieth century many Chinese scholars deplored that the Chinese characters do not provide accurate phonetic symbols and thus are hard to learn. In addition, the cumbersome script would also form an obstacle to social integration and to cultural progress. Some of these scholars argued for the advantages of a phonetic script, and they devoted much time and energy to change the writing system of China although the project was abandoned before it could become a success. In the question of a modern script the present study also provides an important comparison, namely the efforts of several nations of East Asia to create a phonetic script (so that the pronunciation and the written symbols would converge and thus the script would be easy to read and to write). Japanese authors used a new script in the tenth century (Murasaki Shikibu), the Sejong King of Korea created a script in the fifteenth century, and Vietnam had an alphabetic script in the seventeenth century (elaborated by de Rhodes and others). In the nineteenth century this script was already used for printed books and periodicals! If Vietnam was not tossed and torn by long-term wars, would its society and culture not greatly transcend the progress reached today? As to the causes of the huge progress of Japan and Korea, there are of course social and political ←xii | xiii→reasons, but their language reforms must certainly also count as a meritorious achievement.

At this place I must confess that some of my own long-cherished views were actually the result of my ignorance. I have always admired the multi-talented Matteo Ricci and his manifold achievements, thus I thought his contributions to the cultural exchanges between East and West are unique or at least very rare among missionaries in Asia. After reading this book I came to realize that the achievements of Fr. de Rhodes actually surpass those of Matteo Ricci in some ways, because the most basic foundation for cultural dialogue and exchanges is in fact the communication and integration of the script.

Many Chinese people believe that the following slogan is true: “One more Chinese Christian convert means a Chinese less!” (Duo yige Jidutu, shao yige Zhongguoren!) I have always doubted this phrase: Was Ma Xiangbo not a Chinese? Was Yan Yangchu not a Chinese? Was Lin Yutang not a Chinese? Was Sun Yatsen not a Chinese? This book reminds us that a further fact should make us suspicious of the phrase above: During the Peace Conference of Paris in 1919 the Chinese delegates protested the pressure from the Allied Forces and Japan and refused to sign the convention, and those two delegates who refused to sign were actually Christians, namely the Catholic Lu Zhengxiang and the Protestant Gu Weijun (Wellington Koo)!

When we reflect on this book we will also discover that sometimes “one more Christian” will mean one more loyal friend of China, for example, Fr. Vincent Lebbe who loved China more than his own fatherland, and who resisted the French government for the sake of China. Fr. Lebbe also fought against the Japanese on the side of China. Sometimes “one more Chinese Christian convert” will mean one more outstanding Chinese personality. For example, if Su Xuelin and Yu Bin were not Christians, their talents and achievements would probably not have been so brilliant and so admirable!

In China there is another popular misconception: In the first half of the twentieth century the churches in China were totally controlled by the westerners, because all missionaries relied on the western imperialism, and the indigenization of the churches was the result of the “Patriotic Movement” of the 1950s. This book reminds us that the main objective of the “papal delegate” Bp. Costantini was to promote the indigenization of ←xiii | xiv→the Catholic Church in China. This is also a well-known historical fact. However, it is much less known that in the 1920s the Chinese Bishop Hu Ruoshan not only became an apostolic vicar, but that he even presided the consecration of a foreign priest (Fr. Defebvre) as bishop! Only few Chinese may know about this important detail!

For the past 2,000 years the relations between China and Vietnam were so intimate and manifold and yet so complicated – in some periods the two nations were almost united or had a tributary relation, and in other periods they were inimical to each other and even fought wars. Let us not talk about the distant past. In a rather recent period there were many Vietnamese “boat people” who found shelter in Hong Kong, and this became a rather serious problem for the administration of Hong Kong. When I was in Hong Kong in the year 2000 I also witnessed the different reactions to the canonization of several hundred Catholic Chinese and Vietnamese saints by the curia in Rome, and I was very touched by the event.

If now I can see that this ground-breaking work comparing the historical developments of the Catholic Church in China and in Vietnam is published in Hong Kong, I am deeply moved again, and I want to express my gratitude to the author and to the publishing house. Let us thank them for their comparative historical perspective, their efforts, and their thoughtful research!

Carlyle, Pennsylvania

2021

Michael Nguyen, SVD

Foreword

Christianity through Alopen arrived in the capital Chang’an of the Tang Dynasty in 635. Later, Matteo Ricci set his foot on Macau’s soil in 1582. Likewise, Christianity through Inekhu arrived in North Vietnam in 1533. Later, Alexandre de Rhodes landed in Central Vietnam in 1624. Historical conflicts between the West and the East in the past indicate that these Western missionaries did not enter vacant lands in the Far East. They actually encountered one of the great civilizations in the world. Indeed, the Chinese Rites Controversy and the nearly three centuries of persecution in Vietnam took place because the core of Christianity contradicts the cores of the religiosity of Chinese rituals and the Vietnamese ancestor veneration. This contradiction still has a significant impact in China and Vietnam, for Christianity remains a minority religion in both countries in the third millennium.

Yet in spite of being suppressed in China and Vietnam, Christianity does not die out, but survives in both nations. More than that, Christianity is able to contribute its unique elements to both cultures. Concerning the national script, Vietnam’s case is more obvious.

The most significant contribution that Christianity contributes to Vietnamese culture is the Romanized script, known as the Quốc ngữ. Scholars suspect the existence of an ancient Vietnamese script found on many artifacts dated before the arrival of the Chinese. Under the influence of Chinese domination, the Chinese script became the common script in Vietnamese society until the birth of the Romanized script, the fruit brought forth by the teamwork comprised of Jesuit missionaries and early Vietnamese faithful. Because of its convenience (easy to read and write) and also with the support from the French colonial rulers, the Romanized script was embraced by the Vietnamese intellectuals who in turn promoted and spread the Quốc ngữ among themselves and to the people. The two famous ←xv | xvi→Catholic figures who introduced the Romanized script to the Vietnamese are Petrus Trương Vĩnh Ký and Paulus Huỳnh Tịnh Của, who were the Director and the Chief Editor relatively of Gia Định Báo (1865–1910), the first newspaper written in the Romanized script. In 1906, Emperor Thành Thái issued a decree to allow the Romanized scrip to be taught in schools and the official language of the state examinations. And today, the Quốc ngữ is the official language and script in Vietnam. In spite of its many advantages, the Quốc ngữ also hinders the Vietnamese in the contemporary society to read numerous writings written by their ancestors in the Chinese script and the Nôm script.

Before the arrival of Christianity Vietnam was a polygamous society. A man, if his wife failed to bear him a son, could marry another woman in order to ensure the continuity of the family line. In other cases, if the financial situation allowed it, a man could also marry several wives. However, since Christianity was introduced to the Vietnamese people, this cultural practice was challenged by the Christian teaching regarding the law of marriage. Christianity was persecuted in Vietnam for nearly three centuries. The church teaching against the practice of polygamy was one of various reasons that led to this protracted persecution. Vietnamese society eventually changed its marital norm from polygamy to monogamy.

The contribution of Christianity to Vietnamese society does not stop at inventing the Quốc ngữ and transforming the Vietnamese cultural practice concerning marital norms. Actually, Christianity also dialogues with Vietnamese culture. The construction of the Cathedral Phát Diệm in North Vietnam is a concrete example of this inculturation. Phát Diệm church is constructed by stones in a cultural shape of a đình, a traditional temple of the Vietnamese indigenous religion. Prior to the arrival of the triple religion (Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism), the people in Vietnam have already cultivated their own religion, which can be summarized as the cult of spirits. At the top of this spirit-hierarchy is Venerable Heaven/Ông Trời, the Supreme Being, who is the Almighty. Besides worshipping Ông Trời, residents of a village also venerate a local spirit of their own. This guardian of the village is venerated at their đình. When Fr. Trần Lục proposed the façade of Phat Diem Cathedral in the shape of the Vietnamese ←xvi | xvii→religion temple, he stated a rather clear contextual theology, that is, in this inculturated church, the Guardian of the Vietnamese people or God resides.

Not only in the field of architecture but also in the realm of literature Christianity inspires the Vietnamese. The famous poet Hàn Mặc Tử is a figure that fits this category. Hàn Mặc Tử in his own Vietnamese poetic style composed the two inculturated poems, “Ra Đời/Nativity” and “Thánh Nữ Đồng Trinh/Our Lady the Holy Virgin.” Inspired by these two accounts, the Infancy Narratives and the Annunciation, Hàn Mặc Tử sophisticatedly wrote these two poems that profoundly reflect the Vietnamese mindset in the Romanized script.

Before Hàn Mặc Tử, Alexandre de Rhodes and his Vietnamese assistants already laid the first stones for the road to the Vietnamese contextual theology through the invention of Ngắm Đứng/Standing Meditation which is commonly practiced during Lent. Using the musical tones of the Vietnamese operas, Chèo or Tuồng, Alexandre and the team composed Ngắm Đứng or the 15 Stations of Cross which enable the Vietnamese faithful to meditation on Jesus’ passion in their familiar chanting music.

Vietnam and China share with each other not only the border but also the culture. Under more than 1,000 years of influence from her northern neighbor, Vietnam embraced and adopted the core teachings of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism into her own Indigenous religion. This phenomenon did not happen to Christianity. Christianity entered Vietnam in 1533 and blossomed after the arrival of the Jesuits of whom Francis de Pina and Alexandre de Rhodes are famous figures. Christianity enjoyed fast growth, as Rhodes recorded in his diary the number of 300,000 Vietnamese Catholics in 1650. However, this religion soon faced nearly three centuries of persecution because its religious core was contradicting the core of the Vietnamese Indigenous religion, that is, ancestor veneration. Christianity was indeed named as a false religion/tả đạo by the Vietnamese emperors. The two words tả đạo were carved on the faces of the Vietnamese Catholics arrested by the Vietnamese mandarins. Nevertheless, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, Christianity continues to enter the territory of the Dragon-Vietnam, challenges negative elements of the culture, and in turn contributes its own values to enrich the values of Vietnamese society.

Stories about the development of the church in Vietnam presented above – only a few of the many stories discussed in Leopold Leeb’s ←xvii | xviii→book – explain why the author names his book “One Dragon Two Doves.” Indeed, very similar to the Chinese dove, the Vietnamese dove has “found ways of survival and development in a hostile or at least challenging environment” (see Leeb’s introduction).

Divine Word College

Epworth, Iowa

September 2021

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 338

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800797970

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800797987

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781800797963

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19476

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (October)

- Keywords

- Chinese Catholic Church Vietnamese Catholic Church Catholicism in Southeast Asia Christianity and Confucianism biographies of Christians missionaries in East Asia One Dragon Two Doves Leopold Leeb

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2022. XVIII, 338 pp., 11 b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG