Summary

This book contains a detailed introduction to its subject. Part One presents relevant ideas about openings in rhetorical and poetic theory from Aristotle to Julius Caesar Scaliger. In drawing on these ideas—and without making too strong a claim about direct or indirect influence—author Joel Benabu constructs a theoretical framework for Shakespeare’s opening strategies. Part Two, comprising the main section of the book, explores different strategies for constructing an opening in the Shakespearean plays selected for analysis. The conclusion takes a broader perspective on the theory of Shakespeare’s construction of openings explored throughout the book.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part One Relevant Terminology about Openings in Classical and Neoclassical Theory

- Part Two Tracing Shakespeare’s Composition of an Opening

- Chapter 1 Richard III

- Chapter 2 The Merry Wives of Windsor

- Chapter 3 Twelfth Night

- Chapter 4 Romeo and Juliet

- Chapter 5 Hamlet

- Chapter 6 Othello

- Chapter 7 Macbeth

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The ideas presented herein are the culmination of many years of research on Shakespeare’s play-openings, tracing their lines of composition in the play-text. In assembling them into a book, I have benefited from the financial assistance of several institutions, especially in the earlier stages of my research. A special thanks goes to the Centre for Drama, Theatre & Performance Studies at the University of Toronto for a scholarship as well as for the scholarly environment to conduct this piece of research. I am also grateful to the editors of Theatre Topics, Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, and Rhetoric Review for allowing me to rework in this book some of the material I published in previous years. I am deeply grateful to my father for his intelligent suggestions. His support in preparing the manuscript for publication cannot be overstated. I also wish to acknowledge Jill L. Levenson’s steadfast commitment, continued encouragement, and invaluable suggestions in the early stages of my research.

On a personal note, I owe my wife, Karen Gilodo, a huge debt of gratitude. Her encouragement has been unwavering throughout the period of my research as in the writing of this book.

INTRODUCTION

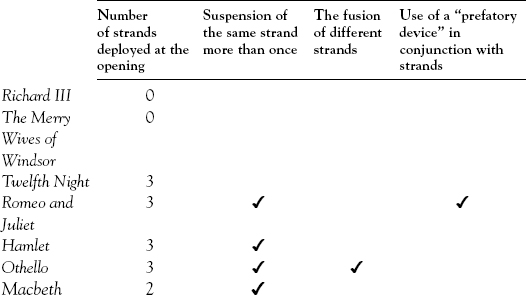

This book sets out to investigate how Shakespeare constructed the opening of a play. Specifically, it illustrates how Shakespeare has structured an opening in a fairly direct manner in Richard III’s initial monologue; how he uses the preludic mode in The Merry Wives of Windsor; and how the playwright elaborates a sophisticated structure of the opening in Twelfth Night, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth. The focus falls on how these play-openings were composed, how they function and how they were communicated by the playwright through his play-texts. Therefore, the book does not refer to past productions, unless these can shed light on the problematics of composing an opening. Furthermore, the limited scope of this book excludes any sweeping claims about the development of Shakespeare’s opening strategies in the entire canon.

Strands of Action

Through my research, I discovered that Shakespeare often postpones the development of the main action at the opening of a play. And I have termed the device he deploys in doing so “strands of action.” In ←1 | 2→order to elucidate the mechanics of the above-mentioned device, and basing myself, specifically, on Julius Caesar Scaliger’s recommendations as to how an opening should function in poetic composition (see pp. 27-28), I call attention to a series of subsidiary actions that are only partially developed at the play’s opening, and that serve to immerse spectators, principally through delaying the development of the main action, thus arousing spectator curiosity as to when the main action will take off. Moreover, with the passage of time these strands form an interpretative frame, or a cognitive pattern, through which spectators are able to obtain and process information (Kinney, xv). Identifying the strands of a play-opening, therefore, is useful in the analysis of Shakespearean plot composition, even though spectators are likely never to be aware of their identity as such. The ways in which Shakespeare reworked strands of action, over and over, at the openings of both tragedies and comedies, are demonstrated in Part Two. It is the mark of a playwright whose creativity was not bound by any rudimentary formula.

The strands of an opening may sometimes correspond with a scene division, as in Twelfth Night, for instance; but it is not essential that they do so, as in Othello and Macbeth (see pp. 103-126). Furthermore, whereas a scene change is typically marked in performance by the characters clearing the stage, no such requisite applies to a strand of action. In fact, since scene divisions do not appear consistently in the early quartos or even in the Folio of 1623, we may assume that Shakespeare never marked them in his manuscript.1 A strand of action, therefore, constitutes a structural unit relating to the composition of a play, and to the opening specifically.

Strands of action may be introduced successively; furthermore, a strand may be suspended by the introduction of a new strand and developed further when it is taken up again (as in Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, and Macbeth, but not Twelfth Night); and a strand can also present an apparent resolution of the action, as in Romeo and Juliet (see pp. 71-84), possibly with the intention to mislead spectators. Strands usually unfold in a single location, contain the same characters and often share tenuous links or points of contact, such as an allusion to ←2 | 3→a character or an event; but it is essential that each strand introduce an independent action or its development. The opening of a play is not complete, therefore, until the suspended strands trigger the main action(s) and this may be created in a variety of possible combinations (e.g., in Romeo and Juliet the strands appear preceded by a prologue and the main action only takes off in the last scene of Act One).

The chart that follows illustrates the number of strands deployed in the plays I discuss:

Narrative scholarship contributes to the study of strands of action by illuminating the “deep structures” of early modern plot construction. Barbara Hardy has argued, along similar lines to David M. Bevington (4), that Aristotle’s pronouncements on the elementary structure of “plot” are, in large part, incongruous with Elizabethan drama, finding a complex interplay between narrative forms that gives rise to the narrative whole.2 Hardy maintains that the sequences of early modern plays may relate to one another structurally, thematically, and rhetorically, even though these internal relations are often extremely difficult to decipher because of a diversity of forms (13). This idea has found favour with other Shakespearean scholars who have tested it in their ←3 | 4→respective analyses of Shakespeare’s plays. For instance, in “Echoes Inhabit a Garden: The Narratives of Romeo and Juliet,” Jill L. Levenson has extended Hardy’s argument through an analysis of narrative forms in Romeo and Juliet. Referring to the deep structure of narrative in the second quarto of 1599, she writes: “structural repetitions of all kinds can interrupt a given series: one or more related sequences, whole or fragmentary, may be ‘interlaced,’ ‘imbricated,’ within the main sequence” (40–41). Later she adds: “In view of these complexities... it is no wonder that theorists are questioning concepts of narrative opening, closure, and linearity” (41).

While the openings of Romeo and Juliet, Twelfth Night, Hamlet, Othello and Macbeth may involve the introductions of “a story or fragments of a story” (Hardy, 13), they do not seem to display an interplay of what Levenson describes above as “structural repetitions” that correspond to each other dialectically in a manner that dissolves the distinctions between mimesis and diegesis. Instead, each opening fulfills the delaying function that is intrinsic to the process of spectator immersion, and it may take the form of a diegetic device (like a prologue).3 Therefore, in preference to “narrative strand” used by the scholars quoted above, I believe the concept of “strand of action” defines more accurately the compositional strategy used by Shakespeare and stresses the discontinuity of the suspended actions at the start of a play.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 144

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433187841

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433187858

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433187865

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433187834

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18327

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2023 (February)

- Keywords

- Shakespeare theatricality play-openings techniques of composition the organization of plot Stage directions explicit and implied Dramatheory RhetoricalTheory Shakespeare and the Strategiesof anOpening Joel Benabu and Poetic Theory

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2023. XII, 144 pp., 1 table.