The Verbal Aspect Integral to the Perfect and Pluperfect Tense-Forms in the Pauline Corpus

A Semantic and Pragmatic Analysis

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Advance Praise

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Series Editor Preface

- Author’s Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Introductory Remarks

- 2. Linguistic Investigations into the Greek Language

- 3. Application of Linguistic Investigations to Exegesis

- 4. Thesis Statement

- 5. Chapter Organisation

- Overview of Verbal Aspect Studies as Related to the Greek Perfect and Pluperfect Tense-Forms

- 1. Introductory Remarks

- 2. The Development of Verbal Aspect as a Term for Grammatical Analysis

- 3. Verbal Aspect as Related to the Greek Perfect and Pluperfect Tense-Forms

- 4. Conclusion

- A Way Forward

- 1. Introductory Remarks

- 2. Consideration of Methods

- 3. Complexity of the Verbal Aspect for the Perfect Tense-Form

- 4. Implications for Complex Aspect

- 5. Conclusion

- The Complex Aspect of the Perfect Tense-Form in the Pauline Corpus

- 1. The Verbal Data from the Pauline Corpus

- 2. Conclusion

- Comparing the Pauline Corpus to a Diachronic Corpus of Epistolary and Moral Literature

- 1. Corpus-Based Approach

- 2. Defining the Limits of Both Corpora for Analysis

- 3. Purposes of the Greek Diachronic Epistolary and Moral Literature Corpus

- 4. Issues in the Greek Diachronic Epistolary and Moral Literature Corpus

- 5. Contents of the Greek Diachronic Epistolary and Moral Literature Corpus

- 6. Necessity for Corpus Approaches to Answer Certain Linguistic Questions

- 7. A Review of the Corpus Data

- 8. Conclusion

- Conclusion

- 1. Summary and Restatement of the Thesis

- 2. Contribution to Knowledge

- 3. Limitations of the Research

- 4. Suggestions for Further Research

- Bibliography

- Appendix A: Rationale and Purpose of the Appendices

- Appendix B: Chart of Morphemes

- Appendix C: Chart of Stem Count

- Appendix D: Chart of Stems by Frequency

- Appendix E: Chart of Context

- Appendix F: Chart of Adverbial Modification of Stative Perfects

- Appendix G: Chart of Adverbial Modification of Eventive Perfects

- Appendix H: Adverb Frequency Data

- Appendix I: Key Adverbs

- Appendix J: Chart of Adverbial Modification of Perfects used in Citational or Referential ways

- Appendix K: Chart of Pauline Corpus Examples with Perfects

- Appendix L: Chart of Analysis Corpus Examples with Perfects

- Appendix M: Chart of Selected Verbs Found in the Perfect Tense-Form within the Pauline Corpus Fully Conjugated

- Author Index

- Text Reference Index

- Subject Index

- Series Index

Figures

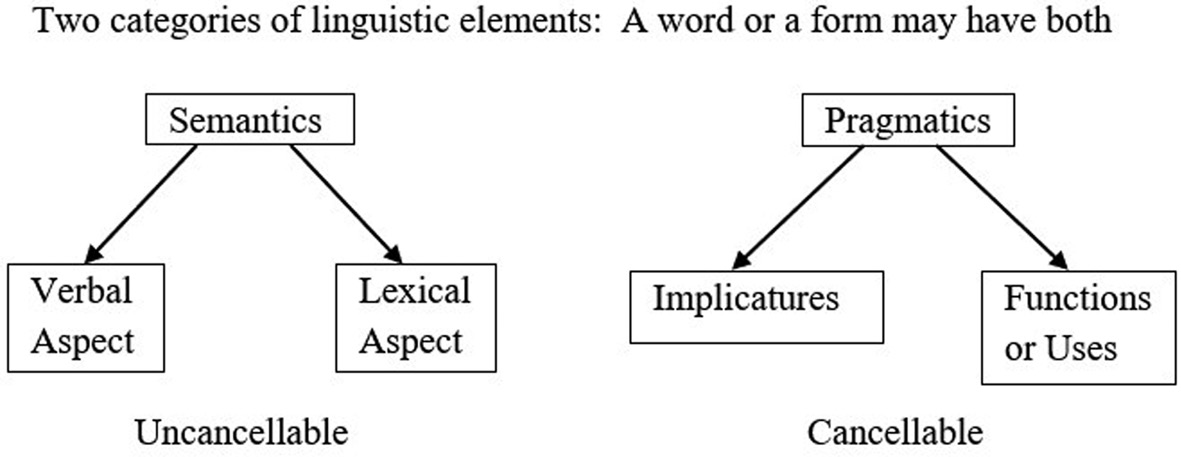

Figure 1: Categories of linguistic elements

Figure 2: Contrasting two aspects using a point-of-view

Figure 3: Fanning’s Aspectual System

Figure 4: Olsen’s Aspectual System

Figure 5: Campbell’s Aspectual System

Figure 6: Porter’s Aspectual System

Figure 7: Different forms of the Greek Perfect

Figure 8: Interruptibility of the previous clause

Figure 10: Stem comparison using four verb types

Figure 11: Reduplication syllable types on a cline

Figure 12: Reduplication effects situated along a cline

Figure 13: The two-fold path for lexemes developing into imperfectives

Figure 15: Timeline of the synthetic Greek Perfect

Figure 16: The synthetic Greek Perfect in several time periods

Figure 17: The synthetic and periphrastic Perfects showing mirroring of components

Figure 18: Comparison between Ancient and Modern Perfects←ix | x→

Figure 19: Adverbs of Perfects in Perfect + Relative Clause Constructions

Figure 20: Adverbs of Perfects within Relative Clauses

Figure 23: Frequency of the Categories as a Ratio

Figure 24: Perfect forms of οἶδα

Figure 25: Inter-relatedness of “see” and “know”

Figure 26: Aorist forms of εἶδον

Figure 28: Bar Chart of Wordcount by Century Divided by Genre

Figure 29: Bar Chart of the Total Wordcount by Century

Figure 30: Bar Chart of Total Wordcount by Genre

Figure 31: Comparison of the Perfect tenses in the subcorpora

Figure 32: Comparison of οἶδα usage in the subcorpora

Figure 33: Comparison of supplemental uses of Perfects across the subcorpora

Series Editor Preface

Successfully defended as a doctoral dissertation at the University of Manchester in 2020, this work breaks new ground in its understanding of the Greek synthetic Perfect tense-form (including the Pluperfect) distributed prominently in the Pauline corpus. While most theories argue that a single aspect is conveyed by the tense-form—usually the stative, the imperfective, or the perfective—Dr Sedlacek presents a detailed case for a complex aspect: the morphology of the synthetic Perfect tense-form, he asserts, contains both (1) a lexical core that points to perfectivity of the event (mirroring as it does the Aorist tense-form), and (2) a reduplicant grammaticalising imperfectivity that focuses on a state relevant to the event, and that relevance may be to the grammatical subject or to an object. Both of these aspects remain in tension in the Perfect tense-form. Neither aspect is ever entirely cancelled, but the complex model that Sedlacek advances allows scope for a variety of emphases. The author gains methodological control by comparing the Perfect and Pluperfect tense-forms in the Pauline corpus with uses in Greek letter writers from 400 BCE to CE 400. This work will become part of the “must read” list for scholars working on the Greek Perfect and, indeed, on aspect theory.

D. A. Carson

Trinity Evangelical Divinity School

Author’s Preface

The idea for a project involving verbal aspect began years before when I was in my graduate program of study at Cincinnati Christian University, where I earned a Master of Divinity degree. The majority of my coursework there was in biblical languages and exegetical methods, and the role of Linguistics upon grammar was emphasised as a component of exegesis. William Baker introduced the works of Stanley Porter, Buist Fanning and Constantine Campbell to me in my Greek exegesis classes around 2007, and later asked me to review the Basics of Verbal Aspect, by Constantine Campbell when it was available from Zondervan in 2008. During my final year of my graduate program in 2009–2010, I had the opportunity to teach New Testament Greek at God’s Bible School & College, where I had earned my undergraduate degree much earlier. Philip Brown, my immediate supervisor, engaged me frequently with discussions about issues raised in the works by Porter, Fanning and Campbell.

It was at that time I realised that the largest area of incompatibility between the three works lies in the application of verbal aspect to the Greek Perfect tenses. Additionally, I saw a different way forward to answer the problem of the Perfect. After graduating, I worked four years at Cincinnati Christian Schools teaching New Testament in High School. During this time, I reread the works by Porter, Fanning and Campbell and read much of the literature on verbal aspect ←xiii | xiv→and Perfect tenses in detail. After processing the relevant literature, I began to apply to PhD programs where I could develop my ideas more fully and put my research together. I participated in exegesis seminars for postgraduate researchers at Nazarene Theological College in preparation for a research programme. Once admitted into the PhD process, I received further development in Corpus Linguistics modules and seminars from both Lancaster University and the University of Birmingham, which together inform the method of this thesis. The courses from both of these institutions developed familiarity with current tools and practices in corpus linguistics along with a theory of corpus design.

Early drafts of most of the portions of the developing research were presented at Eastern Great Lakes Biblical Society, Stone-Campbell Journal Conference, Midwest Region Society of Biblical Literature Meeting, British New Testament Conference, and International Conference on Greek Linguistics. Two of these presentations are now published as peer-reviewed articles. In addition to the above conferences, I attended conference sessions on Linguistics or Pauline Literature at Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting, The Evangelical Theological Society, Tyndale Fellowship, The Chicago Linguistic Society, The Ehrhardt Seminars, and other seminars in the School of Arts, Languages, and Cultures at the University of Manchester.

This study identifies the verbal aspect for the Greek synthetic Perfect tense-form found in the Pauline epistles. The specific morphological components in the reduplicant and in the lexical core of the Perfect tense-form are used to construct a complex aspect relying upon Grammaticalisation. Diachronic considerations are maintained throughout the analysis. Criticism of the literature shows where either the nature of verbal aspect or the identity of the aspect for the Perfect tense-form is unclear. Several arguments point uniformly to a complex aspect for the Greek Perfect. Selected examples from the Pauline corpus are then analysed to test the complex aspect. A corpus-based study is defined and the use of the Perfect tense-form within the Pauline corpus is compared against a diachronic epistolary and moral literature corpus that results in the placement of the Greek synthetic Perfect tense-form on the respective grammaticalisation clines belonging to reduplicants and to perfectives equally. The comparison between Paul and Greek letter writers from 400 BCE to 400 CE shows that Paul uses the Perfect embedded within supplemental clauses more often than other writers. Paul also employs a greater variety of active lexemes in that role than other writers examined.

This study concludes that the verbal aspect for the Greek synthetic Perfect tense-form is complex, involving two verbal aspects, each related to a different part of the verbal complex. The reduplicant of the Perfect tense-form is imperfective, ←xiv | xv→and places that aspect upon a state. This state may be relevant to the grammatical subject or to an object. The lexical core is perfective, and places that aspect upon an event relevant to the lexeme. The complex aspect argued in this work best explains the wide range of Perfect uses, and accounts for the diachronic history of this tense-form shifting its focus from present-like stative usages to past-like eventive usages.

Many people and entities mentioned next provided assistance toward the development of this project. First of all, I thank Stanley Porter, Buist Fanning, and Constantine Campbell for producing such engaging works on verbal aspect for the Greek language, which provided much thought for this project. I am indebted to their contributions for my own interest in the Greek Perfect, and to William Baker and A. Philip Brown, II, for emphasising to me the importance of their works. Secondly, I thank William Baker, Tom Thatcher, Kent Brower, Sarah Whittle, and Svetlana Khobnya for encouraging me to pursue a PhD in this area, and for placing value on this project. Thirdly, I thank the institutions that have shaped me for combining a linguistic approach with biblical exegesis. I thank God’s Bible School & College and especially Robert England for generating in me an initial love for the Greek language. I thank Cincinnati Christian University and especially William Baker and Daniel Dyke for exposing to me the role for Greek language studies within the biblical exegesis process. I thank the Nazarene Theological College for providing a friendly and serious environment for conducting this research. I thank the University of Manchester for providing many helpful resources for this project. I thank the Corpus Linguistics department at Lancaster University for showing me the many ways corpora can be used to answer linguistic questions. I thank the Corpus Linguistics department at the University of Birmingham for the workshops toward analysing corpora data, and for the encouragement received toward analysing the Pauline letters as its own corpus. I thank the staff at Sketch Engine for hosting the corpora for this study and for helping me with technical difficulties. Fourthly, I thank the organisers of the conferences that allowed me to present papers related to this project, and fostered my own growth. These include the Eastern Great Lakes Biblical Society, the Stone-Campbell Journal Conference, The Midwest Region of the Society of Biblical Literature, The British New Testament Conference, the International Conference on Greek Linguistics, and the Post Graduate Research Seminars and One Day Theology Conferences at the Nazarene Theological College. Fifthly, I thank those who supervised this project and those who gave advice along the way. I thank Svetlana Khobnya for supervising this project and Dwight Swanson for co-supervising this project. I am indebted to their comments and critiques. ←xv | xvi→I thank David Lamb and Samuel Hildebrand for their critiques as well. I thank Geoffrey Horrocks for advice given on several occasions. Sixthly, I thank my thesis examiners, Todd Klutz and Dirk Jongkind, who found this project stimulating and compelling. I thank them for their questions, comments, and encouragement regarding publishing. Seventhly, I thank my wife, Aleyda Sedlacek for her support and encouragement throughout all phases of this project, including the years this was in development before the project was a reality. I am deeply indebted to her for being able to do this project. Eighthly, I thank friends and family who gave words of encouragement along the way. These include my two sons, James and Karl; my parents, Ron and Lois; my Pastor, Meredith Moser; my colleagues, Deborah Enos and Wayne Beaver; and great host of colleagues, friends, family members, and fellow students. Ninthly, I thank those who helped to build a friendship between the United States and the United Kingdom along with others maintaining that friendship, as this friendship between both countries provided me and countless others an opportunity to do research in the United Kingdom. Lastly and most importantly, I thank God for putting many events and people together which made all of these things possible.

Introduction

1. Introductory Remarks

The Greek synthetic Perfect tense-form1 is used 345 times and the Pluperfect is used only once in the Pauline corpus. But what does Paul convey and what should the reader understand whenever the author chooses a Perfect tense? To make these concerns more difficult to answer, the meaning of the Perfect tense is debated among not only biblical scholars for the Greek of the New Testament, but among Indo-Europeanists as well. Some of the debate centres around theoretical issues related to the nature of verbal aspect and categorisation of linguistic data. Other debate involves the application of verbal aspect theory itself to the Perfect tense-form specifically and consequently relating the observed uses of the Perfect onto that aspect. This problem is not unique to Ancient Greek, since the Perfect tense-forms of most languages have proven to be difficult to categorise within the verbal aspect network of their respective verbal system.

Greek has a long literary history, where the Perfect tense-forms are abundant in Greek literature in both their synthetic and periphrastic varieties. The ←1 | 2→synthetic form was highly productive in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods, and the periphrastic form is highly productive in the Modern Period.2 This abundance of both types of Perfect tense-forms makes the Greek language an excellent place in general to study the development of the Perfect tense-form and determine its verbal aspect. The identification of this verbal aspect enables a better understanding of Paul’s usage of the Perfect tense-form in his letters.

2. Linguistic Investigations into the Greek Language

A number of recent studies have emerged regarding the linguistic analysis of the Greek language. Several of these begin with the Greek textual data and then classify their findings in linguistic terms.3 They often seek answers from linguistics to explain some of the findings.4 Other studies begin with observable cross-linguistic phenomena and analyse the Greek text to see how that feature is exhibited in the Greek language, or whether it exists at all.5 Mostly, the studies on Greek verbal aspect fall into the second category but seek rationale for their linguistic observations among the writings of Ancient grammarians of Greek.6

3. Application of Linguistic Investigations to Exegesis

The purpose of applying linguistics to the Greek language in this project is to enable a better understanding of the use of the Greek Perfect tense-form in the ←2 | 3→New Testament generally, and particularly in Paul’s letters.7 Exegetes, pastors and other biblical scholars are dependent upon a careful study of the Greek language to accurately portray the message of the New Testament.8 The task of exegesis begins with the biblical text. Linguistics informs the linguistic interpretation of the text and is the background for a biblical interpretation of the text. Linguistics assists in understanding the previous Greek grammars and formation of new Greek grammars.9 Those who seek to better understand the text of the New Testament keep one foot in the grammars and the other in linguistic methods.10 Linguistic analyses of the Greek New Testament are a prerequisite to interpretation as they often provide more precision than the grammars. Linguistic analyses are independent of the grammars and working parallel to them, since they often inform in different ways than do grammars or lexica.

It is suggested that the scholar be critical of a number of factors regarding how linguistics relates to biblical studies. First, the scholar should be critical of how linguistics is informed as it relates to Greek. For example, linguistics should be informed by language data rather than by theory. Second, the scholar should be critical of how the grammars are informed for their structural categories and specific content.11 For example, distinctions created in linguistics should be reflected ←3 | 4→in the grammars. Where grammars leave linguistic distinctions vague, conflated, or missing, adjustments to the grammars are necessary. Thirdly, the scholar needs to be critical of theologically informed grammars, lexica, or grammatical tools, because they may reveal more regarding the theological bias of their authors, than they do to reveal the Greek language. Without a healthy set of criticisms in place, the tendency is for one to follow one’s favourite grammar or linguistic field to the exclusion of important evidence. Linguistics fits in the broader picture of exegesis as a component that precedes interpretation that is also independent from theological presuppositions.12

This thesis situates itself as a linguistic analysis of the Greek Perfect tense-form, while focusing upon the biblical text, and being informed by the historical usage of the Greek Perfect. This endeavour interacts with the biblical text to produce a linguistically informed understanding of Paul’s usage of the Greek Perfect tense-forms. The scope of this study is to connect linguistic description with grammatical observations, and to provide terminology to show compatibility between the two wherever helpful. One of the goals of this study is to provide a linguistically sound understanding of the Greek Perfect. Another goal is to gain a better understanding of how the Pauline corpus uses the Greek Perfect, and then to situate the Pauline usage of the Perfect within the history of Greek literature. A subsidiary aim of this research is to propose a new understanding of Perfects of the Indo-European language family more generally based on linguistic principles.

4. Thesis Statement

The Greek Synthetic Perfect tense-form, the one seen in the Pauline corpus and predominantly seen from the Classical Period through the Hellenistic Period, is shown in this treatment to have two verbal aspects in a complex array, having ←4 | 5→perfective aspect related to the action of the lexical core and imperfective aspect related to any state, whether resultant or otherwise.13 The Perfect tense-form can be used to emphasise either one of the two aspects, or both as the situation allows, depending upon whether the author has a state, event, or both in mind. This flexibility is shown to be in no violation of the uncancellability requirement.14 This treatment builds its case based on grammaticalisation studies,15 and supports its findings with diachronic analysis, morphology, theoretical linguistics, corpus methods, and cross-linguistic comparisons to ground its conclusions.16 This study connects the diachronic development of the Perfect along with the morphological analysis of its stem to a perfective aspect when referring to events. After examining the process of grammaticalisation for the reduplicant,17 this study connects the specific position of the Greek reduplicant along its grammaticalisation cline to an imperfective aspect that is then applied to states.18 The set of pragmatic functions exhibited by both the Classical and Post-classical synthetic Perfect tense-forms and the Modern periphrastic Perfect tense-forms are parallel to each other illustrating the complex verbal aspect apparent in both types of Perfect tense-forms. This analysis of both types of Perfect tense-forms shows compatibility between them aspectually. Thus, the aspect complexity of the periphrastic Perfect is a model for understanding that of the synthetic Perfect.

5. Chapter Organisation

This study consists of six chapters. The second chapter critically reviews linguistic works on verbal aspect and grammatical works on the Perfect tense-forms from several fields. This chapter establishes the status of scholarship regarding the verbal aspect of the Greek Perfect tense-forms and concludes that much confusion exists among the descriptions of the verbal aspect for the Greek Perfect tense-form. The need for clarification is highlighted along with a fresh analysis for the verbal aspect of the Greek Perfect. The clarifications of definitions for verbal aspect as a linguistic category and the components under that category are outlined. Elements from the literature that are useful for constructing a way forward are contrasted with problematic elements. The chapter concludes that verbal aspect is subjective, non-temporal, and morphologically expressed.

The third chapter provides a way forward beginning with an explanation of grammaticalisation. Next, insights from theoretical linguistics, structural linguistics, cross-linguistic analysis, and morphology are used to support grammaticalisation in constructing a new model for the Greek Perfect. The nature of stativity as a verbal aspect from the literature is challenged based on how stativity functions differently than perfective and imperfective, and then judges this difference based on the criteria of semantics established in the previous chapter. The useful components from the literature are combined with some new observations to build a fresh understanding of the verbal aspect of the Perfect tense-form. A morphological comparison of tense-forms shows that the internal vowel spelling of the productive pattern for the Greek Perfect mirrors that of the Aorist. This idea is shown to be compatible with what is suggested by grammaticalisation. This chapter constructs the complex aspect model for understanding the verbal aspect of the Greek Perfect tense-form. The argument is established that the Greek Perfect tense-form contains within its morphology two aspects that remain in tension with each other, based on its morphology and diachronic development, and supported by analysis of adverb collocations. Reduplication studies support the claims made here.

The fourth chapter analyses the Pauline corpus. Various linguistic environments for the Perfect tense-forms of the Pauline corpus are included and analysed. This chapter examines stative contexts, eventive contexts, and contexts that have both components. The special case of οἶδα and the Perfect of communication lexemes found in citation and referential contexts are treated separately. Compatibility between the Pauline corpus and the complex aspect developed for ←6 | 7→the Perfect in the previous chapter is shown in the discussion of the verbal aspect of the Perfect tense-forms following the selected examples.

The fifth chapter introduces corpus linguistics as a tool to build data for analysis. The Pauline corpus and a larger diachronic epistolary and moral literature corpus spanning roughly eight centuries are both defined along with their uses. The Pauline corpus is the primary text analysed, while the diachronic corpus is a test corpus that is used to confirm the findings within the Pauline corpus, and provide balance to the general conclusions. The discussion of the data drawn from the two corpora shows that Paul’s usage of the Greek Perfect is compatible aspectually with the other Greek letter writers and moralists. The unique usages of the Greek Perfect with the Pauline corpus are highlighted as well. The Pauline corpus contains more Perfect tense-forms inside supplemental clauses and employs a wider variety of eventive lexemes in this role than do the other writers examined. The compatibility between the complex aspect explained and supported in the third chapter and the observations in the Pauline corpus in the fourth chapter are highlighted in this chapter as well. The analysis corpus also shows examples of stative and eventive Perfect use, both long before and well after the New Testament period, further supporting the claim that the aspect of the Perfect is complex generally.

The sixth chapter draws the conclusion that the Perfect has a complex aspect, perfective for any action and imperfective for any state. Although these states primarily are states of the grammatical subject, whenever the state is relevant for the object, it will be imperfective also. This chapter articulates the contributions to linguistics, Greek grammatical discussions, and biblical studies. Next, the limitations of the size and scope of the test corpus are described. It closes by suggesting further research through expanding the test corpus and comparing all the tense-forms, and not only the Perfect tense-forms.

Overview of Verbal Aspect Studies as Related to the Greek Perfect and Pluperfect Tense-Forms

1. Introductory Remarks

The definition of verbal aspect as a linguistic category belonging to the larger category of semantics is of first importance, making sure that the definition fits the criteria derived from semantics. This is required before the verbal aspect of the Perfect tense-form can be analysed. Secondly, the members which make up the set of items called verbal aspects require definition, while ensuring that those members satisfy the criteria for verbal aspect and its larger category, semantics. The definitions of verbal aspect prominent in the literature include a view on an “internal temporal constituency” of a given situation,1 and an author’s “point-of-view” on a situation.2 Both of these can be and sometimes have been misunderstood. When verbal aspect is understood as an internal temporal property, rather than a view on that property, this allows for confusion between aspect and temporal matters. The features relevant to time are better understood as the effect aspect has on time, rather than informing the definition for aspect. The view is ←9 | 10→primary. Understanding verbal aspect as a point-of-view from which an author views a situation leads problematically to seemingly endless possibilities for the points that can be described.3 A view on a situation is primary rather than the point from which it is viewed. Further clarification is required in the definition of verbal aspect.

Not only does variety exist in the descriptions of verbal aspect as a semantic category, but in the descriptions of a specific verbal aspect for the Perfect tense-form as well. Some studies describe the semantics of the Perfect utilising verbal aspect, while others focus on some of the functions of the various tense-forms or on some of the practical applications of Perfect tense-forms more broadly.4 Attempts to define the semantics of the Perfect range from being truly semantic to being somewhat temporal or functional.5 One semantic description for the Perfect is “perfective,” equating the aspect of the Perfect with that of the Aorist due to its actional component. Another semantic description is “imperfective,” equating the Perfect with the Present and the Pluperfect with the Imperfect, due to the ongoing nature observed for the Present. A third type of aspect described in the literature is “stative,” where the state of the grammatical subject is highlighted by the Perfect tense-form. Other descriptions combine features of tense ←10 | 11→or Aktionsart into their understanding of the Greek Perfect and mix functional or contextual material with the semantics.6

One problem in the above descriptions is that perfective and imperfective are opposites within the verbal aspect descriptions, raising the concern regarding how both could be possible. Since each aspect is selected for the whole tense-form by different scholars it is unclear how this decision is related to the morphology of the Perfect tense-form. Another problem is how stativity fits within a verbal aspect network, where complete (perfective) and incomplete (imperfective) views on the verb are items of the same set, while stativity seems to belong to a different linguistic category than do the perfective and imperfective. A third problem is how temporal descriptions relate to aspectual ones. A fourth problem is that for those whose definitions blend aspectual and pragmatic components, they obscure what verbal aspect is itself. Before these issues can be sorted out, it is helpful to review what verbal aspect is as a semantic category, and how this category fits into the overall meaning of verbs generally, and then to review more specifically what the verbal aspect is for the Perfect tense-form. Varieties in the descriptions of the Greek synthetic Perfect tense-form appear to be partly due to differences in how verbal aspect is understood.

2. The Development of Verbal Aspect as a Term for Grammatical Analysis

The analysis of verbal aspect as a category places boundaries on what items can be included as individual verbal aspects. Several scholars have distinguished verbal aspect as a category separate from tense, mood, lexical meaning, and Aktionsart. Concepts such as the subjectivity of aspect and uncancellability of semantics more generally emerge as components of this discussion, and are defined in this section. These definitions lead to refinements in the definition of the category of verbal aspect.

2.1. Situating Verbal Aspect within Linguistics

Before analysing verbal aspect as a verbal category, it is necessary to situate verbal aspect as a linguistic concept in its context. Verbal aspect is primarily a semantic category. Semantics involves the meaning of a particular form or lexeme before ←11 | 12→it is contextualised. Semantics is divided into two portions. Formal semantics is related to meanings associated with forms of words, while lexical semantics is related to word definition. Since the present study is focused on verbal aspect, and thus formal semantics, the semantics of the form is most important, while lexical semantics will be mentioned only where helpful to avoid confusion. Porter defines “verbal aspect” as a component of semantics and related to the meaning of the verb form rather than to its function.7

Pragmatics is different from semantics in that it involves how a particular form or lexeme is used in certain contexts. Pragmatics also involves two components. First, the meaning of a particular word or form that arises because of a particular contextual setting is one element belonging to pragmatics. Olsen calls these “implicatures.”8 Second, pragmatics explains how a word might be used in one way or another to create a different effect. In this way, pragmatics includes functions of a word or a form. Each verb’s relationship with various contexts produces the various pragmatic functions for that verb. A meaning associated with pragmatics is not durable apart from its context in contrast to one from semantics. As related to form, semantics refers to the core meaning of a grammatical form that is uncancellable by context, while pragmatics refers to the ways a grammatical form is used in context, and any meaning derived from this special use is cancellable by changing the context.9 These pragmatic “meanings,” “functions,” or “uses” can be cancelled by changing the context, but in contrast to this, semantic “meanings” cannot be cancelled this way. This study avoids elements that rely on “use” or “function” to describe the verbal aspect of the Perfect because to do so would conflate semantics with pragmatics. The distinction between semantics and pragmatics will be maintained throughout this project. Figure 1 places the linguistic elements under their respective category.

This project is concerned with semantics as it analyses the verbal aspect of the Perfect. It is also concerned with the pragmatics of the Perfect where certain uses of the Perfect potentially confuse the research on aspect, and to show how its verbal aspect functions in these special circumstances. Keeping both elements separate is of importance along with developing and maintaining clear definitions of verbal aspect and Aktionsart as will be developed later.

←12 | 13→Olsen provides some detail for when a semantic item is uncancellable. A semantic meaning cannot be cancelled without a contradiction occurring or reinforced without apparent redundancy.10 When deciding whether or not a meaning is cancellable, it is helpful to apply a test to see whether a meaning is cancellable. Olsen provides a text for a lexical situation. For example, she supplies a basic sentence, “Elsie plodded down the walk.” Since adding “slowly” or “not slowly” to the sentence runs into either contradiction or redundancy, slowly is a semantic meaning for the word “plodded.” Also, since the concept of slowness cannot be cancelled for “plod,” then the idea of “slowness” is semantic for the word “plod.” On the other hand, adding the ideas of “tired” or “not tired” to the sentence produces sentences with meaning either way. Therefore, the idea of “tiredness” is a pragmatic implicature of the word “plod,” rather than a semantic meaning for the word, because it is cancellable.11 A person can be said to plod even if he or she is not tired. Although this is an example of “uncancellability” vs. “cancellability” within lexical semantics, when this same test is applied to semantics of a verbal form with similar results, the same division between semantics and pragmatics applies. The semantic components cannot be cancelled, while pragmatic ones can. Verbal aspect for the Perfect, if it is correctly identified, is likewise uncancellable by adding context. The goal in this study is to find a description for the verbal aspect of the Perfect tense-form that is not cancelled by context, so that it satisfies the semantic requirement for verbal aspect.

2.2. Related Semantic Concepts

Several semantic concepts directing the understanding of verbal aspect are developed over the next few sections. The subjectivity component distinguishes between elements that focus on the author’s perspective, and those that focus objectively on the nature of the real situation. The subjectivity criterion is a test that must be met if something is considered a property of verbal aspect. The non-temporality of aspect is another important aspectual concept. It helps in keeping temporal ideas about the verb system separate from aspectual ideas. A tendency exists to conflate aspectual and temporal properties if one does not carefully separate them when discussing verbal aspect. Morphology of the Greek verb is a third important concept related to verbal aspect. The verb form encodes various meanings for the verb system in its morphemes; therefore, verbal aspect should be apparent in the morphology of the verb.

2.2.1. The Subjectivity Criterion

Within the realm of semantics, verbal aspect is defined as the authorial subjective viewpoint regarding a verb’s action or state.12 It is not the objective quality about any activity or situation.13 The subjectivity criterion for verbal aspect was developed to oppose Aktionsart, which is an objective category. Lexical aspect, related to Aktionsart and often confused with verbal aspect, entails an objective portrayal of an action or state.14 Phrases such as “this verb type refers to sudden activity” are an example of Aktionsart. Objective categories of language report on the actual situation referred to, including the type of action, while subjective categories report on how the speaker or author perceives the situation and portrays it, regardless of how the actual situation occurred.15 Subjectivity also implies that the author has a choice in how to portray a situation. Aspect reports an action as either complete or incomplete in the perspective of the author, while Aktionsart reports on how the real situation unfolded, with a range of options available for describing different situations.16 Another way of thinking how aspect relates to the action is that the author reports on the action as either whole or partial by using different verbal aspects.

←14 | 15→Debate exists whether any of these categories is fully subjective or objective, but these categories still oppose each other and are distinct from each other in the matter of subjectivity and objectivity.17 Although the debate is too large for a full treatment here, a few key points are necessary to establish the direction of this argument. Porter categorises aspect as fully subjective and Aktionsart as fully objective.18 Fanning cautions against assigning too much subjectivity as the range of aspectual choices are often limited by context, and against assigning too much objectivity to Aktionsart, a lexical category, because the perspective of an author on an action does not always correspond to reality.19 Another concern is that a speaker might not always have a choice of which aspect to use. This means that in some situations aspectual distinctiveness could be non-apparent. This choice may not be available or practical to the author or speaker for every situation, but in defining verbal aspect, this subjective choice stands in contrast to the objective nature of the situation itself. When a choice exists between aspectual forms, some effect will be noticed between the use of one tense-form or the other, and that difference in effect is related to aspect. The author chooses the tense-form based on how he or she wants to portray a situation that he or she reports to a reader. Fanning sees that the selection of any aspect may be limited for certain situations the author wishes to portray, but the speaker must choose one from the available choices.20 This subjective authorial selection of a verb form is made sometimes to avoid implications of another aspect inherent in a different verb form of the same lexeme.21

The aspect that the author chooses is often the cause for a number of functional categories. One of these specialised functions belonging to pragmatics could also be a reason an author might choose one form over another. If the author were to choose a special function of a tense-form as the main reason for its selection, the author will use the aspect that is associated with that tense-form, and will not have as much freedom to select an aspect. Even taking Fanning’s concerns into consideration, verbal aspect still has more subjectivity than Aktionsart in Fanning’s own analysis. Campbell maintains that Aktionsart is primarily an objective category while aspect is primarily a subjective one.22 Although various ←15 | 16→scholars see different degrees of objectivity and subjectivity at work, the vast majority recognise this distinction and make allowances that neither element is either totally subjective or totally objective, but that aspect is more or less subjective and Aktionsart is more or less objective.

For the analysis of verbal aspect in this book, verbal aspect is considered a distinctively and generally subjective category when compared with Aktionsart. This distinction between subjective and objective components will be sufficient to filter items from the set of linguistic terms placed into the verbal aspect category. If an item is considered a verbal aspect, yet is not subjective, then that item is rejected from the category of verbal aspect in this study. However, it will not necessarily be automatically included in the category Aktionsart, if it is rejected from the category of verbal aspect. Not everything rejected as an aspect belongs in the Aktionsart category.

2.2.2. Non-Temporal Basis

Although a full treatment on tense is not developed in this thesis, a discussion about how aspect is related to time is necessary to sort out the conflation in the literature. Verbal aspect is a category distinct from tense, yet, somehow related to time.23 Tense refers in some way to temporal reference, which can be of several types. Absolute temporal reference points to a specific time such as the past, the present, or the future.24 Relative time works differently and places one item as belonging either before, at the same time as, or after another item, but both items could be in the past, in the present, or in the future.25 Both items referred to under relative time might also belong to two different absolute reference times. When relative time is understood instead of absolute time, both items are related to each other instead of related to a present moment or a moment chosen by the speaker. The relationship of verbal aspect to time is different than either a reference to absolute time or to relative time. Aspect is somehow related to time yet does not refer to time itself, or any specific temporal location.26 Fanning points out that verbal aspect produces temporal meanings, which are related to the internal action of the verb and not to deictic reference or tense.27 From this it seems that for any temporal properties relevant to aspect, they are secondary to aspect and dependent upon it.

←16 | 17→Tense is more complex than just absolute time or relative time. Klein develops temporal properties further. Whenever a speaker speaks, he or she creates something called the topic time.28 This topic time might be the present moment, or it could be any moment the speaker chooses. Usually if the speaker does not specify a topic time, then the present speech moment is understood to be that topic time. The topic time could be a point in time, but it does not have to be a point. It also could be a specified duration of time. Once the topic time is established by the speaker, the events mentioned by the speaker will be located in reference to that topic time.29 Each event will be given its own event time. Deictic temporal references, such as past, present, and future, relate the event time of each event to the past, present, or future of that topic time. Olsen maintains that verbal aspect relates the event time to the reference time, while tense relates a reference time to a topic time which may be the speech time, or some other time indicated by the speaker.30 Dahl develops nearly the same idea. Dahl defines aspect as “a type of relation between reference time and event time,” and defines tense as “a type of relation between reference time and local evaluation time,” or deictic centre.31 He defines the perfective aspect as the event time being included in the reference time.32 Basically, a perfective aspect has a reference time that includes all of the event time, while an imperfective aspect has a reference time that is less than the whole event time and places the reference time somewhere within the event time.33 Another way to discuss this phenomena is to understand that the perfective views the endpoints of the action, while the imperfective does not. Sasse uses this approach after separating out a type of boundedness for aspect away from the types associated with Aktionsarten.34 Typically “boundedness” refers to the Aktionsart value of telicity, but since Sasse defines three types of boundedness, his third definition works for aspect properties. Bary uses Formal Semantics to ←17 | 18→show how Klein’s thesis, relating aspect to time, works for Greek Aorists and Imperfects.35

Dahl defines “aspect” as a “speaker’s perspective on the internal temporal structure of a situation.”36 This is similar to Comrie’s definition of verbal aspect, where the internal time of the action is in the speaker’s view.37 This means that each verbal aspect has a different view of the internal time of the action. This seems quite compatible with the ideas of Olsen and is similar to Fanning’s statements regarding aspect.38 A potential problem occurs whenever aspect is equated with the amount of time in view, thus conflating temporal properties with aspect. One way to keep them separate is to keep verbal aspect as the subjective perspective of the author, while leaving the internal temporal components as the objective components of what is in view when an author has a certain perspective. Using the endpoints explanation per Sasse, the perfective view on the activity is the verbal aspect, while the endpoints being in view is part of the objective character of the verb and more related to the internal time of the action. Although a strong relationship exists between the view on the internal time and the internal time itself, these need to remain separate in order to construct adequate tests for determining whether or not an item should be considered a member of the verbal aspect category.

2.2.3. Encoded by the Verb Form

The location of verbal aspect within the morphology of the verb is discussed next in order to connect verb forms to their respective aspects. The idea that verbal aspect is connected somehow to the morphology of the verb suggests that morphological concerns should shape the analysis of the Perfect. The viewpoint on the action or state described earlier, or the manner of viewing the action or state is morphologically expressed in the stem choice of the tense-form and is the primary meaning for that tense-form in all modes. The morphology of the verb contains the components for its verbal aspect. The connection between morphology and verbal aspect is sometimes ignored or left undeveloped by the theorists, but is a key component in this research. Aspects are not detected only through ←18 | 19→contextual considerations,39 but are denoted by certain elements in the stem of the verb.40 Since the stem of the verb is the locus for verbal aspect, then the verbal aspect is not connected to the augment, or the primary and secondary endings, but something integral to the stem. This stem also cannot include the lexeme itself, since this provides the lexical aspect. The augment, endings, and lexical affixes need to be removed from the stem first in order to analyse this. The remaining difference between the tense-forms, once these morphemes are removed, is usually that of the internal stem vowel spelling, and this difference is most noticeable between the Present and the Aorist stems.41 Therefore, this study is concerned with the differences in stem spellings where they are evident to determine aspectual affinities. Problematically, few studies in the available literature demonstrate how their respective decisions regarding verbal aspect are derived from the morphology of the Greek verb. This study will connect verbal aspect to explicit morphemes within the Greek Perfect tense-form.

2.3. Situation of Verbal Aspect among Other Elements Called “Aspect”

Several linguistic elements other than verbal aspect have been called “aspect,” including lexical aspect, Aktionsart, and phasal aspect or aspectualisers. Early in the literature, these were often conflated with verbal aspect, but now have been defined as separate entities. These will be each described, followed by a statement of how this study will distinguish between their terminology and that for verbal aspect in light of the separation of these concepts.

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 432

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433195747

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433195754

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433195730

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19512

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (September)

- Keywords

- Verbal Aspect Perfect Tense-form Grammaticalisation Linguistics Corpus Linguistics Perfective Imperfective Stative Morphology James E. Sedlacek The Verbal Aspect Integral to the Perfect and Pluperfect Tense-Forms in the Pauline Corpus A Semantic and Pragmatic Analysis Studies in Biblical Greek

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2022. XVIII, 432 pp., 35 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG