Learning from Resilience Strategies in Tanzania

An outlook of International Development Challenges

Summary

The current Covid situation has shaken the whole world and raised many questions on how the different regions and countries could adapt and develop resilience strategies in an uncertain and ever-changing context. Therefore, the book is not only about Tanzania but also about what we can learn from the research on Tanzania in terms of vulnerabilities and resilience strategies. This book is an outlook of International Development Challenges.

This book is co-funded by the European Union in the framework of the project Pilot 4 Research and Dialogue.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Introduction Chapter (Pascaline Gaborit PhD)

- Background Chapter: The Vulnerability and Resilience of the Economy in Tanzania: A Historical Context (Donath Olomi PhD)

- Part I: Socio-economic Realities and Impacts

- Chapter 1: Informal Workers in Tanzania: Coping Strategies and Resilience Factors (William Amos Pallangyo)

- Chapter 2: The Socio-economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women and Girls in Tanzania (Kaihula Bishagazi PhD)

- Chapter 3: Tanzania’s Livestock Sector: Resilience and Potentials (Wambura Messo and Felix Adamu Nandonde, PhD)

- Part II: Resilience to Global Challenges and to Climate Change

- Chapter 4: Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) and Local Supply Chains: Prospects on Poverty Reduction, Trust and Sustainability (Felix Adamu Nandonde, PhD and Pascaline Gaborit PhD)

- Chapter 5: Vulnerabilities and Resilience to Climate Change in Tanzania (Pascaline Gaborit PhD)

- Chapter 6: Forests’ Management and Protection in Tanzania: Challenges and Reality (Prof. Magreth S. Bushesha and Pascaline Gaborit PhD)

- Chapter 7: An Account on the Resilience of Tanzania’s Private Sector (Ali Mjella and Hans Determeyer)

- Chapter 8: Civic Participation and Water Governance in the Kiroka Village of Tanzania (Saida S. Fundi PhD)

- Chapter 9: Conflict Prevention, Dialogue and Resilience: Exploring Links and Synergies (Prof. Élise Féron PhD and Cæcilie Svop Jensen)

- Part III: The Role of Women between Vulnerability and Resilience

- Chapter 10: From Women to Gender and Intersectionality: Rethinking Approaches to Economic Vulnerability and Resilience (Prof. Élise Féron PhD (Tampere Peace Research Institute))

- Chapter 11: Minority Participation of Women in Economic Sectors in Tanzania: Is It a New Norm? (Theophil Michael Sule)

- Chapter 12: Women in the Informal Sector in Tanzania: The Case of Dar Es Salaam City (Constantine George, Cornel Joseph PhD and Colman T. Msoka PhD)

- Epilogue and Short Conclusion

- Biographies

- Contributions and Acknowledgements

Introduction Chapter

Pascaline Gaborit PhD

“There is hope in every African village” Bertrand Ginet Co-Founder Pilot4dev

This chapter is the introduction from a multi-faceted collective book, gathering multi-disciplinary research and analysis of several researchers. It approaches the different resilience strategies in Tanzania, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic This collective research considers theoretical concepts such as resilience, gender equality, conflicts prevention and climate change.

Tanzania has been considered a model for development, peace and stability despite the arrival of refugees from neighbouring countries, and the potential tensions linked to the economy or to climate change. Although it has accessed the rank of Middle-Income Country, the country is at a crossroad still facing several challenges. The needs remain important in terms of health facilities, water, sanitation, climate adaptation, the development of civil society and poverty alleviation. At least 26.4 % of the population still lives in poverty1. An important part of the population works in the informal sector in both urban and rural areas. The relations between the private sector and the public government have been stormy, while analysis on women’s resilience strategies, climate adaptation, conflict prevention, multinationals/supply chains, or on the informal sector offer vastly different angles of approach. In 2020, the COVID pandemic has come as a shock worldwide, and has raised many questions on how the different regions and countries could adapt and develop resilience strategies in an unpredictable context. This collective book is not only about Tanzania, but about what we can learn from resilience strategies in Tanzania. It provides in alternance chapters based on empirical field studies and more theoretical chapters.

This introduction chapter first approaches resilience as a multi-disciplinary concept explaining why Tanzania is of particular interest in terms of research on resilience strategies (1). Then, a general description of the country is provided addressing the transformation needs of the country ←11 | 12→and the shock created by the COVID pandemic (2). Finally, this introduction chapter will present the objectives of this research book (3), its methodology as well as its structure and content.

1. Resilience as a Multi-disciplinary Concept

Resilience is a cross-disciplinary concept referring to the ability to cope, recover and build back from stress, shocks, and crisis. Originated from the world of physics and sciences where it merely meant “bounce back”, it has been eventually applied to psychology, and has since then been widely used in other areas such as disaster management. Its use as a concept in policy discourse has been exponential since the 2000s (Brassett et al., 2013; Brinkmann et al., 2017). The soaring use of the concept of resilience in policies can be interpreted as a progressive acceptance that “sustainability” will not be an easy path, and that societies, economies, cities, organizations still need to cope with disruptions. In that sense, resilience is associated to a decrease in the faith towards continuous progress, especially in the areas of climate related disasters, economy, stability and development.

In the field of economics, the concept of resilience presents the advantage of considering the ability to recover from severe crises linked to exogenous factors, and to minimize the risks of recession (Hallegate, 2014). Economic resilience has been iconized by the country of Singapore which has been able to resist to the 2008 economic crisis, despite its remarkably high economic and territorial interdependence. This has been called the ‘Singapore paradox’ (Briguglio et al., 2008). In a Research paper dated from 2008 (Briguglio et al., 2008), the United Nations University explicitly links the concept of Resilience to Vulnerability. The authors of the paper define economic vulnerability as ‘the exposure of an economy to exogeneous shocks, arising out economic openness, while economic resilience is defined as the policy-induced ability of an economy to withstand or recover from such shocks’ (Briguglio et al., 2008). This definition links economic resilience to four broad areas identified as main factors-namely macroeconomic stability, microeconomic market efficiency, good governance and social development. In the present book, we will not restrict the concept of resilience to its economic application. The research will embrace different aspects and areas such as socio-economic development and realities (Part I), the adaptation to climate change and other global challenges (Part II) and the role of women (Part III). We will therefore ←12 | 13→consider the broader definition: Resilience as a cross-disciplinary concept referring to the ability to cope, recover and build back from stress, shocks, and crises.

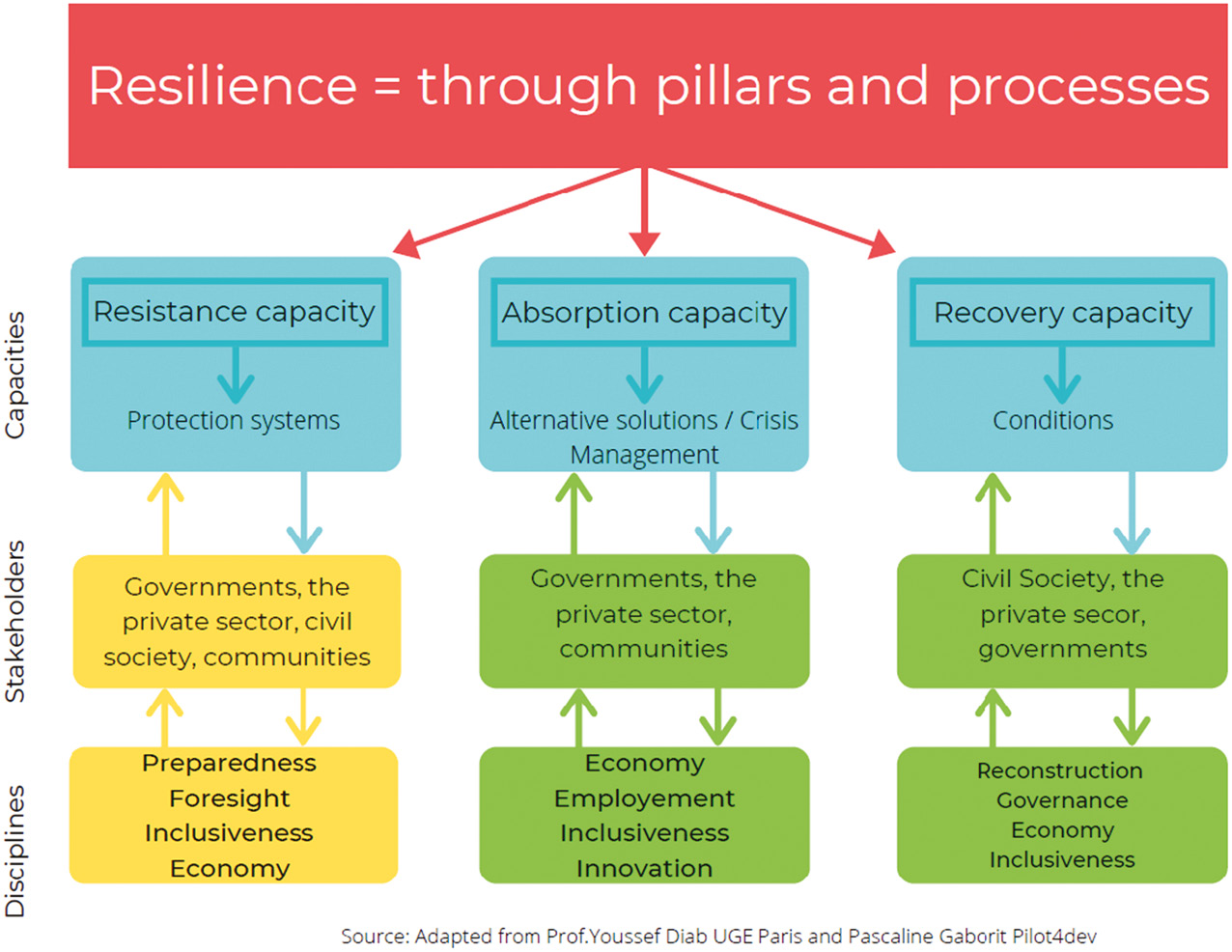

Fig. 1:Resilience through pillars and processes (Adapted from Youssef Diab EIVP team 2020, Pascaline Gaborit Pilot4Dev.)

The concept of resilience however comes along with strong limitations: its undifferentiated use may transform it into a new ‘buzz word’, emptied of its substance (Brinkmann et al., 2017). For some authors it would be inherently “messy” in its application (Harris et al., 2017). Its misuse would come with a “negative side” such as the one to underestimate the impacts of damages and disasters (Mahdiani, 2020). For instance, in a context of pandemic, post-disasters or post-terror attacks, focusing on resilience can be in contradiction with grief and support to the victims. ‘Resilience seems to carry a productive ambiguity that both resists exact definition and allows for a spectrum of interactions and engagements between policy and the everyday which are as (seemingly) effective as they are (apparently) apolitical’ (Brassett et al., 2013, p. 221). ←13 | 14→The concept also has been criticized as addressing both a process and an outcome, or as ignoring the questions of power and justice (Harris et al., 2017, Chapter Féron).

Indeed, a focus on resilience related to the anticipation of risks in policies or in practice may bring losers and winners as resilience actions can be performed at the expense of some groups or stakeholders. Some authors such as Ziervogel et al. (2017) also highlight the fact that ‘the level of acceptable risk’ can very much vary from one group to another, as can the level of exposure to the risk. This raises governance questions – who determines the acceptable levels of risks? Under what ground? Who benefits from resilience actions or policies’ operationalisation? The Covid-19 crisis has quite synthetized such dilemmas in many countries, on whether the health, the economy’s vulnerability, or the population wellbeing and freedoms should be prioritized as the most resilient response.

Even more of a concern – practitioners in the areas of development and humanitarian aid sometimes see this concept as a real threat. The tagline ‘Only the strong survive’ could sooner or later be replaced by ‘Only the resilient survive’ in the practice of disaster management and humanitarian aid. In the sector of security, people (as opposed to groups, states of communities) could be increasingly considered as responsible for developing a response (Brassett et al., 2013). The use of the term – in an international context in particular – can induce an ideology ‘affirming the responsibility of non-Western societies for their own threats and insecurities, whether from conflict, poverty or environmental devastation’ (Chandler, 2013, p. 279). It also raises subsequent related questions – what is the contrary of resilience: is it destruction? (…) What are the indicators for a possible assessment?

The complexity of the concept and its application should however not dismiss or disqualify the use of resilience as a concept. Its appropriate use can bring strength to risk management practices in an uncertain or unpredictable context. This means that advocating resilience should be well-thought and embed complexity. For example, policy and development programs with a focus on resilience should not replace prevention and assistance to vulnerable groups. Disasters resilient infrastructure should add up to and not replace early warning systems. We should not exclude what we could call a “Titanic Syndrome” or a vicious circle by which a focus on resilience would overshadow the necessity of any ←14 | 15→emergency response. Indeed, resilience should not mean less emphasis on the anticipation of risks.

We suggest several precautions and clarifications for the concept to be used: the fact that resilience can be applied as a system trait, as a process and as an outcome (Brassett et al., 2013), the growing emphasis on measuring resilience (Moser et al., 2019), the importance of resilience strategies in dealing with uncertainty or unpredictability, the necessity to address multiple and diverse interests and the integration of the risks’ anticipation in the analysis.

The UN Sendai Disaster Framework, adopted in 2015, is equally interesting to overcome all these questions, as it proposes a multiple-steps approach: prevention, preparedness, early warning, recovery and reconstruction. Although this Framework does not apply literally to all areas – like economic shocks – it has the advantage of countering possible misinterpretations. Authors such as Harris et al. (2017), have equally suggested the concept of “negotiated resilience” to address the concept in its complexity. They define it as a process that requires engagement with diverse actors and interests, and which will inevitably lead to possible diverse options and trade-offs. This concept of “negotiated resilience” is particularly interesting in the socio-economic area, as the economy entails many choices, options and reliance on macroeconomic policies. In contrast, the concept of “social-ecological” resilience defined by Beichler (2014) also presents the advantage of addressing the environmental and social issues but may be less relevant in a context of economic crisis or disasters’ management.

|

Resilience | ||

|

Possible uses |

Disaster management including pandemics or floods, climate adaptation, economic shocks, external shocks including conflicts or emergency situations. | |

|

Critics |

Buzzword, covering both a process, a trait or an outcome, approach putting the responsibility on the impacted groups, may lead to a confidence excess and a decrease of risk anticipation (Titanic syndrome), may serve the interest of some groups and ignore the questions of power and justice. | |

|

Induced by the use of the term |

Importance of the concept to deal with uncertainty, shift from understanding resilience to active resilience building, growing emphasis on transformation/changes, and on measuring resilience. | |

|

Orientations |

Details

- Pages

- 380

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9782875744333

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9782875744340

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9782875744326

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18824

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (November)

- Published

- Bruxelles, Berlin, Bern, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2022. 380 pp., 15 fig. col., 9 fig. b/w, 20 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG