The Agency of Art Objects in Northern Europe, 1380–1520

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- I. Introduction

- I.1. From Kunstgeschichte als Geistesgeschichte to a posthumanist theory of the agency of things

- I.2. The illusion of the objectivity of the work of art

- I.3. Multisensory reception of the work of art

- II. Objects in Space: The Mobility of the Beholder

- II.1.Objects suspended in space

- II.2. Giants, colossuses, monuments

- II.3.Large-scale altarpieces

- III. Animated Things: Manipulation and Handling

- III.1. Precious small objects

- III.1.1. Small books

- III.1.2. Precious metalwork

- III.1.3. Devotional beads and nuts

- III.1.4. Small paintings and micro-altarpieces

- III.1.5. Painted panels as jigsaws, playing cards, and cards to assemble

- III.2. Moveable objects: open and closed, folded and unfolded, assembled and disassembled

- III.2.1. Diptychs – manual operations

- III.2.2. Polyptychs – staging the interior and exterior, and manipulating the direction of the figures’ gazes

- III.2.3. Tapestries: folded and unfolded

- III.2.4. Veiling and wrapping

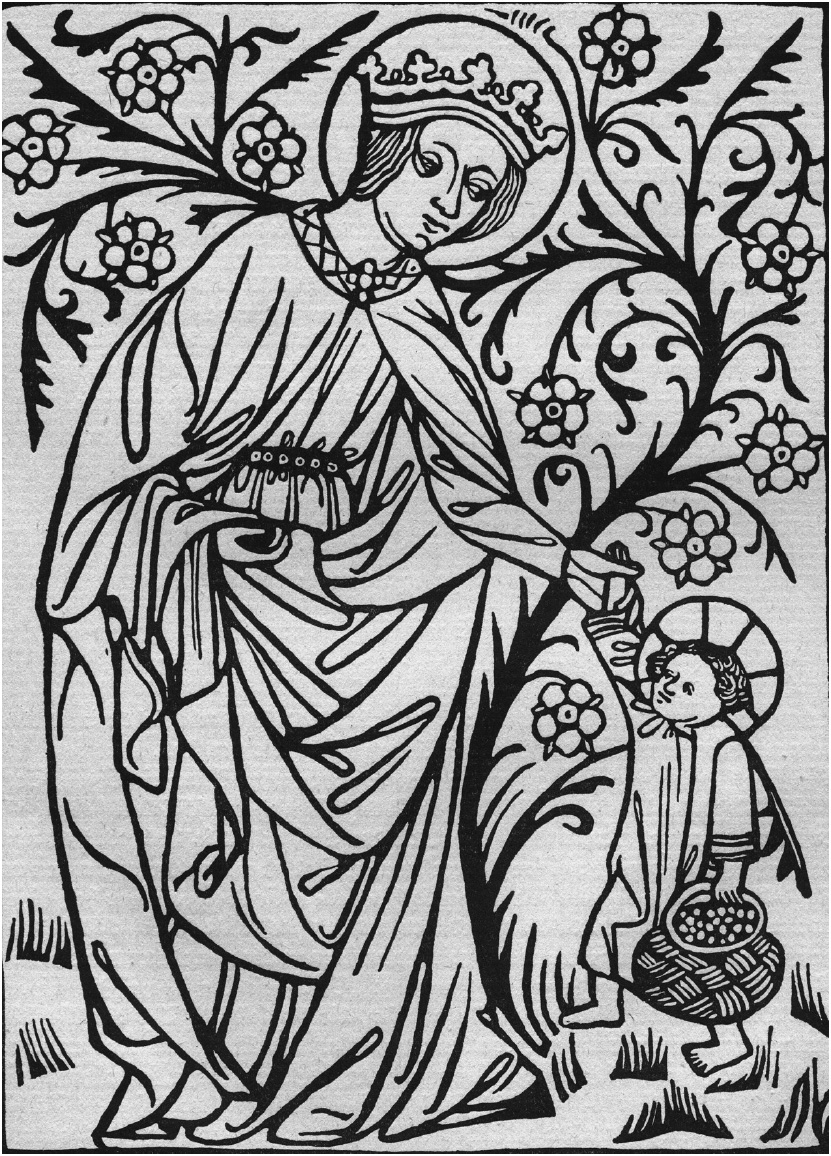

- III.2.5. Prints on the move: Einblattgraphik and print series

- III.2.6. Moveable and animated statues

- III.2.6.1. Shrine Madonnas

- III.2.6.2. Statuettes of the Christ Child: figures to be clothed

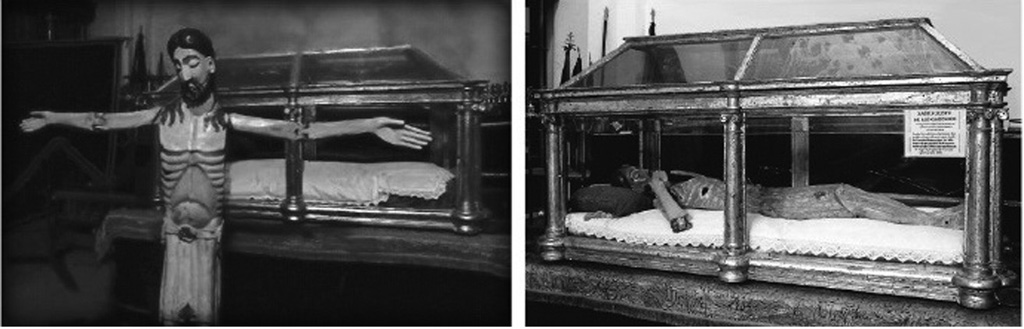

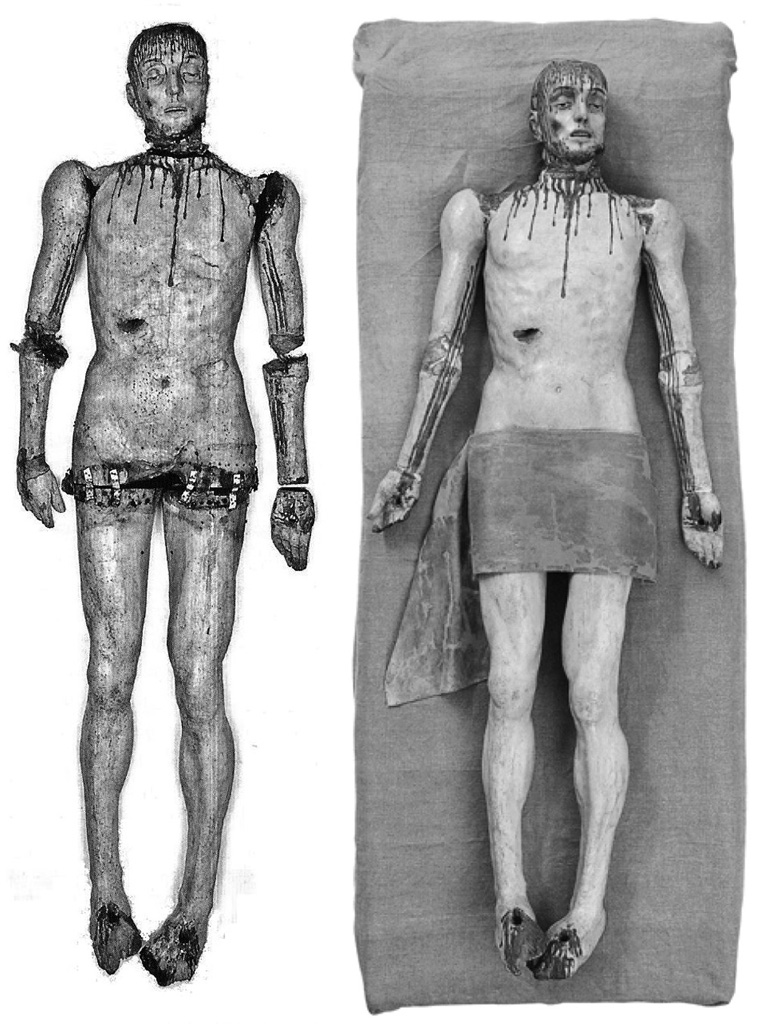

- III.2.6.3. Animated and moveable figures of the Crucified and Resurrected Christ: rituals of Depositio, Elevatio and Ascensio

- III.2.6.4. Palmesel and the Palm Sunday procession

- III.2.6.5. Other mobile figures

- III.2.7. Mechanisms, automata, clocks and apparatus

- III.3. Scale of the object and the technology of production

- III.4. Legible and illegible: looking at paintings through a magnifying glass

- IV. Words and Texts in Art: The Culture of Reading in Paintings

- IV.1. Reading paintings and viewing books: culture of prayer books and of chronicles

- IV.2. Inscriptions and texts in paintings: words as artworks

- IV.3. Empty banderols: reading the unwritten

- IV.4. Texts and inscriptions in Hebrew

- IV.5. Text-Image Panels – paintings to be read

- IV.6. The direction of reading and viewing

- V. Time and the Narrative in Paintings

- V.1. The natural, calendar, liturgical and historic time

- V.2. Time in medieval philosophy and theology

- V.3. Long story – continuous space: the episodic, simultaneous, segmented and disrupted narrative

- VI. Meditative Spaces: Great and Small Pilgrimages

- VI.1. Travel – journey – pilgrimage

- VI.2. Pilgrimages

- VI.3. Real and virtual pilgrimages

- VI.4. Pilgrimages to the Holy Land

- VI.5. Mental pilgrimages and the visual aids

- VI.6. Reconstructions of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the Via Crucis

- VI.7. Images from the Lives of Christ and the Virgin in the context of spiritual pilgrimage

- VI.8. Paintings as panoramas of pilgrimage sites

- VII. The Agency of Things and Humans – Final Remarks

- Selected bibliography

- List of Illustrations with Photo Credits

- Index of Historic Persons

I. INTRODUCTION

This book is the outcome of my research on the Burgundian and Netherlandish art of the fifteenth century. Hitherto, I have published my studies in Polish in three volumes entitled: The Art of the Burgundy and the Netherlands 1380–1500.1 The present book is an expanded and revised version of selected chapters from the third volume of this trilogy, The Community of Things: The Netherlandish and Northern European Art 1380–1520, which was published in 2015.

I investigate the art as a set of man-made objects, which can take control over humans. They are active, because they dictate the cognitive perspective, the modes of visual perception and experience of space and scale. These objects can also stimulate certain behaviours. They can force specific movements, gestures, actions, and manipulations, animating a thing meant to activate the beholder’s own body. The definitions of space and scale, animation, mobility and manipulation are vital modes for the agency of works of art in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

In a way, my approach is informed by the latest shift in both art historical and general historical studies. To the present day, such methodology remains the final stage in the line of different concepts about history of art, from the history of spirituality and mentality, iconology, through semiology, structuralism, the Marxist social history of art, hermeneutics, phenomenology, post-modern theories of post-structuralism and gender studies, to the recent posthumanist thought. This last theoretical strand – still in statu nascendi – seems a promising point of departure for the enquiry into the works of art as a history of objects, of things with active power, conditioning people and their social lives.

Historical studies offer various interpretations of works of art, but they always consider them as works of art, never as things. They frame these objects as expressions of human genius, artistry, knowledge and skill. ←9 | 10→Historians, apart from art historians, often use artworks as simple illustrations of various processes and political or social events. Thus, they tend to think about these objects as symptoms, manifestations, signs, or reflections of different situations, events and ideas. This approach denies the existence of the work of art in its own right and promotes its indexical role as a marker of certain events. Art historians are infuriated when historians use a work of art as a simple illustration in a textbook. But is their fury justified? The discipline of history of art has promoted art as a manifestation of certain periods: historic narratives distinctive from the history of style or artistic ideas. Are artworks merely reflections of the external historic processes, or are they active objects operating through time? Can they be seen as participants in the game between people and their institutions? Are they formative agents – operating irrespectively of the human will – shaping human actions, mentality, customs, living conditions? Is it history that produces art, or is it art that generates history and life?

Let us consider various objects, examples of things, which functioned in the visual culture of the Late Middle Ages.

I.1. From Kunstgeschichte als Geistesgeschichte to a posthumanist theory of the agency of things

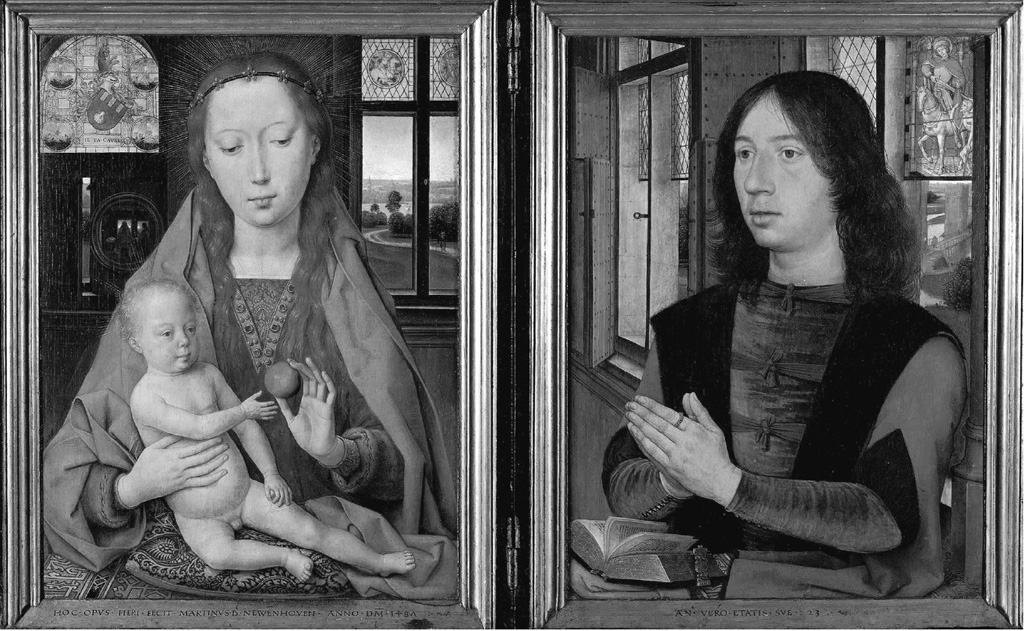

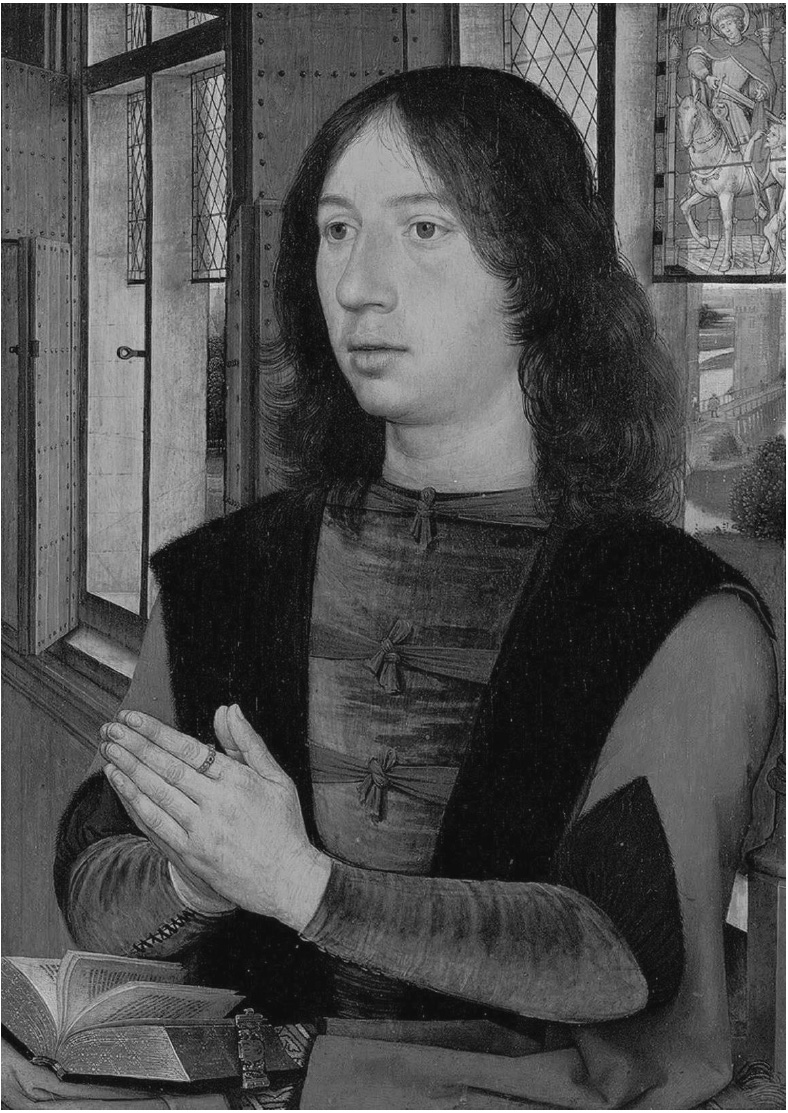

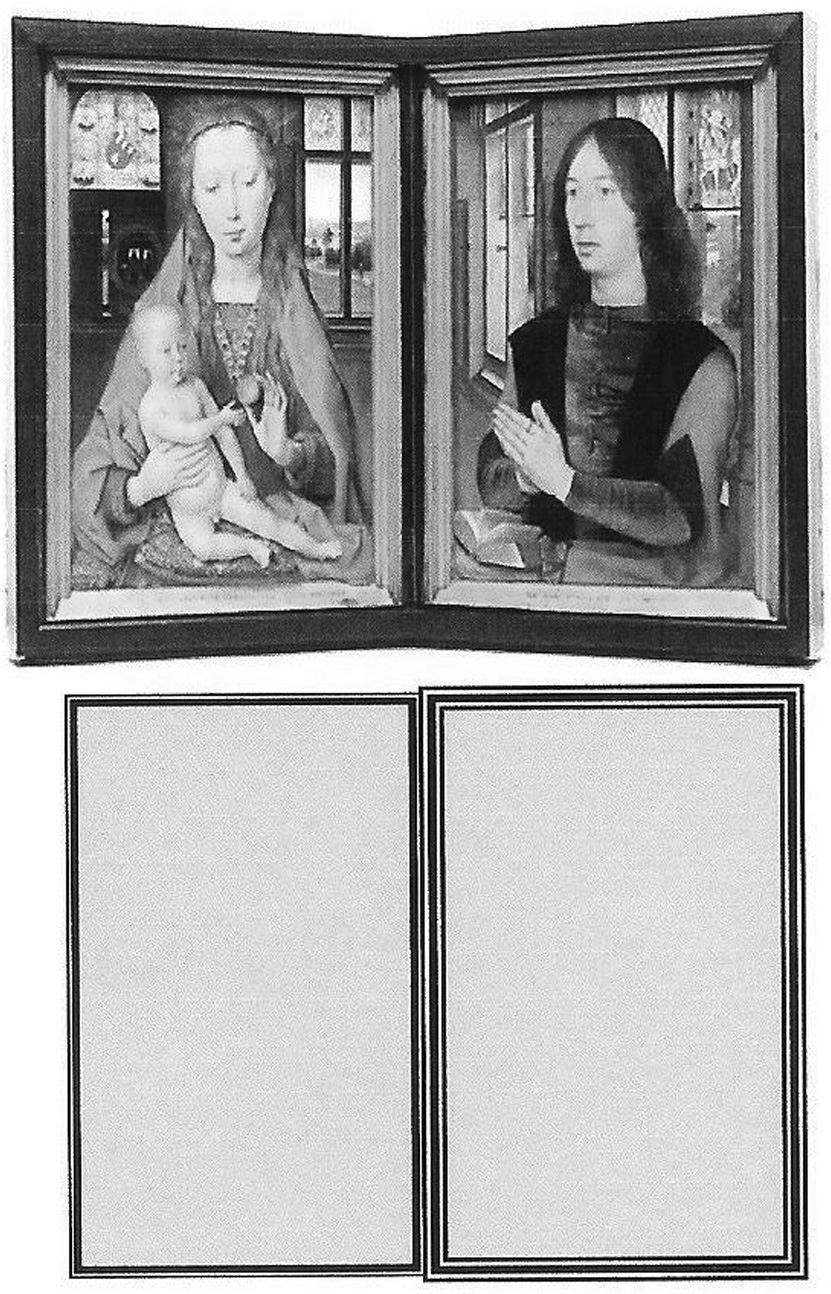

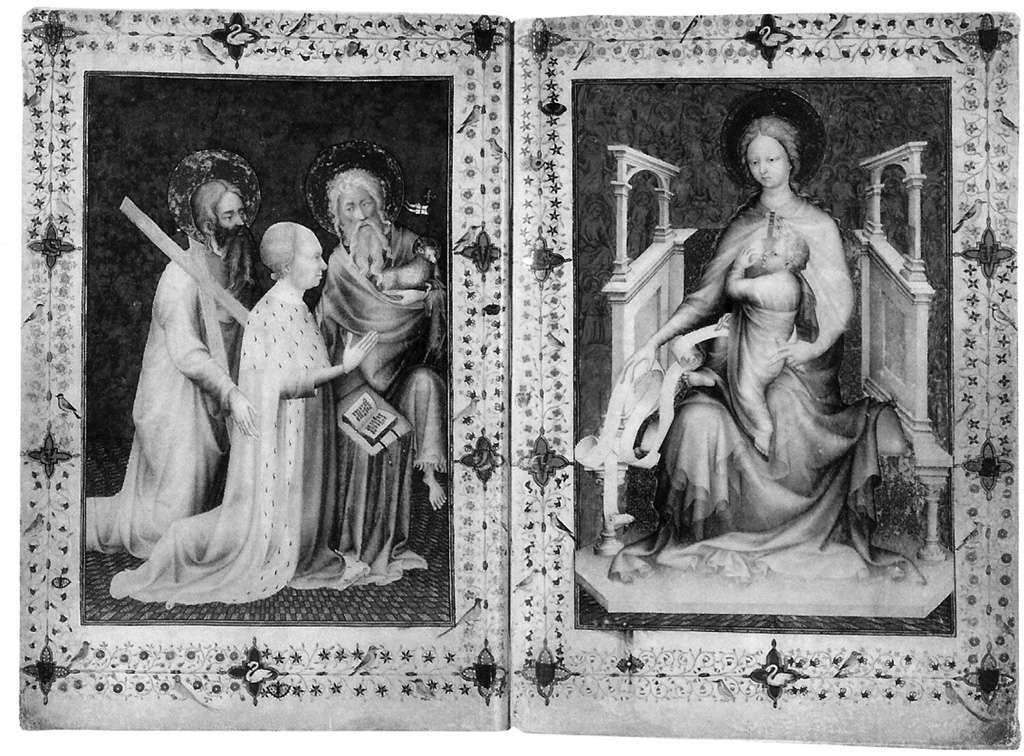

The celebrated work by the Netherlandish painter, Hans Memling, the Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove [fig. 1] can be interpreted in numerous ways according to the different methodologies introduced by the history of art.

At the turn of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, Max Dvořák and Aby Warburg developed a theory of history of art as a universal history of ideas (Kunstgeschichte als Geistesgeschichte), in which works of art were symptoms of a “great artistic stream of the spiritual development” (Dvořák). In this perspective, Memling’s diptych becomes an expression of specific socio-religious circumstances and a philosophical and intellectual formation: for Dvořák it was an example of nominalism – apart from the realism one of the main philosophical and theological views of the Late Middle Ages. Traditional realists, including scholastics such as Thomas Aquinas, considered the ideas of things (the universals) as actually existing; the things available to our senses were merely a material realisation of the divine ideas and the tenets of faith. In turn, the nominalists set intellectual cognition far apart from faith (the famous “Occam’s razor”), only specific things (res) were tangible, real entities, whilst the universals were for them only names of these things – nomina, merely conventions invented by the human mind. They promoted the empirical cognition and analysis of phenomena – of these res. According to Dvořák, the descriptive naturalism of the Netherlandish painting was a late reflection of the nominalist thought, whilst the earlier Gothic idealism was linked to the philosophical realism.

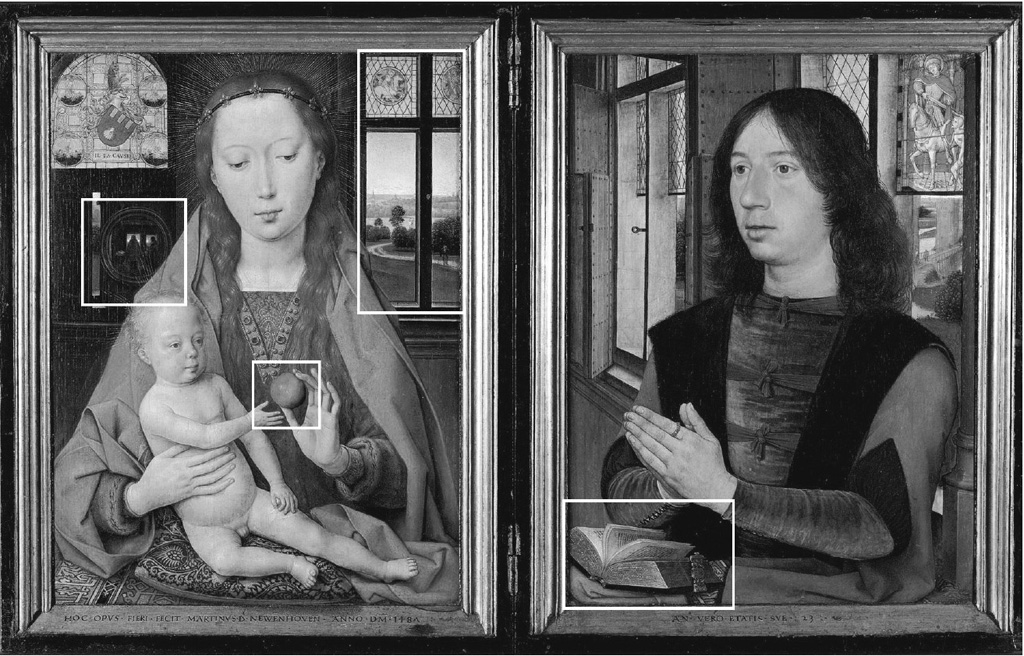

In another great theory of history of art, the iconology of Erwin Panofsky, the work of art was a symptom of the historic cultural situation, for instance of the late medieval patrician culture and its new type of private devotion (devotio moderna), which is manifested through a code of hidden symbols. Objects, gestures and situations, shown as seemingly ordinary, were to covey a deeper religious meaning: theological, liturgical, sacramental. In the case of the said diptych, it referred to the piety of the young man depicted, and addressed the purity of his soul and hope of salvation. The painting does not represent, it cultivates theology – argued Panofsky. The Nieuwenhove Diptych is a symbolic profession of faith in the Incarnation, the virginal motherhood of Mary: her purity, as well as faith in the power of avid, private prayer, which purifies the soul of the young donor. This interpretation is based on the deciphering of various hidden symbols, which formulate an integral message: the unblemished mirror (speculum sine macula from the Canticles), the window as the symbol of the soul, the book– a symbol of the Gospels and the mystery of the Salvation of mankind, the fruit – a symbol of the lost spiritual innocence enjoyed in Paradise (gaudium paradisi) [fig. 2]. The art historian deciphers this hidden symbolism, and their reconstruction provides a deeper understanding of the civilization. This includes its mentality, religious faith, beliefs and the worldview of people from a specific period, milieu, and of a certain social status.

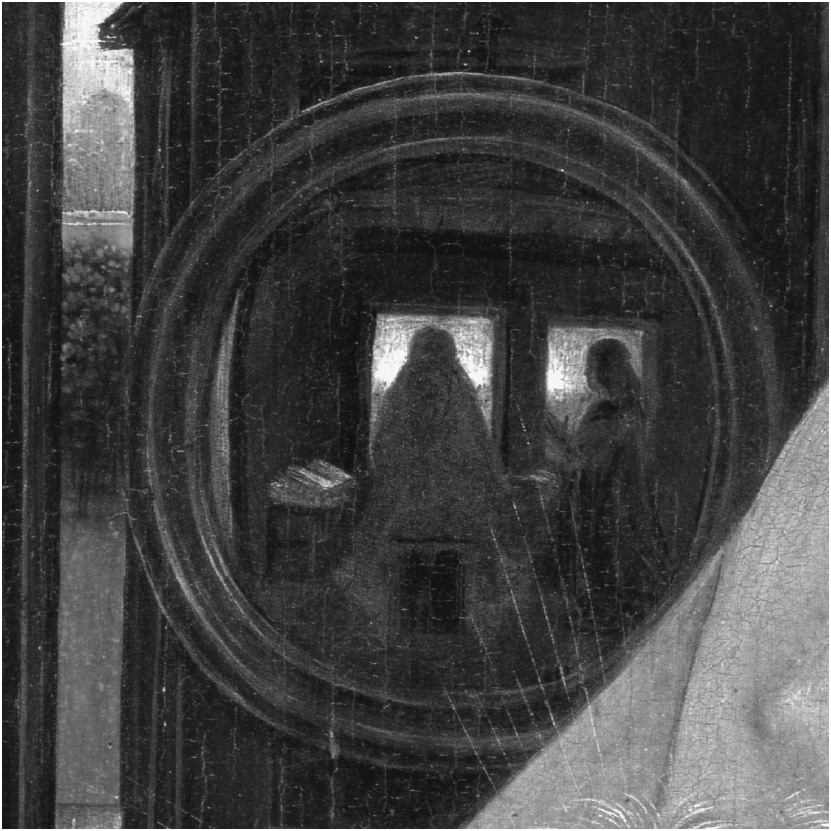

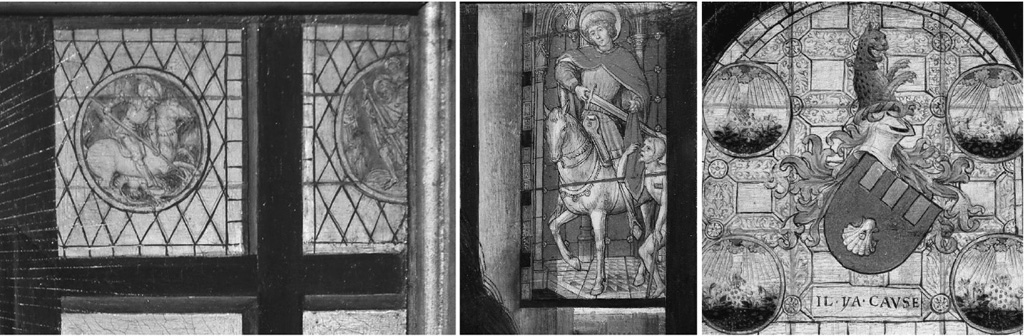

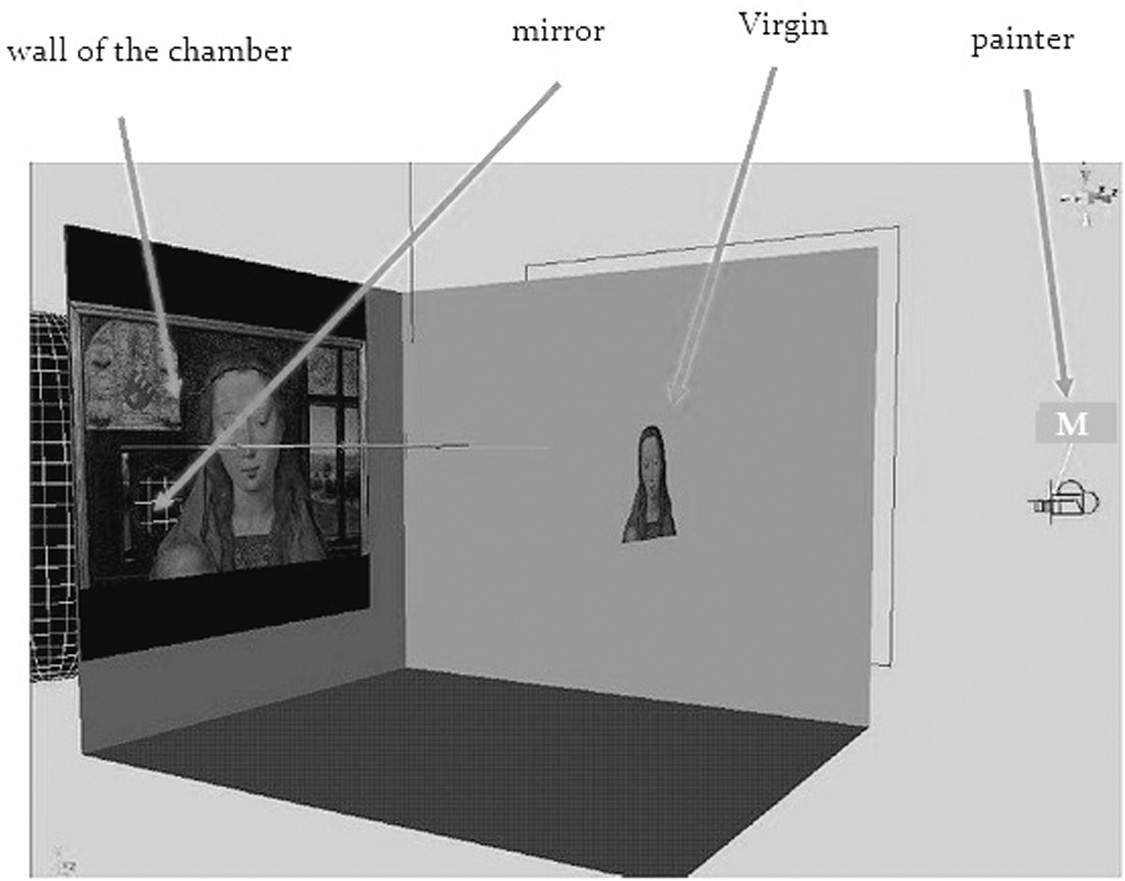

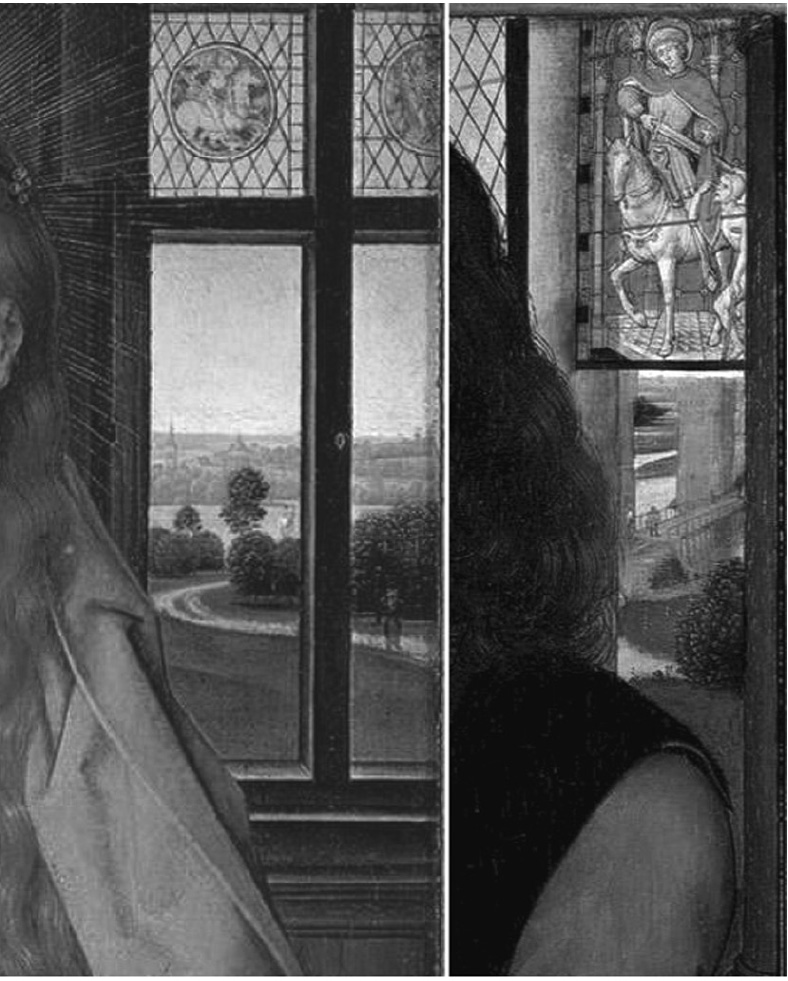

It is also possible to interpret paintings according to the category of social history of art – a materialist concept, most frequently the Neo-Marxist theory, which made use of the renewal of classical Marxism by Louis Althusser and ←11 | 12→his numerous followers, including Pierre Bourdieu. The figures are depicted in a chamber, which opens to the suburban landscape through the windows. Nieuwenhove sojourns in his suburban residence. The mirror on the wall clarifies the scene [fig. 3]: we see the Virgin and Child, frontally through the window, and Nieuwenhove kneels directly at the Virgin’s side, in the same chamber, which annihilates the division into the wings of the diptych. It is not so much a devotional space, but a space that demonstrates the social status of the depicted. We see Maarten van Nieuwenhove, a young, twenty-three-year-old (as inscribed on the frame) patrician from Bruges, who awaits a great future, resulting from the position of his family, who for centuries had held the highest offices in Bruges (indeed he became a city counsellor, the captain of the town militia, and finally the mayor of Bruges). The stained-glass windows [fig. 4] show the saintly knights: George, Martin (the patron saint of the sitter) and St. Christopher, the patron saint of merchants, also considered to be a knight. Behind the Virgin there is a prominent coat-of-arms of the van Nieuwenhove family, fashioned after knightly models, with the motto Il ya cause (Nothing without the reason) and the emblems of the hand of God sprinkling the garden with water, the “new garden,” het nieuwe hof, linking to the family name. The aim of the work is to demonstrate the donor’s high status and aspirations to the knighthood – a testimony to the social change, conditioned by the economic wealth of the patricians, that was taking place in the fifteenth century.

The works of art, such as the Memling’s diptych, were interpreted in a yet different way by semioticians and structuralists of the second half of the twentieth century, and proponents of the post-structuralism, deconstructivism, intertextuality, narrativism, new historicism, post-sacrality, alter-globalism, and all postmodernists, who appeared after the Neo-Marxist revolt in 1968 in France, and spread across America, England and Germany. Their ideas were employed by art historians such as Svetlana Alpers, Mieke Bal, Keith Moxey and many others. It was the time of the so-called linguistic turn – or semiotic – which substituted the great theories with the linguistic message produced by a single work of art, created again and again, by new beholders in various periods. Thus, the work of art is free of the constraints of intentions of the historic author-maker. In such a way, the contemporary viewer interprets the diptych through his/her own experience and knowledge, for instance considering the memory of a trip to Bruges or an image on a kitchen apron, which is present in her/his desacralized daily life [fig. 5]. This approach is promoted by the theory of intertextuality, which welcomes interpretations of works of art through other cultural texts – contemporary with the work, preceding its production, and above all subsequent to it chronologically: paintings, images, representations, for which the work forms a screen for personal projections of the beholder [fig. 6]. The ←12 | 13→post-structuralist will search for the viewer inscribed in the painting; he/she will encourage the beholder to find his/her place in the imagined space, to ask oneself various questions. Where is the mirror? Where did the painter and the viewer stand? Who looks at what? Who is actually reflected in the mirror? Who sees what? [fig. 7]. The post-structuralist encourages a fresh re-enactment of the internal structure of the painting, which depends on the viewer who has just encountered it. This interest is shared between the post-structuralism and the anthropology of images as theorized by Hans Belting.

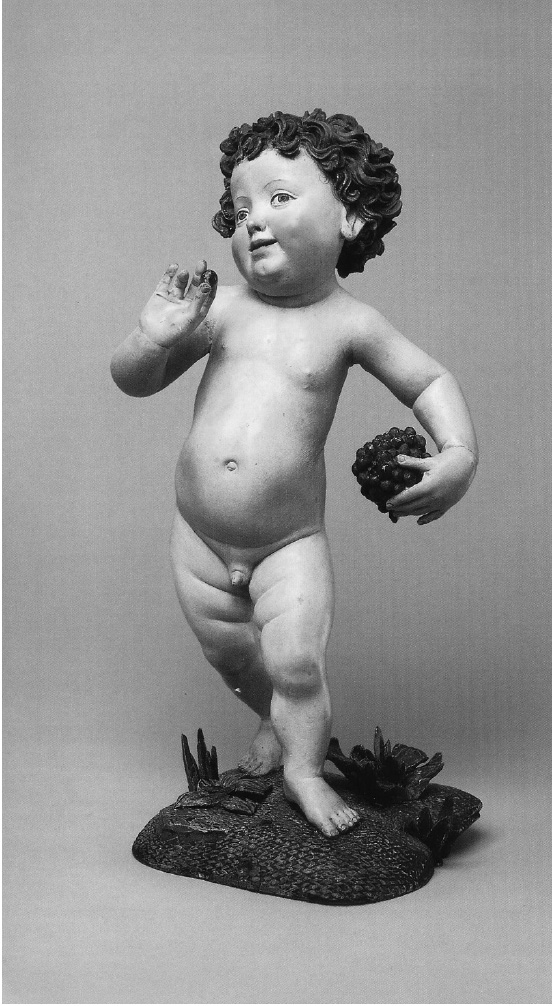

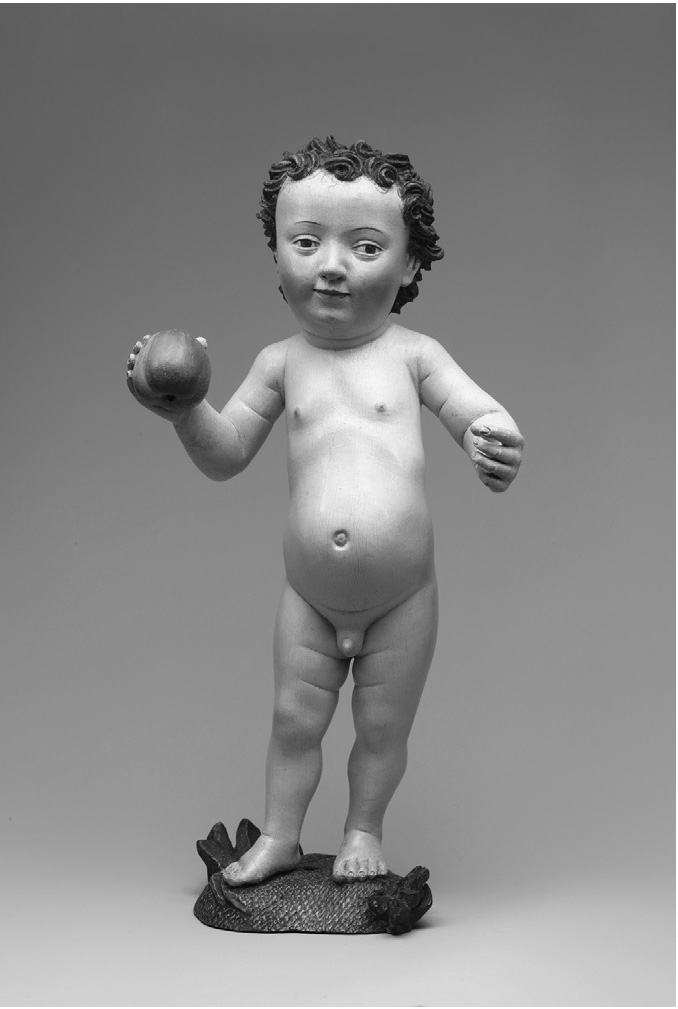

Postmodernism was at times linked with gender theory of history of art – feminist, homosexual and queer – though it is an independent methodological strand, based on Neo-Marxist materialism and empiricism. For instance, in 2005 Andrea Pearson located in the diptych the concepts of growing up and adulthood of men in the fifteenth-century Netherlandish society. She considered the painting to be an expression of fears of homosexuality and a lecture on the physicality of young men and boys, facing their sexuality, physiology, and the torment of nocturnal emissions, confronted here with the purity of Christ and the Virgin. They are in a way pardoned through the Incarnation of God in Christ, whose human nature included also the gender and (unexplored, but present) sexuality (hence the motif of the so-called showing of Christ’s genitalia – ostentatio genitalium) [fig. 8]. According to the postmodern theory Memling’s diptych presents a potential identity model for contemporary young men, whether of the macho type or more feminine. We can even call this a subversive model for ‘metrosexual’ hipsters or emo boys [fig. 9]. Perhaps, though Maarten’s clothes have little to do with hipsters’ fashion, or ‘emo-style,’ his hairstyle on the other hand, is perhaps closer…

Finally, the diptych could be also interpreted according to the phenomenological-hermeneutics, post-Heidegger and post-Gadamer, developed by fashionable thinkers such as Michael Brötje or Georges Didi-Huberman. This methodology seeks to understand the sacred and the spiritual emotions hidden in the painting, which can be observed, as if marginally, through the form: through what is relegated into the background, to the margins, to the borders. What is the visual fissure, is it literally present or just metaphorically alluded to? – for instance a space behind the half-closed window shutter, which introduces the external world, the realm of negotium (affairs), secular life allowed into a space filled with prayer and the presence of the holy figures [fig. 10].

In these various traditional modes of interpretation, the starting point is always the representation – the embodiment of the human form. All aforementioned interpretative methods remain deeply anthropocentric. Human beings, as makers and models for the representation, are active subjects in the communication between the image and the viewer. The object itself remains merely a screen onto which an artist or a beholder projects his or ←13 | 14→her vision. The man is in the centre: artist, patron, sitter, as well as contemporary viewers and subsequent beholders. At the same time, all we have is the object-thing. People, once active agents, are dead, and the contemporary viewer becomes a phantom, coming and going, elusive, momentary and fleeting. Should we perhaps look at the image as a thing with a life of its own, with its own agency and the power to act? The object could be an agent affecting human behaviour, relationships, and networks of mutual relations. Inevitably, the social fabric consists of humans and the non-humans that assist and condition men. These include animals, the biosphere, objects, mechanisms and devices; biochemical and biophysical components of life, and finally mechanical prostheses and artificial extensions of human bodies, from medieval glasses and lenses to cybernetic implants; lastly (as well) artefacts functioning in the cyber-network. This perspective on the history of mankind is assumed by the latest field in historical studies, namely posthumanism. In the West, it is advocated by Bruno Latour.2

Following Latour, let us consider: the role of a fifteenth-century diptych, operating as a thing. Its construction and the intended method of handling are telling. Diptychs were lifted and examined closely. They required manual handling to open and close them. Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove includes the portrait of the donor within a lavish frame, more luxurious than the frame of the second wing – which means that he was to be a “jar top” covering the image of the Virgin and Child, revealed only after the wing was open. [fig. 11] Only the third view, when the diptych was fully open, showed the portrait of Maarten. The form of the object directed the order of opening. The structure imposed a set sequence of views, prayers, and the presentation of the owner [fig. 12].

Used as domestic altarpieces, diptychs could be placed on tables or other pieces of furniture, open at a specific angle, which would prevent them from collapsing. They had to be viewed with wings set diagonally to the central panel, with scenes viewed at a specific angle. At times diptychs were treated as books, kept in cabinets or inside chests, sometimes in special cases, from which they were removed, unfolded, looked at and folded back again. Sometimes they would be hung on a wall on a chain; this way of displaying the diptych permitted them to be closed or opened easily, revealing a chosen side of any wing. This positioning enabled the gaze of the donor to meet that of the holy figures – the Virgin or Christ – thus ensuring that the figures communicate with each other, a crucial aspect that would have been lost with wings fully open.

***

History of art begins to employ the posthumanist methodology, when it turns to the study of mobile objects, which engage various senses and shape human surroundings.3 Undoubtedly, this strategy is the future of the discipline, which ←20 | 21→from its origins deals with objects-things. How can this non-anthropocentric, non-humanist method be employed in art historical studies? It is possible only through approaching artistic objects, not as artworks but as objects, things created by people, but gaining their own entity, their own power and agency in shaping humans and the common environment. It is not my aim to simply apply the general posthumanist theory to surviving examples of late medieval art. It is not the purpose of this book. This theory provides the creative stimulus for the present study and is not used as a methodological background for interpretations of the artworks created in the past.

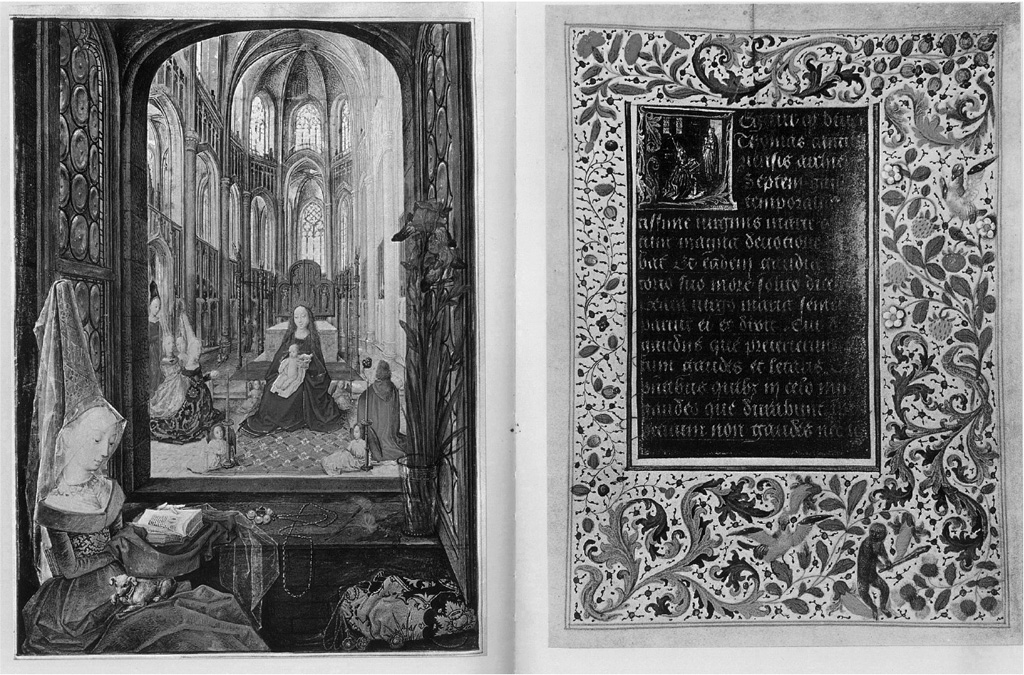

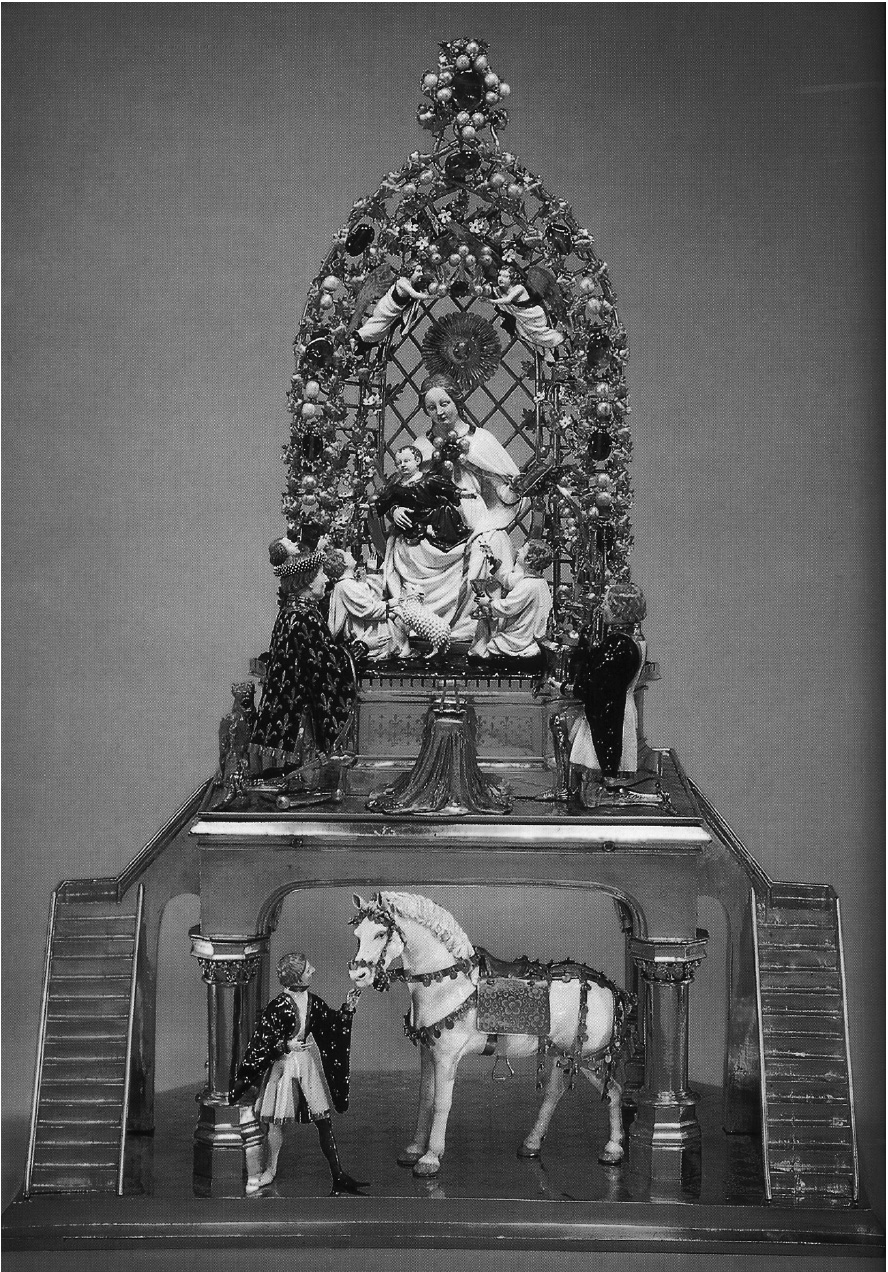

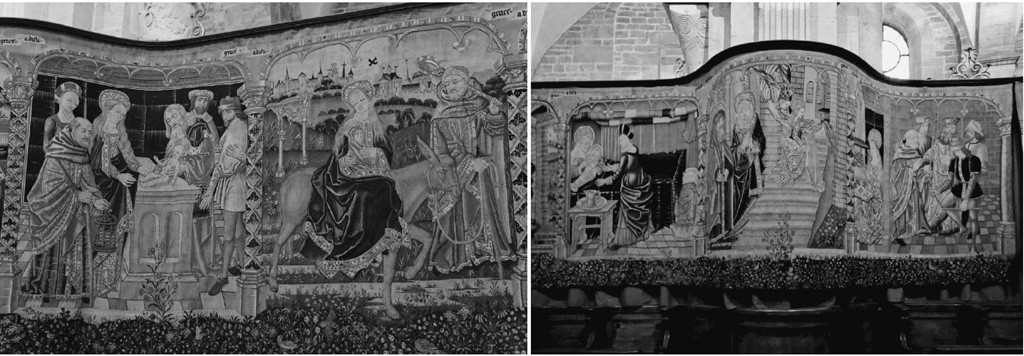

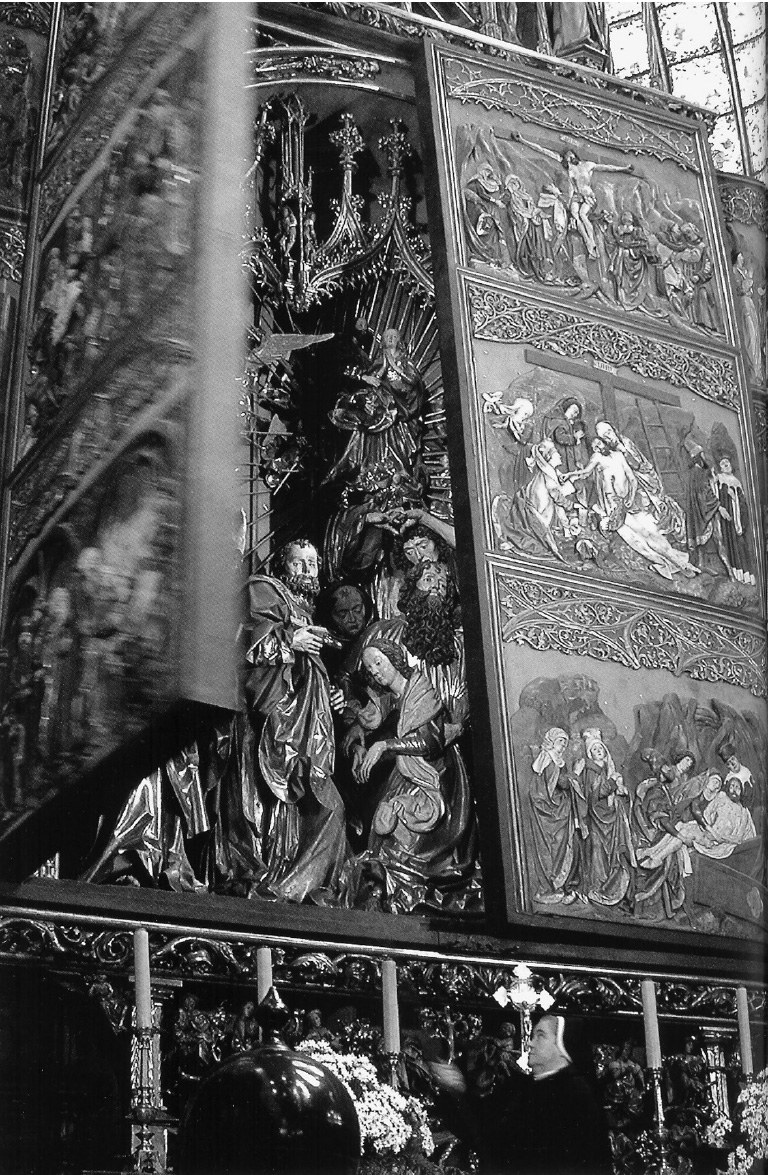

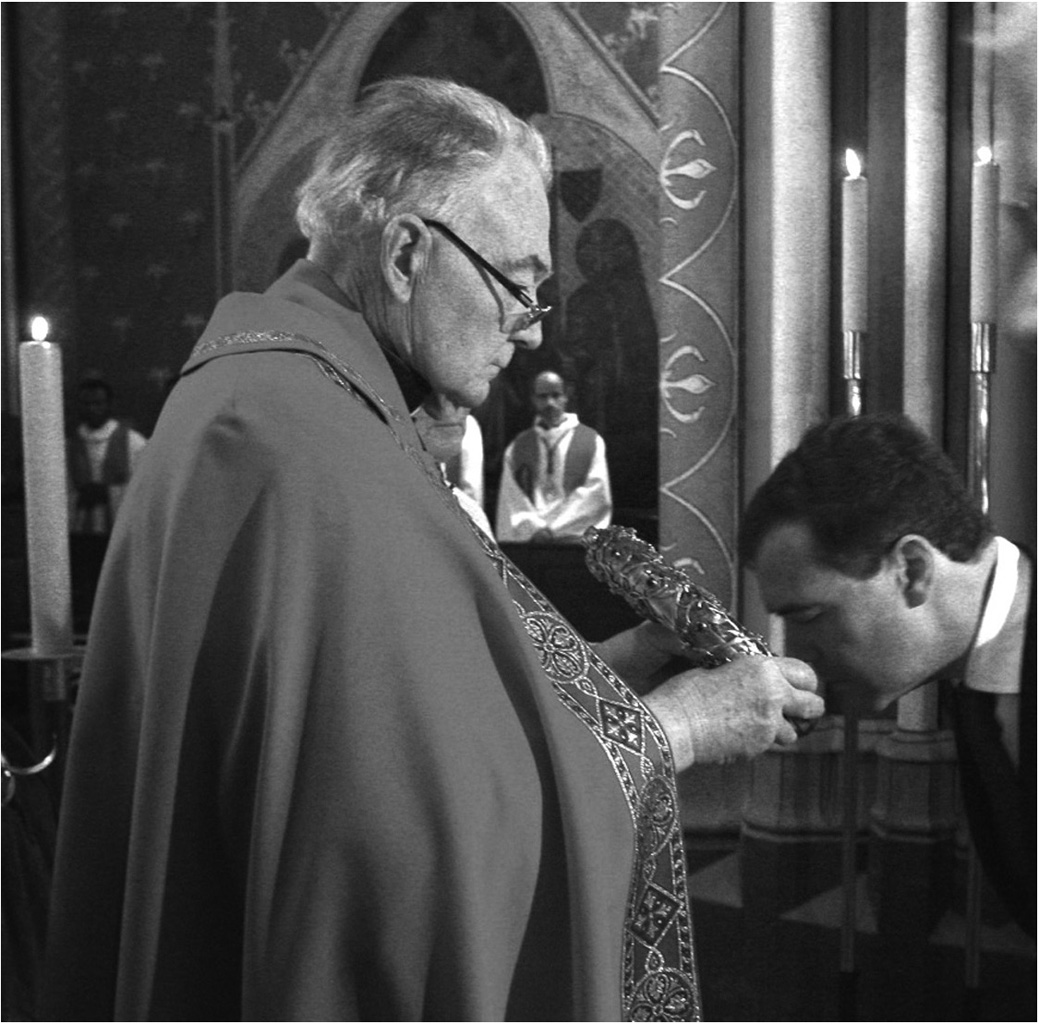

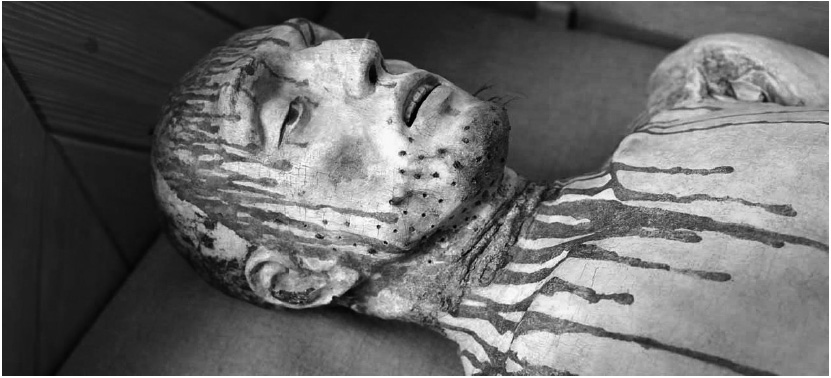

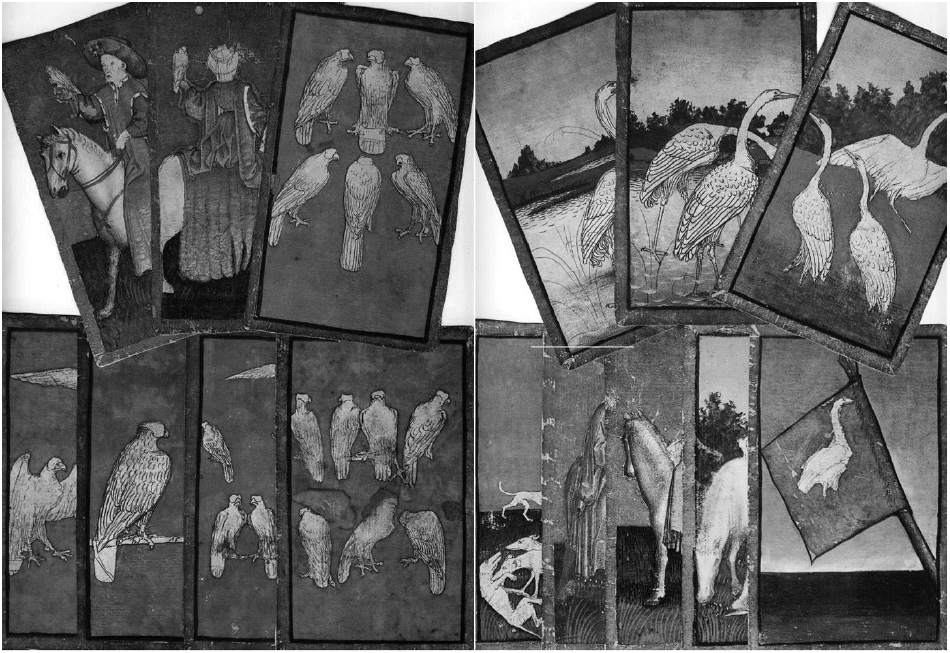

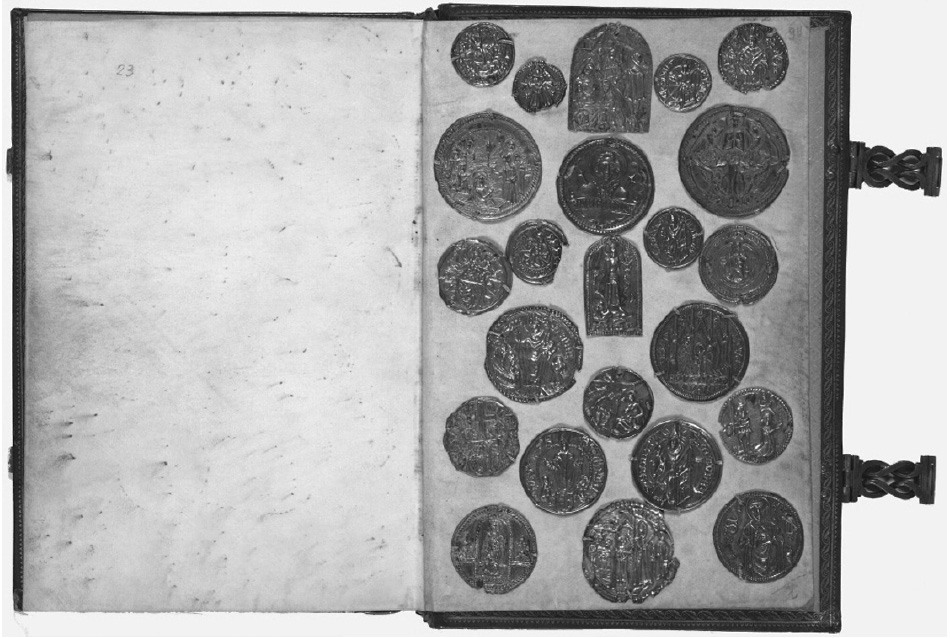

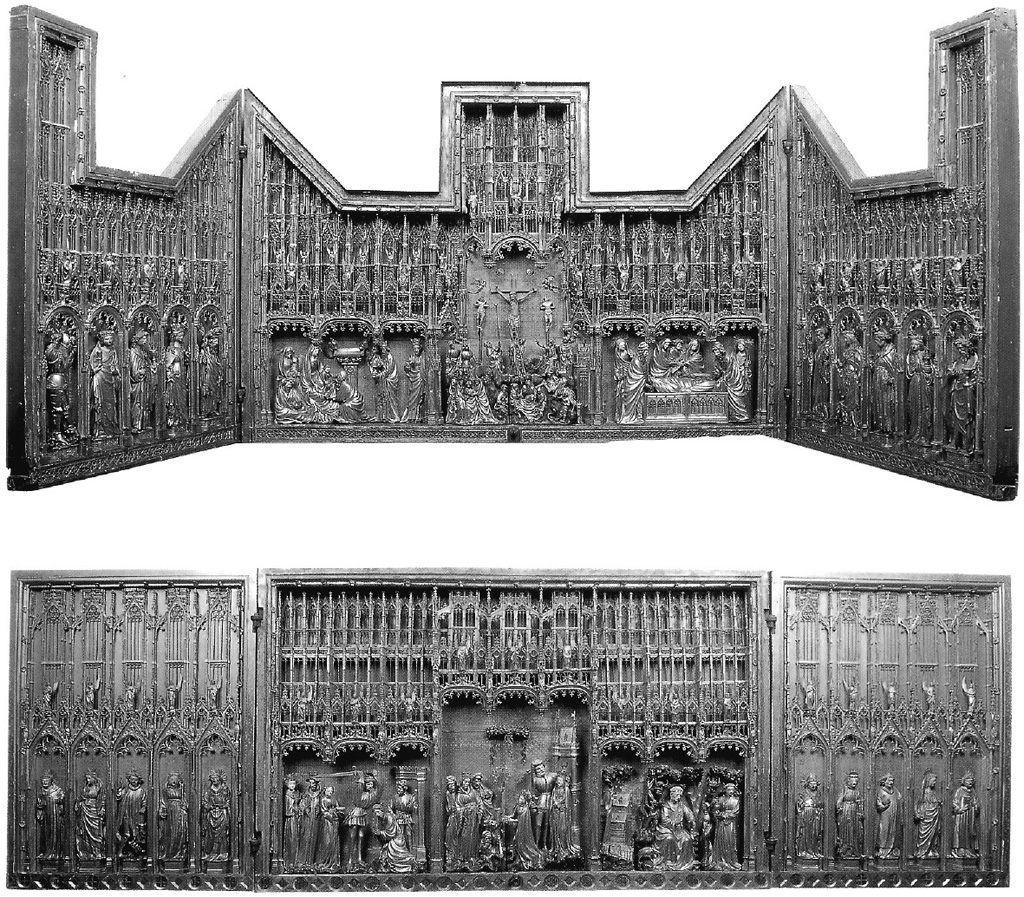

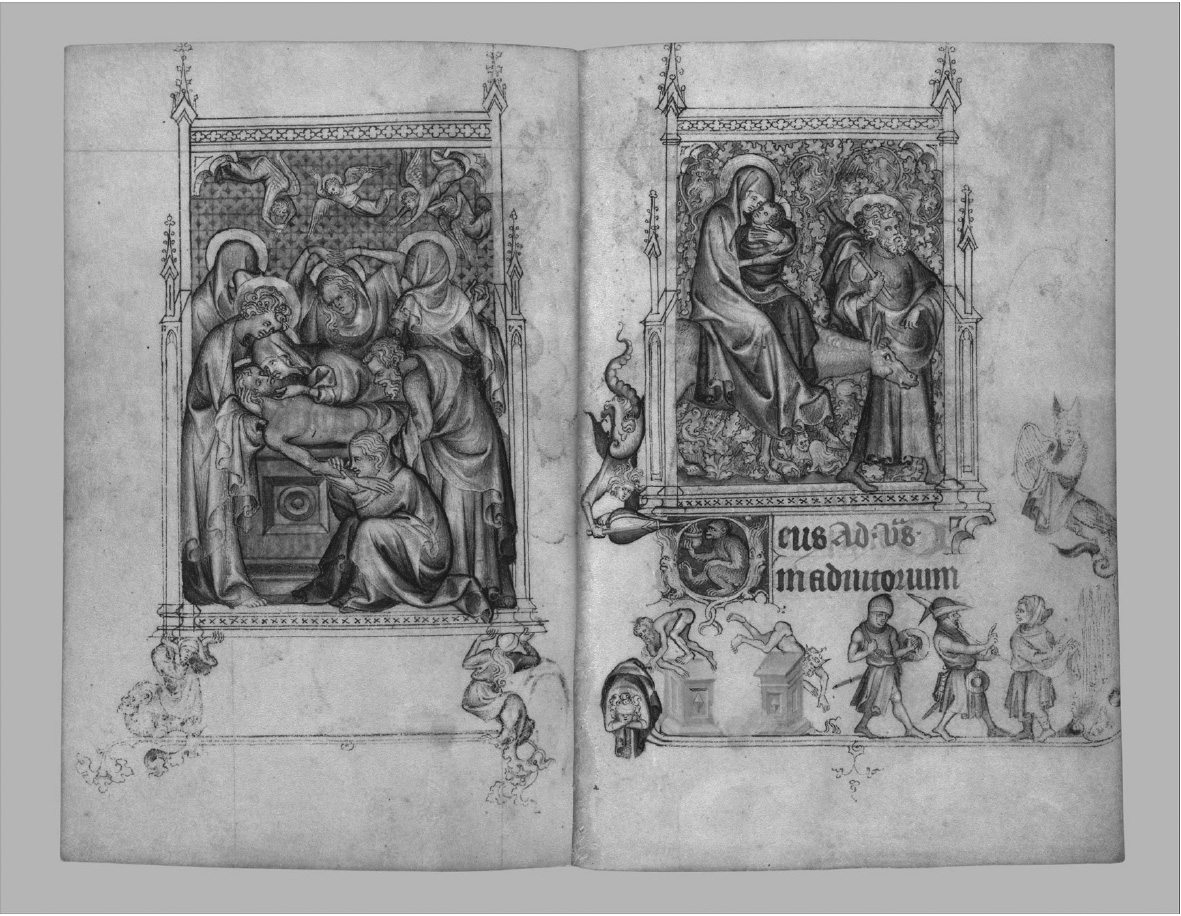

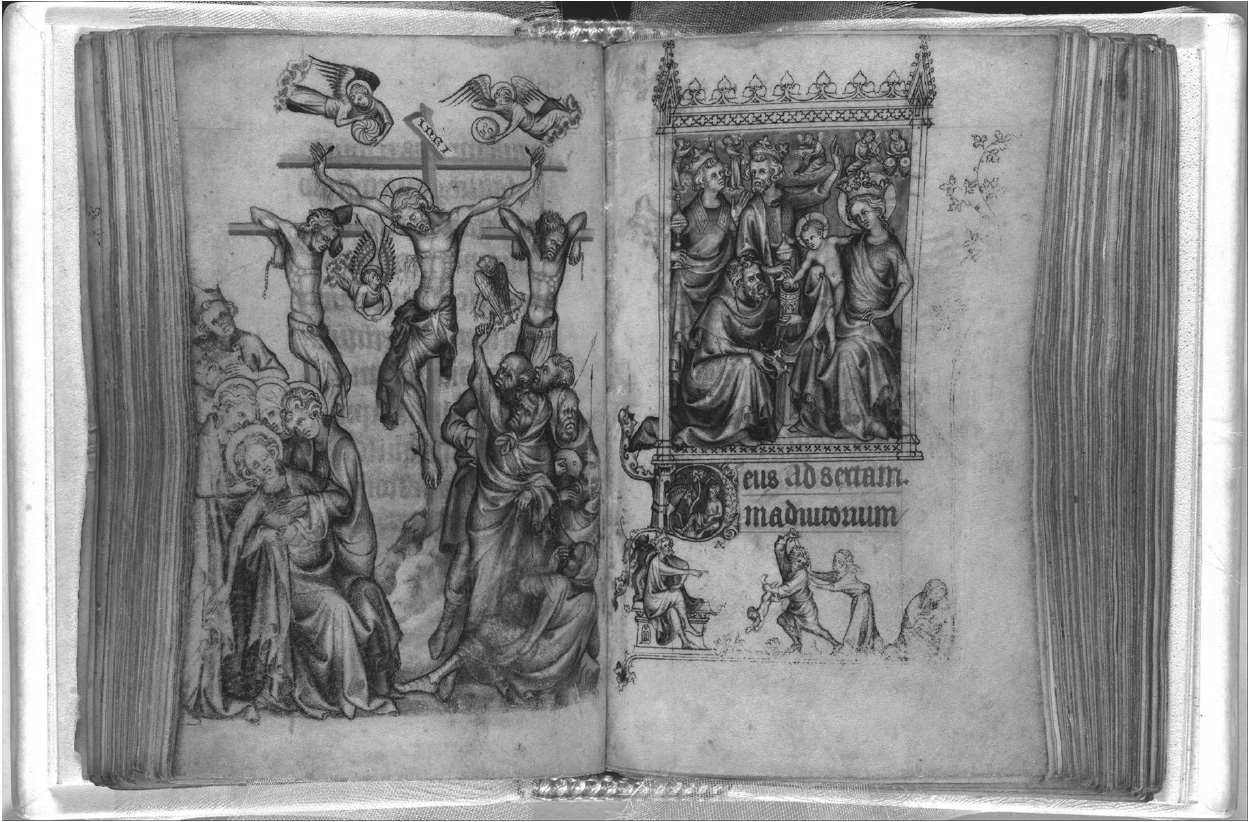

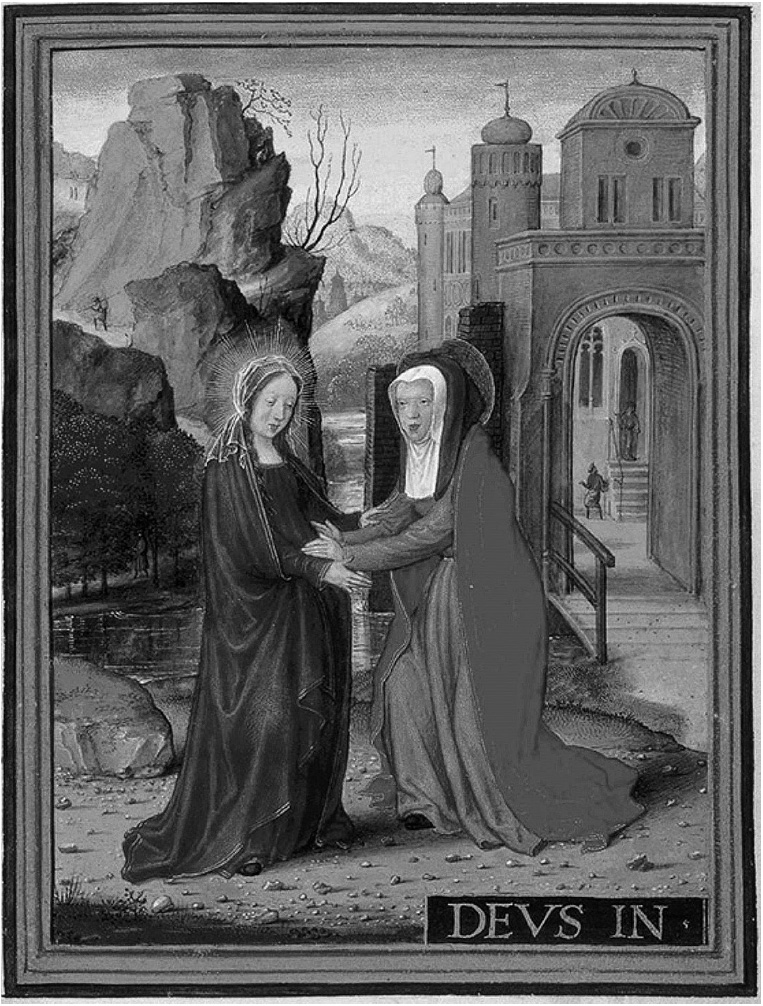

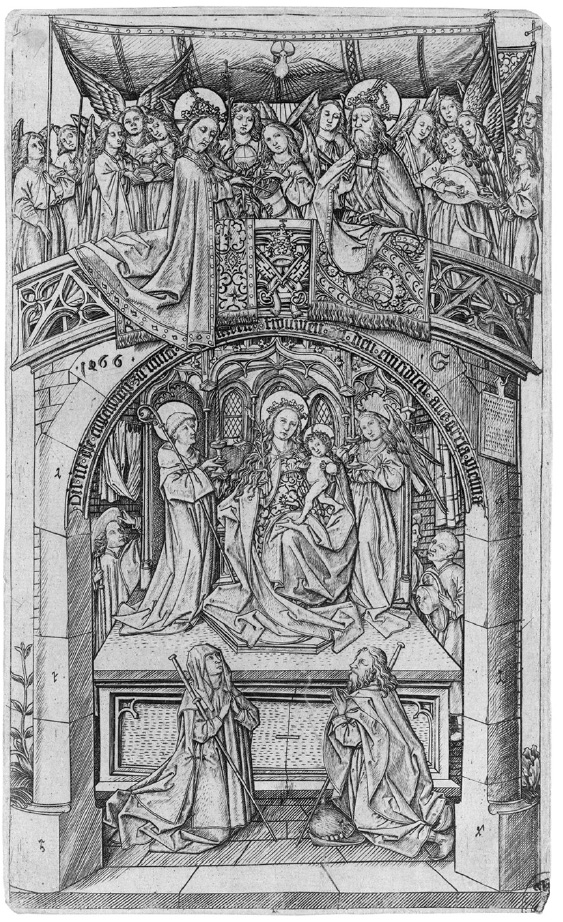

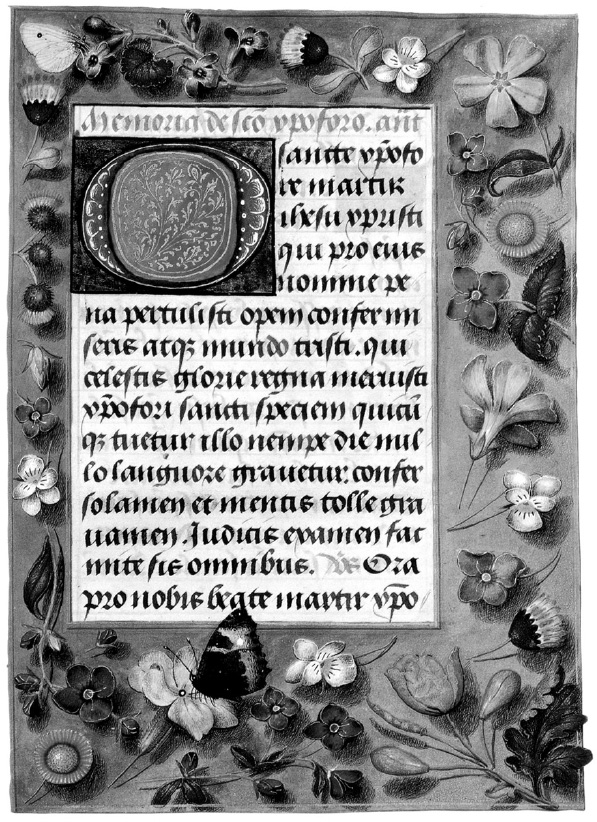

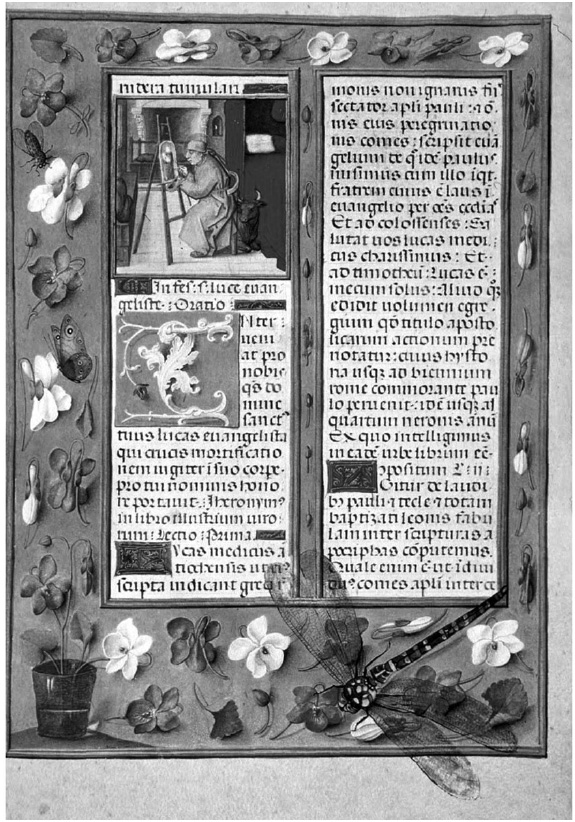

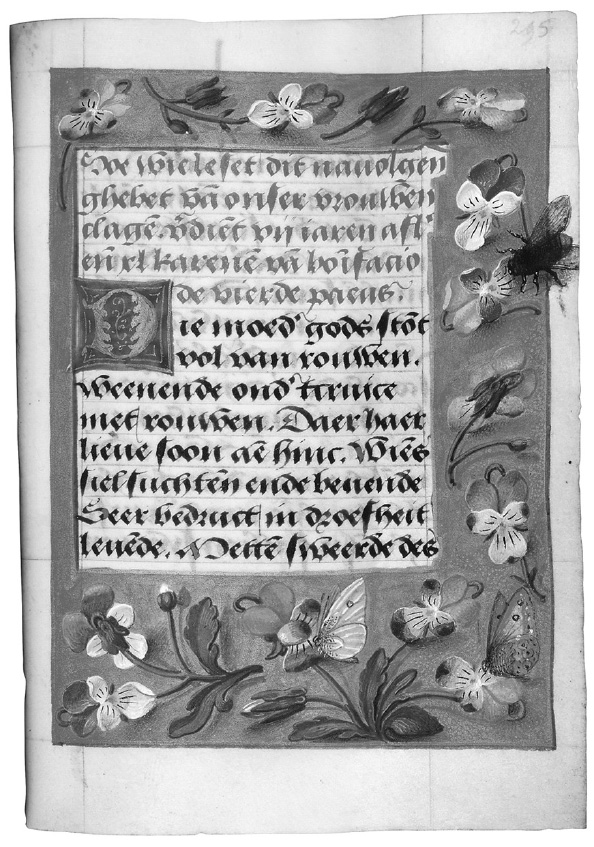

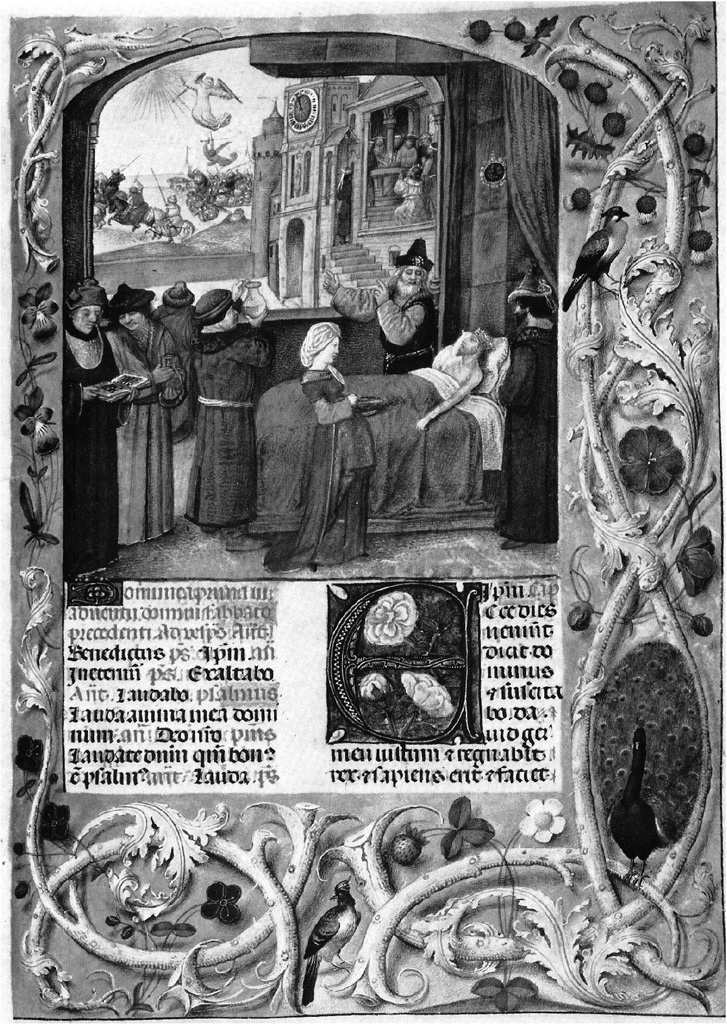

Fifteenth-century works of art often invited manual handling: the opening of books, flipping through their pages, searching for a prayer or a specific illumination [fig. 13]; precious metalwork was placed inside and taken out of chests or boxes for display [fig. 14]. Tapestries were folded and unfolded, to be hung on the walls on special occasions, not necessarily flatly [fig. 15]. Large, medium and small winged altarpieces were constantly open and closed [fig. 16]. Figures of Christ, at times with moveable parts, participated in the Easter liturgy [figs. 17–18]. Miniatures were cut out from illuminated manuscripts and stuck on walls; individual prints were widely disseminated [figs. 19–20]. The world of artefacts that constitutes the visual culture of the Late Middle Ages was also haptic, appealing to the sense of touch. People interacted physically with artworks through handling them, manipulating them, holding them in their hands, and at times even fondling, caressing or kissing them. A common ritual involved touching and kissing relics; through the physical contact blessing for the faithful was imparted [fig. 21]. The Easter ritual of Depositio Crucis included a range of physical manipulations from the moment when the figure of Christ was removed from the cross, carried in a procession and finally placed inside a tomb. The realism of these operations, based on touch, was enhanced by the softness of Christ’s body and His skin, evoked through lifelike polychromy or through surfaces covered in parchment and animal skin [figs. 22–23]. The naked figurines of the Christ Child were caressed, kissed, bathed by nuns and later dressed in handmade robes, according to a specific female practice that developed in nunneries [figs. 24–25]. Prayer nuts were meant to be held and turned in hands. The pages of illuminated manuscripts and books were flipped. Small diptychs and triptychs, as well as panel paintings and tondi, were held in hands, to be looked ←21 | 22→at and examined, or at times they were placed on a table or shelf or hung on a wall. Prints and playing cards were constantly rearranged, and displayed in series or packs [fig. 26]. During pilgrimages they were carried as part of a pilgrim’s personal belongings, and were later kept at their homes, to be touched as plaquettes-talismans [fig. 27].4

All the actions described above confirm that fifteenth-century art was an array of moveable, active things that were manually operated but which also had the ability to manipulate their beholders.

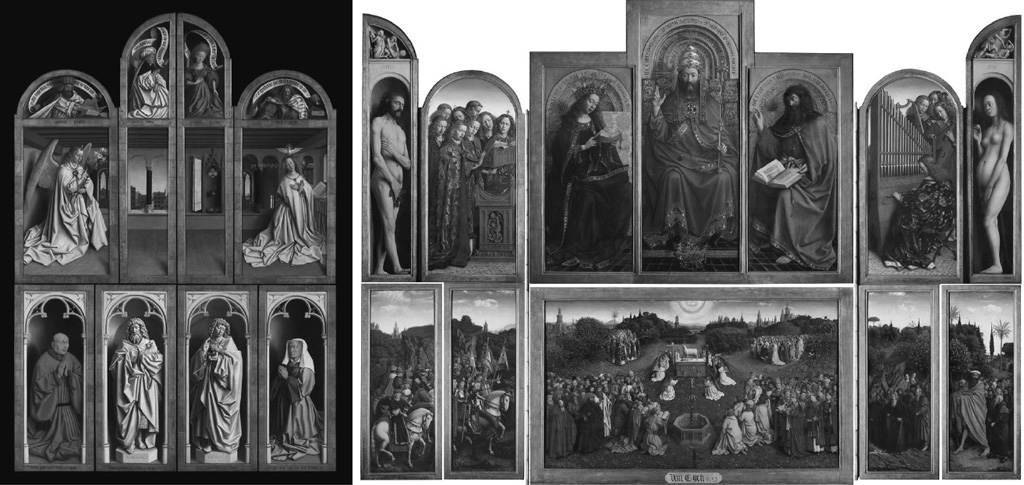

I.2. The illusion of the objectivity of the work of art

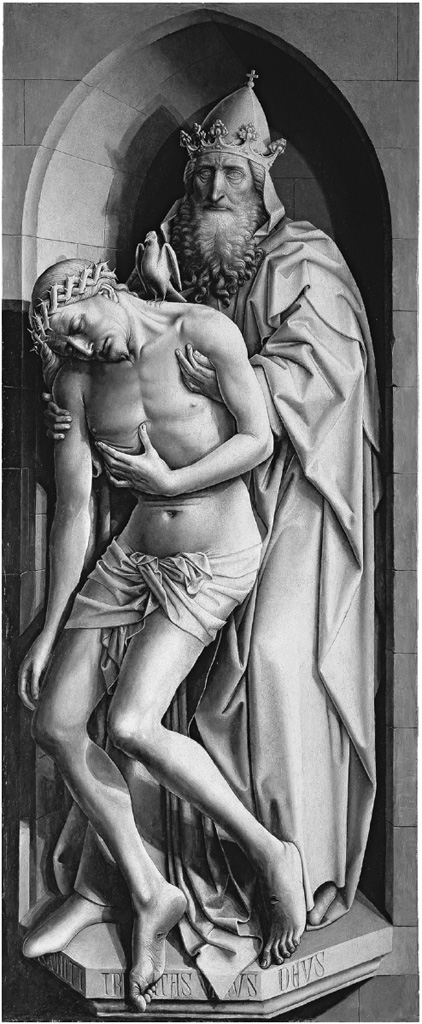

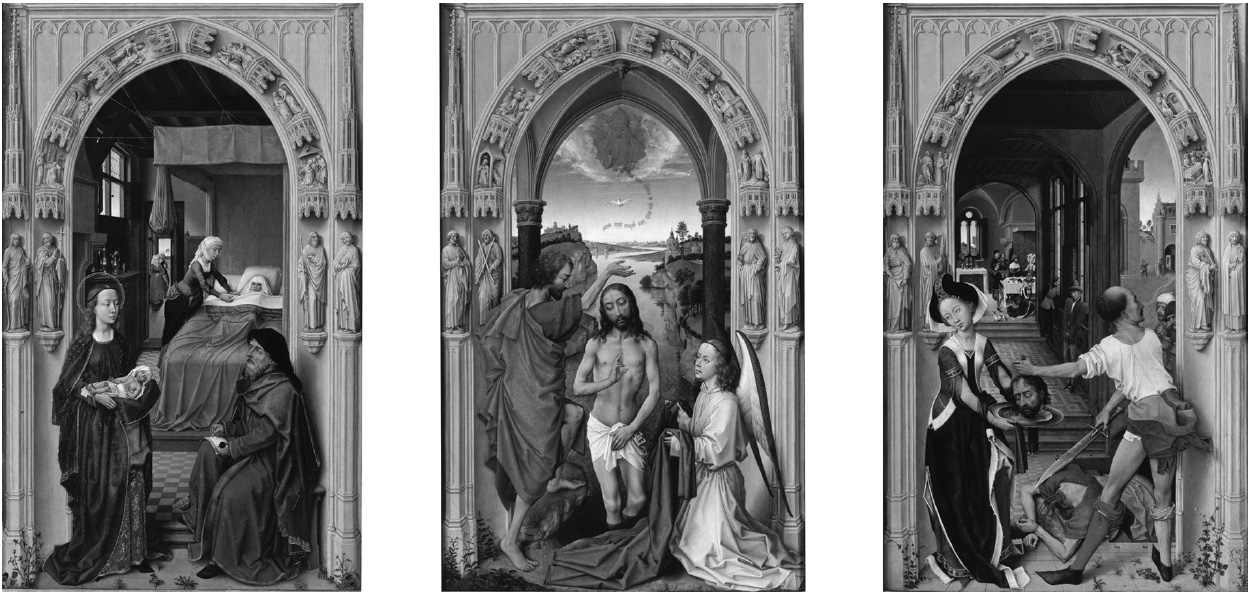

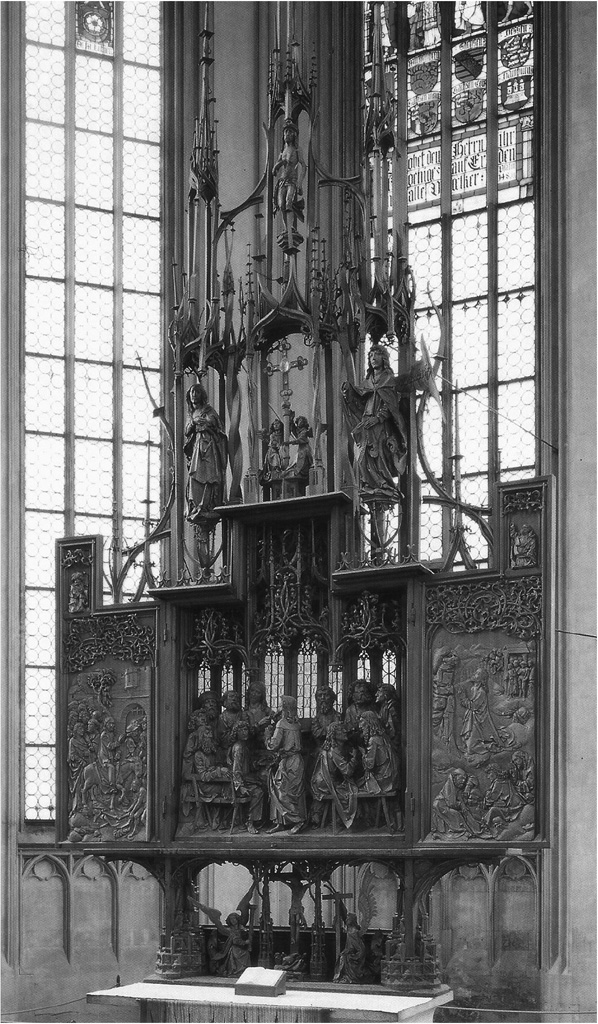

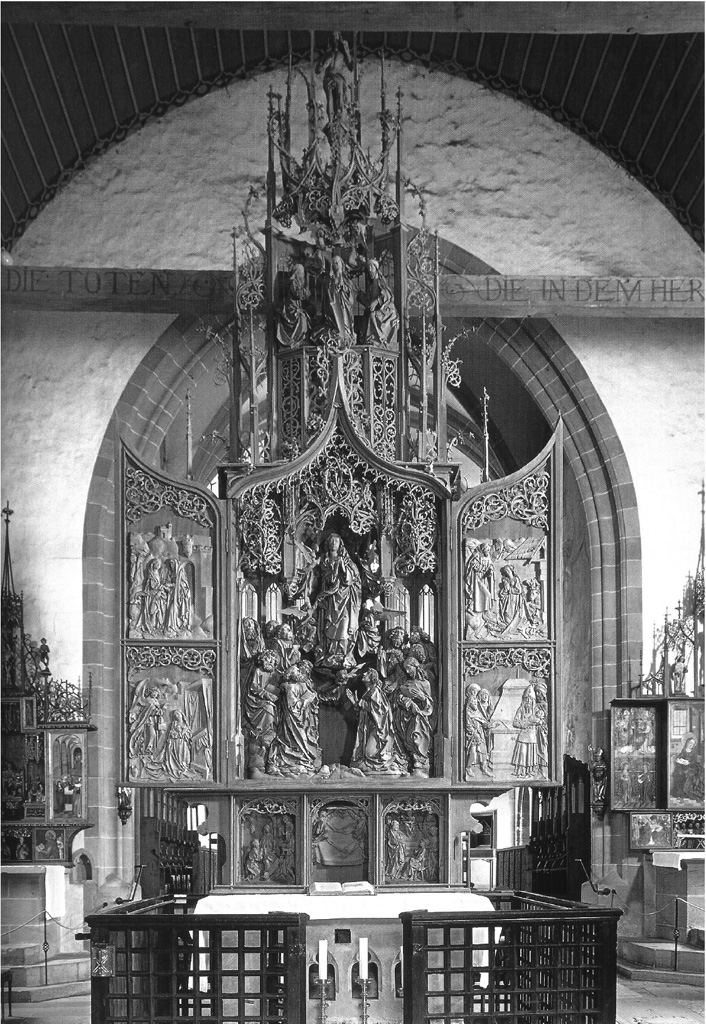

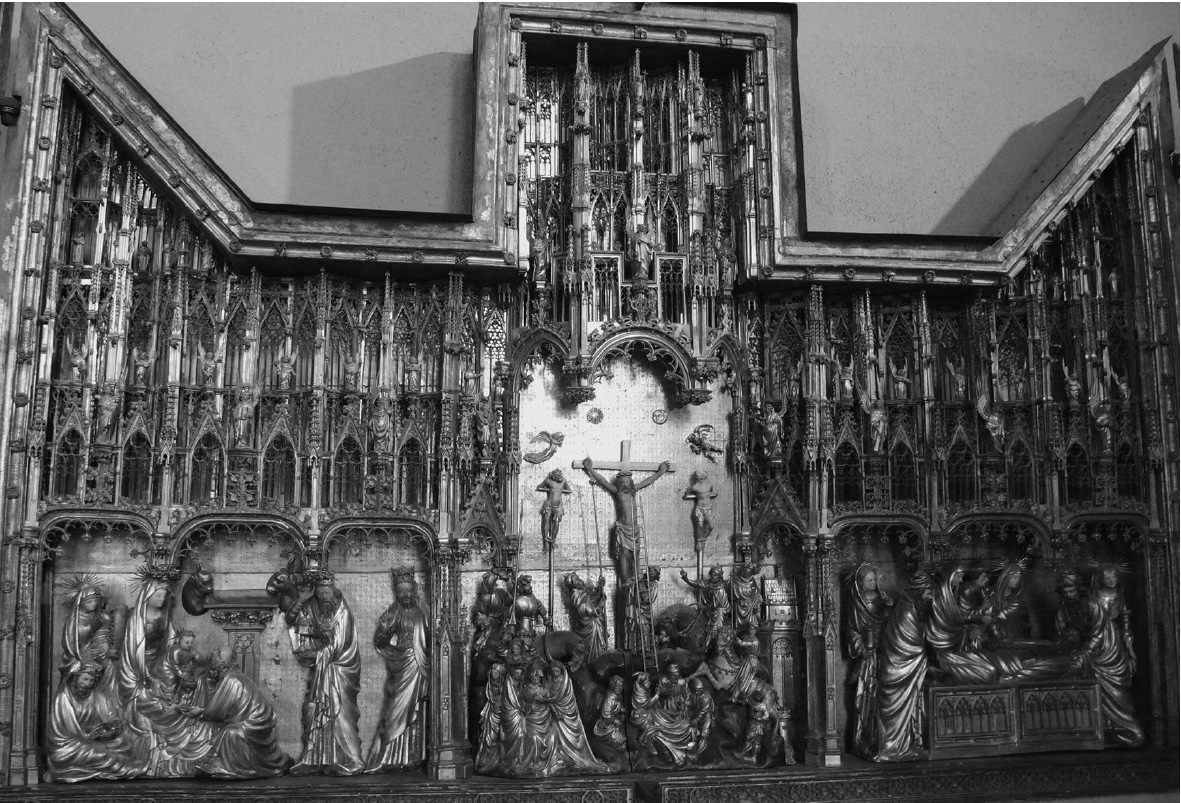

Illusion always demonstrates the objectivity of an artwork, and the materiality of the artist’s product. Fifteenth-century works of art often define themselves as things. They constitute and display their status as objects, skilfully crafted through an artistic technique. Through the illusion of specific materials, they mimic, and become technical things, obtained through the shaping of the matter. They pretend to be something else. A painted polyptych imitates a stone wall with niches filled with sculpted figures (The Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck, The Throne of Grace by the Master of Flémalle and many others) [figs. 28–29]. Triptychs formed of three painted panels by Rogier van der Weyden (The Miraflores Altarpiece and The Altarpiece of St. John), Dirk Bouts or Hans Memling imitate in reduced format a stone façade of a three-bayed building with elaborate architectural details and rich sculptural decoration [figs. 30–33]. The painted and carved Reliquary of St. Ursula by Memling [fig. 34] tricks the viewer into believing that it is an arcaded loggia, which opens to a vast landscape and various narratives. Rogier van der Weyden’s The Descent from the Cross in the Prado – a painted panel – imitates the predella of a carved altarpiece [fig. 35]. Monochromatic, unpolychromed wooden statues of various Netherlandish and German retables (Tilman Riemenschneider and others) at times imitate bronze or stone figures [figs. 36–37]. At the same time, lavishly gilded retables pretend to be large scale goldsmiths’ works (altarpieces by Jacques de Baerze, triptychs from Champmol Charterhouse) [figs. 38–40]. Numerous book illuminations painted en grisaille suggest that they are carved elements or elaborate drawings [figs. 41–42]. Manuscript folia unfold like diptychs, whilst small diptychs open in the same way as codices [figs. 43–44]. Miniatures imitate paintings [fig. 45]. Prints at times pretend to be sculptures, paintings, or fragments of architecture, such as stone portals [figs. 46–47]. When a fly, a dragonfly or a butterfly rests on the folio of an illuminated manuscript covered with flowers and foliage, or when a snail or a fly moves along the bordure, we grasp fully and clearly that we do not handle a fragment of a meadow or a garden but an artificial object, produced from parchment or paper [figs. 48–51].

Precisely because these objects pretend to be something materially different, they force the viewer to notice their objectivity, their status of being a material thing – a material painting, figure, sculpture, book, sheet of paper or parchment. Through imitating a foreign matter, they define their own materiality, the condition of being a specific thing. Through insisting on this status, they separate the representation from its reality. This play with the viewer reveals the existence of these objects as substantial and sensory things.

The illusion, which defines the image as both a material thing and an artistic creation, justifies their existence. In the fifteenth century, painterly ←31 | 32→illusion carried a theological message. Images – painted, carved, printed or drawn – had to manifest their materiality to disassociate themselves from representation, understood as re-presenting, or physically embodying the divine. In this way, they highlighted that devotion should not be directed towards them, as they are created from earthly matter, but rather that they are merely vehicles representing, signifying or symbolising the sacred: God, Christ, the Virgin, and Saints. Thus, the artworks stressed that they did not embody the divine or God, but merely represented it, not by impersonating (eliciting God’s presence in the world), but through illustrating the holy as a visible sign, indexing the sacred. Their role is to merely intercede between the earthly and celestial realms. They cannot be ‘invisible:’ they do not provide a direct sight of God “face to face,” as described by St. Paul the Apostle in his description of contact with God after final salvation (“For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face” – 1 Corinthians 13:12). Images do not embody the sacred, they do not have the power to summon the divine, nor to establish direct contact with God. They can and are constrained to being merely a screen of the holy, a mediation. Consequently, they should present themselves as things, to ensure that no one perceives them as the divinity, or the sacred figure – and so they are not venerated. This prevents the offence of fetishizing holy objects, making them idols or false gods – pagan deities. Thus, they avoid accusations of encouraging idolatry and allow worshippers to overcome their fear of eliciting iconolatry.

The late medieval images of Christ, the Virgin and saints bring together various central issues of the ontology and anthropology of images and image-making in Christianity. This includes the question of whether visualising the sacred – recreation, reflection, embodiment or simulacra of the divine – is legitimate and if it follows Christian doctrine. This uncertainty caused suspicion towards image-making and a fear of images coming to life, of their ‘magical powers’. This fear of the image is an integral and constant element of Christianity. Present already in Antiquity, when various figures of deities were bound with ropes and chains, and when Plato rejected all mimetic art and poetry as creating a semblance of real life, and as such creating death. This fear became apparent in subsequent outbursts of iconoclasm, sacrilegious speeches and turmoil. It also stimulated those theologians who were radically opposed to image-making. Most notably Jean Gerson, Pierre d’Ailly, Gilles Deschamps and Nicolas de Clemange, c. 1400, or Nicholas of Cusa around the mid-fifteenth century, proclaimed the futility of the material image (Plato’s eidolon) in relation to the intellectually and spiritually evoked image concealed by it (Plato’s eidon, idea). According to ecclesiastical reformers such as Jean Gerson, and the proponents of devotio moderna teaching, such as Geert Groote, as well as mystics including Jan van Ruysbroeck (Ruusbroec), the category of seeing and visibility formed a foundation of the religious experience. ←32 | 33→This category encompassed the mental image (contrasted with the material image) and experiencing the divine through imaginative, spiritual images, perceived in a sensual and physical way. This category was supposed to limit visionary experiences and – paradoxically – was a way to free the mind of the earthly images, which corrupted and constrained the soul. These material images merely recorded the spiritual visions, and at the same time as they stimulated the devotional imagination, they nourished the projection of other ‘pure’ images during meditative reflection– they became images of silence, and of contemplation. The material image aroused suspicion and various fears, including the fear of its magic power, its greed, which devoured pure spiritual sensations; of its potential to conceal what is true, holy, and metaphysical; of its superficiality, falsehood, and trickery; the emptiness of the material entity of every image and every representation, and finally the fear of substituting reality with mimesis.

Jean Baudrillard emphatically but perceptively defined this fear in his once celebrated book on simulations and simulacra:

[…] the Iconoclasts […] sensed this omnipotence of simulacra [that is of material images], this facility they have of erasing God from the consciousnesses of people, and the overwhelming, destructive truth which they suggest: that ultimately there has never been any God; that only simulacra exist; indeed that God himself has only ever been his own simulacrum. Had they been able to believe that images only occulted or masked the Platonic idea of God, there would have been no reason to destroy them. One can live with the idea of a distorted truth. But their metaphysical despair came from the idea that the images concealed nothing at all, and that in fact they were not images, such as the original model would have made them [divine prototype, divine idea], but actually perfect simulacra forever radiant with their own fascination. But this death of the divine referential has to be exorcised at all cost [i.e. through the destruction of all images]. […] the iconoclasts, who are often accused of despising and denying images, were in fact the ones who accorded them their actual worth, unlike the iconolaters, who saw in them only reflections and were content to venerate God at one remove. […] the iconolaters possessed the most modern and adventurous minds, since, underneath the idea of the apparition of God in the mirror of images, they already enacted his death and his disappearance in the epiphany of his representations (which they perhaps knew no longer represented anything, and that they were purely a game, but that this was precisely the greatest game – knowing also that it is dangerous to unmask images, since they dissimulate the fact that there is nothing behind them).5

I am not an avid proponent of the French philosopher and his diagnosis of contemporary society as a single, huge simulation through images ←33 | 34→(simulation of entity, in which images and visual symbols conceal nothingness). However, his remarks on iconoclasm touch upon the most important primary fears of the images.

The late medieval holy images of Christ were undoubtedly simulacra of the divinity: simulations of the existence of the real being through the illusion of the material image (to evoke the juxtaposition of the eikon-eidolon described by Plato in his Sophist, which defines the essence of simulacrum). They were – to cite neoplatonist theologian John Scotus Eriugena – similes, ‘simila’: semblances crafted by human hands, which simulate the existence of a prototype, a creative and uncreated divinity (creat et non creatur). As created, they do not create (creatur et non creat). They do not fashion an actual holiness, but merely repeat it, under the influence of the first causes of creation (the logos, the Word of God), empowered by the creative force (creatur et creat). In other words, as described by Lucretius (De rerum natura, Book 4, V, 30–53), they were simulacra as the external ‘skin’ of the actual entity. Divinity and sainthood were not directly present in them, as in a prototype (a holy icon or relics), but they merely resembled the holiness, constituting its ‘mark’ as different from Benjamin’s ‘aura’ of the original (as proposed by a post-modern, ‘post-Platonic’ thinker, Jacques Derrida, in his La difference). It does not mean that a theoretical reflection on the status of images accompanied the actual viewing of the Netherlandish images in the fifteenth century, but these terms grasp the illusionistic character of the images of Christ, the Virgin and saints at that time.

In these circumstances, it was necessary for the images to reveal and to highlight their entity as objects – material things, mere simulations of the higher entity (even if, as argued by Baudrillard, this entity was absent). Once again, this observation validates today’s efforts to look at the late medieval images as things.

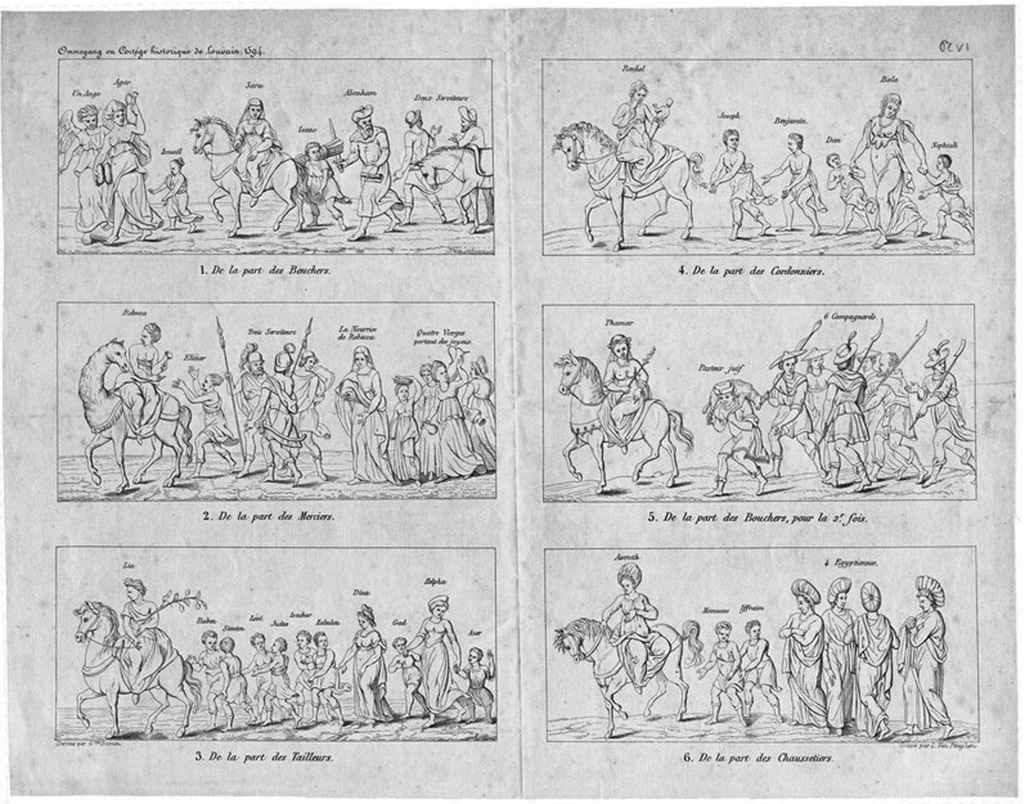

I.3. Multisensory reception of the work of art

Late medieval images, through the illusionism embedded in them, elicited very clear sensory reactions, at times even multisensory, as they stimulated different senses. The Descent from the Cross by Rogier van der Weyden [fig. 52], now in the Prado, engaged not only the sense of sight but also the visual imagination.6 The painting was commissioned for the Chapel ←47 | 48→←48 | 49→of Our Lady Outside the Walls at Leuven, founded in 1364 by the Great Crossbowmen`s Guild to house, from 1365, a venerated figure of the Mother of Sorrows placed on the altar (or alternatively above the altar, or displayed next to it).7 Perhaps Rogier’s painting was intended to replace or complement the carved sacred image. The members of the Guild participated biannually in processions, called ommegangen, to honour the Holy Sacrament and the Virgin Mary [fig. 53]. In the fifteenth century, during the second ommegang (the ancient and honourable tradition dated back to 895), horse wagons carried down the streets of the city living images and theatrical scenes, narrating key episodes from the Life of the Virgin, from the Annunciation to the Assumption.8 Since 1435 the ommegang also included episodes from the life of Christ. Documents from 1435 to 1440 describe platforms with scenes of the Crucifixion, in which a real ←49 | 50→actor, tied to the cross, enacted Christ’s suffering. This means that the members of the Great Crossbowmen’s Guild almost simultaneously, over the course of the same day, saw Rogier’s painting and the scene during the procession. The painted visualisation of The Descent from the Cross with its illusionistic imitation of the Virgin’s suffering and the tormented body of Christ, complemented the “actual” representation of Christ on cross. Since 1437 the re-enactments during the processions included also the Last Supper, the Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane and the Calvary, that is, the Crucifixion witnessed by the Virgin and other attendant figures; it is possible that the performance also included the Descent from the Cross, or the related scenes of the Entombment or the Lamentation. What became important was not the physical presence of the guild’s painting either through its inclusion in the procession, or through the visit to the chapel, but the imaginative, mutual complementing of the ommegangen and Rogier’s painting. Thus, the panel gained new contexts established by representations featuring real actors. Undoubtedly, this enabled a more tangible, sensory experience, which shifted from a simply visual to a haptic and multisensory experience. Moreover, the theatrical representation enabled the spatial experience of the scene, through the tactility, corporeality and movement of the actors. The dramatized Crucifixion and enacted role of the Mother of Sorrows enhanced the painted image with the new suggestion of various experiences. It appealed to the sense of space in its composition, with its illusionistic imitation of the wooden retable; the retable, in which tightly arranged figures hardly fit into the constrained space and seem to step out – or seemingly slip away – towards the viewer, into the real interior of the chapel. Now, through the context of the scenes re-enacted during the processions, the member of the guild mapped the pictorial and quasi-sculptural space onto the actual topography of his town, onto the space known to him, apprehended empirically, temporally and directly. The viewer mentally and imaginatively associated the body of Christ from the painted panel with the physique of the actor, bound to the cross on the procession platform. Consequently, the image appealed more strongly to the sense of touch, the experience of weight and mass. With greater ease the viewer-believer imagined the burden carried by the figures depicted in Rogier’s panel, and could fully engage with the body positioned deliberately in such a way as if the painted protagonists were handing Christ over to the beholder, standing by the altar during the mass. The faithful could take the body as a mystical corpus mysticum Domini Jhesu Christi, present at the Eucharist and distributed during Holy Communion, or as a physical, human body possessing a specific, familiar weight, volume and mass. This, clearly, facilitated the understanding – through visualisation and more importantly through visualised sensation – of the real change of the body ←50 | 51→into bread, the transubstantiation, which constituted the dogmatic meaning of the sacrament. The procession and the image jointly enabled a sensory engagement with the pain of Christ, the Virgin and other participants of the scene: the living actor from the cross suffered, sweated and heavily lowered his head; his body presumably carried painted wounds on his feet, hands and side, which in turn were so veristically depicted by Rogier. Similarly, the tears shed by the Virgin, Mary Magdalene and other figures acted as a reminder of the tears of those participating in the spectacles held during the procession. Perhaps this recent, directly experienced painful memory did not encourage the beholders to automatically and inevitably cry in front of the panel. During the procession the crowd inhaled various urban scents, including the participants’ own bodily odour. The streets carried the discernible and distinct smells of sweat and blood, palpable, presumably, among the acting figures as well as among the members of the guild assembled in the chapel. The sensory experience of the procession complemented, or even filled, the painted composition with sounds – desperate voices, laments, cries, or their absence – silence and daunting stillness. In other words, the theatrical image established during the procession,spectacle or tableau vivant, enlivened and nourished the painterly image, allowing it to engage various senses; not only sight, but also touch, smell and sound.

The late medieval image (be it a painted panel or a figure) was itself mobile or aimed at animating the viewer; it activated the entire sensorium; through encouraging the experience of specific space, weight, mass and volume; it encouraged manual manipulation. It was an active agent (agens, agent-actor according to Bruno Latour), a thing actively exhorting its power on people, their actions, rituals and customs; it was engaged in creating social ties, a network of the interdependencies of civilisation and nature. Nowadays, this active role of the image has disappeared through the process of museumization. Image-things have ceased to be independent objects, becoming works of art entrapped by their role of exhibits, something that only expresses (exhibits) the subjective, extra-material: ideology, religion, aesthetics. It does not constitute, it only expresses. Thus, art renounced its objects, which is not only non-material but also preposterous. Therefore, let us reconstruct in this book an historic active role of things, late medieval and early modern objects of art.

Details

- Pages

- 1032

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631841402

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631841594

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631841600

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631821237

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17833

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (April)

- Keywords

- Netherlandish Painting Middle Ages German Sculpture Medieval Printmaking Medieval Bookmaking medieval tapestries

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2021. 1032 pp., 606 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG