To the Next Station

Papers on Culture and Digital Communication

Summary

This collection of articles discusses social and economic dynamics of digital and technological upheaval. Each contributor approaches the issue from a different frame of reference: translation, advertising, big data and memory, new uses and practices in mass media, effects on journalism, education and free time.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Foreword

- Contents

- Introduction: What is the use of Culture and Communication research? Does it help the less fortunate? Does it release the more able? (Benigno Fernández Salgado / María José Corvo Sánchez)

- 1. Communication, Translation, Globalisation

- ‘Bread’ refuses to be translated. Thoughts on the meaning of Translation (Helena Cortés Gabaudan)

- Hot topics in the new media: Professionals, amateurs, fans and copyright (Tomás Costal / Lourdes Lorenzo)

- Technological cleavages: Flows and cultural representations by the new generations (Josefa Piñeiro Castro)

- The Production of Structuralist Space – The Philosophy behind the Aesthetics of the City of Culture in Santiago de Compostela (Tina Poethe)

- 2. Internet, Advertising, Social Media

- Recommendation algorithms in social media: Beyond human communication (Xabier Martínez-Rolán)

- The impact of (standard vs expert) Facebook friends’ credibility on the audio-visual consumption (Verónica Crespo-Pereira / Pilar García-Soidán / Valentín-Alejandro Martínez-Fernández)

- A journey in time: Retrobranding in the food sector in Galicia at the beginning of the 21st century (Tania Sueiro Graña)

- Spanish universities’ MOOCs and the use of multimedia teasers to attract students (Joana Querido Gomes)

- Big Data and data mining: Opinion mining in the field of microblogging on Twitter. State of the art and new trends (Joan Miquel-Vergés)

- 3. Education, Leisure, Literature

- From the classroom to the wall: The adolescent vision of the myth of romantic love in participatory street art (Lorena Arévalo Iglesias)

- Going to the park or staying in: What activities do Galician children spend their free time on? Analysis of the routines that minors consider preferential in their lives (Beatriz Feijoo)

- Literature, postmemory and blog: A new avenue for writings about the self and for a transatlantic perspective. Spain in Diario de una Princesa Montonera – 110% Verdad (Mariela Sánchez)

This book contains explorations of what we humans are doing at the outset of the third millennium – of the culture of the present moment – and of how we communicate in order to achieve what we set out to do. The research articles it presents do this in a slightly more specific and localized way: they attempt to show how Galician people understand communication, they deal with the communication techniques and technologies that are available to us, and in several cases they evaluate how we are implementing them in our work. Our publication follows the line of two previous instalments with similar aims, focus and approaches: Comunicar(se) en el siglo XXI (García González & García González, 2014), and Redes y retos (Diaz Fouces & García Soidán (2015).

In the following pages, serving as academic editors and scholars interested in the fields of Culture and Communication Studies, we will try to establish a framework for the contributions of the fifteen researchers that participate in the volume. With the exception of two of them, all of the contributors are researchers who have been linked in one way or another to the university of the south of Galicia. Following Weinberger’s suggestions on rethinking knowledge (2011), our purpose in this introduction is twofold: (i) to reflect on what we have done collectively in relation to Communication Studies, summarizing each contribution, organizing them and providing a context for them; and (ii) to glimpse the space for action that might be interesting to address in future research through the questions featured in the above title.

In the foreword to a recent book, Xosé López García, professor of Communication at the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela (USC), took stock of the state of the art in Communication Studies. In the Spanish context of the last few decades, researchers in the Social Sciences have come a long way, according to this ← 11 | 12 → top scholar in the field of communication studies in the Hispanic world.1 Along this way, which he describes as “complex,” academics from Spanish universities have faced two main challenges. On the one hand, they have tried to gain recognition from the international scientific community, and on the other, to produce work that can be useful and contribute to the advancement of humanity. The congratulatory words that summarize his assessment conclude with praise for an academic job well done, followed by an adversative expression: “the work was done with effort, talent and insight, but also leaving many loose ends” (López García, 2017: 7).

Those “many loose ends” constitute for Manuel Goyanes, the author for whom the foreword was written, the cornerstone of the empirical and, at the same time, deconstructive critique he makes of so-called “standard research.” Ultimately, they also serve him in the third chapter to formulate an alternative, which he advocates as “challenging research.” To his mind, the kind of research he postulates as an alternative should look for more progressive and creative challenges than the obvious pragmatic objective of being published in the most prestigious journals. Even if we accept the effectiveness of “standard research” to achieve academic recognition and job stability, there seems to be no doubt, either for the author of the book (Goyanes, 2017) or for the writer of the foreword, that it is necessary to seek improvements in research and publication protocols and methods in the area of social and communication sciences.

Goyanes’s critique focuses on research as a commodity, as a good or service that can be bought or sold. He has performed empirical analyses of over 223 articles published in scientific journals, and he concludes that the texts he has analysed, even though they follow formulaic forms and precepts, “do not manage to produce challenging results and ideas.” They simply constitute “standard research.”2 Goyanes warns that it would be beneficial to question the legitimate precepts that govern the production of scientific research on communication in order to look more in depth into other visions that might concur with the existing ones. ← 12 | 13 → Only with this attitude would there also be alternatives that could overcome the limitations of the standard models and the mere formalism and strategies of the dominant frameworks.

We cannot predict to what extent this volume will contribute to the challenges welcomed by López and Goyanes, but we can say that, from the initial call for papers to the successive revisions in content and expression of the contributions,3 the editors and researchers had the firm intention and the willingness to question what had already been done. From the starting point of the research proposals outlined, they moved forward by revising the pre-established notions, without giving up any of the formal accuracy demanded by an academic setting. The back and forth process of rereading and correcting some of the texts attests to that determination in the context of the PhD program in Communication, launched four years ago. To what extent they diverge from standard research to provide new knowledge or suggest alternative visions and values is something that the most critical readers must now assess.

Our guidelines, both for the publication of this book and for the previous two collective works we coordinated in the PhD Program,4 largely coincide with the conclusive remarks made by Goyanes (2017: 154–162) regarding what “challenging research” should be achieved. These are: (i) to help to build a project that will bring together and provide coherence to a research school in Vigo (which might be somehow in contrast with the currently dominant Compostela school); (ii) to foster denationalization in the sense of not privileging the nation-state framework and ideology of the 19th and 20th centuries; for example, promoting respect and appreciation for the different national traditions in order to achieve a truly pluralist vision of global culture and research at an international level; and (iii) to interconnect the study of the local and the global, beginning with basic research on communication through languages and their formal and notional variability. Accepting the axiom of equality among all languages and valuing their role in the construction of personal and local identities and in our perception of reality helps to put into perspective the importance and the practicality of research on the “discourses” about culture and communication.5 ← 13 | 14 →

We also share with Goyanes (2017) and with López García (2017) the belief that scientific plurality and diversity are prerequisites for the advancement of science. For this reason, we hope the book will become a melting pot of cultural and communication studies that will contribute to enriching the discussion in the field of research into human relations. Such relations are undoubtedly “social” in nature and “specially complex” at the current time, when individuals must adapt not only to the changing physical and cultural surroundings in which they live, but also to the new realities created by the ever-growing use of technology and the omnipresence of the media in all aspects of human experience. We understand that the issues that arise are truly so complex that addressing them soundly will require, besides collaborative work, the adoption of a far-reaching perspective that we could describe, for lack of a better word, as “ecological.” Within such a framework, we should consider the transversality and effectiveness of the set of multiple intervening factors and be able to assess their pertinence.

In a world which is increasingly interconnected as a result of globalization, the questions that arise both at the local and global levels about the future of humanity and its cultures are considerable. Researching from the Galician perspective provided by our unique cultural situation, we the linguists, the journalists, the philologists, the translators, the students of Communication and Adverting should ask ourselves, first of all, about the role that “cultural communities” play in the development of their media, and how we can help those communities to be and live in the world (Fernández Salgado, 2001). The fact that the economic crisis of 2008 did away with the only two daily newspapers published in Galician, Galicia Hoxe, which disappeared in 2011, and the free paper from the group El Progreso, De Luns a Venres (with 50,000 copies in print at one point) is perhaps indicative of how pertinent it is to do research on local and regional media. Only a few years later, other media in far more widely spoken languages are meeting the same fate.6

At any rate, we should add here that what we mean by “cultural communities” should be understood in the wide sense of the term (West & Turner, 2005: 397–455). It would not include just “national” communities as defined by current states (such as those grouped under one state, like Spain) or “linguistic” communities ← 14 | 15 → (like the Galician community), but any other type of human association where people share common elements or interests in their material or spiritual day-to-day lives. Small local communities, the communities of enthusiasts, amateurs or professionals that the web will foster more and more, or the international scientific community, would be “communities” of culture that might be studied and analysed fruitfully from the unique position of our university. In fact, researching what happens when we communicate with people who come from other cultural traditions and have different expectations would undoubtedly be a challenge worthy of our times: managing human diversity.

It is true that widely diverse issues may arise when we address such a vast and hazily defined field as the one we have just suggested. There are issues relating to the access and dissemination of information. A large number of the articles included touch on this topic from different angles: the role of the individual, citizens, corporations and the different administrations in the management of information and knowledge; the role of the state as a neutral mediator and its transparency; the role of technological companies and the use of technology in innovation and the development of new projects; the individual’s right to privacy and the user’s right to free speech; the changes that institutions and corporations will be forced to implement, etc. etc. Although some of these topics might not have been among the interests of the researchers that voluntarily offered to participate in this volume, there are many aspects of them that do appear in the pages that follow, and some of their ideas and the stated facts might help to address some of the issues we have just listed. That is, at least, our hope.

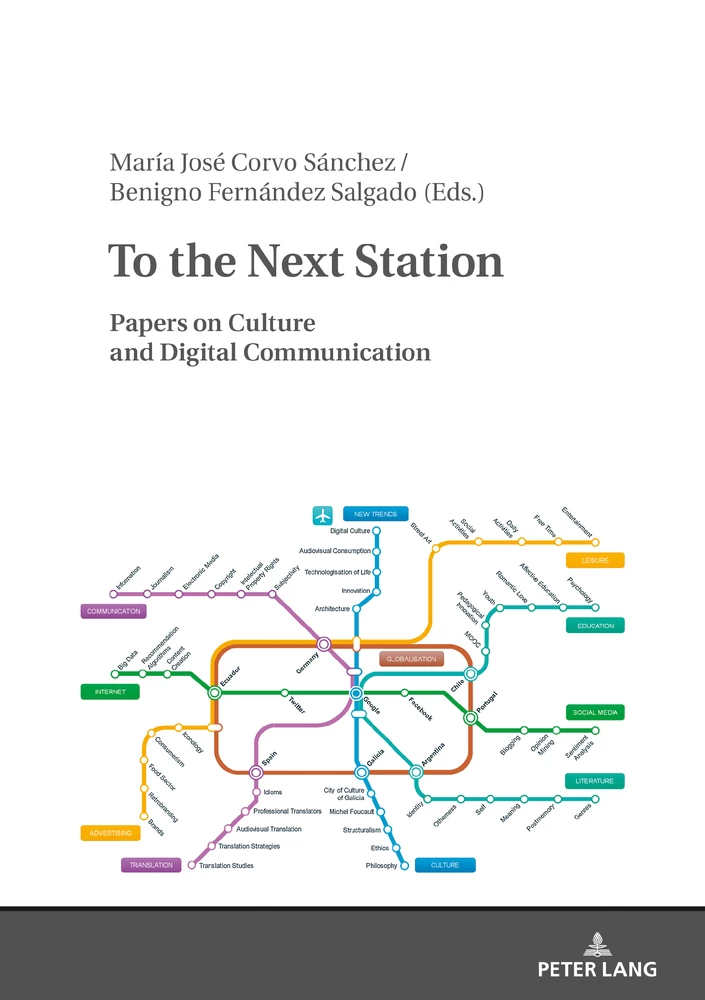

In the paragraphs below we will provide a brief summary of the three sections in which the volume is divided and of each of the contributions included in them, together with brief personal notes about the authors and what struck us about their articles. In terms of contents, this information is shown graphically in the following illustration (see next page). Our subway map attempts to represent some of the themes and keywords this book deals with. Its only aim is to encourage the reader to explore the articles of this volume.

The first section is composed of four contributions regarding communication, translation and globalization. In many senses, translation could be understood as a kind of paradigm of what communication is. Globalization, on the other hand, seems to refer to a wider concept. In a way, it is the epitome of modern times, the result of the free flow of communication and transfers worldwide. But these transfers are so diverse and of such a different kind in terms of the movement of goods, capital, services, people, technology and information that it would involve at least three significant areas or dimensions – economic, cultural and political – which ← 15 | 16 → are not easy to handle for just one person. Observing how the international integration of countries, economies and communications arises from the exchange of world views, ideas, languages, products or other aspects of culture seems to us, in itself, a fascinating task, well worthy of study.

The first contribution included comes from the field of the humanities. It is brought to us by Helena Cortés, from the German department of the Faculty of Philology and Translation of the University of Vigo, where she combines teaching German language and literature with research on translation. As a philosophical and discursive tone pervades her work, we thought it might function as an introduction to the scope and limits of human communication, taking as a starting point the illustrative example of the translation of an apparently simple word, pan (“bread”). As the reflection it is intended to be, it places us at the heart of the problem of what it means to communicate, using the practical exercise of “translation” metonymically. Her inspiration, as she herself points out, is drawn from the brief but famous text by Walter Benjamin The Task of the Translator (1923), although her approach is more radical, closer to the belief that the lack of understanding (or misunderstanding) is a key element of communication. Benjamin mentions in his essay that the German word for bread, Brot, and the French word, pain, refer in a very different way to the same concept, but the author makes an even more radical postulate, suggesting that it might be possible to claim that they do not even refer to the same concept. The simple case of “pan” might be the best example of the explicative paradigm for why perfect or total translation is, in fact, impossible, since, ultimately, human communication is far from perfect and, to a certain extent, erroneous. ← 16 | 17 →

Figure 1: Metro map showing themes, keywords and countries.

Details

- Pages

- 242

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631713525

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631721667

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631721674

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631721681

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11063

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (December)

- Keywords

- Translation Globalisation Internet Social Media Leisure Literature

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2018. 241 pp., 55 fig. b/w, 15 tables

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG