Shaping International Public Opinion

A Model for Nation Branding and Public Diplomacy

Summary

Each chapter applies the Model of Country Concept across a wide geographic, methodological, and disciplinary range of qualitative and quantitative research studies. They include traditional and social media content, international educational exchange programs, tourism, government-sponsored programs, and entertainment. By way of definitions, prior research findings, professional best practices, and published theories and models, the book offers a framework for future positioning of both practice around and research about nation branding and public diplomacy.

Written for practitioners, researchers, teachers, and students of public diplomacy, international relations, media/journalism, and strategic communication, among others, the book offers a comprehensive yet approachable solution for framing a conversation about the heterodox nature of nation branding and public diplomacy, and advances the field through original research.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword (Guy J. Golan)

- References

- Chapter One: Introduction (Jami A. Fullerton)

- References

- Chapter Two: The Model of Country Concept Explained (Jami A. Fullerton / Alice Kendrick)

- Overview

- Structure and Overview

- Agents

- Research

- External Environments

- Disasters

- Global Media

- International Politics

- Cultural/Historical Relationships

- Economic Conditions

- Technology

- Country Concept

- Nation Branding

- Integrants of Nation Branding

- Public Diplomacy

- The Integrated Model of Public Diplomacy

- Micro-Model of Public Diplomacy

- Conclusion

- References

- Part One: Country Concept

- Chapter Three: A Historical Overview and Future Directions in the Conceptualization of Country Images (Michael Elasmar / Jacob Groshek)

- Overview

- The Cognitive Concept of “Image”

- The Impetus for Studying Country Images: Unesco Tensions Project

- Country Images and the Adjacency of Multinational Corporations

- Country Images and the Maturation and Global Reach of News

- Country Images and the 9/11 Terrorist Attacks on the United States

- Pathways Forward in Theorizing and Contextualizing Country Images

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Four: Trust in Nation Branding and Public Diplomacy: Beyond Reputation and Image (Claudia Labarca)

- Overview

- Introduction

- Place of Trust in Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding

- Part 1: Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding: Contested Scope and Conceptualizations

- Part 2: The Model of Country Concept and the Need to Incorporate Trust into Its Definition

- Part 3: Trust as an Interdisciplinary Concept

- How Trust is Built: a Theoretical Review

- Sources of Trust

- Governance and Trust

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Five: The Role of Familiarity in Shaping Country Reputation (Dane Kiambi)

- Overview

- Ghana: Challenges and Opportunities

- Opportunities for strategic communication and reputation management

- Country Reputation

- Direct and Indirect Experiences

- Familiarity

- The Study

- Hypotheses

- Sample

- Measures

- Dimensions of sub-Saharan African countries’ reputation scale

- Security appeal

- People appeal

- Sports appeal

- Emotional appeal

- Physical appeal

- Financial/economic appeal

- Leadership appeal

- Cultural appeal

- Social/global appeal

- Political appeal

- Instrument for measuring direct experiences

- Instrument for measuring indirect experiences

- Instrument for measuring familiarity

- Instrument for measuring supportive intentions

- Results

- Discussion

- Familiarity as a Mediating Variable

- Implications for Nation Branding and Public Diplomacy Practice and Theory

- References

- Chapter Six: A Sample Methodology for Extracting and Interpreting Country Concept from Social Media Users and Content (Jacob Groshek / Lei Guo / Chelsea Cutino / Michael Elasmar)

- Overview

- New Opportunities for Extracting Country Concept

- Research Questions

- Method

- Findings

- RQ1: Users

- RQ2: Topics

- Discussion

- Research Limitations

- Conclusion

- References

- Part Two: Nation Branding

- Chapter Seven: Ferguson, Global Media Narratives, and Nation Branding (Ibrahim N. Abusharif)

- Overview

- Introduction

- The Emergence of an Internationalized Ferguson Narrative

- Ferguson and Arab World References

- Ferguson compared with the Arab Spring

- Ferguson and the “Spring” descriptor

- The role of social media

- The “Ferguson-Palestine” connection

- Foreign Appropriation of Ferguson

- Autocratic states

- Egypt

- Iran

- Gaza

- Conclusion

- Note

- References

- Chapter Eight: Movies’ Influence on Country Concept (Fang Yang / Bruce Vanden Bergh)

- Overview

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Place Branding, Nation Branding, and Public Diplomacy

- Location as Product Placed in Movies

- The Transformation Effect

- Transportation Theory

- Movie Transportation

- Violence in Movies

- Important Questions for Nation-Branding Agents

- The Affective Conditioning Hypothesis

- The Transportation Hypothesis

- Which Hypothesis Is Better Supported?

- Experimental Investigation

- Findings

- Affective Conditioning Effect Is Supported

- The Transportation Effect Is Supported

- So, Which Effect Is Stronger in the End?

- Practical Implications for Nation Branding and Public Diplomacy

- References

- Chapter Nine: Country of Origin, Country Image, and Wine (Fang Liu / Jamie Murphy / Jing Li)

- Overview

- Country of Origin

- Country of Origin and Country Image

- Consumer Ethnocentrism and Product Knowledge

- Research Background

- Conceptual Development

- Research Method

- Design and Measures

- Sample Selection

- Analyses and Findings

- Construct Testing

- Hypotheses Testing

- Conclusion and Discussion

- References

- Chapter Ten: From “Bottomless Basket” to “Beautiful Bangladesh”: Nation Branding through Tourism and Public Diplomacy (Imran Hasnat / Elanie Steyn)

- Overview

- Introduction

- Tourism Advertising as an Integrant of Country Concept

- Bleed-over Effect of Tourism Advertising

- Mediated Public Diplomacy and Tourism Advertising

- Case Study: “Beautiful Bangladesh”

- The Tourism Industry in Bangladesh

- “Beautiful Bangladesh” Campaign: School of Life

- “Beautiful Bangladesh” Campaign: Land of Stories

- Discussion and Conclusions

- References

- Part Three: Public Diplomacy

- Chapter Eleven: Impact and Evaluation of International Exchange Programs as Tools of Relational Diplomacy (Mallorie Rodak)

- Overview

- Part I: The Spectrum of Relational Diplomacy

- International Exchange Programs in Relational Diplomacy

- Relational public diplomacy

- Relational citizen diplomacy

- Models of Relational Diplomacy

- Spectrum of Relational Diplomacy Model

- Relational Public Diplomacy: Types

- Relational Citizen Diplomacy: Types

- International Exchanges as a Component of Nation Branding

- Part II: The Impact of International Exchange Programs

- Individual and Multiplier Effects of International Exchanges

- Developmental and Intercultural Theory

- Intercultural Competence and the Model of Country Concept

- Limitations of Measurement

- The Immersion Assumption

- Paradigms of Intercultural Development Gains

- Discussion

- Further Research and Limitations

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Alternate Measures of Intercultural Competence

- References

- Chapter Twelve: Factors Shaping U.S. College Students’ Concept of China and Willingness to Study in China (Olga Zatepilina-Monacell / Hongwei “Chris” Yang / Yingqi Wang)

- Overview

- China’s Public Diplomacy, Nation Branding, and Educational Exchanges

- The Construct of Country Reputation

- Educational Exchanges in the Public Diplomacy and Nation-Branding Contexts

- Our Study

- Our Findings and Implications for China’s Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding

- References

- Chapter Thirteen: The U.S. Secretary of State’s Award for Corporate Excellence: An Intersection of Nation Branding, Public Diplomacy, and Global Corporate Social Responsibility (Janis Teruggi Page / Lawrence Parnell)

- Overview

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

- CSR as Brand Exports

- The Reputation-Building Influence of CSR

- The “Halo Effect” of CSR

- CSR and Other Influences on Country Reputation

- Nation Branding, Public Diplomacy, and CSR

- The Award for Corporate Excellence (ACE)

- ACE “Good Works”

- The Case of ACE, 2010–2014

- 2014 ACE Winners

- 2013 ACE Winners

- 2012 ACE Winners

- 2011 ACE Winners

- 2010 ACE Winners

- Impact of ACE Winners

- ACE Media Efforts

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- References

- Chapter Fourteen: A Propaganda Analysis of the Brand USA Tourism Campaign: Government-Sponsored Advertising to International Travelers (Jami A. Fullerton / Alice Kendrick / Mallorie Rodak)

- Overview

- Propaganda as Paid Mediated Public Diplomacy

- Propaganda Defined

- Brand USA as Propaganda

- Purpose and Method

- Description of the Brand USA Campaign

- 10-Step Analysis

- 1. Ideology and Purpose of the Propaganda Campaign

- 2. Context in Which the Propaganda Occurs

- 3. Identification of the Propagandist

- 4. Structure of the Propaganda Organization

- 5. Target Audience

- 6. Media Utilization Techniques

- 7. Special Techniques to Maximize Effect

- 8. Audience Reaction to Various Techniques

- 9. Counter-propaganda

- 10. Effects and Evaluation

- Limitations and Further Research

- Conclusion

- References

- Contributors

- Editors

- Authors

- Index

Partial funding for the creation of this book came from grants from the following:

• Center on Public Diplomacy at the University of Southern California

• Temerlin Advertising Institute at Southern Methodist University

• Peggy Layman Welch Chair in Strategic Communications at Oklahoma State University

Special thanks to our dedicated copyeditors and former students of Dr. Fullerton’s, Josh Danker-Dake and Olga Randolph.

To the graphic designer and Web editor at OSU-Tulsa, Ryan Jensen and Jamie Edford.

And to Simon Anholt and Guy Golan for their intellectual contributions to nation branding and public diplomacy and for speaking at the August 2015 symposium in San Francisco that formed the basis for this book.

We dedicate this book to our daughters—Helen and Sara.

In past decades, public diplomacy emerged as a growing area of academic scholarship. Multidisciplinary in nature, public diplomacy draws upon literature from international relations, mass communications, peace studies, law, and political science. Breaking across academic silos, the field enjoys many advantages, while at the same time facing key challenges. Chief among these challenges is the lack of theoretical underpinnings unique to the discipline. Public diplomacy scholars approach key questions relevant to the field of study from a variety of disciplinary perspectives. This allows for intellectual multiplicity and a diversity of voices. On the other hand, the multidisciplinary nature of the field often causes confusion regarding basic definitions, assumptions, and, in many instances, the very purpose of public diplomacy scholarship.

A review of decades of public diplomacy literature indicates that Nye’s concept of soft power (1990) is ever present in the field’s literature. Nye argued that a nation’s soft power may help secure the support of foreign publics for its foreign policy by means of the attractiveness of its culture, political values, and foreign policy. Nye would later argue (2004) that a nation’s soft power, combined with hard power, can produce smart power.

As reflected in the growing body of public diplomacy scholarship, dozens of studies examine a wide variety of governmental and non-governmental programs focused on soft power promotion. In what I refer to as the fill-in-the-blanks diplomacy approach (see Golan, 2014), scholars have focused on such soft power ← ix | x → programs and tactics as food diplomacy, music diplomacy, gastro-diplomacy, water diplomacy, exchange diplomacy, sports diplomacy, dance diplomacy, and others.

While many scholars argue for the long-term benefits of such relationship-building soft power programs, others have criticized soft power as a normative concept that is often presented as a key function of public diplomacy, but that fails to show direct outcomes in terms of international public support for foreign policy (see Roselle, Miskimmon, & O’Loughlin, 2014). Furthermore, while soft power is an interesting concept, it fails to provide scholars with the predictive capabilities of a social scientific theory.

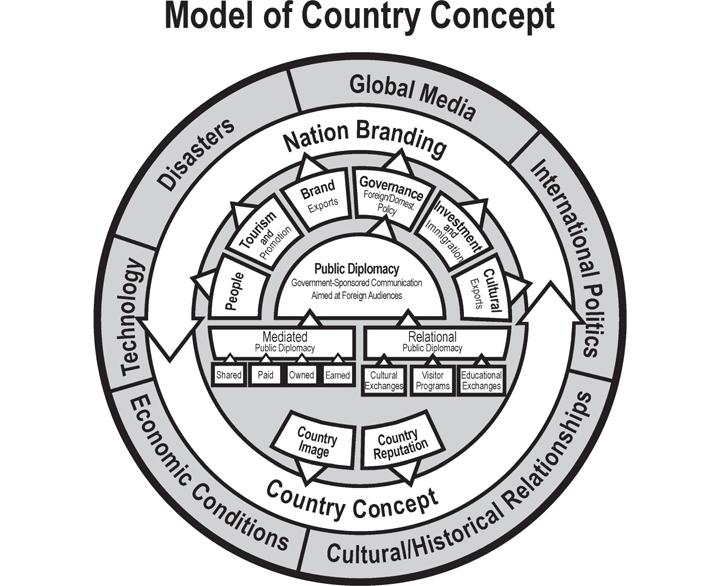

Over the course of the past two decades, several public diplomacy researchers have presented a variety of models and taxonomies that aim to clear the confusion regarding such key concepts as government-sponsored broadcasting, nation branding, country reputation, foreign public opinion, and their relationship to one another in the context of public diplomacy as an academic discipline (see Entman, 2008; Gilboa, 2008; Cull, 2008; and Golan, 2014). The current volume builds upon previous public diplomacy studies and provides scholars and practitioners a new framework as well as guidance regarding the interrelationship among key concepts through the presentation and application of the Model of Country Concept.

REFERENCES

Cull, N. J. (2008). Public diplomacy: Taxonomies and histories. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 31–54.

Entman, R. M. (2008). Theorizing mediated public diplomacy: The US case. International Journal of Press/Politics, 13(2), 87–102.

Gilboa, E. (2008). Searching for a theory of public diplomacy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 55–77.

Golan, G. J. (2014). An integrated approach to public diplomacy. In G. J. Golan, S. U. Yang, & D. F. Kinsey (Eds.), International public relations and public diplomacy: Communication and engagement (pp. 417–439). New York: Peter Lang.

Nye, J. S. (1990). Soft power. Foreign Policy, 80, 153–171.

Nye, J. S. (2004). Soft power: The means to success in world politics. New York: Public Affairs.

Roselle, L., Miskimmon, A., & O’Loughlin, B. (2014). Strategic narrative: A new means to understand soft power. Media, War & Conflict, 7(1), 70–84.

“The only remaining superpower is international public opinion,” declared policy adviser Simon Anholt in a 2014 TED talk. Both scholars and researchers contend that attitudes held by the international public about other countries are critical to a nation’s security and economic well-being. In this era of globalization understanding how international public opinion is shaped is a critical area of study and practice, yet one that historically has suffered the angst of two competing paradigms—nation branding and public diplomacy.

Researchers and professionals from a variety of disciplines have pursued the practice of both nation branding and public diplomacy, not surprisingly by employing existing discipline-specific theories, models, and terminology to frame their work. A core group of communication scholars, for instance, has developed around the study of public diplomacy as public relations (see, e.g., Golan, Yang, & Kinsey, 2014). Scholars from marketing continue to explore ways in which a country’s image can be managed like a brand (Kotler & Gertner, 2002). While many have written about the overlaps and intersections of nation branding and public diplomacy (see, e.g., Kaneva, 2011; Szondi, 2008), few have attempted to integrate the two fields—and their many related areas—holistically. This book presents a model that attempts to bridge the “two camps” in the field—nation branding and public diplomacy—through its introduction of the Model of Country Concept. The Model of Country Concept is a cohesive framework through which scholars, teachers, practitioners, and students can better research, teach, practice, and understand the field.

For Alice and me, this book results from more than a decade and a half of study, research, and teaching in the field of nation branding and public diplomacy. We began our journey after 9/11 when President George W. Bush asked, “Why do they hate us?” This question intrigued and inspired us to embark on a journey to understand how attitudes toward countries are formed and how they might be changed. We were energized by the period shortly after the 9/11 attacks on the United States when advertising guru Charlotte Beers went to Washington to “re-brand America.” That campaign became the subject of our first book, and we continued our involvement in advertising-as-public-diplomacy when we served on the initial research advisory board for the newly formed Brand USA. In the summer of 2013, a sort of conceptual culmination occurred as the model emerged from our scholarship. We trialed the model through our own data sets, but it was not until others from various fields found it intriguing enough to explore that we were convinced that the Model of Country Concept deserved presentation in book form.

As advertising professors and media effects scholars, the metaphor of a country as a brand has been one that we could easily understand and embrace. However, we recognize that this position has often set us apart from our colleagues who believe that the honorary work of government (public diplomacy) should never be compared to “brash” marketing tactics (nation branding). We don’t hold this view; ← 2 | 3 → instead we try to step outside the stereotypes and traditional paradigms to understand the milieu in which global citizens form impressions of faraway places—notions of nations, if you will—and the factors that might alter or mitigate those views. We believe that, as the world in which we live becomes smaller and smaller, this is worthwhile work, which in turn makes understanding the roots of global opinions all the more critical.

At its core, The Model of Country Concept illustrates the various factors, or integrants, that influence how global citizens shape their opinions about other countries. The model is fully described in Chapter 2. The purpose of this chapter is to provide background, an explanation, and an introduction to the individual chapters that make up the bulk of the text. This edited collection contains 14 chapters written by a combination of 22 authors, including Alice Kendrick and myself. The authors were chosen from among dozens of scholars and practitioners who responded to a call for a symposium on the topic of the Model of Country Concept in the summer of 2015. The selected authors, who cover a wide academic spectrum, contributed essays and empirical research to comment on and test the model. The best papers were presented at a full-day symposium in San Francisco prior to the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication’s national conference. Most of the chapters in this book evolved from those paper presentations. Authors were asked to situate their research on the Model of Country Concept. Therefore, at the beginning of each chapter, the model is featured with the integrants under study in that chapter highlighted.

The first section of the book focuses on the ultimate outcome of the model—Country Concept—and contains four chapters that examine this newly proposed notion in various ways. Because, according to the model, country concept consists of two underlying elements—country reputation and country image—chapters in this section incorporate one or both of these dimensions in their discussion. Chapter 3 provides a much-needed overview of scholarship about country image that goes back to World War II. In this chapter, authors Michael Elasmar and Jacob Groshek explain how history and external forces drove research on country image and how the field waxed and waned over the decades, leading to the most recent flurry of interest in country image that has taken place since the attacks of 9/11. In Chapter 4, Claudia Labarca takes the reader beyond image and reputation as she positions the element of trust as a critical factor in shaping country concept. The final two chapters in this section provide quantitative research that explores country concept. In Chapter 5, Dane Kiambi uses Ghana as a case in which to apply the model and its variables. Kiambi arrives at the factor of familiarity with a country as an important mediating influence. In Chapter 6, Jacob Groshek and co-authors Lei Guo, Chelsea Cutino, and Michael Elasmar introduce a fascinating approach to tease out country concept from big data—in this case millions of Twitter posts about the country of Cuba at a critical time in its history. ← 3 | 4 →

The middle section of the book explores nation branding, its many integrants, and how they influence country concept. Chapter 7 is written by Ibrahim Abusharif, a former journalist who is now a professor in Qatar. Abusharif explores the global media coverage of the 2014 Ferguson, Missouri, shooting of a black man by a white police officer. In the chapter he draws attention to the paradox of beautiful U.S. tourism advertising running on Middle Eastern satellite TV against a backdrop of anti-American news coverage about Ferguson. Abusharif employs this chapter to question the impact of global media on the nation brand of the United States. The remaining chapters in this section explore specific integrants of nation branding, including cultural exports, brand exports, and tourism. In Chapter 8, Fang Yang and Bruce Vanden Bergh examine the influence of movies in shaping country concept by testing college students’ attitudes toward Japan after viewing either a violent film or a non-violent film set in Japan. To explore the impact of country-of-origin effect on country concept, Fang Liu, Jamie Murphy, and Jing Li (Chapter 9) employ an interesting field experiment to measure preference for wines from Australia, France, and China among Chinese consumers. This section concludes with Chapter 10, by Imran Hasnat and Elanie Steyn, who present a nation-branding case about a recent tourism campaign in Bangladesh—a beautiful country that has suffered from a debilitating international image.

The final section of the book contains four chapters on various aspects of public diplomacy. The first two investigate relational public diplomacy. Chapter 11, by Mallorie Rodak, who admirably provides a much-needed taxonomy to classify and evaluate various relational public diplomacy programs, includes cultural exchanges, educational exchanges, and visitor programs. In Chapter 12, Olga Zatepilina-Monacell, Hongwei “Chris” Yang, and Yingqi Wang dissect the influences of country concept on attitudes and intentions toward study-abroad programs in China by U.S. students. The third entry in this section, Chapter 13, by Janis Teruggi Page and Lawrence Parnell, highlights the intersection between public diplomacy and brand exports via the State Department’s Award of Corporate Excellence (ACE). Chapter 14, which concludes the book, was written by Alice Kendrick, Mallorie Rodak, and myself, and chronicles the U.S. public-private partnership known as Brand USA, whose mission is to promote international tourism to the United States and improve America’s image abroad.

Taken together, the chapters both affirm and challenge the Model of Country Concept by providing data-driven research and informed commentary about programs and phenomena that influence how people around the world shape and re-shape their attitudes toward other countries. More important, the chapters provide much fodder for additional research in the field and establish a foundation from which to conduct such research. In editing the book, we have attempted to solidify definitions and clarify concepts in this multi-disciplinary field. ← 4 | 5 →

Shoemaker, Tankard, and LaSorsa (2004) describe a theoretical model as “a tool that can promote theory construction” (p. 107). Gilboa (2008) noted the need for a model of public diplomacy in his paper “Searching for a Theory of Public Diplomacy” when he wrote: “Models are needed to develop knowledge because they focus on the most significant variables and the relationships between them” (p. 3). Through its introduction and explanation of the Model of Country Concept, this book attempts to answer Gilboa’s call, and in doing so creates a blueprint for use in building theory about public diplomacy and country concept. It is through the explanatory power of the model that this book makes its contribution.

REFERENCES

Gilboa, Eytan (2008). Searching for a theory of public diplomacy. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 55–77.

Golan, G. J., Yang, S., & Kinsey, D. F. (2014). International public relations and public diplomacy: Communication and engagement. New York: Peter Lang.

Kaneva, N. (2011). Nation branding: Toward an agenda for critical research. Communication, 5, 117–141.

Details

- Pages

- X, 282

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433130281

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433135736

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433135743

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453918647

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433130298

- DOI

- 10.3726/b10433

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (March)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2017. X, 282 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG