Defining Critical Animal Studies

An Intersectional Social Justice Approach for Liberation

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

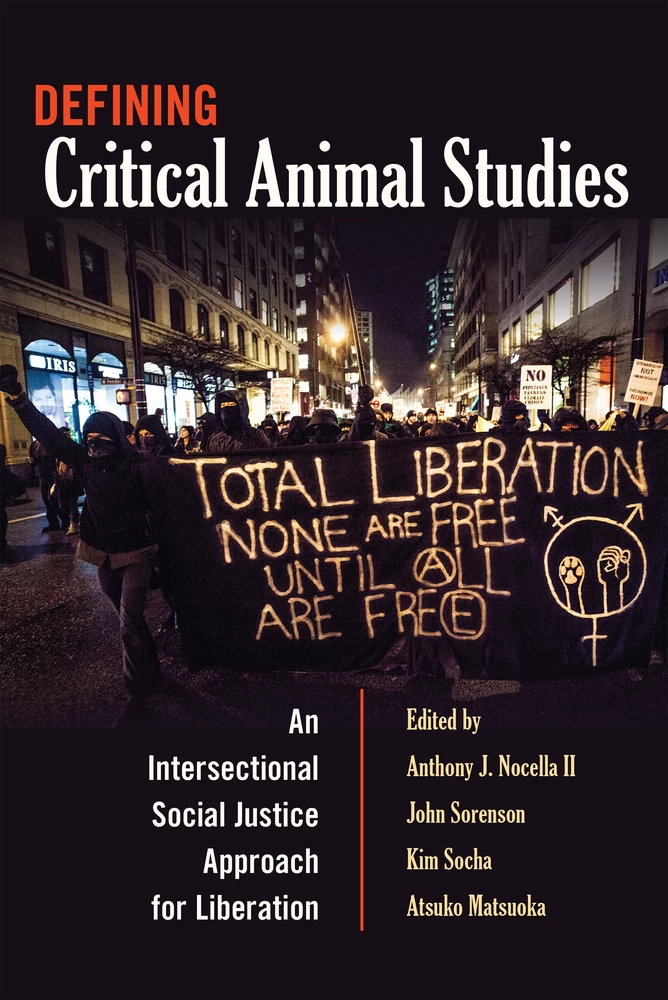

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- Advance praise for Defining Critical Animal Studies

- Dedication

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Foreword: David Nibert

- Preface: Ronnie Lee

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Emergence of Critical Animal Studies: The Rise of Intersectional Animal Liberation: Anthony J. Nocella II, John Sorenson, Kim Socha, and Atsuko Matsuoka

- A Very Brief Historical Overview of Animal Advocacy

- The Emergence of Critical Animal Studies

- The Implementation of Critical Animal Studies

- Philosophical Structure of the Book

- Organization of the Book

- References

- Part I: Interdependency

- 1 An Overview of Anthropocentrism, Humanism, and Speciesism in Critical Animal Theory Adam Weitzenfeld and Melanie Joy

- Anthropocentrism, Humanism, and the Human-Animal Dualism: The Anthropocentric and Anthropocentrism

- Anthropocentrist Humanism and the Human-Animal Dualism

- The Ironies of Anthropocentrist Humanism: The Irrational Dualism and Inhumane Hierarchy

- The Anthropological Machine and Hegemonic Centrisms

- Liberal Humanist, Posthumanist, and Feminist Anti-speciesism: Multiple Theoretical Fronts Against Speciesism

- Anthropocentric Bias and Consistency in Liberal Humanism

- Posthumanist and Feminist Challenges to the Autonomous Humanist Subject

- Rationality, Rule-based Ethics, and the Marginalization of Embodiment and Care

- Universal, Individual-based Ethics, and the Marginalization of Ecology and Dependency

- The Critical Animal Turn: The Theoretical Analysis of and Opposition to Speciesism

- Carnism: A Case Study of Structural Speciesism

- References

- 2 Ecological Defense for Animal Liberation: A Holistic Understanding of the World Amy J. Fitzgerald and David Pellow

- Interlocking Forms of Oppression

- Critical Feminist Theory

- Intersectional-Multiracial Feminism

- Ecofeminism

- Critical Race Theory

- Environmental Justice

- Green Criminology

- Toward Social-Environmental-Species Justice: The Total Liberation Frame

- References

- Part II: Unity

- 3 Until All Are Free: Total Liberation through Revolutionary Decolonization, Groundless Solidarity, and a Relationship Framework Sarat Colling, Sean Parson, and Alessandro Arrigoni

- Toward a Comprehensive Total Liberation: Expanding the Scope of Total Liberation

- Roots of Total Liberation: Franz Fanon and Revolutionary Decolonization

- Building Alliances for Revolutionary Decolonization: Connecting Civil and Animal Rights

- Nuclear Power, Militarism, Capitalism, and Homelessness: From Intersectionality to Groundless Solidarity

- Nonhuman Animals and Self-liberation: Their Agency, Multiplicity, and Subjectivity

- Envisioning Community: The Relationship Framework and Mutual Aid

- Conclusion: Animal Liberation Is Total Liberation! The Green Hill Beagle Liberation

- References

- 4 One Struggle Stephanie Jenkins and Vasile Stănescu

- Anthropocentrism

- Critical Animal Studies as Practice: Engaged Veganism

- Capitalism and the Commodity Fetish

- Interweaving of Oppression: Sexual Violence, Racism, and Speciesism

- Conclusion: Direct Action

- References

- Part III: Critical Scholarship

- 5 The Ivory Trap: Bridging the Gap between Activism and the Academy Carol L. Glasser and Arpan Roy

- Animal Studies

- The Ivory Trap

- Lack of Access

- Pedants and Jargon

- Escaping the Ivory Trap

- The Fallacy of Objectivity

- The Professional Is Political

- Marginalization

- Methodological Hierarchies

- Knowledge for Knowledge’s Sake

- Building Bridges

- Interlocking Oppressions

- Conclusion: Theory in Action

- References

- 6 Critical Animal Studies as an Interdisciplinary Field: A Holistic Approach to Confronting Oppression Kim Socha and Les Mitchell

- Interdisciplinarity as a Forgotten Life Praxis

- Defining Interdisciplinarity

- Scholars Crossing Borders

- Multifaceted Problems I: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Rhinoceros Poaching

- Multifaceted Problems II: Interdisciplinary and Literary Applications of CAS and CAP

- Activist Outreach with Critical Animal Studies

- 1. The first is titled “Alice Walker ‘Am I Blue?’ Lesson Plan”:

- 2. The next lesson plan was offered to social studies, history and/or civics instructors, titled “Post–Civil War Lesson/Assignment Plan: An Exploration of Justice Movements in the United States”:

- Academic Outreach with Critical Animal Studies

- Conclusion

- References

- Part IV: Radical Education

- 7 Radical Humility: Toward a More Holistic Critical Animal Studies Pedagogy Lauren Corman and Tereza Vandrovcová

- Voice and Dialogue

- Humility and Listening

- Presence and Pain

- Enacting CAS Pedagogy

- The Importance of Context

- Bringing Nonhuman Animals into the Conversation

- Intersectionality of Oppressions

- Working with Graphic Images

- Incorporating Activism

- Conclusion

- Special Thanks

- References

- 8 Engaged Activist Research: Challenging Apolitical Objectivity Lara Drew and Nik Taylor

- Introduction

- CAS, Neutrality, and Ethics

- Research as Resistance

- References

- Part V: Taking It to the Streets

- 9 From the Classroom to the Slaughterhouse: Animal Liberation by Any Means Necessary Jennifer Grubbs and Michael Loadenthal

- Reflexivity: Examining Our Roles as Authors

- CAS Principle 9 and the Role of Academia

- Creating False Binaries: Activist v. Terrorist

- The Privilege of Confronting Speciesism

- The ALF and Its Press Office

- Academic Capitalism: Compulsory Speciesist Thought

- Examining Our Own Marginalized Histories

- Conclusion

- Atop an Activist-Academic Soapbox: A Communiqué of Sorts

- Note

- References

- 10 Taking it to the Streets: Challenging Systems of Domination from Below Richard J. White and Erika Cudworth

- Critical Animal Studies, Anarchism, and Human-scale Resistance

- Anarchism and Domination

- Anarchism and the Nonhuman in Kropotkin and Reclus

- “Is it Vegan?”: Intersectionality, Feminist Politics, and Everyday Life as Models for Liberation

- Challenging Systems of Domination by Becoming Beautiful

- Conclusions: Becoming Beautiful, Becoming Active

- References

- Afterword: From Animal Oppression to Animal Liberation: A Historical Reflection and the Growth of Critical Animal Studies: Karen Davis

- References

- List of Contributors

- Index

- Series index

← VIII | IX →  FOREWORD

FOREWORD

The oppression of humans and other animals always has been deeply entangled. When humans began routinely to hunt large animals—primarily a male pursuit—they could do so only by creating weapons. Those who were most successful at such killing exerted growing power; social hierarchy began to emerge and the status of women began to decline.

The beginning of systemic human exploitation and social stratification can be traced to the advent of agricultural society roughly 10,000 years ago. Agricultural systems were tied to the exploitation of large social animals—including cows, horses, sheep, pigs, and goats—who were captured and exploited as laborers and for their hair, skin, body fluids, and flesh. The possession of large numbers of these other animals became a sign of wealth and dominance, and elite males’ treatment of them as property was extended to women and devalued people. Countless people were relegated to the socially constructed position of peasant, serf, and slave. Growing numbers of men on the backs of horses, armed with weapons—originally created for killing other animals—were dispatched by elites to raid other peoples for their captive animals and other sources of wealth.

Some societies relied almost entirely on animal exploitation for subsistence, such as the patriarchal and highly aggressive nomadic pastoralists of the Eurasian steppe. They rampaged across the continent for centuries in search of the fresh grazing land and water needed to sustain enormous numbers of captive, exploited animals. Invasions led by such murderous men as Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan destroyed countless communities and entire societies; people not murdered by nomadic warriors or forced into slavery died from deadly zoonotic diseases such as smallpox, which had developed from the crowding together of large numbers of other animals. Sexual violence against women became a standard military practice, and countless women were enslaved by elite warriors. Rulers of autocratic empires—empires made possible only by the exploitation of animals as laborers, rations, and instruments of war—invaded weaker societies while battling each other for supremacy. Eurasian customs and institutions, debauched by incessant and widespread violence that was both promoted and enabled by animal ← IX | X → oppression, were spread through imperialism and soon overwhelmed the rest of the world.

Using horses as instruments of war and the salted flesh of other animals as rations, aggressive European elites dispatched their minions to ravage the Earth in search of wealth—much of which was in the form of the skins, hair, body fat, and tusks of other animals and the land and water needed to expand profitable ranching operations. Countless indigenous people in the Americas, Africa, Australia, and other regions were murdered, enslaved, or displaced while others perished from the zoonotic disease brought by the invaders. The destructive invasions relied on state power, and the carnage was rationalized by the use of racism, sexism, speciesism, and other reprehensible ideologies. The resulting ill-gotten wealth allowed the rise of capitalism, a system birthed and continually nourished by the bloody, entangled oppression of the great mass of humans and other animals.

The predacious nature of human society at the start of the twentieth century would have been quite recognizable to Genghis Khan. Adhering to patriarchal and aggressive worldviews cultivated by centuries of violence linked to the oppression of other animals, elites in powerful capitalist nations conscripted millions of people to slaughter each other in wars over resources and markets. While horses no longer were indispensable for warfare after World War I, the flesh of other animals continued to be viewed as essential rations for “fighting men.”

By the mid-twentieth century, the expansion of the oppression of other animals as food through the Animal Industrial Complex (AIC), and the convergence and growth of the Military Industrial Complex (MIC) began to generate enormous profits. The MIC and the AIC became mutually reinforcing systems of domination—continuing the inextricable link between the oppression of other animals and human violence that plagued the history of the world.

For example, financial and military support and intervention provided by the MIC has been used to expropriate enormous areas of land in Latin America for ranching and feed-grain operations and to secure the blood-stained oil on which the AIC remains so dependent. And the AIC, broadly defined, has provided military forces with publicly subsidized rations of animal flesh and endless supplies of other animals for use in military experiments. It supports continued recreational hunting and individual access to deadly weaponry, which complement the agenda of the vast armaments industry.

Now in the twenty-first century, as the destructive trajectory of capitalism is leading to hyper-predatory practices, the rolling back of modest social reforms, and the normalization of state surveillance and repression, the AIC is striving to profitably double the consumption of animal products globally by midcentury. To that end, dwindling vital resources such as fresh water, topsoil, and fossil fuel, all crucial for supporting a growing world human population, are being massively squandered. Moreover, raising other animals for food is responsible for as much as ← X | XI → 51 percent of anthropic greenhouse gas emissions. Global warming already is producing violent storms, floods, severe droughts, wildfires, and record temperatures, all of which reduce harvests and make future food shortages all but certain. While hedge funds, global corporations, and other investors in the AIC are partaking in land grabs, appropriating tens of millions of acres in Africa and Latin America for future ranching and feed-grain ventures, the MIC and entrenched “national security” advisors are planning a military response to a future of scarce resources, food shortages, and global violence.

Forestalling such a calamitous future will require a greater awareness of the historically destructive—and future-threatening—nature of the entangled oppression of humans and other animals. The growing field of Critical Animal Studies (CAS) stands as the only area of study that promotes scholarly examination of entangled oppression of humans and other animals; places this investigation in the context of historical and social structural forces; recognizes the role of capitalism in promoting systemic oppression of all types; and proposes strategies for purposeful action. This highly important book, and the works of CAS scholars and activists to come, will be essential reading for social justice advocates of all stripes and for concerned people everywhere. It is only through the coordinated efforts of everyone throughout the world who is opposed to oppression in any form that capitalism, the AIC, the MIC, and all profit-driven systems of domination can be transcended and a more socially just, sustainable, and peaceful future can develop. ← XI | XII →

← XII | XIII →  PREFACE

PREFACE

Congratulations to Anthony, John, Kim, and Atsuko for producing this excellent work and to all the other outstanding contributors, too.

My involvement in the animal liberation movement has been a long one, more than 40 years to date, and I have experienced much in that time. I think it is vitally important that we learn from our experiences of life and of human behaviour and I have tried to do that, in a continuous quest to become a better advocate for animal liberation. After becoming a vegetarian at the age of nineteen and a vegan two years later, I turned very quickly to direct action, first with the hunt saboteurs and then with the Animal Liberation Front (ALF), as a founder member, which resulted in me spending a total of about nine years in prison for “crimes” against the industries of animal abuse.

On release from my third prison sentence in 1992, I embarked on a campaign of public education, setting up street stalls, often several times a week, to educate people to go vegan and oppose all the various forms of animal persecution. Five years later, my wife, Louise, founded a national campaign against the greyhound racing industry and I became more and more involved with this as it attracted increasing interest and support.

In 2011 the administration of the greyhound campaign was taken on by others, leaving me free to become much more involved in vegan outreach, which I had wanted to do for quite some time. I now help run both a county and a local vegan outreach group and was recently one of the founders of the Encouraging Vegan Education network, which exists to help with the setting up and effective operation of vegan outreach groups. I am also an active member of the Green Party, both locally and nationally, where I am involved in a group that works to improve the party’s animal protection policies.

Although it is my belief that ALF actions have contributed significantly to a huge reduction in the fur trade and a big decline in animal experiments here ← XIII | XIV → in the UK, I now have doubts as to the value of this type of activity in terms of bringing about widespread animal liberation.

For a start, if direct action was ever to reach a scale or an intensity these days where it posed a real threat to the most powerful animal abuse industries, the state would move very quickly to crush those groups and individuals involved—and this is provided only if enough individuals became involved to bring direct action to such a high level, which I feel is extremely unlikely given the intrinsic passivity of most people, including those who are opposed to animal abuse.

Therefore, the only way in which widespread animal liberation, or anything approaching it, can be achieved, is by changing the behaviour of ordinary people towards animals. This means first, vegan education, to attempt to alter the attitudes of a very large percentage of the population, and, second, legislation, to force those who refuse to change to comply. Hence my involvement both in vegan outreach and political campaigning.

My early years in the struggle for animal liberation were spent with a movement that did not engage with the public, but sought to bypass them in its direct war against animal abusers. I now recognise the limitations of this approach, as engagement with ordinary people counts for everything if we are to radically change their attitudes towards other animals. And engagement with ordinary people also means engagement in the struggle for a fair and just society for human beings, as well as for other animals. This is, of course, the moral thing to do in any event, but it is also essential for the achievement of animal liberation, because our movement cannot bring in a political regime sympathetic to the cause of the oppressed on its own, but only in conjunction with other groups that are campaigning against oppression. Public education can take many forms: street stalls, stalls at community events, free food fairs, film shows, talks at schools and colleges, letters in local newspapers, and so on, and it’s important that local vegan outreach groups are involved in all of these. Campaigning to change the existing education system is also important so that we can bring about a situation where students are no longer taught vivisection and farming practices that result in the suffering and slaughter of animals.

Local vegan outreach groups should, in my view, give support to and make allegiances with other local groups campaigning against discrimination and oppression. For instance, the local group I help to run recently took part in a Gay Pride march, and we are involved with our local Green Party and other groups in campaigns to protect the environment, against racism, and in opposition to government and local authority cuts that would harm vulnerable people.

We in the animal liberation movement also need to show more love, care, and respect for one another and to try to find compromise and understanding in those few small areas where we might not all agree on everything. There have been far too many instances of vegans tearing one another’s throats out over what amounts ← XIV | XV → to only minor differences of opinion in the overall scheme of things, and this causes deep wounds that are tremendously damaging to our movement.

Finally, please remember that it is not enough just to read this book, because no matter how eloquent the words contained in it or how persuasive the arguments, these things amount to very little unless they result in an increase in our efforts to get out in the world and to campaign and educate for animal liberation. ← XV | XVI →

← XVI | XVII →  ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are honored and excited to publish the first book on the foundational principles of Critical Animal Studies (CAS), which lays out the history and theory of this important field. We hope this book aids in the growth of CAS to become a truly global academic-activist resistance force against all forms of oppression, especially speciesism. We first and foremost thank the Earth for allowing us a home with so much beauty. We would next like to thank our families. Thank you to everyone at Peter Lang, especially Chris Myers, Stephen Mazur, Sophie Appel, and Bernadette Shade, for all their hard work and for believing in this project. We also would like to thank Shirley Steinberg, the Series Editor of Counterpoints: Studies in the Postmodern Theory of Education, who believed in this project and wanted to publish this book in her series. We are so grateful for the passionate collaboration and outstanding, radical work of each of the contributors to this collection. Finally, we thank those who reviewed this book: Jason Del Gandio, David Gabbard, Julie Andrzejewski, Dan Featherston, Piers Beirne, Leslie James Pickering, Erin Marcus, and Jessica Ison. ← XVII | XVIII →

Details

- Pages

- XXXVI, 241

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433121364

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453912300

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454189756

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454189763

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433121371

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1230-0

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (March)

- Keywords

- environment positive change anthropocentrism

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 241 pp., num. ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG