Educational Psychology Reader

The Art and Science of How People Learn - Revised Edition

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- From the Ashes

- Section I: Constructivist and Postformalist Perspectives on Educational Psychology

- 1. Critical Thinking: How Good Questions Affect Classrooms

- THE ROLE OF CRITICAL THINKING IN THE PROMOTION OF SOCIAL JUSTICE

- HOW TO CREATE CRITICAL QUESTIONS

- CONSTRUCTIVIST ACTION LEARNING TEAMS

- THE REAL QUESTIONS

- REFERENCES

- 2. Coming to a Critical Constructivism: Roots and Branches

- JEAN PIAGET: THE DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGIST

- LEV VYGOTSKY AND THE SOCIO-CULTURALTHEORY OF DEVELOPMENT

- CRITICAL PEDAGOGY

- CRITICAL CONSTRUCTIVISM

- REFERENCES

- 3. Critical Educational Psychology

- INTRODUCTION

- EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY

- CONCERNS WITH EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY

- INDIVIDUALISM AND SELFHOOD

- TECHNICAL RATIONALITY

- HISTORICAL, CULTURAL, AND PHILOSOPHICAL CONTEXTS

- CRITICAL EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY

- CRITICAL AS POLYVOCAL

- CRITICAL AS EMANCIPATORY

- CRITICAL AS SOCIOHISTORICAL

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- 4. Beyond Reductionism: Difference, Criticality, and Multilogicality in the Bricolage and Postformalism

- DEFINING BRICOLAGE

- DEFINING POSTFORMALISM

- DIFFERENCE AND MUTUALISM—MULTIPLE PERSPECTIVES AND THE BONUS OF INSIGHT

- USING SUBJUGATED KNOWLEDGES IN THE BRICOLAGE

- A TRANSFORMATIVE POLITICS OF DIFFERENCE

- DIFFERENCE AND COGNITION: BRICOLEURS AS POSTFORMAL THINKERS ABOUT RESEARCH

- MULTILOGICALITY AND CONSCIOUSNESS: POSTFORMALISM AND THE POWER OF MULTIPLE PERSPECTIVES

- POSTFORMALISM, SYNERGIES OF DIFFERENCE, AND NEW MODES OF COGNITION

- BRICOLAGE, DIFFERENCE, AND SELF-AWARENESS IN RESEARCH

- REFERENCES

- Section II: Behaviorism

- 5. Behaviorism and and Its Effect upon Learning in the Schools

- OVERVIEW OF BEHAVIORISM

- CLASSICAL CONDITIONING BY PAVLOV

- CLASSICAL CONDITIONING BY WATSON

- OPERANT CONDITIONING BY SKINNER

- CLASSIFICATIONS OF CONSEQUENCES

- SCHEDULING OF CONSEQUENCES

- GUIDELINES FOR APPLYING CONSEQUENCES

- EFFECTS OF BEHAVIORISM ON EDUCATION

- POSITIVE EFFECT ON EDUCATION AND LEARNING

- NEGATIVE EFFECTS AND LIMITATIONS

- CONCLUSIONS

- REFERENCES

- 6. School Interventions for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Where to From Here?

- THEORETICALLY DRIVEN PSYCHOSOCIAL TREATMENTS FOR ADHD

- SEE NO EVIL

- PATHWAYS AND OUTCOMES

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- 7. A Positive Procedure to Increase Compliance in the General Education Classroom for a Student with Serious Emotional Disorders

- METHOD

- PARTICIPANT

- SETTING

- INTERVENTION

- BEHAVIORAL MEASURES

- EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

- RESULTS

- SECOND OBSERVER RELIABILITY

- VISUAL ANALYSIS OF DATA

- COMPLIANCE

- ACTING OUT

- SUMMARY

- DISCUSSION

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- 8. The Limitations of a Behavioral Approach in Most Educational Settings

- REFERENCES

- Section III: Piaget and Vygotsky

- 9. Dewey’s Dynamic Integration of Vygotsky and Piaget

- INTRODUCTION

- SIMILARITIES BETWEEN DEWEY AND VYGOTSKY

- THE HISTORICAL NATURE OF THE HUMAN BEING

- THE ROLE OF WORK AND THE NOTION OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TOOLS

- THE HEGELIAN DIALECTIC OF BECOMING

- DEWEY AS MEDIATOR BETWEEN VYGOTSKY AND PIAGET

- IMPLICATIONS FOR CONTEMPORARY EDUCATION PRACTICE

- CONCLUSION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

- 10. On the Origins of Constructivism: The Kantian Ancestry of Jean Piaget’s Genetic Epistemology

- PROPERTIES OF THE OBJECT

- KANT’S ”COPERNICAN REVOLUTION”

- TWO TYPES OF KNOWLEDGE: A POSTERIORI AND A PRIORI

- A FINAL THREAD OF THE KANTIAN LEGACY

- RETURNING TO THE QUESTION OF ORIGINS

- REFERENCES

- 11. Jean Piaget and the Origins of Intelligence: A Return to “Life Itself”

- JEAN PIAGET’S BIOLOGICAL VISION OF THE FUNCTIONAL A PRIORI

- ASSIMILATION, ACCOMMODATION AND EQUILIBRATION AND THE PERVASIVENESS OF “CONSTRUCTION”

- “AN ALL-EMBRACING EQUILIBRIUM” AS THE TELOS OF DEVELOPMENT

- THE SUCCESSION OF STAGES OF COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

- SENSORI-MOTOR KNOWLEDGE

- PRE-OPERATIONAL KNOWLEDGE

- CONCRETE OPERATIONAL KNOWLEDGE

- FORMAL OPERATIONAL KNOWLEDGE

- FORMAL LOGIC AND MATHEMATICS AS THE ORIGIN OF INTELLIGENCE

- REFERENCES

- 12. A Cultural-Historical Teacher Starts the School Year: A Novel Perspective on Teaching and Learning

- DEFINITIONS OF EDUCATION: BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE AND PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACHES

- VYGOTSKY AND CULTURAL-HISTORICAL THEORY

- AN ALTERNATIVE VIEW OF THE STUDENT

- THE CURRICULUM AS SOCIOCULTURAL TEXT

- CULTURAL MEANINGS AS SOCIOCULTURAL TEXT

- THE SCHOOL AS A MEANING MAKING SITE

- THE PEREZHIVANIE WITHIN THE ZPD

- TEACHING AND LEARNING AS AN INTEGRATED MEANING-MAKING PROCESS

- REFERENCES

- Section IV: Paulo Freire’s Legacies

- 13. To Study Is a Revolutionary Duty

- REFERENCES

- 14. Eating, Drinking, and Acting: The Magic of Freire

- REFERENCES

- 15. English Language Learners: Understanding Their Needs

- KRASHEN’S SECOND LANGUAGE LEARNING THEORY & STAGES OF SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION

- STAGE THREE: SPEECH EMERGENCE

- CUMMINS’ VIEW OF SECOND LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY

- THE ROLE OF FIRST LANGUAGE LITERACY AND FORMAL SCHOOLING

- SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES RELATED TO LANGUAGE LEARNING

- SOCIAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS

- CULTURAL DIFFERENCES AFFECTING ELL’S ACADEMIC SUCCESS

- FAITH IN THE ELLS

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- 16. Preparing Culturally Responsive Teachers

- WHAT IS CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHING?

- THE ROLE OF EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHER PREPARATION

- ASSIST TEACHERS IN DEVELOPING AFFIRMING ATTITUDES TOWARDS STUDENTS

- SOCIALIZE TEACHERS IN BECOMING CHANGE AGENTS

- UNCOVER TEACHERS’ BELIEFS ABOUT TEACHING AND LEARNING

- INTEGRATE THE SCIENCE OF LEARNING IN CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHER EDUCATION

- ASSIST TEACHERS IN DEVELOPING A FOUNDATION FOR MAKING INFORMED EDUCATIONAL DECISIONS IN THE 21st CENTURY CLASSROOM

- EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGISTS INVOLVED IN CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHER EDUCATION

- CONCLUSION

- NOTE

- REFERENCES

- Section V: Motivation

- 17. Affective and Motivational Factors for Learning and Achievement

- WHAT ROLES DO EMOTIONS (AFFECT) PLAY IN LEARNING?

- WHAT IS EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE?

- WHAT IS MOTIVATION?

- WHAT ARE THE TWO TYPES OF MOTIVATION?

- WHAT ARE THE THEORIES OF MOTIVATION?

- FACTORS THAT AFFECT MOTIVATION

- REFERENCES

- 18. Self-Efficacy: An Essential Motive to Learn

- SELF-EFFICACY AND ITS DIMENSIONS

- SELF-EFFICACY AND RELATED BELIEFS

- ROLE OF SELF-EFFICACY IN ACADEMIC MOTIVATION

- SELF-EFFICACY AND SELF-REGULATION OF LEARNING

- INSTRUCTIONAL AND SOCIAL INFLUENCES ON SELF-EFFICACY BELIEFS

- CONCLUSION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- REFERENCES

- 19. Motivation and Reading: Focus on Content Literacy

- GUIDELINES FOR MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO READ IN THE CONTENT CLASSROOM

- ELEVATING SELF-EFFICACY

- PROVIDING OPPORTUNITIES TO READ BOOKS PERTAINING TO STUDENTS’ INTERESTS

- SELECTION OF CONTENT TEXTBOOKS

- DIGITAL MEDIA

- CONTENT READING STRATEGIES

- PRE-READING STRATEGIES

- K-W-L CHART

- QUICK WRITE

- DURING-READING STRATEGIES

- EXPOSITORY TEXT PYRAMID

- X MARKS THE SPOT

- AFTER-READING STRATEGIES

- THINK-PAIR-SQUARE-SHARE

- REFERENCES

- 20. Encouraging the Discouraged: Students’ Views for Elementary Classrooms

- BACKGROUND

- METHODOLOGY

- RESEARCHING STUDENTS’ PERSPECTIVES

- SITE AND PARTICIPANTS

- DATA COLLECTION

- INTERVIEWS

- DATA ANALYSIS

- PRIZE AS ARTIFACT

- CONSTRUCTIVE CRITICISM THAT ENCOURAGES

- CLOSING REFLECTIONS

- REFERENCES

- 21. Momentous Historical Events as Incentives to Explore History Making

- INTRODUCTION

- A CONSTRUCTIVIST-SOCIOCULTURAL APPROACH OF KNOWLEDGE: RECONSIDERING TEACHING AND LEARNING

- ICT IN EDUCATION

- HISTORY LEARNING AND ITS METHODOLOGICAL FRAME

- HISTORY IN THE DIGITAL ERA

- THE CONSTRUCTION OF HISTORICAL MEMORY IN POSTMODERN REALITY THROUGH POPULAR CULTURE

- POPULAR MEDIA AND THE CONSTRUCTED NATURE OF CULTURAL MEMORY

- TYPOLOGIES OF MATERIAL

- METHODOLOGY AND GOALS OF THE PROJECT

- PROCESS

- STAGE 1

- STAGE 2

- STAGE 3: COMICS

- FINAL STAGE

- TWHISTORY

- COUNTERFACTUAL HISTORY

- SAMPLE OF A REENACTMENT

- SAMPLE OF A COUNTERFACTUAL NARRATIVE

- EVALUATION STAGE

- CONCLUSIONS

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

- Section VI: Complex Ecologies for Educational Psychology

- 22. The Centrality of Culture to the Scientific Study of Learning and Development: How an Ecological Framework in Educational Research Facilitates Civic Responsibility

- WARRANTS FROM NATURAL SCIENCE AND THE FIELD OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

- ADAPTABILITY AS A CHARACTERISTIC OF THE HUMAN SPECIES

- WARRANTS FROM THE FIELD OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

- SUMMARY OF WARRANTS

- CONCEPTUAL IMPLICATIONS OF A CULTURAL LENS: TOWARD AN INTEGRATED THEORY OF LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT

- RESEARCH EXAMPLES OF THEORY DERIVED FROM EXAMINATIONS OF PRACTICE IN COMMUNITIES OF COLOR

- LEARNING IN EVERYDAY SETTINGS IN THE RESEARCH OF NAILAH NASIR

- STUDIES OF ECOLOGICAL REASONING IN INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES: MEDIN AND BANG

- CULTURAL MODELING

- IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY AND PRACTICE

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

- 23. Dealing with Cultural Collision in Urban Schools: What Pre-Service Educators Should Know

- NOTIONS OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICA AND SCHOOLS

- THE URBAN CONTEXT AND POPULAR CULTURE

- HIP-HOP CULTURE

- TELEVISION MEDIA

- IDENTITY THEORY AND BLACK YOUTH

- SCHOOL CULTURE

- INTERSECTION OF SCHOOL CULTURE AND BLACK POPULAR CULTURE

- IMPLICATIONS FOR EDUCATORS

- REFERENCES

- 24. Creating a Classroom Community Culture for Learning

- TRADITIONAL MODELS

- EFFECTIVE LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS

- BUILDING A CLASSROOM CULTURE

- DREIKURS’ LOGICAL CONSEQUENCES

- CRITICAL CONSTRUCTIVIST MODEL: A CULTURE OF MUTUAL ENHANCEMENT

- RULES TO LIVE BY. . .

- REDUCING HATE CRIMES AND VIOLENCE IN THE SCHOOL AND COMMUNITY

- REFERENCES

- Section VII: Enlivened Spaces for Enhanced Learning

- 25. Researching Children’s Place and Space

- THE SIGNIFICANCE OF CHILDREN’S PLACE AND SPACE

- EXAMPLES OF PARTICIPATORY PLACE RESEARCH WITH CHILDREN AND YOUTH

- UNESCO GROWING UP IN CITIES PROJECT

- INITIATIVES TO IMPROVE SCHOOL GROUNDS

- PROJECT FOR PUBLIC SPACES AND TEENS TURNING PLACES AROUND

- CHILDREN AND PLACE RESEARCH IN EDUCATION

- NARRATIVE OR ETHNOGRAPHIC CASE STUDY RESEARCH

- FAVORITE PLACE ANALYSES

- CLOSING DISCUSSION

- REFERENCES

- WEBSITES

- 26. Infinite Jurisdiction: Managing Achievement In and Out of School

- INDIVIDUAL/SYSTEM

- NARRATIVES OF STUDENTS AND FAMILIES

- BLAME

- INFINITE JURISDICTION/CONTROL

- REMAINING IN/LEAVING THE URBAN CLASSROOM

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- 27. Envisioning the Environment as the Third Teacher: Moving Theory into Practice

- WRITING “PLACE STORIES” (JULIA)

- WEDGED BETWEEN A SHIMMERING ROCK AND A HARD PLACE (TERESA)

- “POMEGRANATES IN TSFAT” (SHERYL)

- THE “ENVIRONMENT” AS THIRD TEACHER

- CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- NOTE

- REFERENCES

- Section VIII: Parents and Other Relationships

- 28. Teacher and Family Relationships

- CHILDREN AND FAMILIES

- REFLECTIVE PRACTICE—BEING A THOUGHTFUL, PENSIVE PRACTITIONER

- TEACHERS AS PARENTS

- TEACHERS ARE NOT PARENTING EXPERTS

- PARENTING IS NOT A PROFESSION

- CHILDREN ARE PRECIOUS TO PARENTS

- NEGOTIATING THE RELATIONSHIP: TEACHER AND PARENT COOPERATION

- WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO BECOME A PARENT?

- CREATING A SAFE EMOTIONAL ENVIRONMENT

- INVOLVING FAMILIES AND FACILITATING COOPERATION

- THE BEGINNING OR NOVICE TEACHER

- REFERENCES

- 29. Personal and Social Relations in Education

- PERSONAL RELATIONS

- SOCIAL RELATIONS

- CONCLUSION

- NOTES

- 30. Relations Are Difficult

- DOMESTICATING EDUCATION

- STUNNING IGNORANCE

- UNCANNY RESEMBLANCE

- MISTAKING CLICHÉ FOR STUDENT VOICE

- FAMILY AS THE CAUSE OF RACISM, AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS THE CURE

- MOVING OUT OF THE SELF, OUT OF IDENTITY, AND INTO A VERTIGO OF ACTION

- HATE CRIMES, FAMILIES, AND CARING

- NOTES

- Section IX: Educational Psychology Inside and Outside the Classroom

- 31. Using the Lesson Study Approach to Plan for Student Learning

- WHAT IS LESSON STUDY?

- THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

- RESEARCH ABOUT PLANNING

- USING LESSON STUDY WITH MIDDLE SCHOOL TEACHERS

- LESSON STUDY IN ACTION

- MENTORING TEACHER CANDIDATES

- ADVICE FOR TEACHERS AND ADMINISTRATORS

- CONCLUSIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- REFERENCES

- RECOMMENDED SOURCES

- 32. Sailing and the Experience of Learning

- EDUCATIVE EXPERIENCES

- ACTIVITIES CONSISTENT WITH DEWEY’S CONCEPTION OF EXPERIENCE

- FEATURES OF DEWEYIAN LEARNING ACTIVITIES AND ENVIRONMENTS

- THE DEWEYIAN EDUCATIVE EXPERIENCE IN THE CLASSROOM

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- 33. Open Lessons: A Practice to Develop a Learning Community for Teachers

- THE CHALLENGE IN OVERCOMING THE ISOLATED CULTURE OF TEACHING

- A PRACTICE TO DEVELOP A LEARNING COMMUNITY FOR TEACHERS

- ABCS OF THE OPEN LESSON

- A CASE OF AN OPEN LESSON

- IMPLICATIONS OF OPEN LESSONS

- CODA: FUNCTIONS OF OPEN LESSONS

- REFERENCES

- 34. Using Visualization and Deep Breathing

- MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT VISUALIZATION

- DISTRESS AND HIGH-ABILITY STUDENTS

- LEARNING AND USING VISUALIZATION AND BREATHING TECHNIQUES

- SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

- REFERENCES

- 35. Social and Personal Development

- FREUD FOR EDUCATORS

- COPING WITH EGO

- DEFENSE MECHANISMS

- COMPLEX

- SCHOOL LIFE AND EGO

- PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT AND IDENTITY

- SOCIAL IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT

- EGO AND EURO-DUALISTIC EPISTEMOLOGY

- YIN AND YANG

- MOVING OUT OF THE EGO CIRCLE

- HUMANISTIC APPROACH

- KIZUNA

- TRUST, RESPONSIBILITY AND RESPECT

- REFERENCES

- Section X: Discursive Practice in Educational Psychology: How the Subject Tells the Truth about Itself

- 36. Disciplining the Discipline

- DISCIPLINE: CONTROL OF BODIES

- THE FORMATION OF DISCIPLINARY PRACTICES

- DISCIPLINARY TECHNOLOGIES

- HIERARCHICAL OBSERVATION

- NORMALIZING JUDGMENT

- THE “EXAMINATION”

- DISCIPLINARY TECHNOLOGIES IN EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY

- SURVEILLANCE PRACTICES

- CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

- TESTING AND THE PRODUCTION OF STUDENTS

- REFERENCES

- 37. An Introductory Argot of Gifted Education

- THE ELUSIVE DEFINITION—IS THIS LEARNER GIFTED?

- WHO AND WHAT HAS INFLUENCED GIFTED EDUCATION?

- WHAT ARE SOME CRITICAL IDENTIFICATION AND ASSESSMENT ISSUES?

- WHY ARE THE GIFTED UNIQUE?

- WHAT ARE SOME APPROPRIATE MODELS FOR GIFTED LEARNERS?

- WHAT ARE APPROPRIATE PROGRAM OPTIONS FOR GIFTED LEARNERS?

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- 38. Self-regulated Learning

- INTRODUCTION

- HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

- CONCEPTUAL DISTINCTIONS

- REGULATORY LEARNING THEORY

- CONCEPTUAL COMPATIBILITY: INTEGRATION AND INTERACTION

- SRL PEDAGOGY: CONTENT, FORMATS, AND ENVIRONMENTS

- PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO LEARN

- PEDAGOGICAL FORMATS: HOW TO TEACH SRL

- INSTRUCTIONAL ENVIRONMENTS

- CRITICAL CONCERNS

- SELF AND PERSONHOOD: WHAT SELF UNDERPINS SRL?

- INDIVIDUAL AND SOCIAL BETTERMENT: WHO BENEFITS FROM SRL?

- EMPOWERMENT AND AGENCY: IS SRL AN EXPRESSION OF PERSONAL CONTROL?

- THE ENDS OF SRL: LEARNING CONTEXTS AND OBJECTIVES

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- 39. Inquiry-based Learning with International Students: An Exploration in Pedagogic Values

- INTRODUCTION

- NEEDS OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS

- WHAT DO WEMEAN BY INQUIRY-BASED LEARNING?

- THE STUDY

- INFORMATION LITERACY

- DISCUSSION

- DIFFERENCE

- RESPONSIBILITY

- CONCLUSION

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

- REFERENCES

- Section XI: Alternative Education, Urban Youth, and Interventions

- 40. Therapeutic Art, Poetry, and Personal Essay: Old and New Prescriptions

- THEORY

- LITERATURE OF LEARNING AND WOUNDED STUDENTS

- METHODOLOGY

- RESULTS

- BEGINNING SUBLIMATION

- ADVANCED SUBLIMATION

- ON FAMILIES, FRIENDS, AND THEMSELVES

- DISCUSSION OF LEARNING

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- 41. Alternative School Adaptations of Experiential Education

- BRIDGING MULTIPLE WORLDS

- ADD COMPASSION

- MORE ON EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING FOR STUDENTS AND TEACHERS

- MODULATING THE EMOTIONAL TONE

- SPECIAL METHODOLOGIES FOR ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION

- REFERENCES

- 42. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Life Space Crisis Intervention (L.S.C.I.)

- INTRODUCTION

- BRIEF OVERVIEW OF LSCI

- RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- METHOD

- SAMPLE

- PROCEDURES

- OUTCOME EVALUATION

- MEASUREMENT

- CAUSAL ATTRIBUTIONS

- REACTIONS TO MISBEHAVIOR

- SELF-EFFICACY

- DESIGN AND ANALYSIS

- RESULTS

- LSCI PROCESS EVALUATION

- OUTCOME EVALUATION

- ANOVA ANALYSES

- REACTIONS TO MISBEHAVIOR

- SELF-EFFICACY

- FOCUS GROUP RESPONSES

- BELIEFS THAT WERE CHALLENGED

- IMPACT ON STUDENTS

- DISCUSSION

- LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS

- CONCLUSIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- REFERENCES

- 43. Doing Restorative Practices Justice: Questioning the Psychology of Affect Theory

- INTRODUCTION

- RESTORATIVE PRACTICES

- AFFECT THEORY

- CONSTRUCTING SHAME AND PRACTICING SHAMING

- PRACTICAL RESPONSIBILITIES

- CONCLUSIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

- REFERENCES

- 44. Urban Dropouts: Why Persist?

- WHY DO URBAN STUDENTS FAIL TO PERSIST IN SCHOOL?

- URBAN DROPOUTS: PEOPLE MAKE THE DIFFERENCE

- CONCLUSIONS

- REFERENCES

- Section XII: Matters of Assessment

- 45. Test Anxiety: Contemporary Theories and Implications for Learning

- TYPES OF TEST ANXIETY

- STATEVS. TRAIT ANXIETY

- EMOTIONALITY VS. WORRY

- ZEIDNER’S TYPOLOGY FOR TEST-ANXIOUS LEARNERS

- TEST ANXIETY AND THE LEARNING-TESTING CYCLE

- TEST PREPARATION PHASE

- TEST PERFORMANCE PHASE

- TEST REFLECTION PHASE

- MANAGING TEST ANXIETY

- REFERENCES

- 46. Paying Attention and Assessing Achievement: Assessment and Evaluation: Positive Applications for the Classroom

- HISTORY

- STANDARDIZED GROUP TESTS

- APPROPRIATE ASSESSMENT

- TEACHER-MADE ASSESSMENTS

- CLASSROOM ASSESSMENT

- CONSULTATION WITH OTHER TEACHERS AND PARENTS

- CLASSROOM OBSERVATIONS

- METHODS FOR OBSERVING AND RECORDING BEHAVIOR

- REAL-TIME OBSERVATIONS

- ANTECEDENT-BEHAVIOR-CONSEQUENCE ANALYSIS

- FREQUENCY OR EVENT RECORDING

- OTHER METHODS

- OBSERVING MORE THAN ONE CHILD

- SELF-OBSERVATION

- CURRICULUM-BASED ASSESSMENT

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- 47. The Common Core State Standards

- FRAMEWORK FOR CURRICULUM

- THE CURRENT STANDARDS MOVEMENT

- THE COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS INITIATIVE: ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS AND LITERACY AND MATHEMATICS

- ADDRESSING THE LEVEL OF RIGOR IN THE COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS: CURRICULUM

- ADDRESSING THE LEVEL OF RIGOR IN THE COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS: INSTRUCTION

- ADDRESSING THE LEVEL OF RIGOR IN THE COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS: ASSESSMENT

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- Section XIII: Teaching Educational Psychology and Teaching Teachers

- 48. Learning to Feel Like a Teacher

- PERSONAL IDENTITY FROM WITHIN AND WITHOUT

- RECONCILING STABILITY AND FLUX: THE FUTURE TEACHER’S DILEMMA

- SORTING THROUGH THE CONFUSION OF DISCOURSES

- THE POSSIBILITIES AND LIMITS OF BEING TRULY HELPFUL

- ASSIGNMENTS MEANT TO FOSTER PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT

- ADMINISTRATIVE ARRANGEMENTS MEANT TO FACILITATE IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT

- ASSISTING IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT IN SPITE OF IT ALL

- REFERENCES

- 49. Once Upon a Theory: Using Picture Books to Help Students Understand Educational Psychology

- MOTIVATIONAL ASPECTS OF CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

- THE COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF PICTURE BOOKS: STORIES AND ILLUSTRATIONS

- STORIES AND NATURAL COGNITION

- ILLUSTRATIONS: A PICTURE IS WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS

- PICTURE BOOK SELECTION AND USE

- CONCLUSION

- CHILDREN’S BOOKS CITED

- REFERENCES

- 50. Toward a Psychology of Communication: Effects of Culture and Media in the Classroom

- WHAT IS COMMUNICATION?

- VERBAL AND NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION

- CULTURAL COMMUNICATION INFLUENCES

- ATTITUDES, BELIEFS AND VALUES

- IMPERSONAL AND PERSONAL INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION

- MEDIA INFLUENCES IN THE CLASSROOM

- FIRST CLASS MEETING PREPARATION

- HANDLING THE UNEXPECTED

- NOTE

- REFERENCES

- Contributors

| xi →

I would like to express my profound gratitude to all of the Reader’s co-authors for their contributions to this book’s distinction. Their scholarship and dedication to the improvement of learning reflect a true appreciation of the values of both educational psychology and critical pedagogy within the multiple processes and contexts of learning. Special thanks to new contributors Tim Corcoran, James Sparks, Kamau Siwatu, Tehia Starker, Steven Wojcikiewicz, Zachary Mural, David Monetti, James Reffel, Jennifer Breneiser, David Tack, Evangelia Moula, and Marilyn Howe.

A work of this size and magnitude requires the effort of many individuals. As the days turned to months, and the months turned to years, the staff at Peter Lang are foremost on my indebtedness list. Bernadette Shade, Sophie Appel, Patty Mulrane, Phyllis Korper, and Chris Myers all deserve my heartfelt appreciation for their sedulous efforts, patience, and perseverance in seeing this project through to completion.

Great gratitude is extended to the following permission editors and their respective publication’s boards for releasing copyrights and reprint permissions for these chapters and articles:

Peter Lang Publishing for permission to reprint from:

Educational Psychology: An Application of Critical Constructivism (2008), Greg S. Goodman, Ed.

Chapter 1. Critical Thinking: How Good Questions Affect Classrooms by Greg S. Goodman.

Chapter 2. Coming to a Critical Constructivism by Greg S. Goodman.

Chapter 14. English Language Learners: Understanding Their Needs by Binbin Jiang.

Chapter 16. Affective and Motivational Factors for Learning and Achievement by Patricia Kolencik.

Chapter 24. Cultural Collision in Urban Schools: What Pre-service Teachers Should Know by Floyd Beachum and Carlos McCray.

Chapter 26. Creating a Classroom Community Culture for Learning by Suzanne Gallagher and Greg S. Goodman.

Chapter 30. Teacher and Family Relationships by Tamar Jacobson. ← xi | xii →

Chapter 44. Assessment by Karen T. Carey.

Chapter 49. Toward Psychology of Communication: Effects of Culture and Media in the Classroom by Joanne Washington.

Educational Psychology: Disrupting the Dominant Discourse by Suzanne Gallagher (2003):

Chapter 37. Disciplining the Discipline by Suzanne Gallagher.

No Education Without Relation, C. Bingham and A.M. Sidorkin, Eds. (2004)

Chapter 31. Personal and Social Relations in Education by Barbara J. Thayer-Bacon.

Chapter 32. Relations Are Difficult by Cris Mayo.

Jean Piaget: Primer by D. Jardine (2006)

Chapter 9. On the Origins of Constructivism: The Kantian Ancestry of Jean Piaget’s Genetic Epistemology by D. Jardine.

Chapter 10. Jean Piaget and the Origins of Intelligence: A Return to “Life Itself” by D. Jardine.

19 Urban Questions by S. Steinberg, Ed. Second edition (2010)

Chapter 42. Urban Dropouts: Why Persist by G.S. Goodman & A.A. Hilton.

Self-Regulated Learning by Stephen Vassallo (2013)

Chapter 3. Critical Educational Psychology.

Chapter 34. Self-regulated Learning.

Teach for America by Katherine Crawford-Garrett

Chapter 44. Infinite Jurisdiction.

Mirrors of the Mind by Noriyuki Inoue (2012)

Chapter 50. Social and Personal development.

Paradigm Publishers for permission to reprint from Sonia Nieto’s Dear Paulo: Letters from Those Who Dare Teach (Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers 2008).

Chapter 12. To Study Is a Revolutionary Duty by Jeff Duncan-Andrade (pp. 154–163).

Chapter 13. Eating, Talking, and Acting: The Magic of Freire by Herb Kohl (pp. 115—119).

Thank you to Charlie Finn for permission to quote these lines from “Please Hear.” The full poem can be found at http://www.poetrybycharlescfinn.com

Chapter 4. I also wish to thank Shirley Steinberg for the permission to print Joe Kincheloe’s Beyond Reductionism: Difference, Criticality, and Multilogicality in the Bricolage of Postformalism. This work appears in Educational Psychology Reader for the first time.

Chapter 5. Reprinted by permission of the publisher: www.nasponline.org. Barkley, R. (2007). School interventions for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Where to from Here? In School Psychology Review, Vol. 36 (2), 279–286. Copyright 2007 by the National Association of School Psychologists, Bethesda, MD.

Chapter 8. Reprinted by permission of the publisher: Purdue University Press (2008) Bryan Shaffer, Editor: Mayer, S.J. (2008). Dewey’s Dynamic Integration of Vygotsky and Piaget by Susan J. Mayer. The Journal of the John Dewey Society of Education and Culture 24 (2), 6–24.

Chapter 17. Reprinted by permission of the publisher Rightslink: Zimmerman, B. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 82–91. ← xii | xiii →

Chapter 20. Reprinted by permission of publisher Mort Morehouse: Analytic Teaching: Encouraging the Discouraged by Julia Ellis, Susan Fitzsimmons, and Jan Small-McGinley

Chapter 22. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Rightslink: Lee, C. (2008). The centrality of culture to the scientific study of learning and development: How an ecological framework in educational research facilitates civic responsibility. Educational Researcher, 37(5), 267–279.

Chapter 27. Reprinted by permission of publisher Alan Jones: www.csse.ca/cacs/jcacs Ellis, J. (2004). Researching Children’s Place and Space. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 20(1), 83–100.

Chapter 33 . Reprinted with permission from the publisher: National Middle School Association. Lenski, S. J. &Caskey, M. M. (2008). Using the lesson study approach to plan for student learning. Middle School Journal, 40(3), 50–57.

Chapter 34. Reprinted by permission of the authors: Shen, J., Zheng, J., & Poppink, S. (2007). Open lessons: A practice to develop a learning community for teachers. Educational Horizons, 85(3), 181–191.

Chapter 40. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Hampton Press: J. Jelmberg & G. S. Goodman (2008). The Outdoor Classroom: Integrating Learning and Adventure. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Chapter 46. Reprinted by permission of the Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, Issue #32, July 1, 2004. © by CJEAP and the author(s): Seifert, K. (2004). Learning to feel like a teacher: Personal identity from within and without. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 32.

Chapter 47. Reprinted by permission of the publisher: Teaching Educational Psychology (2005). Zambo, D., & Hansen, C. (2005). Once upon a theory: Using picture books to help students understand educational psychology. Teaching Educational Psychology, 1(1), 1–8.

*

Most importantly, a loving thank-you to my #1 supporter, Andy, for her patience with my time away on this project.

| xiv →

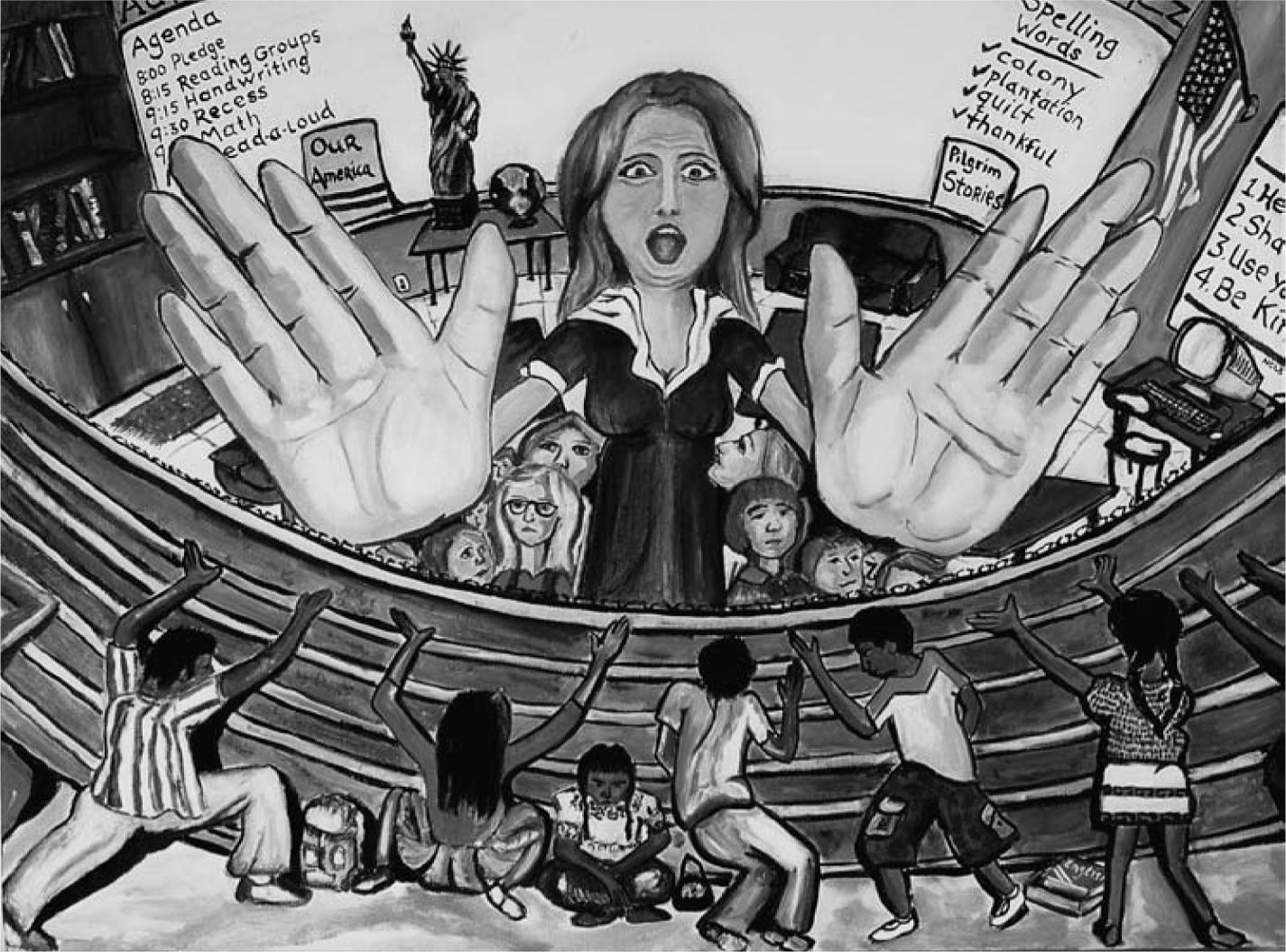

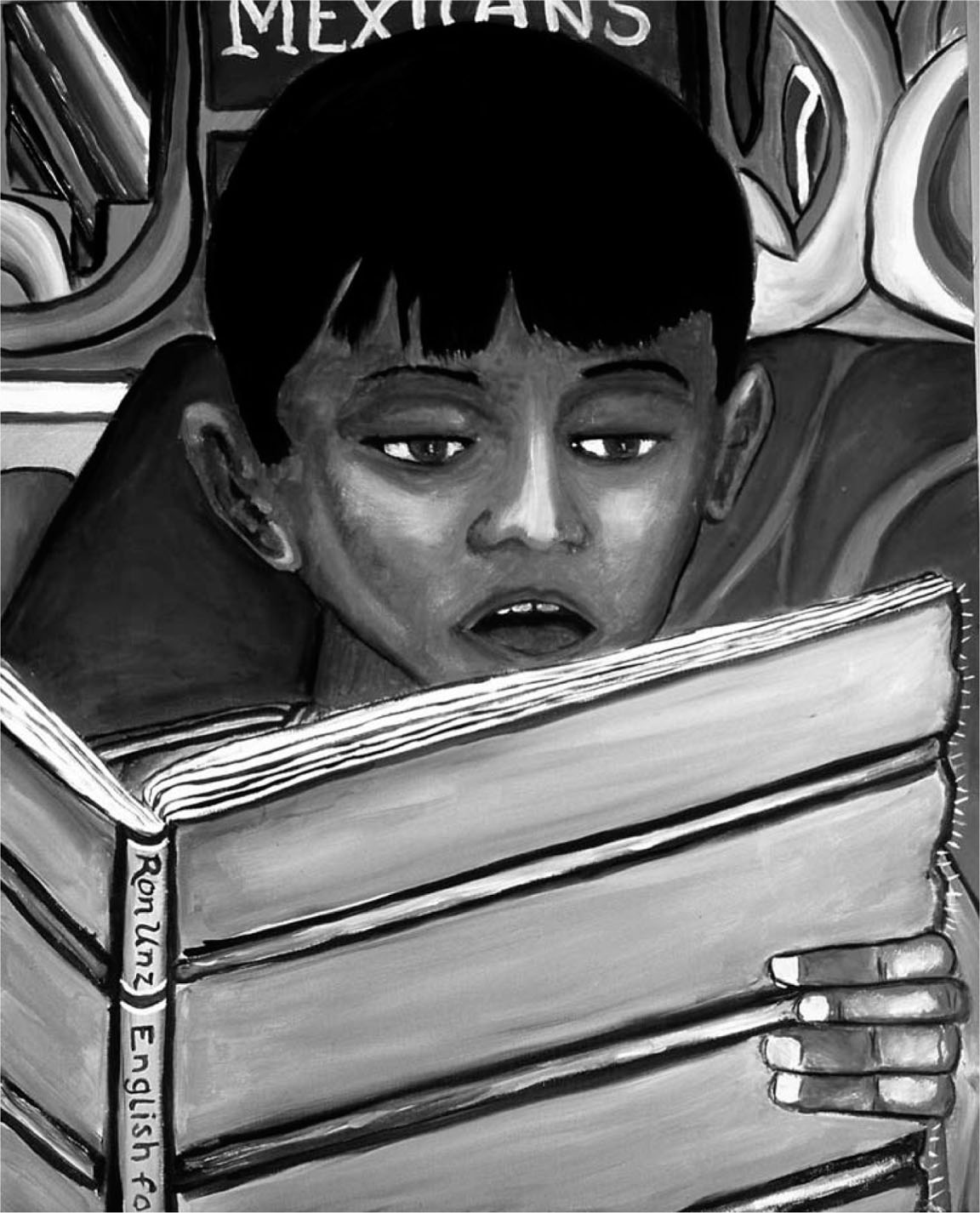

Artwork by Christian J. Faltis

| xv →

This book takes educational psychology out of the hands of scholarship that examines how people learn as individuals and places it squarely in the palms of lived realities of today’s children and adolescents, arguing that learning is social as well as cognitive, and that learning has social consequences. All of the authors in this book ask readers to consider that what students learn is as important as how they learn it. To this end, the book seeks to engage readers in a dialogue about social justice and the need to engage in school experiences where students pose critical questions about the curriculum, expose its vested interests and hidden agendas, and ultimately, become agents of change.

Much of the early work in educational psychology viewed learning as something that happens entirely inside the head of learners, which eschews the role of social interaction learners have with the environment and thus avoids dealing with critical issues that impact students. From its beginning, educational psychology focused its attention on social, moral, and cognitive development, with an eye toward the creation of theoretical ideas that could be applied to educational settings, such as schools and classrooms. Teacher education programs, in particular, have relied on the seminal work of Piaget, Bandura, and Bloom, among others, to help students become acquainted with theoretical principles that underlie the strategies, lessons, and classroom management processes they will be expected to learn and use in teaching. While many of the principles created by these educational psychologists continue to inform teacher education programs, this book argues for a stance toward teaching and learning that goes well beyond individual learning, to one that necessarily ties teaching and learning to issues of social justice for children and adolescents who have been historically and are presently underserved and marginalized by school practices and policies.

It is important to consider that early theoretical ideas about teaching and learning were developed either in laboratories or in countries outside the U.S. long ago. Moreover, since social factors and social contexts were considered extraneous for understanding how learning occurs, the theoretical principles resulting from this early work were thought to apply to any and all contexts where students ← xv | xvi → were in a position to learn. After all, if the conditions were right, so it was thought, students would acquire the knowledge inside their heads just as the teacher presented it, following the principles of learning dictated by theory that was discovered in laboratories and other places where conditions were controlled and learning was observed.

This book asks readers to reconsider educational psychology and to place it in real settings, where children and adolescents bring to classroom a wide range of experiences and background knowledge that earlier theoretical pioneers of learning theory could not have imagined. Remember that when Bloom, Bandura, Piaget, and Skinner (and to some extent, Vygotsky) created their theoretical work, they worked with students from dominant groups. Their work was developed at a time in the U.S. when schools for minority students were drastically unequal, when the lives and experiences of non-White students and other marginalized students were absent from the curriculum. Few of their followers questioned the generalizability of their work to situations where learners of diverse language, gender, social class, and ethnic backgrounds were together in classrooms. None of these early educational psychologists questioned whether their work legitimized the interests of the dominant groups and at the same time suppressed the knowledge and experiences of minority and marginalized groups. The authors in this book do, and they offer ways to counter social injustices that have accumulated from decades of neglect resulting from a concern for individual learning that ignores the social realities of poverty, racism, intolerance, and social stratification.

In today’s classrooms, many students are immigrants and children of immigrants who live in poverty and are likely to enter school speaking a language other than English. Many schools in urban settings are likely to be hypersegregated, attended mainly by students of one ethnicity who are bilingual or becoming bilingual. There is a growing trend of schools where the overwhelming majority of students are African American, or Mexican and Mexican American, or Puerto Rican and African American, with few White students as classmates. Likewise, much like in the days of legalized segregation, there are schools where almost all of the students are White and have little or no contact with students of other ethnicities or language groups. As the authors of this book point out, in today’s schools, it takes much more than understanding learning theory to address the learning needs of diverse school populations. It takes a critical stance for social justice, where students are led to question what is legitimate knowledge in light of the lived experiences of marginalized and oppressed groups.

This brings us to the central thesis of this book: The need for critical consciousness and change to be firmly embedded in our work in schools. The authors in this book point out the limitations of educational psychology concerned with how children develop socially and cognitively through constructivism, which highlights the role of learners in actively constructing and appropriating what for them are new ideas. The main area of concern is not entirely with the theoretical principles associated with constructivism but rather the absence in the early work of any reference to what students learn, especially as it relates to social justice issues and critical consciousness of social stratification based on language, ethnicity, social class, gender and race. Constructivism implies that students are active learners in creating meaning through scaffolded interaction with others. Critical constructivism, using Vygotskian social learning principles and following Paulo Freire’s approach to critical pedagogy, goes well beyond the creation and appropriation of new meaning; it asks students to question whose meanings count and who benefits from meanings that exclude, that place the values of the dominant group over others, and that perpetuate myths about the poor and oppressed peoples of the world. These are serious questions that need to be posed and addressed in today’s schools as teachers are strapped with standards, testing, and accountability. On top of all these encumbrances, bilingual education ← xvi | xvii → is increasingly outlawed as an educational approach. These dictates are a thinly veiled attempt by the dominant group to maintain its power by implementing educational policies that in fact are a means to ensure that the voices and needs of immigrant children, poor children, English language learners, and other stigmatized groups are not heard. This book challenges readers to engage in dialogue with students about the world around them, to pay attention to social injustice, and to put forth solutions to the problems they pose. Among the many themes and topics that inquire about social justice are the following:

| Advocacy | N-word |

| Bilingual Education | Oppression |

| Critical Race Theory | Poverty |

| Discrimination | Queer Theory |

| English-Only | Racism |

| Feminism | Spanglish |

| Genocide | Tracking |

| Homophobia | Undocumented |

| Immigration | Varieties of Language |

| Jingoism | White Privilege |

| Ku Klux Klan | Xenophobia |

| Linguicism | Youth Movements |

| Minutemen | Zealots |

Each of these social justice topics is open-ended and requires much scaffolded discussion and dialogue, reading and writing, as well as inquiry and action to critically construct deep understanding of their meanings and implications for a better world for marginalized and oppressed groups. The hope of creating a more socially just world by understanding how students learn coupled with what they learn rests squarely on the shoulders of teachers and students who engage in topics that challenge systems of domination. This book provides students of educational psychology with new hope and a set of tools for reaching that goal.

| xviii →

Artwork by Christian J. Faltis

| xix →

From the Ashes

All the night the old school burned

probably arson, no culprit.

And all the children were happy.

Search the ashes

all gone, desks, books, and blackboards, all gone.

And all the children were happy.

Community, school board and administrators met

to plan rebuilding at once

And all the children were sad.

Board chair had been elected despite his philosophical nature.

He appointed a planning committee

of children and his very best teachers.

And all the children were glad.

Teachers asked children what they wanted.

A playground, of course,

so the teachers designed a playground

that would provide healthy exercise.

And all the children were glad they were getting their way. ← xix | xx →

Children had to have pets.

Chickens for eggs and rabbits for fun.

Birdhouses and feeders and a couple of cats.

And all the kids were happy.

What else should we do?

The children wanted to be outside

so the teachers planned a big garden plot.

And all the children were excited.

So what else?

Lights for the playground so we can play late

and what is good to plan for the solar system.

And all the children were curious.

Many computers and games.

New game shoot words at Silent Sam

to help him communicate.

And all the children laughed

The building plans were then complete

and now the tools to make it work.

And all the children listened carefully.

Seed catalogues, calculators to check produce sales

and profits and expenses for the chickens,

weather information for the weather station,

nutrition books to go with garden and gym.

Software to look up plants and their history,

math books to figure percent of nice days and poetry

to read to the chickens and plants. All this and much more.

And all the children were happy and ready to go back to school.

Out of the ashes came a new school where the children helped

design the building and for what it was used.

And all the children were happy.

| 1 →

Constructivist and Postformalist Perspectives on Educational Psychology

| 3 →

How Good Questions Affect Classrooms

This chapter presents the notion that critical thinking is one of the keys to your success as a person: be that as a citizen or as a teacher. Developing ways to use your mind to explore concepts, theories, events, or assumptions is a good place to start. To begin this discussion, let us ask ourselves some questions: How is critical thinking different than thinking in general? Is it always necessary to think critically? What values or benefits exist in asking critical questions? How do we begin to create critically meaningful questions?

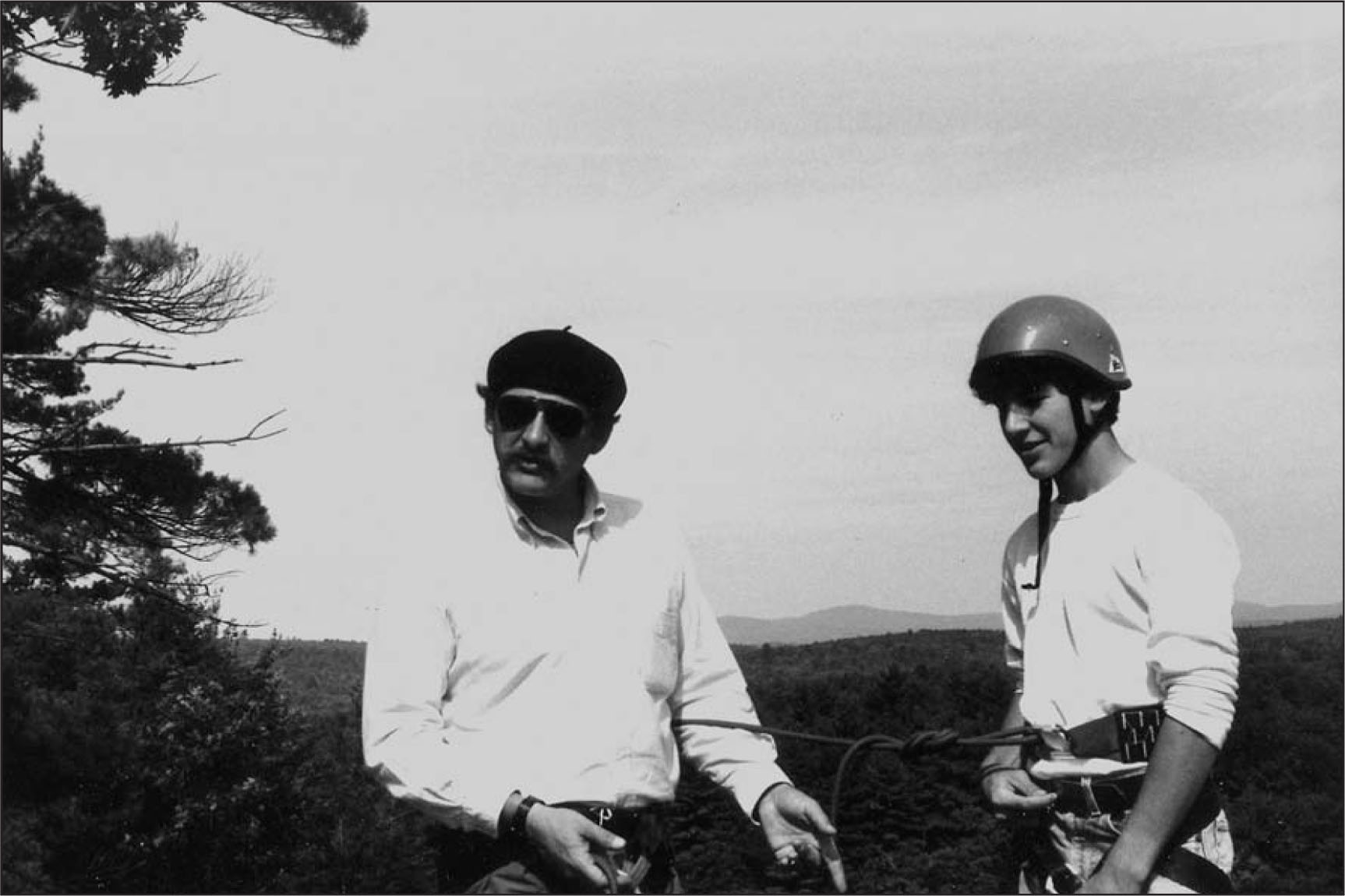

Many professors of education consider John Dewey to be one of the foremost philosophers in Americans history. Philosophers are valued for their critical thinking and intellectual contributions to society. As an educational philosopher, Dewey gave us many ideas to ponder. One of the best of Dewey’s contributions was the notion that learning is the process of thinking about experience. In Dewey’s (1944) words, “No experience having meaning is possible without some element of thought” (p. 143). This contribution is immediately simple to understand, yet it is profound in its implications for us as teachers, and it is worthy of a deeper investigation. To assist in displaying how Dewey’s words affected me as a teacher, I will share this example from my favorite teaching lesson: rappelling.

As a young college student, fresh out of 13 very boring years of public and private schooling, I was eager to learn of exciting and new ways to use my mind. Encouraged by my mentor Peter Ordway to attend a school called Outward Bound, I discovered how to rappel (how to descend mountains using a rope). Having had this experience of scaring myself half to death and realizing that I could do very bold things and not be limited in my experience by fear, the thing that I wanted to do most was to share this natural high with others. To teach outdoor education became my goal, and teaching rappelling would become my best lesson. ← 3 | 4 →

The days of climbing and rappelling always held excitement, and they were never boring. This is not to say that teaching on the edge of the cliff was sufficient for me as a teacher. I took inspiration from some instruction by Jed Williamson, president of Sterling College. Jed once shared with me that my rappelling lesson had a high “C.T.” factor. When I asked what “C.T.” meant, Jed smiled and said, “Cheap Thrills.” For those unable to get beyond the immediate experience of rappelling, this is true. Jed inspired me to seek something more from the experience. My challenge as a teacher was to help my students see this experience as a metaphor for other challenges in their lives. Rappelling was my best teaching aid for overcoming fear and personal obstacles. The real learning for climbers is not the obvious technique business of knots, slings, and belays, but it is in the internal examination of one’s fear, courage, ingenuity, integrity, and identity.

I would instruct my students that for some of them, the courage to attend this class on the cliff required more character than it does for the ones who blithely hop down the rock face, high on adrenaline. In my introductory safety, outdoor “bathroom” rules, etcetera lecture, I would allude to Dewey’s words, learning is the process of thinking about experience, to communicate the message that this day and lesson were not about learning to rappel. Today’s lesson was about reflecting upon your own courage and ability to overcome personal limitations. To give this meaning to sixth graders, I would add, “There are no chickens on the rock today. For several of you, it took more courage to get up and get on the bus to come out here than it will take for others to descend this cliff.”

Rappelling can be a pathway to personal discovery; however, the real learning comes from reflecting on the experience and using that knowledge for your life’s benefit. Learning that you can overcome obstacles and that you do have the courage that you will need to endure: these are the big lessons. Teaching something as important as this was the reason I so enjoyed my lesson on rappelling. ← 4 | 5 → I was really trying to teach students to think critically about themselves. What does it mean to have courage? What is a moral equivalent for your bravery today? In what ways did you confront your own perceptions of self by doing this rappel? How did today’s experience change the way you see someone else in your class?

As a climbing teacher, it is relatively easy to make learning exciting. It is all in the rock. What about math, English, or social studies teachers? How will you make your subject have personal meaning for your students? Some would argue that the subject matter is not relevant. What is important is teaching learning processes: logical thinking, creative and divergent thinking, critical thinking, and using the mind’s multiple capacities or intelligences (Gardner, 1983). For all teachers, assisting in the development of the knowledge, dispositions, and skills of critical thinking may be the most valuable of the contributions they can imbue upon their students regardless of the specific subject matter at hand. In fact, educators may argue that some of the most important work ahead in this century is in engaging students through meaningful and relevant discourse to consider their potential role and become critical citizens (Giroux, 1998). Critical citizens are individuals who take seriously their ethical, moral, and philosophic responsibilities to create communities that care about the environment, the culture, and the people they include.

More than ever, the sheer magnitude of human knowledge renders its coverage by education an impossibility; rather, the goal of education is better conceived as helping students develop the intellectual tools and learning strategies needed to acquire the knowledge that allows people to think productively about history, science and technology, social phenomena, mathematics, and the arts. Fundamental understanding about subjects, including how to frame and ask meaningful questions about various subject areas, contributes to individuals’ more basic understanding of principles of learning that can assist them in becoming self-sustaining, lifelong learners. (From “How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School” (p. 5) http://new ton.nap.edu/html/ howpeople1/ch1.html)

The Bellevue Community College “Critical Thinking and Information Literacy Across the Curriculum” faculty have developed a solid rubric for defining critical thinking. Critical Thinking recognizes:

• Patterns and provides a way to use those patterns to solve a problem or answer a question

• Errors in logic, reasoning, or the thought process

• What is relevant or extraneous information

• Preconceptions, biases, values and the way that these affect our thinking

• That those preconceptions and values mean that any interferences are within a certain context

• Ambiguity—that there may be more than one solution or more than one way to solve a problem

Critical Thinking implies:

• That there is a reason or purpose to the thinking, some problem to be solved or question to be answered

• Analysis, synthesis and evaluation of information ← 5 | 6 →

Critical Thinkers:

• Can approach something new in a logical manner

• Look at how others have approached the same question or problem but know when they need more information

• Use creative and diverse ways to generate a hypothesis, approach a problem, or answer a question

• Can take their critical thinking skills and apply them to everyday life

• Can clarify assumptions and recognize that they have causes and consequences

• Support their opinions with evidence, data, logical reasoning, and statistical measures

• Can look at a problem from multiple angles

• Can not only fit the problem within a larger context but decide if and where it fits in the larger context

• Are comfortable with ambiguity (www.bcc.ctc.edu/lmc/ilac/critdef.htm)

THE ROLE OF CRITICAL THINKING IN THE PROMOTION OF SOCIAL JUSTICE

One of the most important functions of a relevant educational pedagogy (philosophy of teaching) is to confront social injustice and environmental destruction with some meaningful and relevant questions. Some philosophers have suggested that the notions of what is right or wrong are already within us. We begin as children questioning simple fairness. In adulthood, we look at right and wrong as more complex questions, with answers other than simply yes or no.

As David Jardine (2000) has shared in his book Under the Tough Old Stars, the word “educate” derives from the Latin root educatus: to bring out or to rear (raise). We take this meaning literally to state that we, as educators, are helping to develop, or to bring forth, the whole collective of body, knowledge, mind, soul, and character within our students. The important questions are within us and stem from the life experiences we have lived with our families, our friends, and our foes. What burns inside our students, the future teachers, are the questions of meaning-making and the discovery of truth. When we present real questions to our students, relevance and meaning-making enhance our perspectives and help us to feel worthwhile.

Conversely, our disaffected (at risk or turned-off ) students are overloaded with frustrations, and they often display a refusal to learn or even look inward. In the book “I Won’t Learn from You”, Herb Kohl (1994) called this phenomenon (refusing to learn) “creative maladjustment.” Could a student’s refusal to learn also stem from her inability to create questions of real personal and social relevance? That often our students are frustrated by a lack of personal power and disconnected from the real issues of their time may be the logical consequences of an educational system that has been imposed upon them by distant leaders and policy makers. Educational and social change begins with the questioning of the ideas that have maintained a broken system in which many of our students fail. In our culture, we need individuals who dare to come forward to question the big problems such as: “Why do we continue to wage wars outside our borders?”; “How can we judiciously resolve the issue of 12.5 million illegal aliens living in our country?”; “How can we allow such large numbers of our students to fail or drop out of high ← 6 | 7 → school?”; and “Why are we failing to correct the achievement gap between minority and poor students and their white and affluent classmates?” These are just some of the critical questions.

From John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance” to Eminem’s “Feel the Love” to John Mayer’s “Waiting for the World to Change,” the call is for real pedagogical changes: to question the boredom and the alienation brought on by teachers and schools that perpetuate policies of social reproduction. We cannot continue to operate schools that foster failure through poor educational practices. The new psychological and educational knowledge required to facilitate human growth and learning should be a primary focus of today’s teacher. How we can enliven a passion for discovery and teach relevant learning processes with critical questioning is one of the keys to creating classrooms that match the requirements of today’s youth.

Technology and related information-age advancements have changed our world in many ways (Peters, 2006). Knowledge and new information emerge from academic, business, and private organizations with such speed and volume that the total amount of info-data/knowledge available far exceeds anyone’s capacity for comprehension. Even the processes we are using for the creation of this book may become obsolete within a short period.

As you read this book, assuming you are holding a hard copy, the 5,000,000 books in print are being electronically copied to supplant and possibly to replace actual hard-copy manuscripts. This act symbolizes the dynamic growth of information and communication technologies (ICTs). As our world continues to “shrink,” a factoid’s value will diminish, too. What this implies for educators is that learning as a process of thinking and evaluating new information is much more important than rote memorization. Of course, the need to learn facts will continue to be of value; however, its importance is of diminished significance in comparison to one’s ability to assimilate new information and to accommodate that information in relation to this rapidly changing world. This process-driven quest for learning is inspired and enlivened by critical questioning.

HOW TO CREATE CRITICAL QUESTIONS

Changes in technology call for a re-examination of old paradigms of critical thinking and beg the development of new behaviors to execute pathways for understanding our role within these new ICT defined cultures (Peters, 2006). Thinking critically will be key to one’s ability to negotiate life’s chaotic and confusing constellation of choices. Because of the importance of this skill, thinking, it is important for students to begin to build understanding of the ways one develops critical questioning skills and dispositions. For purposes of applying educational psychology, you, as a student/teacher, can implement the processes of critical thinking for every developmental level from emergent critical thinkers (pre-school) to fully matured critically thinking citizens (college graduates?).

One of the many markers of the educated person is the ability to think critically. This activity, critical thinking, is associated with informed query (questioning) and concomitant intellectual attributes, including linguistic facility and research-based knowledge foundations. When these attributes are linked with an attitude or disposition of inquisitiveness characterized by honest curiosity (versus a haughty snobbishness defined as hubris), the quality of interaction is markedly higher. Critical thinkers are lively discussants at political events, participants in positions of community leadership, or situated within academic communities as professors or students. Supporting traditions of discursive activity has been a primary function of the academy, the name given to all members of institutions of higher learning. Interactions between academy members (for example, dialogues ← 7 | 8 → and published papers) are opportunities for publicly displaying and testing research and newly developed ideas. In fact, the tradition of dialogue is older than the academy. As an example, the Meno, Plato’s dialogue of virtue, pre-dates the inception of academic institutions such as the university.

Historically, the activity of critical thinking is foundational to the Western tradition of intellectual endeavor. Most scholars would concur that Socrates (father to the Socratic method) taught us all to further our investigations into truth and knowledge until we answered the questions fundamental to our being, such as “What is virtue?” “Can virtue be taught?” In the ancient Greek dialogue Meno, Socrates seeks to find the answer to how virtue connects to humans (Phillips, 2006). His explorations in search of an answer lead him to question Meno as to the nature of education and knowing. How do we come to know virtue?

| SOCRATES: | And thus we arrive at the conclusion that virtue is either wholly or partly wisdom? |

| MENO: | I think that what you are saying, Socrates, is very true. |

| SOCRATES: | But if this is true, then the good are not by nature good? |

| MENO: | I think not. |

| SOCRATES: | If they had been, there would assuredly have been discerners of characters among us who would have known our future great men; and on their showing we should have adopted them, and when we had got them, we should have kept them in the citadel out of the way of harm, and set a stamp upon them far rather than upon a piece of gold, in order that no one might tamper with them; and when they grew up they would have been useful to the state? |

| MENO: | Yes, Socrates, that would have been the right way. |

| SOCRATES: | But if the good are not by nature good, are they made good by instruction? |

| MENO: | There appears to be no other alternative, Socrates. On the supposition that virtue is knowledge, there can be no doubt that virtue is taught. |

| SOCRATES: | If virtue was wisdom [or knowledge], then, as we thought, it was taught? |

| MENO: | Yes. |

| SOCRATES: | And if it was taught it was wisdom? |

| MENO: | Certainly. |

| SOCRATES: | And if there were teachers, it might be taught; and if there were no teachers, not? |

| MENO: | True. |

| SOCRATES: | But surely we acknowledged that there were no teachers of virtue? |

| MENO: | Yes |

| SOCRATES: | Then we acknowledged that it was not taught, and was not wisdom? |

| MENO: | Certainly. |

Socrates may well have believed that teaching was truly the way in which virtue was acquired, but his method of teaching was to push others to deeply investigate each question. As we seek to apply this process of developing critical questions in our classes today, we are fortunate to have had ← 8 | 9 → a series of mentors following these lines of query and refining the applicability to meet the changing needs of our students and the world they inhabit. Socrates, though important in the tradition of Western thought, is of note historically. Bringing the concepts forward 2,000 years, perhaps Bob Dylan, Mary Oliver, 50Cent, Tupac, or other members of hip-hop or other cultures would frame it better for the youth of today (White, 1997).

As an example, let us critically look at questions of virtue from some of these more current challenges of mainstream thinking: Mary Oliver and Tupac Shakur. Mary Oliver is a widely anthologized American poet who lives in Provincetown, Massachusetts. She grew up in eastern Ohio, and as a young woman, she summered in the woods of western Pennsylvania in a place called Cook Forest. Living in an old army tent, she would imagine herself a poet, and she spent her time as a flâneur: an idler. She would roam the forest in search of herself, and she used the time to observe nature’s beauty and man’s destruction. Years later, she would write The Wild Geese, the poem that won national attention and admiration.

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to crawl through

the desert for a hundred miles

repenting. You just have to let that

soft animal in yourself love what it

loves.

This poem frees; it liberates. Reading this brings back our childhood and the time of our freedom from oppression of schedules, responsibilities, and obligations. It relates to our work as educators, but how does it connect? What rules do you need to adhere to and what callings do you answer?

Tupac Shakur grew up in the shadows of America’s 1960s. His mother, Afeni Shakur, was a Black Panther, and Tupac’s life was just starting as the civil rights movement had achieved national attention. The hope and the frustration of civil rights failed promises left Tupac as a ten-year-old proclaiming: “I want to be a revolutionary!” (White, 1997). Tupac took this calling and transformed himself into an icon of hip-hop. His lyrics were both a rant and raging against a world of racism and discrimination of the black man. The words of his songs were also an appeal to bring the changes necessary to free oneself of the oppression of the hood:

We gotta make a change. . . .

It’s time for us as a people to start makin’ some changes.

—2PAC Lyrics “Changes”

Tupac challenges us to look at the injustices of the inner city and to feel the pain of ghetto traps: pimps, drugs, violence, and alienation. Tupac calls to his brothers and sisters to examine the situation they find themselves in and to adjust their lives before the violence changes them. Unfortunately, Tupac was a victim of his own prophesies. On September 13, 1996, in Las Vegas, Nevada, Tupac Shakur died from gunshots inflicted upon him six days earlier (White, 1997).

However, his lyrics live on as a reminder of the continuing need to “make a change.” As future teachers, you are in a unique position to ask questions of your own. What role will you play in the production of social change? As a teacher, what aspects of social change do you want to incorporate within your classroom? Do the women’s movement, civil rights, democratic processes, students with disabilities, and care for the environment have a place within your curriculum or classroom culture? ← 9 | 10 →

For the authors of this book, the dynamic and pressing issues of social change and the problems associated with our modern civilization’s ecological mismanagement are drivers of our motivation to increase the critical thinking capacity of our students. We take inspiration from the mentor to many subscribers of critical thinking: a man named Paulo Freire (1970). Freire’s work has ignited a new political revolution in American educational dialogue (Goodman, 1999; Kincheloe & Steinberg, 1997; McLaren, 1997). Informed by Freire’s thought and word, educators for social justice are inspired to have hope for the future through Freire’s critical pedagogy: the pedagogy of love. Love in Freire’s eyes was a love for humanity. This love is not a romantic love, but a mindful compassion and connectedness with all people to create successful communities. Successful communities, in Freire’s eyes, were ones in which all citizens could read, develop personal agency, and safely co-exist in an atmosphere of collective harmony and social justice.

Following the loving legacy of Paulo Freire, we feel a responsibility to prepare our students for the world of diversity and the demands of proper earthly stewardship. Helping to prepare future teachers of yet unborn generations of citizens makes the issues of critical thinking and its application into a real and relevant problematic not a solitary, esoteric, or academic exercise. Critical thinking and questioning will make your classroom come alive!

Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy is deeply imbedded into the practice of the teaching. His teaching has given us a sense of personal responsibility that motivates and guides us to help our students to work toward issues of social justice and to confront problems of our environment. These important activities require thinking that is critical and well informed. Freire’s goal was to bring literacy to an illiterate and exploited mass of millions of Brazilians. By forming literacy circles, he applied social learning theory to support individual learning. The result was the creation of literacy for thousands of Brazilians (McLaren, 2000).

CONSTRUCTIVIST ACTION LEARNING TEAMS

From Freire, I have taken the notions of critical pedagogy and literacy circles and created a process called Constructivist Action Learning Teams (CALT). Constructivist theory comes from the work of developmentalists Jean Piaget and his contemporary, Lev Vygotsky. These men affirmed our ability to create and construct our own lives through the multifaceted and experientially based existence that we continuously evolve and participate in. We are the agents of our own destiny. This agentic process posits people as the essential creators of their own life experience. Students’ experiences contain relationship choices, activity decisions, and learning opportunities. Constructivists believe that individuals re-structure the chaos of life to create meaning and order within their own worlds. In this model, teachers provide stimulation, guidance and extrinsic motivation in order to maximize the intrinsic motivation of our students and to help them to further their understandings and knowledge.

In the CALT process, I begin by teaching my students about framing critical questions. This teaching includes a rationale for using critical query. Critical query reflects the knowledge of the conversationalist, and it furthers the discussion beyond simple reductive yes and no questions. Questions and their quality do reflect upon the individual, and there are, contrary to popular wisdom, “stupid” questions. Questions like, “Is our children learning?” (Begala, 2000) reflect extraordinarily dim light upon the interrogator. I want my students to get beyond the reductive “Yes” and “No” conversant critique and to move the conversation deeper into an intellectual and informed discussion. ← 10 | 11 →

How to achieve this higher learning is no mystery. The information and grist for the student’s mental mill are located within the research of the topic at hand. Using the common research forms contained within the literature review process, the students will find information and fact to bring meaning to their questioning. Within the books, journal articles, and myriad other sources of information, students will find facts (or untruths) upon which they can build questions and arguments for discussion.

Adolescents are known for their developmentally linked, reductive, either/or thinking. As adolescents mature in their ability to define their world, they begin to eschew perceptions of either/or. As college students, it is incumbent upon you, as emerging adults, to see that overgeneralizations are invalid and that the answers to important questions are not “Yes” or “No,” but are complexities of response belonging rightfully upon a continuum ranging widely across a spectrum of culturally driven and diverse possibilities. Questions like, “As a nation, what policies should we develop to reverse global warming?” are not answered with simple solutions.

The writers of this book want you to share in the knowledge contained in the readings we have selected for your edification. Some of these readings are deep, and some of them are easy to comprehend. However, all of these readings are made meaningful by your thinking about the reading’s content and by developing critical questions to make their investigations more enlivened and experiential.

Related to each chapter assignment in the classes I teach, I ask my students to create a critical question and to bring it to class with them. At the end of my lecture, I ask the students to query their peers with their question and to spend some time in discussion. What I get from this process is an enthusiasm and a participation that is lively. The students enjoy each other’s company, and they like having the ability to share their opinions and to challenge their learning. Topics such as racism, discrimination, poverty, No Child Left Behind, hip hop culture, and other relevant issues spark a dialectical discourse that makes the traditional, teacher-directed questioning pale in comparison. In my classroom during CALT, the noise level picks up and the interaction is healthy and enlivened. I believe that higher levels of learning are accomplished through the CALT process and the use of critical pedagogical practices.

College is a time of great intellectual and emotional growth. However, the greatest purpose of college may be in the social learning that can occur within the classroom and throughout the campus community. Learning how to work with diverse student groups and to develop dispositions that foster successful team working skills can be among the most beneficial tools one can acquire during the college years. Using the CALT process helps students stretch themselves and ask the tough questions. Students like to challenge each other’s thinking and to investigate multiple pathways for solving problems. Hopefully, by building positive cultures of learning and fostering values of respect for diversity (of opinion, personality, style, etc.) within our classrooms, we can help our larger university community and extend these pro-social behaviors for everyone’s benefit.

THE REAL QUESTIONS

Carlos Santana demands, “Give me your heart, make it real, or else forget about it.” It is time to “make it real” in the classrooms. Our students have been mesmerized into boredom with the traditional curricula of sterilized textual representations of cultural reproduction. The frontier of education and the point of adventure and excitement are within working through problems of the present moment to meet the challenge of preparing our students for the future. Valid questions for today’s students confront inequalities and alienation from hope of ever changing our culture. John Mayer sings, “We’re ← 11 | 12 → waiting…waiting for the world to change.” But if all we are going to do is wait, the world is never going to change in a direction other than the direction corporate and political leaders choose for their profit. Building more fences around our nation’s borders and producing gated communities to surround our suburban estates changes nothing of the inequality or alienation most Americans experience. Instead, we need our future citizen/leadership to ask, what can I do to stop the violence in my communities? What are the real reasons for drug use of epidemic proportion in this country? What is wrong in our communities that gangs are viable social units? How can I work to stop the spread of sexually transmitted diseases? When will our schools stop focusing on standardized assessments of the past with no plans to prepare students for a future? When will we experience a real and meaningful connection with our earth instead of viewing it as an object to be trashed and exploited? These are examples of the types of questions students of a critical constructivist educational psychology need to ask themselves in preparation for teaching today’s youth.

Questions of social justice and personal relevance are the critical problems to examine if we want to make a difference in the lives of those we teach. Until we engage our students in the types of real questions that need confrontation, the process of education will work to reproduce the same alienated, disconnected, mind-numbed citizens who are unprepared to find solutions to the vexing social and political questions of our time. It will not be their fault that they cannot see the solutions, because they were tacitly taught to deny their complicity and to blame or ignore the victims of social malaise. Just like the miscreants at school, society shoves misfits aside and attempts to coerce them back to work (Goodman, 1999). Meanwhile, in other locations, the shootings continue; the drug cartels have a lucrative market for their goods; and the criminal justice system finds work for the unemployed. These are the real, present issues that need questioning, and the indignation of young people is the fuel for possibility and change.

The leadership in the teaching of educational psychology must ask: what are our social and professional responsibilities as educators? The root of the word psychology…psyc…comes from the Greek word “psyche.” Psyche means “soul,” and it also, in psychiatry, means “mind.” The mind is “an organic system reaching all parts of the body and serving to adjust the total organism to the needs or demands of the environment” (Friend & Guralnik, 1953, p. 1175). If our soul is our essence, then we need to consider questions of essential importance to the education of our future citizens. As the children of Birmingham, Alabama, seized the day and left the schoolhouse for the jailhouse to force the end of segregation, we need to bring the spirit of the civil rights movement back to our classrooms and communities needing equally important transformations. Teaching our youth how to develop critical questioning may allow their minds to develop the congruence and courage to empower greater social changes.

REFERENCES

Begala, P. (2000) “Is our children learning?” The case against George W. Bush. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., & Cooking, R.R., Editors. (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, D.C., National Academy Press. http://newton.nap.edu/html/howpeople1/ch1.html

Details

- Pages

- XX, 707

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433141638

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433141645

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453912799

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433124495

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1279-9

- Language

- English

- Keywords

- Education Psychology Critical Pedagogy language acquisition motivation ecology learning education Pädagogische Psychologie

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 707 pp., num. ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG