Anna Haag and her Secret Diary of the Second World War

A Democratic German Feminist’s Response to the Catastrophe of National Socialism

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Fragments of History in the Raw

- Chapter 1: Paradigms of Creativity and Marriage with an Educational Mission

- Chapter 2: Fighting for the Fatherland: Sacrifice, Resilience and Loyalty Betrayed

- Chapter 3: Republican Values, Female Agency and the International Peace Campaign

- Chapter 4: Responses to Hitler’s Seizure of Power: A Purely Masculine Affair?

- Chapter 5: The People’s War: Diarists, Demagogues, Spin-Doctors, Popular Broadcasters and Secret Listeners

- Chapter 6: False Ideals: Master Race, Religious Mission, Faith in the Führer, Tainted Healthcare and Perverted Justice

- Chapter 7: Avalanche: Super-Criminals, Yellow Stars, Deportations, Plunder, Slaughter – and the Spectre of Poison Gas

- Chapter 8: Echoes of Stalingrad and Un-German Attitudes: Women’s Responses to Total War

- Chapter 9: Cities Razed to the Ground and Calls for Resistance: Can You Kill Hitler with a Cooking Spoon?

- Chapter 10: Matrix of Democracy: The Diarist’s Political Vision

- Epilogue: The Legacy of a Swabian Internationalist

- Chronology

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Figure 1: Anna and Albert Haag (around 1909)

Figure 2: The Schaich Family, showing Anna as a child (around 1896)

Figure 3: Anna Haag checking a typescript (mid-1920s)

Figure 4: Anna and Albert Haag with their three children (around 1930)

Figure 5: Anna and Albert Haag (1933)

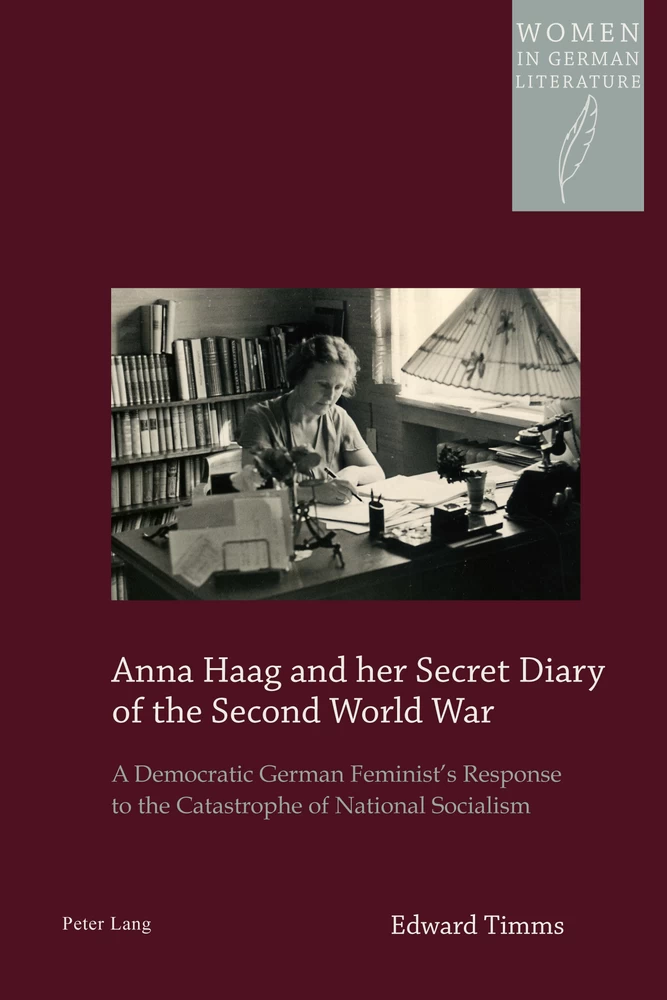

Figure 6: Anna Haag at her writing-desk in the mid-1930s

Figure 7: ‘On the Orders of the Reich Propaganda Directorate’ (August 1941)

Figure 8: ‘Three Criminals Executed’ (June 1942)

Figure 9: ‘Remember your Warriors’ Graves in Foreign Soil’ (collage, March 1943)

Figure 10: (a): ‘The Ghetto in Luck’, pasted-in press cutting; (b): Hitler with his generals, pasted-in photograph (December 1942)

Figure 11: Echoes of Stalingrad: rumours and official report (January 1943)

Figure 12: ‘[Roose]velt’s Global Supremacy’, from the Stuttgart NS-Kurier (8 May 1943)

Figure 13: ‘… what about us women?’ Cover of pamphlet by Anna Haag, 1945. Stuttgart: Liga gegen den Faschismus.

Figure 14: Anna Haag (after 1945) ← xi | xii →

Figure 15: Albert Haag (after 1945)

Figure 16: Family group in King’s Norton, 1947

Figure 17: Anna pictured with Esther McCloy at the inauguration of the Anna-Haag-Haus, 1951

Figure 18: Anna-Haag-Haus, 1961

All illustrations are reproduced with the permission of the Anna Haag Estate.

My interest in diaries as a historical source was kindled by an international conference entitled ‘Dear Diary: New Approaches to an Established Genre’, hosted by the University of Sussex in autumn 2001. My primary focus, as Director of the Centre for German-Jewish Studies, was on diaries by Jewish victims of Nazi persecution, notably Anne Frank, Victor Klemperer and Etty Hillesum. At that stage, I was only dimly aware of the significance of anti-Nazi diaries written by ordinary Germans as a historical source.

My Sussex colleague Sybil Oldfield had once mentioned that her grandmother, a democratic German pacifist, had kept a diary while living in Stuttgart during the Second World War. ‘What ever happened to your grandma’s diary?’ I asked one day. ‘It was deposited at the Stuttgart City Archive’, she replied. But a few days later she appeared at our house in Brighton carrying a bulky package. ‘Look what I’ve found in the wardrobe!’ she exclaimed. It was the 500-page carbon copy of a typed transcript from the original diaries, covering the years 1940 to 1945, prepared by Anna Haag for publication after the Second World War. Since no publisher could be found for such an unsparing chronicle of everyday life during Germany’s darkest years, the typescript had been gathering dust for almost seventy years.

As I began leafing through those flimsy fading pages, I was completely captivated. Here was a woman diarist whose entries evoked the trauma of surviving the Nazi regime and the Allied air bombardment almost as evocatively as Klemperer. What an extraordinary discovery! As I collected the information needed to frame a systematic account of the diaries, it became clear that such a study would require visits to the Stuttgart City Archive, where Anna Haag’s original diaries from the years 1940 to 1945 are preserved, together with the top copy of the typescript. This would be a formidable obstacle for an author partially disabled by progressive Multiple Sclerosis.

Fortunately, the University of Sussex student employment website came to my aid, putting me in touch with a gifted and enthusiastic bilingual ← xiii | xiv → research assistant named Jennifer Bligh, then a graduate student from Germany, now a professional journalist based in Tel Aviv. With characteristic energy she travelled to Stuttgart to undertake the essential archival research. She also visited and interviewed members of the Haag family. After obtaining the consent of Sabine Brügel-Fritzen, representing the Anna Haag copyright, she visited the Stadtarchiv and scanned the complete sequence of twenty handwritten diaries, including the pasted-in press cuttings that enhance their documentary authority.

At my home in Brighton I now had access both to the carbon copy of the typescript (in a large red shoe-box) and to the twenty-volume handwritten originals (electronically on screen). This facilitated the double focus on both original manuscript and typescript variants that shapes the present book. Passages cited from the handwritten originals, identified by the abbreviation (HA) to distinguish them from the post-war typescript (TS), have been deciphered with Jennifer’s help and systematically translated. The English versions cited in the text have been carefully correlated with the German originals, which are incorporated in endnotes.

Completion of this book would not have been possible without the help of other allies, especially members of Anna Haag’s family, who have enthusiastically encouraged my research. Drawing on a wealth of personal memories, her son Rudolf Haag gave the book his blessing, after arranging for friends to read aloud the whole sequence of ten chapters to him (Professor Haag, an internationally renowned theoretical physicist who had lost his sight, died on 5 January 2016 at the age of ninety-three). Draft chapters have also been read, re-read and amended by three of Anna’s grandchildren: Sybil Oldfield, who has been tireless in her support; Sabine Brügel-Fritzen, whose copy-editing skills have enhanced the text; and Michael Mence, who shared both personal memories and valuable documentation.

The writings of Anna Haag, including her diaries, are copyright The Anna Haag Estate. All enquiries should be addressed to Sabine Brügel-Fritzen (Germering). Email: sabine_bruegel@yahoo.de.

Thanks are also due to the Haag family for allowing me to publish a series of photographs documenting Anna Haag’s career. My friend and colleague at the University of Brighton, Julia Winckler, has kindly prepared the whole sequence of illustrations for publication. Further friends have gone ← xiv | xv → out of their way to check archival sources on my behalf: Fred Bridgham, who photocopied documentation at both the British Library and the Wiener Library in London; and Peter J. Appelbaum, who made available to me transcripts from the First World War diary of Rabbi Aron Tanzer.

The Peter Lang Verlag in Oxford has expedited the completion of the book by accepting it for publication well before the first chapter was written. Both the series editor Helen-Watanabe O’Kelly and the commissioning editor Laurel Plapp have been consistently supportive. Finally, heartfelt thanks are due to my wife Saime Göksu, who has acted as a sounding board throughout the writing process, responding as always with shrewd comments and constructive criticism.

Introduction: Fragments of History in the Raw

‘The contemporary witness is the enemy of the historian’, observed our sceptical visitor from Berlin, Professor Wolfgang Benz. We were discussing at Sussex the unreliability of reminiscences recorded many years after the event. ‘But personal testimonies with an authentic dateline are especially valuable’, was my reply. In my hands was the diary kept by a German-Jewish schoolboy named Ernst Stock in Paris during the spring of 1940, recording the panic as the Wehrmacht broke through French defences.1 Testimony of this kind helps historians to capture the immediacy of events, provided they follow the fundamental principle of diary research: back to the manuscript! By this means the authentic diary can be distinguished from various forms of ‘diary memoir’, composed at a later date on the basis of pre-existing notes. Diaristic narratives of indeterminate origin often make compelling reading, but – as Professor Benz noted in his introduction to the ‘Aufzeichnungen’ of another German-Jewish refugee, Hertha Nathorff – they contain reconstituted elements that are ‘not in the strict sense a diary’.2

Handwritten diaries are time capsules that register impressions of a specific moment from a clearly defined angle in a concise historical format. In the words of Myrtle Wright, a Quaker who chronicled her experiences in Norway under the German occupation, the authentic diary entry is ← 1 | 2 → ‘a fragment of history in the raw’.3 Of course we must beware of what Alexandra Zapruder (defining wartime diaries as a genre in her anthology Salvaged Pages) calls ‘the romantic illusion of these diaries emerging whole and unblemished from the past’.4 There is always a tension between a manuscript and its publication with the attendant editorial filters, and diaries can be touched up retrospectively to enhance the author’s self-image. But diary entries actually written during the Third Reich by writers determined to think for themselves constitute acts of resistance, articulating individual dissent from the perspective of an excluded minority. It is not by chance that the most widely read work of the Second World War is the diary of Anne Frank, which combines historical authenticity with imaginative flair.5

Diaries from the Second World War carry special weight for historians. Beneath the barrage of patriotic propaganda they reveal what ordinary people were thinking at the time. The diary-orientated approach to social history, pioneered by Angus Calder in The People’s War (1969), has been applied with growing sophistication by recent scholarship. For historians of everyday life in the Third Reich the trend received a further impulse from the publication in 1995 of the diaries of Victor Klemperer. As a German Jew who had taught at the Technical University in Dresden, Klemperer was saved from deportation by his marriage to an ‘Aryan’ wife. His diaries chart an ideological battlefield in which the discourse of European humanism is deployed against the debased language of the Third Reich, yielding compelling insights into the ‘forgotten everyday life of tyranny’.6 ← 2 | 3 →

Klemperer’s diaries are repeatedly cited in the history of The Third Reich by Richard J. Evans and the study of Nazi Germany and the Jews by Saul Friedländer. This signalled a qualitative shift as the historian’s narrative is brought down to earth and humanized. Highlighting the value of the ‘voices of diarists’ in the introduction to his second volume, Friedländer observes: ‘By its very nature, by dint of its humanness and freedom, an individual voice suddenly arising in the course of an ordinary historical narrative of events such as those presented here can tear through seamless interpretation and pierce the (mostly involuntary) smugness of scholarly detachment’.7

The diary is the most intimate of narrative modes, offering scope for intense self-reflection. To reach out to a wider audience the writer must bridge the gap between the private and the public spheres, a particularly challenging task under the pressures of a totalitarian regime. Under such conditions, keeping a diary may become a means of emotional survival, as a study of women confronting the Holocaust has shown: ‘Putting the situation in words empowers the victim, because her voice breaks the stillness of apocalyptic destruction. At the same time, the word that shapes reality endows a sense of control that distances the horror’.8

In studying the diaries of ordinary Germans we are faced with different variables. How was it possible for a nation of well-educated citizens and outstanding cultural achievements to support a regime that made it a crime to think for yourself? This was the key question for the Stuttgart-based author Anna Haag (1888–1982), the democratic feminist and pacifist who forms the subject of the present book. Like Klemperer, she found ways of weaving into her diaries an analysis of propaganda, pinpointed by revealing snippets of conversation. Indeed, she goes further by giving her commentary a gendered focus, challenging the cult of tough-minded masculinity that sustained the Nazi regime. ← 3 | 4 →

Anna Haag’s findings deserve special attention because her diaries, secretly written during the years 1940–5 in twenty notebooks now preserved at the Stuttgart City Archive, remain virtually unknown. Initially concealed in the cellar to avoid detection, they were later buried at Meßstetten in the Swabian countryside. After the war, assisted by her schoolteacher husband Albert, Anna Haag prepared for publication a transcript running to over 500 typewritten pages, but no publisher could be found for her unsparing account of the darkest days of modern German history. When a volume of her memoirs appeared in 1968 under the title Das Glück zu Leben (The Happiness of Being Alive), only thirty pages from her war diary were included. A further selection was added when an expanded edition of her memoirs was published after her death by her son Rudolf Haag.9

The initial research for this book focused on the 500-page typescript, a copy of which has been deposited at the University of Sussex. It soon became clear that a scholarly account would also require access to the handwritten originals. ‘Back to the manuscript!’ is easier said than done for an author whose mobility is impaired by Multiple Sclerosis. Fortunately, through the Student Employment website of the University of Sussex, it proved possible to enlist the help of a gifted bilingual research assistant, Jennifer Bligh. During a visit to the City Archive in Stuttgart she was able to scan all twenty handwritten diaries, including the numerous newspaper cuttings that Anna Haag pasted into the notebooks, together with loose-leaf letters.

Now that the manuscript is available for research in electronic format, it becomes possible to take account of variants between the two versions, measuring the compressed post-war typescript against the cornucopia of handwritten originals. A pioneering study by Britta Schwenkreis, published in the Backnanger Jahrbuch in 2005–6, provides an overview of the manuscript’s principal themes. However, it is misleading to suggest that the work was only slightly shortened when the typescript was prepared ← 4 | 5 → for publication.10 The handwritten diaries, including the insertions, run to over two thousand pages.

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 268

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035307993

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035397604

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035397611

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034318181

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0353-0799-3

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (January)

- Keywords

- anti-Nazi diaries analysis of propaganda Democratic German feminism everyday life in the Third Reich Hitler's seizure of power

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2016. XVI, 268 pp., 2 coloured ill., 18 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG