Areal Convergence in Eastern Central European Languages and Beyond

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- About the editors

- About the book

- Citability of the eBook

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- Does Verb Valency Pattern Areally in Central Europe? A First Look

- Central European Languages as a Complex Research Issue: Summarising and Broadening the Research Foci

- Prepositions in the Melting Pot: High Risk of Infection. Language Contact of German in Austria with Slavic Languages and Its Linguistic and Extra-Linguistic Description

- Variation in Case Government of the Equivalent for the Cognitive Verb to Forget in German in Austria and Czech

- Remarks on the Development of the Czech Modality System in Contact with German1

- Linguistic Areas in East-Central Europe as the Result of Pluridimensional, Polycentric Convergence Phenomena

- Loanwords in Bulgarian Core Vocabulary – a Pilot Study

- On Different Ways of Belonging in Europe

- Burgenland Croatian as a Contact Language

- Variation im Spracherwerb von Verben bei bilingualen Kindern (Russisch ‒ Deutsch)

- Hungarismen im Gemeindeutschen, österreichischen Deutsch, ostösterreichischen Dialekt und im Slawischen

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

Agnes Kim

University of Vienna

Anna Tetereva

Humboldt University Berlin

Emmerich Kelih

University of Vienna

František Martínek

Charles University/Prague

Ivan Šimko

University of Vienna

Jerzy Gaszewski

(ORCID 0000-0002-9313-6454)

University of Wrocław

Jiří Januška

Charles University/Prague

Luka Szucsich

Humboldt University Berlin

Nataliya Levkovych

University of Bremen

Sebastian Scharf

Humboldt University Berlin

Stefan Michael Newerkla

University of Vienna

Tamás Tölgyesi

University of Vienna

Thomas Stolz

University of Bremen

Uliana Yazhinova

Humboldt University Berlin

Viktoria Naukhatskaia

Humboldt University Berlin

Luka Szucsich, Agnes Kim, Uliana Yazhinova

This volume assembles written versions of contributions presented at a workshop organized at the Slavic Department of the Humboldt University Berlin. The workshop was conducted within the project Areal Convergence in Eastern Central European Languages (ACECEL), which was part of the CENTRAL network (Central European Network for Teaching and Research in Academic Liaison). CENTRAL was initiated by the Humboldt University Berlin and founded together with the Universities of Vienna and Warsaw, Charles University Prague as well as ELTE Budapest with the goal to establish joint projects for the promotion of exchange in research and teaching. All CENTRAL projects were funded by the German Academic Exchange Service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, DAAD) for four years (2015–2018).1 The primary goal of ACECEL was to investigate linguistic convergence in the languages of Eastern Central Europe which show many remarkable similarities. Luka Szucsich (Humboldt University Berlin) and Stefan Newerkla (University of Vienna) were the PIs of ACECEL which—at different stages—also included the involvement of colleagues in Prague, Warsaw and Budapest. The focus was put on a methodical and empirical component in the investigation of two or more languages in the context of possible language contact phenomena. The partner institutions with focusses in the field of lexical borrowing, in particular for German, Slovak and Czech (Slavic Department, University of Vienna) and in the field of morphosyntactic typology and microvariation in the field of Slavic languages (Slavic Department, Humboldt University) provided an ideal basis for cooperation for the described endeavors. The workshop—although still mainly focusing on Eastern Central Europe—took a broader areal perspective including larger parts of Europe, which is also reflected in some of the volume’s contributions (cf. Stolz/Levkovych, Šimko/Kelih and Tetereva/Naukhatskaia).

Languages of Eastern Central Europe and adjacent parts of Europe use a considerable amount of common vocabulary, which is certainly due to the transfer of loanwords during a long period of cultural contact (cf. the contributions of Newerkla, Šimko/Kelih and Tölgyesi). But they also share several interesting ←9 | 10→and distinct grammatical features ranging from (i) valency and government patterns (cf. Gaszewski, Kim and Kim/Scharf/Šimko), (ii) modality systems (cf. Martínek) and (iii) morphosyntactic patterns (e.g. doubly-filled-comp properties, prefixal verbal composition, purposive infinitival clauses, cf. Szucsich), to name just a few structural properties. Furthermore, Stolz/Levkovych investigate the distribution of belong-constructions in a broader European context. Last but not least, Tetereva/Naukhatskaia discuss the acquisition of verbs and verbal categories in Russian-German bilinguals.

Some of the contributions take up a diachronic (cf. Kim and Martínek) and/or a theoretical perspective (cf. Januška, Kim and Newerkla), discussing methodological as well as metalinguistic issues. One of the problems which is discussed in a lot of the papers of this volume, and which still remains unresolved is a clear understanding of the processes involved in language contact and how they may form what has been labelled a linguistic area.

Two of the papers published in this book (cf. Tetereva/Naukhatskaia and Kim/Scharf/Šimko) present results of two subsequent international cooperation projects funded by the CENTRAL network in 2016 and 2017, namely the CENTRAL-Kollegs Empirical perspectives on area-typological aspects of language contact and language change and From language contrast to language contact: Corpus linguistic approaches to language contact phenomena. This format for research based-learning aimed at junior researchers and students. Under the guidance of junior researchers, student research teams developed and carried out short-time research projects. The two above mentioned CENTRAL-Kollegs were both organised by Uliana Yazhinova (Humboldt University Berlin), Agnes Kim (University of Vienna) and Karolína Vyskočilová (Charles University Prague). Eight BA- or MA-students participated in each of them; two from Vienna, two from Prague and four from Berlin.

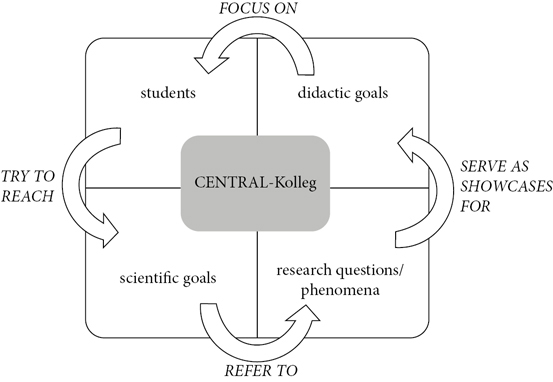

The main idea of the two abovementioned projects was (i) to create a framework within which the participating students could conduct their own research, and (ii) to bridge the gap between studying and research in Slavic linguistics. In order to facilitate these learning and research processes the organisation team equally pursued and connected didactic and scientific goals in both CENTRAL-Kollegs. The program was based on the so-called research competence model, which comprises two main components: (i) language contact and convergence as scientific objectives, and (ii) guided research and mentoring as teaching strategies. The main target was to guide the students throughout the whole research process as depicted in Fig. 1 and thus support them in developing linguistic and social competences to plan and conduct collaborative research projects and maybe even pursue a scientific career.

←10 | 11→The students collaboratively investigated selected language contact and convergence phenomena by employing recent corpus linguistic methods and thereby added to the research of the CENTRAL project ACECEL. Additionally, the projects as a whole contributed to the dissemination of up-to-date empirical methods in Slavic contact linguistics. Thus, we hope that this book represents a successful example of a collaborative endeavor brought about by senior researchers, junior researchers and students.

←11 | 12→←12 | 13→1 For more information on the network and its programs see https://www.projekte.hu-berlin.de/en/central/network/index_html.

Jerzy Gaszewski

Does Verb Valency Pattern Areally in Central Europe? A First Look

Abstract: The paper reports on the results of a pilot study of verb valency in Central Europe. The analysis relies on semantic roles associated with individual predicates, so-called microroles (Hartmann/Haspelmath/Cysouw 2014), and involves a comparison of the distribution of grammatical elements (cases and adpositions) marking the arguments corresponding to particular microroles. The degree to which the distributions of markers in certain languages correspond to each other is captured by means of a distance index, a simple statistical measure introduced in the paper. The results provide some support for Donaubund (represented by Czech, German and Hungarian), but also show general parallels among all the investigated languages.

Keywords: verb valency, argument marking, language distance measurement, linguistic areas, Danube Sprachbund

1 Introduction

Central European languages have been researched from an areal perspective for a considerable time. The field of areal linguistics itself is currently shifting away from determining whether “a given geographical area could be classified as a linguistic area or not” (Hickey 2017, p. 2) to describing particular areal patterns of language structure as such (cf. also Campbell 2017, and, with particular reference to Central Europe, Januška this volume). In this vein, I seek to investigate how one grammatical phenomenon, verb valency, patterns in the region.

The main objective of this paper is to give a preliminary answer to the question posed in the title, based on data from a pilot study.1 Apart from that, the ←13 | 14→paper aims to lay down the conceptual foundations which further research will inherit from the pilot study, with various improvements (cf. section 4.3). Thus, another objective of the paper is to present the project’s theoretical approach to the comparison of valency across languages (section 2.3) as well as the methods of data analysis (section 3.2).

The present paper deals with a limited group of five languages, chosen for the pilot study: Czech, German, Hungarian, Polish and Romanian. It is clear that the group must be broadened in later research (cf. section 4.3). The choice of languages was partly dictated by the availability of informants, but I also intended to obtain a graded sample of Central Europe.

The region has been variously delineated by linguists (overviews can be found, e.g., in Kurzová 1996, Newerkla 2000, Newerkla 2002, Pusztay 2015 and Januška this volume). The region has been referred to by different names as well. Central Europe is the most commonly used label, but we also encounter Donaubund, Carpathian Sprachbund (Thomas 2008 after Januška this volume), Mitteleuropa and Zentraleuropa in German-language sources, or Amber Road Region (Pusztay 2015). Usually a separate label is combined with a proposal concerning alteration of the membership or structure of the group. The different concepts will not be discussed at length here, the reader is referred to the works mentioned above. Among the many proposals, the most widely accepted seems to be the idea of a linguistic area encompassing Czech, Slovak, Hungarian and (Austrian) German as the core languages, with Polish, Slovenian and Croatian as marginal members. I will use the label Donaubund to refer to this grouping and Central Europe will be reserved for the broader region ranging from the Baltic Sea to the Balkans and from German-speaking countries to Russia.

The five selected languages represent different levels of established “Central Europeanness”. Czech and German are very often grouped together by areal studies and can be said to belong to the core of the region. Of the two, German has generally been a major superstrate throughout the region. Hungarian is also typically grouped with the former two languages, although it is genetically unrelated to them (or any of its neighbours).2 Any observed similarities ←14 | 15→involving Hungarian make a good case for areal convergence. The position of Polish is much more ambiguous. It is not always included in studies on Central Europe and it is never considered to belong to the core. Somewhat confusingly, it shares similarities on all levels of language structure and in the very form of linguistic units with Czech, which is due to a close genetic relationship. Common origin, the “default” reason for Czech-Polish similarities is a confounding factor for an areal study. I propose a way of controlling for this in the analysis (cf. section 3.4). Romanian, the last of the five languages, is geographically proximate, but typically grouped within the Balkan linguistic area and not Central Europe. It is included as an expected natural outlier. Apparently, Romanian is only ever considered together with Central European languages when Balkan languages in general are included in the given study. This is evident when one traces the few mentions of Romanian throughout the overview text by Januška (this volume).

Using such a graded sample of Central Europe, the extent of the region is consciously left underspecified. Ultimately, it is the data that will show how the languages of the region relate as far as verb valency is concerned. Consequently, the above description of the five languages and their status within Central Europe is only a point of reference, a picture we get from earlier research on the area, much of which does not even deal with valency.

Any language possesses hundreds if not thousands of valency structures. It is impossible to investigate all of them and, hence, selection of material is necessary. The choices made in the course of this selection are of great importance. However, there are no generally approved methods to obtain a sample of verbs of a language for a comparative study (cf. Haspelmath 2015, p. 134). The problem is addressed in full in Gaszewski (in preparation b). Here, it is sufficient to state that several broad groups of verbs are dispreferred in the study. The reasons for that are explained in section 2.2. The 75 verbal meanings selected for the pilot study are provided in Appendix 1.

The data was gathered in the form of example sentences from five people, each a native speaker of a different language. Informants are obviously only one of the possible sources of data on valency. The advantages and disadvantages of each type of source are discussed extensively in Gaszewski (in preparation a), the ultimate choice being to have informants as the main source of data throughout the project, with help from other types of sources whenever possible. In the pilot study the main benefit of informants was that they allowed the gathering of a substantial amount of data relatively quickly and easily.

←15 | 16→2 Valency and the Comparison of Valency

2.1 The Notion of Valency

Valency refers to the property of some lexical items (valency carriers) which require other items to co-occur with them to complete their meaning.3 In other words, valency carriers open slots (valency positions) to be filled by dependent words. Let us now analyse how this works in a single sentence.

|

(1) |

Kupiłem od sąsiada samochód za milion. (Pl, 2)4 |

|

buy.PST.M.1SG from neighbour.GEN car.ACC for million.ACC |

|

|

‘I bought a car from my neighbour for a million.’ |

The central element in the clause, the valency carrier, is the verb kupiłem (an inflected form of kupić ‘to buy, PFV’). It opens several valency positions filled by the phrases in the sentence, i.e., the arguments of the verb.5 They are: samochód ‘a car’ (the product bought), za milion ‘for a million’ (the price paid), and od sąsiada ‘from (a/the) neighbour’ (the seller). The last valency position is the buyer, the subject of the clause, expressed in (1) solely by the 1SG marking on the verb. An explicit subject is possible, but not necessary in Polish.

The whole structure consisting of the valency carrier and the dependent valency positions is called a valency frame.6 Note that the semantic roles above are defined with respect to a single predicate ‘to buy’. In accordance with the ←16 | 17→terminology of Hartmann/Haspelmath/Cysouw (2014), I will call roles at this level of specificity microroles.

Each argument realises a semantic role related to the meaning of the valency carrier. However, we are able to identify the arguments and interpret the clause correctly thanks to the morphosyntactic marking of the individual phrases, covered mainly by cases and adpositions in (1). These kinds of grammatical markers are especially prominent as means of marking arguments in the languages under scrutiny. They will, therefore, be main objects of analysis here. Naturally, valency may be marked in other ways too (e.g., head-marking, element order).

2.2 Valency in the Areal Perspective

It is worth asking to what extent valency is conducive to areal influence. Before we refer to sources considering the matter with regard to language structure in general, let us briefly focus on Central Europe. Some studies (e.g. Newerkla 2000, p. 11, Pusztay 1996 after Pilarský 2001, Bláha 2015, p. 156–157) see the parallel use of valency markers as an areal feature of Central Europe. Probable calques in the use of prepositions in non-standard varieties of German had been noted throughout the 19th century and collected by Schuchardt (1884; after Kim this volume). Such observations are promising from our perspective. By contrast, Pilarský (2001: 118) staunchly rejects the validity of parallels in valency marking among Central European languages. Yet, most of the contemporary studies quoted above (except for Bláha 2015) consider a very limited number of valency structures, and so a broader analysis appears necessary.

It should also be made clear that the phenomenon of valency is rich (cf. section 1) and not uniform. Many valency structures show high regularity within (and across) languages. This regular side of valency is transitivity. In other structures, the marking of valency positions is word-specific (lexically governed by individual valency carriers). The question underlying the discussion below is which aspects of valency are of primary interest for an areal study. The answer has implications for the choice of verbs to be included.

Tab. 1 shows two rankings of levels and elements of language structure according to the likelihood of being affected by areal patterns. Both rankings are very general and neither mentions valency explicitly. However, we can relate some points in the rankings to different types of valency structures. The marking associated with individual verbs is essentially idiomatic and we can link it with the “structure of idioms” at the top of Aikhenvald’s (2006) scale. Hickey (2017) puts “vocabulary” in the top position, but this point includes “phrases”, which allows us to link the same kind of valency structures with it.

Tab. 1: Rankings of elements and levels of language according to conduciveness to areal patterning

|

Aikhenvald (2006, p. 5) |

Hickey (2017, p. 6) |

|

more similar to neighbouring languages |

levels most affected [by areal influence (JG)] |

|

Structure of idioms |

Vocabulary (loanwords, phrases) |

|

Discourse structure |

Sounds (present in loanwords) |

|

Syntactic construction types |

Speech habits (general pronunciation, suprasegmentals) |

|

Core lexicon |

Sentence structure, word-order |

|

Inflectional morphology |

Grammar |

|

more similar to genetic relatives |

levels least affected [by areal influence (JG)] |

Note: The original vertical arrangement of Aikhenvald’s ranking is reversed here.

←17 | 18→Transitivity can be associated with items that are lower in the rankings: “syntactic construction types” (middle of scale in Aikhenvald’s ranking) and “sentence structure” (below the middle point on Hickey’s scale). The regular side of valency is thus less likely to show areal influence.

This affects a significant number of verbs. Both plain intransitives (monovalent verbs with the marking of the sole argument predictable from the language’s general alignment type) and plain transitives (bivalent verbs with similarly regular marking of arguments) appear to be of little interest for our study. Another reason to exclude such verbs is directly related to our selection of languages. In both classes of verbs we can expect massive convergence in Central Europe since all languages of the region have nominative-accusative alignment.7 As has been said, however, this similarity is completely uninformative since this alignment type prevails not only in the region and not only in all of Europe. It is the most common type in the world (Nichols 1992 after Koptjevskaja-Tamm 2011, p. 579).

There is one more group of verbs that ought to be excluded from our choice of verbs. I will illustrate the problem with German examples.

|

(2) |

Ich warte auf meinen Papa. (G, 5) |

1SG wait.1SG for my.M.ACC dad.M.ACC |

|

|

‘I’m waiting for my dad.’ |

|

(3) |

Ich stelle das Glas auf den Tisch. (G) |

|

1SG put.1SG the.N.ACC glass on the.M.ACC table |

|

|

‘I’m putting the glass on the table (in a standing position).’ |

The last phrases in both (2) and (3) have the same marking, i.e., auf + ACC. However, the rules of the marking are different. The verb warten ‘to wait’, as in (2), consistently combines with auf + ACC for one of its arguments. By contrast, the verb in (3), stellen ‘to put (in a standing position)’, can combine with various spatial prepositions. The one used in a given sentence depends on the spatial configuration (produced by the action of putting) rather than on the verb.

Admittedly, languages do differ in how they encode spatial relations, which opens a huge and fascinating research field for comparative studies. Yet, this field falls outside of the scope of valency. While languages differ in the repertoire and exact meaning of markers of spatial relations, they are universally similar in that a locational argument of a verb allows a whole (sub)paradigm of markers available for marking spatial relations in the given language (Haspelmath/Hartmann 2015, p. 68).8 Consequently, verbs that take typical locational arguments, like the one in (3), should be excluded from our data. It is not the variability of marking as such that is problematic (cf. the discussion of data from Tab. 2 below), but the fact that this variability follows from the general rules of a given language and not from the use of a particular verb as a valency carrier.

To sum up, there are at least three large groups of verbs which are of little value for our research agenda and should be excluded a priori from the verbal meanings selected for the data.9 These are plain intransitives and plain transitives (i.e., verbs that only have arguments whose marking is predictable from the language’s alignment type), as well as verbs with locational arguments (i.e., those which have arguments whose marking is variable in the same way as that of locational adjuncts). Note that exclusion of plain transitives does not mean exclusion of all nominative and accusative markers. These are found with numerous verbs that still have other arguments. The latter class of verbs is what this paper and my whole project focus on.

←19 | 20→2.3 The Essentials of Comparing Valency

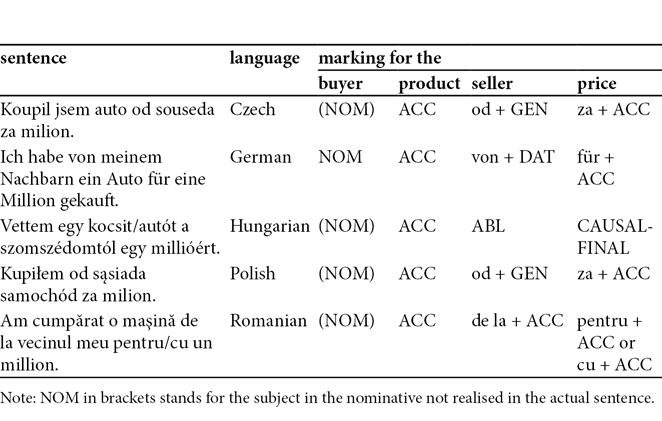

If we were to compare valency in, say, Polish and English, the obvious counterpart for the Polish sentence in (1) would be the translation with to buy provided as a gloss in the example. The comparison must at least start with semantic equivalence. As we have said, semantics permeates valency frames and makes not only verbs, but also the valency positions associated with them directly comparable. Tab. 2 compares (1) and its equivalents in all the analysed languages.

Tab. 2: Realisations of sentence 2 from the input for data collection

Note: NOM in brackets stands for the subject in the nominative not realised in the actual sentence.

Tab. 2 can be related to some of the issues raised above. For example, the pervasive nominative-accusative alignment is reflected in the first two columns. We can also clearly see the evident closeness of Czech and Polish—nearly all the words are recognizable as similar. This even applies to the adpositions marking valency, which are identical in form. Note also the availability of two markers in Romanian in the last column. The respective argument does not have a fixed marker in this language. This particular variation is not predictable from a cross-linguistic perspective, which is very different from locational arguments, cf. the discussion of (3). For this reason, marker variation like pentru + ACC/cu + ACC with the Romanian a cumpăra ‘to buy’ is indeed interesting from our perspective, unlike the marking of locational arguments.

←20 | 21→Yet, the most important thing related to Tab. 2 is the mechanics of comparison. We put Czech od + GEN, German von + DAT, Hungarian ABL, etc. in one of the columns, because the respective phrases od souseda, von meinem Nachbarn, a szomszédomtól, etc. (all meaning ‘from (my) neighbour’) have identical roles in the valency frames constituted by the semantically equivalent verbs in the respective languages. In other words, these phrases have the same microrole associated with the verbs meaning ‘to buy’ and this is the exact foundation of the comparison.

Let us analyse the path of establishing equivalence of markers step by step. The sentences in Tab. 2 are semantically equivalent, the verbs are semantically equivalent, the respective sets of phrases have the same microroles and are semantically equivalent. Following upon this, we equate the cases and adpositions used as valency markers. An important caveat is that we only consider the markers in the relevant context. Whether the markers in question are equivalent elsewhere does not matter.

The same kind of comparison must be applied to other selected verbs, too. It is clear that the grammatical markers of valency in any language are much less numerous than valency carriers. Thus, as the comparison progresses, most of the markers are bound to resurface. What we are interested in is which microroles share marking. This is consistent with the approach advocated for comparative studies of valency in Hartmann/Haspelmath/Cysouw (2014) and used in Haspelmath/Hartmann (2015). Gaszewski (2012) somewhat intuitively employs a similar approach in the analysis.

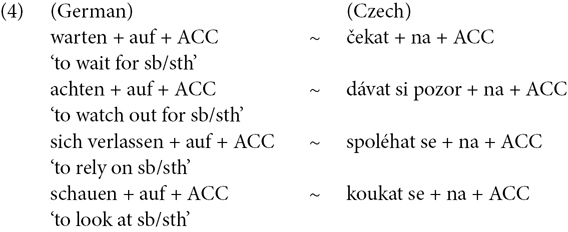

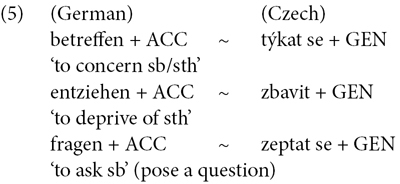

Thus, the unit of comparison is a single equivalence of markers for a particular microrole. It is clear that some equivalences will be found in the data more frequently than others. The recurrent equivalences of valency markers reflect the patterns shared by the compared languages. The following are two sets of German–Czech equivalences.

Let us stress again that the markers in (4–5) are equivalent in the given contexts, which is distinct from general semantic equivalence. The two kinds of equivalence may well coincide as they do in the case of (4), since German auf + ACC regularly corresponds to Czech na + ACC. In (5), by contrast, the two kinds of equivalence do not coincide.

Details

- Pages

- 360

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631806043

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631806050

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631806067

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631770115

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16313

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (December)

- Keywords

- Kontaktlinguistik Slavistik Hungarologie Typologie Grammatische Entlehnung Lexikalische Entlehnung Sprachlicher Transfer

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2020. 360 pp., 25 fig. b/w, 25 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG