Geopolitics of Central and Eastern Europe in the 21st Century

From the Buffer Zone to the Gateway Zone

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Dedication

- Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Central and Eastern Europe: in the eastern side of Europe or in the middle of Eurasia?

- 2.1 Between the West and the East

- 2.2 The multipolar world of the 21st century

- 2.3 The new Eurasia paradigm

- 3. Central and Eastern Europe: the historic region

- 3.1 Does a Central and Eastern European region even exist?

- 3.2 Cleavages in the Central and Eastern European region

- 3.2.1 Geographic cleavages

- 3.2.2 Civilizational cleavages

- 3.2.3 Geopolitical cleavages of the 21st century: the eastern border of the West

- 3.2.4 Economic cleavages

- 3.3 Going against cleavages: Visegrad cooperation

- 4. Buffer zone or gateway zone? Theoretical approaches and political-economic realities

- 4.1 The geopolitical structure of international relations

- 4.2 Buffer zone or gateway zone: theoretical approaches

- 4.3 From buffer zone to gateway zone: world economy opportunities and world politics realities

- 5. The 21st century’s forming multipolar world and the renaissance of orthodox geopolitics

- 5.1 The transforming world order and its system-level risks

- 5.2 Orthodox and critical geopolitics

- 5.3 The World-Island: the orthodox geopolitical interpretation of the largest supercontinent

- 5.4 American versus Russian Eurasian “grand chessboard” and its geopolitical consequences for Central and Eastern Europe

- 5.5 The concept of the East in traditional Hungarian geopolitical thought, from the early 20th century to the early 21st century

- 6. The world economy and geo-economic strategies of the 21st century

- 6.1 De-globalization and the 21st century

- 6.2 Hard power, soft power and economic power

- 6.3 The term “geo-economics” and its key elements

- 6.4 Economic great powers and economic empires

- 6.5 Business geopolitics: geo-economics and global risk management

- 7. The Larger West: NATO and the European Union

- 7.1 The USA and NATO in the Central and Eastern European region

- 7.2 The geopolitical consequences of further eastward European Union expansion

- 7.3 The “front line” between West and East in the 21st century: the geopolitical situation of the Western Balkans

- 7.4 From the East to the West? The geopolitical analysis of Ukraine

- 7.5 Russia’s most important Eastern European bridgehead: Belarus

- 7.6 Geopolitical periphery for the West and for the East: Moldova

- 8. The Eurasian supercontinent of the 21st century

- 8.1 Russia and Russian neo-Eurasian geopolitical orientation

- 8.2 Questions regarding Russia’s sea power

- 8.3 Russia’s special Central and Eastern European sphere of interest: the Western Balkans

- 8.4 The Chinese “One Belt One Road” Initiative and the new Eurasia paradigm

- 8.5 China and the Central and Eastern European countries: the “17+1” Initiative

- 9. The spatial organization of the new Central and Eastern European gateway zone

- 9.1 From historical buffer zone to economic gateway zone—new interpretation and delimitation opportunities

- 9.2 The EU’s trans-European transportation network (TEN-T) and the macro-regional strategy

- 9.2.1 The EU core network corridors through Central and Eastern Europe

- 9.2.2 The EU macro-regional strategy and the macro-regions of the Central and Eastern Europe

- 9.3 Transportation corridors and macro-regions affecting the Central and Eastern European region—outside the EU and/or not (yet) officially sanctioned by the EU

- 9.3.1 The Three Seas Initiative (TSI—3SI)

- 9.3.2 The new Amber Road railway corridor, the Via Carpathia highway, and the E40 waterway

- 9.3.3 The Carpathian Basin macro-region

- 9.3.4 The Black Sea macro-region

- 9.4 The Chinese gates of the Central and Eastern European region

- 9.4.1 China’s land gate: the Polish/Belarus Malaszevicze/Brest

- 9.4.2 China’s prospective second land gate: Záhony in Hungary

- 9.4.3 China’s sea gate: the Greek port of Piraeus

- 9.5 Macro-regions and gateway regions of the forming Central and Eastern European gateway zone

- 10. Summary

- Bibliography

- List of maps

- About the author

- Index

- Series Index

1. Introduction

The “godfather” of geopolitics, Sir Halford Mackinder, saw the region in the focus of this book, namely Central and Eastern Europe, as having exceptional strategic importance. After the end of the First World War, in his 1919 book “Democratic Ideals and Reality”3 he named the region the Middle Tier. Mackinder suggested that the countries between Germany and Soviet Russia form a joint dividing zone, or a “cordon sanitaire.” This belt between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea was seen by Mackinder as the western border of Eastern Europe and as such a strategic supplement to the “Heartland.” The Second World War and the Yalta conference that closed the war made it clear that a joint, neutral world politics role for the Central and Eastern European region would be impossible. After the 45-year socialist period the regime changes of 1989 and 1990 offered the countries of the region the chance to become members of the Euro-Atlantic sphere through the European Union and NATO.

The Cold War and the bipolar world order came to an end, but their general geopolitical mode of thought persists. This is clearly illustrated by the fact that the fundamental question for the former socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe remains: where are these states, in the West or in the East? Large portions of the populations of these countries sense a danger in strengthening ties with Russia, fearing the region will return to the Russian sphere of interests. But can we move beyond this traditional geopolitical point of view? A new multipolar world is currently forming, in the early 21st century, but we have yet to create a set of geopolitical and world politics concepts to match it.

Are prognoses regarding the European Union—predicting the strengthening of macro-regions within the EU—accurate? Will an economic and political sphere of power along a North-South axis in Central and Eastern Europe be established? Would this sphere have an independent role within the European Union? Can this region break free of its position of “imprisonment” between West and East? Will Polish Marshal Józef Pilsudski’s post-World War One settlement idea of an Intermarium region be established in the near future? Will countries between the Baltic Sea and the Adriatic Sea to the Black Sea establish closer cooperation in the interest of creating larger economic and political sovereignty? ←15 | 16→In light of their geopolitical situation, to what extent will they be haunted by the “ghosts of history,” regularly allowing great powers to decide their fate for them?

This book is an invitation to the reader—or all those who strive to understand geopolitical strategies of the early 21st century, who feel responsible for the future of Central and Eastern Europe, who, aware of the region’s history, understand that nothing is more important that liberty and political and economic sovereignty—to think together. We live in an age which is at once complicated, unstable, and in a security sense rather risky. But this emerging multi-polar world also provides new opportunities, and Central and Eastern Europe, instead of always floating adrift in world political affairs, almost permanently serving as a buffer zone between great powers, can became a gateway zone between Europe and Asia, or between the Atlantic sphere’s great powers and the emerging states of Asia. There is no question that the most important building block for such is strengthening the economic development, economic independence and world market competitiveness of Central and Eastern Europe. The author has written this book through the lens of this positive view of the future, not forgetting in the meantime that buffer state or buffer zone existence is as much a matter of domestic politics as foreign affairs. The most important foundation of the gateway region or gateway zone role is social consensus, thinking cooperatively and a willingness to pull together in one direction.

According to Mackinder’s writing—these being some of the most-quoted sentences in geopolitical science—rule of Eastern Europe is the basis of world rule. The 21st century offers Central and Eastern Europe an opportunity to take a new position on the geopolitical “chessboard.” This is a strategic geopolitical situation which could possibly lead world political and economic leaders in 20– 25 years to say the following about Central and Eastern Europe, the most important element of success in world politics and world economics in the 21st century is cooperation with the countries of the Central and Eastern European region.4

Budapest, October 23, 2020.

Agnes Bernek

2. Central and Eastern Europe: in the eastern side of Europe or in the middle of Eurasia?

2.1 Between the West and the East

When examining the geopolitical roles of Central and Eastern Europe, regularly the main question is, where is this region, in the West or in the East? What is more important, which is more significant: being a border zone of the Atlantic sphere of power or being the western bridgehead of the now-forming Eurasian sphere of power?

The positing of such “West or East” questions is not appropriate for the world of the 21st century but is more a product of the traditional North-South and East-West divisions of the world in the second half of the 20th century. In the 1980s, under the leadership of former West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, the so-called Brandt report was written on divisions in world politics and world economics, which were presented according to North and South geographic orientations. The so-called Brandt line divided the world along the latitude of 30° N into a developed northern region and developing southern countries. But in the time of the Cold War the developed north itself was divided in two along political system divisions, with the capitalist western world and the socialist (the Soviet Union and the socialist countries of Europe) eastern bloc standing in opposition to one another.

To this day this West-East division forms the foundation of our thinking on international geopolitical space, despite the fact that since the time of the regime changes of the 1990s the world has become unipolar, with the logic of the international divisions of the Cold War having lost its meaning. What is more, given the rising and growing markets among the countries of the earlier under-developed south, the North-South division has also lost its relevance. This is so much so that in world politics and world economics discourse in the 21st century the term ‘developing country’ is no longer in use. It is important to stress that the basis of this traditional geopolitical interpretation of geographical cardinal directions is that appears evident to us that the European continent is the central region of the planet. As such, we have always used maps of the world in which Europe is in the center. As a result, the foundation of the North-South, but especially the West-East geopolitical point of view is that we traditionally study the geopolitical space of the 21st century from an exclusively European stance. At the beginning of the 21st century can the countries of Central and Eastern ←17 | 18→Europe change their traditional geopolitical world views? Most importantly, can they move beyond the ingrained stereotype in their thinking, according to which “the West is always looked up to, while the East is always looked down upon?”

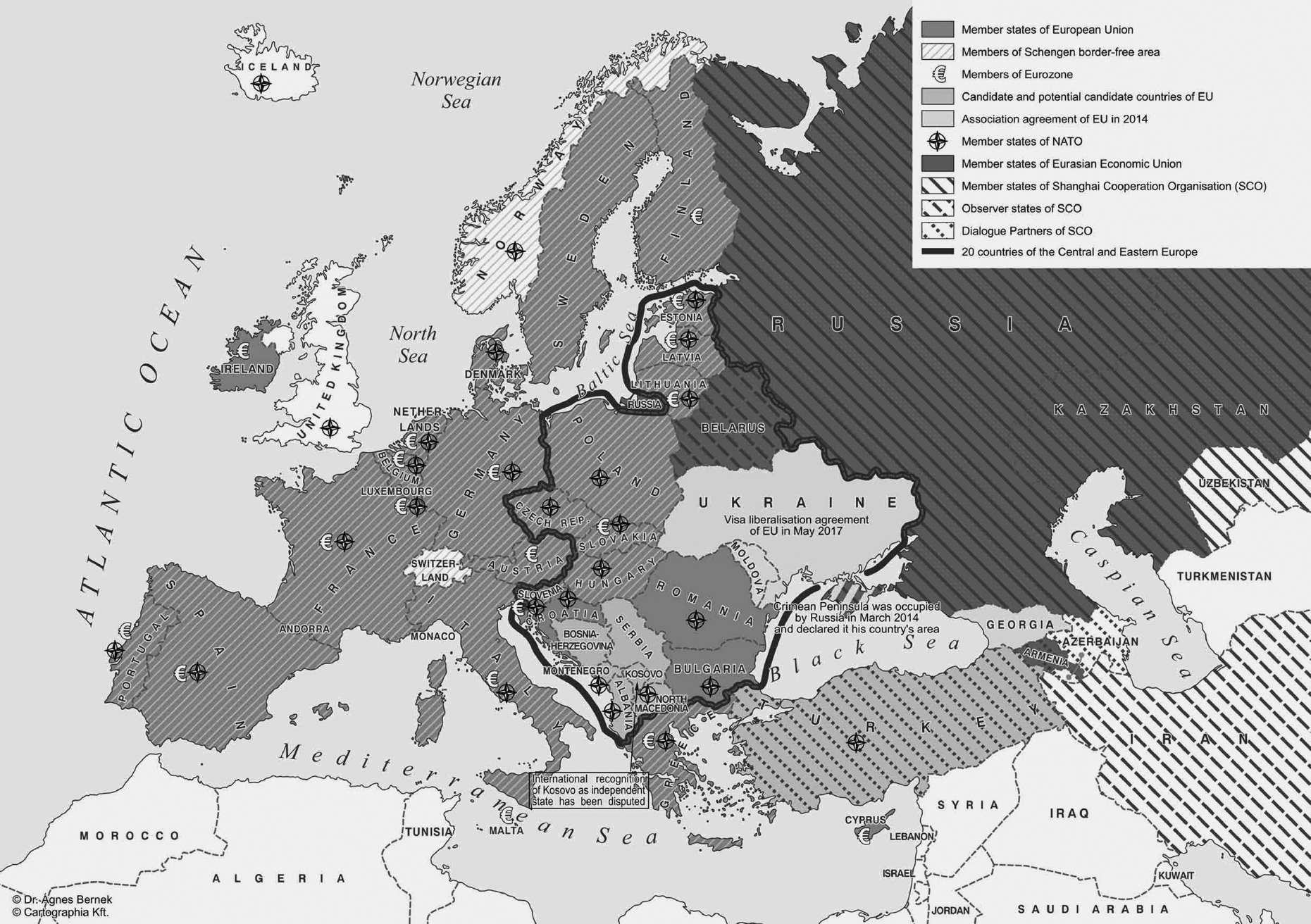

In the case of the Central and Eastern European region it is difficult to escape from the “cage” of Cold War-era West-East thinking. Case in point: following the Russian annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in March of 2014, through antagonism between the USA and Russia, the region of the Central and Eastern Europe increasingly became a buffer zone; a role it had historically played several times. The multipolar world taking shape today offers new geopolitical opportunities. We must find a new vision to replace the “fossilized” West-East geopolitical mode of thought, and as such, relatively speaking, the geopolitical situation of the Central and Eastern European region can in the near future be interpreted in an entirely new way. The Central and Eastern European region, as a buffer zone between the Euro-Atlantic sphere and the Eurasian sphere (along with its current situation) is shown in Map 1.

2.2 The multipolar world of the 21st century

In 2020, it is accepted as fact that after the unipolar world based on the hegemonic role of the USA and the Atlantic sphere in world politics and the world economy there is now forming a new multipolar world. The world role the USA filled as “first among equals” has now come to an end, and in geopolitical terms we can state that the spatial diffusion of power has begun. But what will this multipolar world be like? Given that the regulatory system of the now emerging multipolar world has not at all been developed, the current period of complete uncertainty can be traced back to so-called system-level geopolitical risks. With China now boasting the world’s second-largest national economy, the Anglo-American world economy regulatory order is being challenged by other political and economic models and economic modes. There is a so-called non-Anglo-American world forming (alongside the Anglo-American, for the time being). As such the traditionally understood “the West’s” dominance is becoming increasingly questionable.

The 21st century’s geopolitical “grand chessboard” is fundamentally changing, and with the European Union and European countries in crisis since 2008, the world’s central region is increasingly that of the Pacific Ocean sphere. The grand strategies of the 21st century will be examined exclusively based on the efforts of three great powers, namely the USA, Russia and China. The world is turning, and all signs point to a 21st century that is not the European century. And given the above, the Europe-centric world view will change, if only slowly, and interpretation of the divisions in the international order viewed along the traditional North-South and East-West fault lines will transform. Or in cartography terms, the reference point is changing, and the world can be understood not only from the view in Brussels and Washington, but also from that in Beijing and Moscow. This is all to say that we must develop a fundamentally new geopolitical spatial orientation.

←18 | 19→

However, we now witness a renaissance of orthodox (traditional) geopolitical approaches. The unquestionably most-quoted author in current geopolitics is Halford J. Mackinder (1861–1947), a British geographer of Scottish origin. The two most important terms in geopolitics – “Heartland” and “World-Island” – have their origins in Mackinder’s writing. Regarding political analysis of Europe and Asia, Mackinder sought to answer the question of what correlations stood behind geographic and historical processes and key events. Mackinder’s “World-Island” concept meant Eurasia (and Africa), which indicates not only Europe and Asia as a single continent in the geographic sense (and hence the planet’s largest continuous land mass), but also stresses that the peoples and states of Europe and Asia form the center of world power (Mackinder, 1919).

The term Eurasia is one of the most debated concepts of our time. In the western half of Europe the term’s very existence is denied and is often identified with Russia or the resurgence of the former Soviet Union. Hungary also employs stereotypes characteristic of the Cold War in its thinking, with Europe synonymous with the so-called West and Eurasia identified with the East. The commonly held political notion that Hungary must choose between Europe and Eurasia is fundamentally flawed both geographically and geopolitically.

Despite so many changes, the basic question of geopolitics remains unchanged. Namely, will Mackinder’s “World-Island” come to exist at all as a factual territorial unit? Will we, in the near future, study world political relations in terms of the “World-Island” vis-à-vis the Americas? Will the USA’s Cold War-era policy of containment continue, and if yes, then what methods will the country employ to obstruct Europe and Asia from forming strong economic and political relations? Will increasing economic cooperation between Russia and China lead to the development of a new Eurasian supercontinent? What kind of new multi-polar world will this bring about? And what will be the position of the countries of the Central and Eastern European region in the currently forming Eurasian supercontinent?

←20 | 21→2.3 The new Eurasia paradigm5

One of the essential concepts in this book is the so-called new Eurasia paradigm. The most important components of the concept are the following:

In the 2000s—from the beginning of Putin’s presidency, and from the consolidation and growth period of the Russian economy and political constellation—the Eurasia concept was associated exclusively with Russian geopolitical aspirations (as a post-Soviet term). In the West, Russian geopolitical strategy was seen as carrying the danger of the “resurgence” of the Soviet Union (this view persists). It is no coincidence that the term was completely rejected in the countries of the Euro-Atlantic sphere, where the idea of the building of a Russian-led alliance and sphere between Europe and Asia was seen as impossible.

In the 2000s—from the beginning of Putin’s presidency, and from the consolidation and growth period of the Russian economy and political constellation—the Eurasia concept was associated exclusively with Russian geopolitical aspirations (as a post-Soviet term). In the West, Russian geopolitical strategy was seen as carrying the danger of the “resurgence” of the Soviet Union (this view persists). It is no coincidence that the term was completely rejected in the countries of the Euro-Atlantic sphere, where the idea of the building of a Russian-led alliance and sphere between Europe and Asia was seen as impossible.

Details

- Pages

- 242

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631845684

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631845875

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631845882

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631819159

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18155

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (March)

- Keywords

- multipolar world New Eurasia paradigm World-Island Greater Central Europe Baltic-Adriatic axis gateway region

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2021. 242 pp., 51 fig. b/w, 5 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG