Racial Reconciliation

Black Masculinity, Societal Indifference, and Church Socialization

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

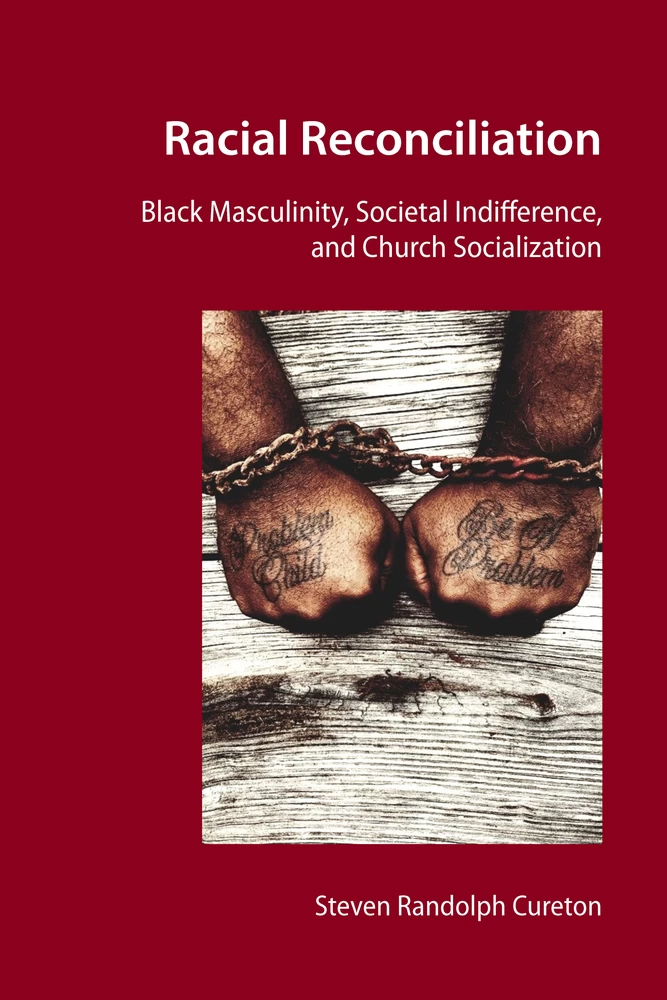

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: America Be Kind to Us Outside of Consciousness of Kind

- 1. Malcolm X Has Spoken: Racial Reconciliation over Racial Agitation

- 2. Wickedly Black: Making Monsters out of Black Males

- 3. Racial Equity and Criminal Justice

- 4. Black Churchin’ and Black Flight: Something Wicked This Way Comes and It’s Black Gangsterism

- 5. Chance or Testimony: Am I Ever Your Equal?

- 6. A Time to Listen: A Conversation about Race, the Church, and Where Do We Go from Here?

- 7. The Common Thread in Post-Racialism

- References

- Index

Meet Me Lord, So That I May Reconcile

I respect Bessie, my mother. In fact, my life has been a testament of trying to honor her, so the narrative below speaks to a depth of turmoil that only spiritual reconciliation could effectively counter. Additionally, I miss my brother Jeff, dearly. His passing in March of 2019 represented an emotional jolt. It is as if his passing severed a piece of my heart. The deaths of my mother and brother have in common that I didn’t feel I could stand up to the slightest breeze. It might as well have been a windstorm effecting an unstable walk everywhere I went. The irony is that it seems poetic justice that Jeff, my mother’s favorite, would be the first to follow her, departing this lifetime. Perhaps these two have transitioned to a place where they are not capable of looking back on this world in a way that matters, so maybe it’s time to reconcile in a manner that restores an intangible good. The intangible good being that there is something special about the relationship between mother and son and there is truth to the fact that brothers are born for adversity.

I was born September 14, 1968. I have two older brothers, Tony and Jeffrey, and two younger sisters, Paula and Sonnettle. I guess I am what you call a double middle-child having two older brothers and ←ix | x→two younger sisters. There was a time I was so amazingly distanced from my mother that I thought there was absolutely no way I could be her son; therefore, I changed the spelling of my name from Stephen to Steven. At the age of 14, I ran away from home and would eventually become a ward of the court and was temporarily awarded to Ms. Mary Rogers. Aunt Mary was a Godsend because it was not until she assumed custody that I felt I was a favorite boy, having favor and worthy of God’s grace over my life. Before legal guardianship was transferred to Aunt Mary, there was a custody hearing.

My mother whose alias was Bessie, McCray Walters had been locked up in a prison in Virginia and had very little contact with me. When she was released, she immediately wanted all of her kids back. I was terrified of this woman because she kept me out of school for an entire year and had threatened to kill me, holding a knife to my throat. What prompted my mother to put a knife to my throat? Believe it or not, she was cooking some meal in one big pot; we called it “prison goulash.” The poor version of “prison goulash” was anything in the cabinet she could find to put in one pot. I was probably complaining about the food and asking, “Where is the meat?” No, that didn’t move her. My follow-up was, “Momma, can I go to school?” It was at that moment I could feel the blade of a warm knife on my throat. Mother said to me, “You getting on my nerves, crybaby.” She was correct; tears were streaming down my face. I never asked about school again. More than anything was the constant rejection. Just the thought of knowing and struggling to win her affection to what seemed to be futile attempts continues to bother me.

My mother was in and out of jail for a good part of my life. I did not want to have to live with her. I was starting high school in Goldsboro, North Carolina and was adjusting well. I recall my mother being present at the court hearing, pleading to the judge to return custody of me over to her. The judge asked me with whom I felt safe. I was an awkwardly nervous 14 year old, and standing up with a level of fear, embarrassment, and shame, I murmured, “Aunt Mary, Mary Rogers, Sir.” The judge continued, “Why Mary Rogers?” I responded that I liked going to school, and mother would not allow me to go. I do not know what grade I am really supposed to be in; I was just placed in ←x | xi→the ninth grade. I hate the police as they are constantly arresting my mother; I came to Danville Virginia in the back of a U-Haul truck sleeping on garbage bags full of clothes, and my mother can’t tell you who my daddy is or my birthday. The judge asked the social worker, Doris Avery, what her recommendation was.

The social worker read from a report, “Stephen has adjusted very well to living with Ms. Rogers. The legal custody of Stephen should remain with Ms. Rogers and reviewed again in October of 1986.” The judge turns to my mother and asked, “What is Stephen’s birthdate?” My mother looks over at me asking how I could do this to her. She then responded that she had been locked up and she was trying to get on her feet; she needed her children back to get assistance and that she does not know my birthday. With that, the judge allowed me to continue staying with Mary Rogers, effectively closing case #83-J-43.

I finished all of high school in the custody of Mary Rogers and never had to look back at custody issues or my mother. I went through four years of college at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, graduating in 1990, and then went off to Washington State University, graduating with a Ph.D. in 1997; therefore, I went 15 years without seeing my mother. I saw her for the first time after my daughter Nia-Faye was born in 1998. I thought to myself, “What a frail woman! She does not look much like a monster anymore.” I remember she wanted to hold my child. I reluctantly allowed her to but watched her like a hawk thinking, “You will never bring harm to this one.”

My forgiveness was unfortunately far too late. Our attempts at reconciliation never experienced full maturity because I was holding on to the feeling that a son’s first love, his mother, was not reciprocated. More than that, there was a level of what appeared to be intentional abandonment, outright rejection, and a clear hierarchy of favorite children, where I was the least favorite. This is not to take anything away from my sister Paula because mother went after her in unbearable ways but that is Paula’s story to tell.

One last story with respect to my mother: One of her favorite meals was curry chicken. She would order that meal all the time. Growing up poor, we thought we would get some of those scraps as she never ate it all. Without fail, she would call Jeffrey in for the first round of leftovers. ←xi | xii→I was last and I could only get the leftover curry juice. I sipped it, however, thinking I was lucky. Fast forward to 2009–2010, my mother would come to stay with me for a couple of weeks during the summers, which is a testament to some level of forgiveness. Often she would order curry chicken. I would buy it, prepare her plate, take it upstairs, and ask her, “Could I get a piece of her curry chicken? Mother would hand me her plate saying, “Take a piece, Stevie.” We remained at odds – her feeling she deserved to be treated like a number one mom, and me thinking otherwise.

Time went on and there were several attempts to at least get to know my mother; during those times, I was impatiently mean. My sister, Sonnettle, would always say, “You need to get to know your mother.” I tried but all I ever got out of her was, “I am still your mother and could you buy me something.” I bought her stuff but I was blessed and was lucky that Sonnettle was actually her caregiver. My favorite purchase for my mother was a cross. I have that cross now. My mother passed away on November 15, 2011; the cause of death was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary embolism with a significant condition of diabetes mellitus. I eulogized my mother at the funeral services. As I stood over the casket, all I could remember saying is that I wanted people to leave my mother alone, “She is at peace.” I also remember saying, “Mother, don’t look back, don’t haunt us, we are good, all of us are good.” My mother loved me the best way she could, I guess. She was a troubled woman with five kids. She more than likely had intangible psychological deficits that prevented functional love. She did the best she could with what she had.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 138

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433175848

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433175855

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433175862

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433175879

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16728

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (July)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. X, 152 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG