Misunderstood, Misinterpreted and Mismanaged

Voices of Students marginalised in a Secondary School

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface: Different Approaches to Reading This Book

- Chapter 1 Motivation: Educational Inequality Is Still on the Rise Accompanied by Increased Instances of Marginalisation

- Chapter 2 The Study and Methodology

- Chapter 3 Transition: Going from Big Fish to Little Fish

- Chapter 4 Sets, Selections and Separations

- Chapter 5 The Effective Classroom: Likes and Dislikes

- Chapter 6 Barriers to Learning and How They Are Occasionally Overcome

- Chapter 7 Towards Tackling Marginalisation

- Appendix A: Table 2: Student Data

- Bibliography

- Index

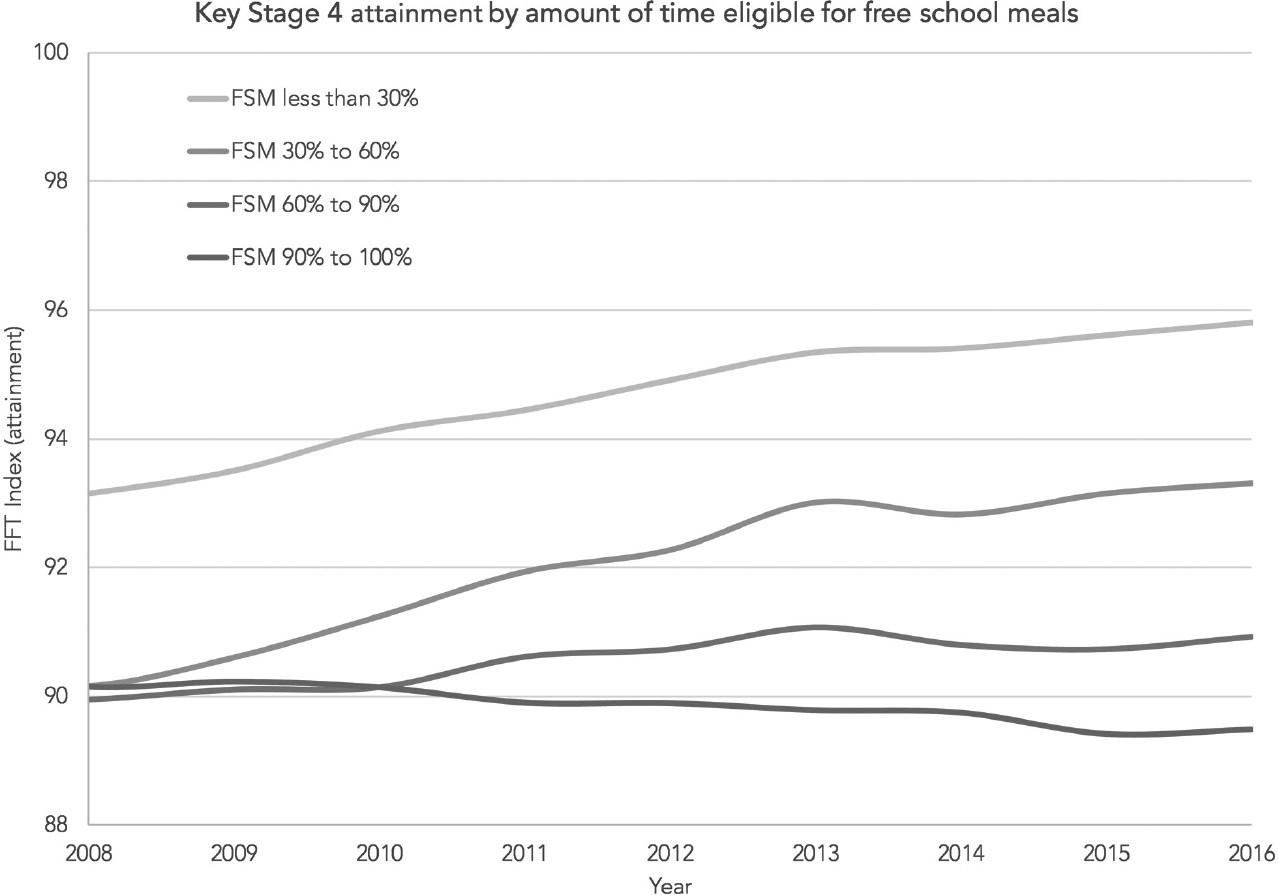

Figure 1: For the ‘Long-Term Disadvantaged’ the Attainment Gap at KS4 Is Widening

Figure 4: Deeply Embedded Diagramming A

Figure 5: Deeply Embedded Diagramming B

Figure 6: Deeply Embedded Diagramming C

Figure 7: Deeply Embedded Diagramming D

Figure 8: Deeply Embedded Diagramming E

Figure 9: Deeply Embedded Diagramming F

Figure 10: Deeply Embedded Diagramming G

Figure 11: Deeply Embedded Diagramming H

Preface: Different Approaches to Reading This Book

The inspiration for the research behind this book comes directly from the classroom, with the seed evolving from musings and reflections on the day-to-day, commonplace yet extraordinary educational experiences of some of the students I had the pleasure to meet, to teach and come to know along the way. This book is underpinned by their stories.

As a teacher within the mainstream secondary school sector for fifteen years, working over a period of considerable change and volatility in schools in challenging circumstances, I oscillated between being exasperated, inspired, encouraged and incensed by the lived experiences of schooling of many of my students. These students whose experience of schooling I found so emotive and thought-provoking, were invariably those who felt side-lined, marginalised, overlooked, neglected or even rejected, in some manner or at some moment along their educational journey. For me, their strength, their long-suffering patience and their frustrations prompted many questions. How did this marginalisation come about and how might it be otherwise? What can be done to pre-empt vulnerable, socially disadvantaged students from becoming marginalised and disengaged? What are the implications for best practice within schools and the ramifications for system structures? The seed was sown, my research began and this book resulted. It seeks to give a voice to these students as a way of understanding the triggers, causes, effects and consequences of disengagement from mainstream education. The power of the book is having these marginalised students voices at its core. The strengths undoubtedly lie in reflecting upon, analysing and contextualising the stories, thoughts and opinions of these rarely listened to, marginalised students. Any weaknesses are all mine.

This book should be of interest not only to the archetypal audience for a research-informed book – namely researchers, academics and those policy makers with a research-informed leaning – but also crucially to teachers at all levels as well as others with an interest in educational inequalities and wider issues of social justice. Anyone with an interest in schooling, in schooling for all, in educational equality – perhaps in particular in understanding inequality of experience – or of course more specifically in marginalised students, their learning, their experiences, their thoughts and opinions, can gain insight from reading this book and hearing the voices within.

In reflecting on my own time in schools and my many fabulous colleagues, I can see different things for different colleagues within this work – the beginner teacher contemplating the diversity of their students; the experienced classroom teacher delving deeper into engagement for every student; the teaching assistant, mentor or special needs teacher always keen to develop a greater understanding and empathy for their students; the middle or senior leader looking for wider departmental or school strategy ideas to embed greater equality. That is not to say that a novice teacher may not be drawn to theory, to strategy or to policy implications. Each reader will decide for themselves whether or not to read every aspect with equal diligence or to skim over elements with which they are already familiar or which are of less bearing at that moment.

I wish to facilitate such a range of readings. Indeed I believe I would have approached reading this book differently myself – at differing points within my own professional history. With this in mind, I have structured this book so as to enable several different approaches to reading. I have broken it up so that the reader can choose their own route through, returning – or not – to sections skimmed over or omitted at a later date should the mood strike them or interests, priorities or circumstances change.

The introduction draws from a range of other educational research to set the scene; touching on the current state of educational inequality in secondary schooling in England and research outlining thinking on how it is that such educational inequality may come about or be exacerbated. Readers already familiar with such ideas or simply those eager to hear what this research has to add may choose to set this aside initially.

The methods section justifies the robust and rigorous nature of the research presented here. As such it is theoretical and academic in nature, touching on methodology as well as justifying and illustrating the particular analytic approach taken. Some readers may well choose to set-aside delving into the details of the research methods, to move directly to where the student voices come through.

In terms of the heart of the work, the findings indicate that there is a range of factors, which students perceive as fuelling their marginalisation within the secondary education system. Some of these factors are associated with system structures, issues of transition, settings and separations onto different pathways. Others stem from their experience in the classroom or relate to labelling and issues of identity. The results chapters are sequenced so as to begin with the wider systemic factors and then to progressively zoom in, firstly to the scale of the classroom and then to consider more individual level factors. Findings are presented under four umbrella categories, each of which forms a result chapter here: transition; sets, selections and separations; the effective classroom; and barriers to learning. Within each of these chapters the voices of the marginalised students are laid bare to support the case being presented. Findings sub-sections are interwoven with sub-sections where the student experiences and stories are set against current research, theory and policy. These are clearly entitled ‘situating the accounts’ or ‘situating the findings’. The reason for this separating out of accounts and findings from attempts to situate them, is twofold: firstly, to keep the students’ voices to the fore and secondly to facilitate different reading routes through the book. Readers may choose to omit or only skim particular sub-sections where the findings are situated within wider thinking. This may be because they feel sufficiently well versed in the current academic thinking. Alternatively, it may be as their motivation lies substantially in practice as opposed to theory. Nevertheless, the material is there to return to should contextualisation be sought, a desire for pointers to other research in a particular area of interest arise, or a taster of a more academic pathway appeal.

The final chapter pulls together and summarises the preceding findings and contemplates ways forward to address marginalisation, disengagement and aspects of educational inequalities. There are point-by-point suggestions for classroom and school practice, which can be implemented at different levels, as well as more holistic, far-reaching options to address educational marginalisation. Indeed, to really take the students’ experience seriously, I argue, entails moving beyond reforms and adaptations, to think about education differently. What is needed to tackle and eradicate this marginalisation, is a radically comprehensive education system structure, with ‘the social’ at its heart, where critical pedagogy is realised. Whilst the conclusions are likely to be of general interest to the full range of readers, the practitioner and the pragmatist may be more likely to be drawn to the more immediate, smaller-scale actions. Indeed, there is an explicit table highlighting possible points of interest, aimed at particular practitioners. The theorist, the researcher and the dreamer may have more patience for the wider possibilities for change. Many of us of course are both pragmatists and dreamers.

CHAPTER 1

Motivation: Educational Inequality Is Still on the Rise Accompanied by Increased Instances of Marginalisation

This research is an ethnographic study of marginalised students based in one secondary school in England, Welford High.1 It has at its core a concern for the experiences and perspectives of those students who pass through the on-site withdrawal-unit that operates in the school. Some flourish there and reintegrate with mainstream full-time timetables, others engage successfully but do not return to all lessons and a few end up subject to further interventions, alternative provision or exclusion from school. Their experiences, opinions and stories are sought to shed light on what it is to be a marginalised student within the secondary education system.

Before I outline the study, I will address why it is that I feel this research is relevant, timely and necessary. In order to do this, I will review some pertinent aspects of the state of play in the education system in England as it stands, albeit in its eternal state of flux, and draw on some relevant literature to consolidate my motivation: namely that educational inequality is on the rise and this is accompanied by increased instances of marginalisation.2

Firstly, in what sense is it that I am asserting that educational inequality is on the rise? There are many meanings of inequality in education – inequality of opportunity, inequality of experience, inequality of outcome for instance – some of which lend themselves readily to being quantified and each of which can be viewed across different phases of education and ←1 | 2→compared and contrasted for different subgroups of students. While government ministers regularly argue that their evidence shows that overall levels of school performance are rising and the gaps in attainment between students of different social backgrounds are closing, albeit very slowly, this is not the case for those students referred to as the ‘long-term disadvantaged’; the attainment gap at Key-Stage 4 between these students and others is actually widening, and their levels of performance are in decline.

For pupils who were FSM-eligible on almost every occasion the school census is taken (90% or more of the time), their attainment, relative to the national average, has actually been falling. This is the group that we’re going to refer to as the long-term disadvantaged. (Education Datalab, 2017)

It is the plight of long-term disadvantaged students with which I am concerned here and more specifically the experience of those students who spend parts of their educational careers on the margins of mainstream ←2 | 3→schooling. My argument here is that previous and ongoing educational reforms produce arrangements for schooling which contribute to or create marginalisation for some students and consequently produce and indeed lead to an increase in inequality in terms of the performance and school outcomes of these students compared with their mainstream peers.

Significantly Increasing Competition in the School Market Place

With the recent explosion in the number of converter academies, the already fragmented secondary school system is fracturing still further. The education market place is being made more complex and fuzzy by the proliferation of schools with greater autonomy and of greater diversity and in some parts of the country competition between providers is rife.

For decades now the secondary school sector has had a variety of schools, not only those over-seen by the Local Education Authority (LEA), the Community and Voluntary-Aided Schools, but also the Foundation, Specialist and Grant-Maintained Schools. There are Local Authorities where selection by ability remains in the form of Grammar schools and, as ever there is the small but persistent independent sector. More recently the Sponsored Academies were established under Labour and provided a springboard for the Coalition’s dramatic introduction of Converter Academies, as well as Free Schools, University Technical Colleges and Studio Schools.

It is quite simply the sheer scale of these most recent changes that make them significant here.3 My point is that this disarticulation and diversity makes the system increasingly difficult to navigate for parents and students, and creates more points of differentiation and potential inequity. There is ←3 | 4→a plethora of research, which indicates that branching points, partitions and choice contribute to inequalities (Kulik and Kulik, 1982, 1992; Slavin, 1990; Ball, 1993, 2003b, 2003a; Tomlinson, 1997; Gillborn and Youdell, 1999; Gibbons and Telhaj, 2006; Green, Preston and Janmaat, 2006; Allen, 2007; Burgess and Briggs, 2010; Wilson, 2011; Orfield and Frankenberg, 2013). It is likely that this recent expansion of diversity and autonomy will also have dramatic consequences in these terms. If inequalities are to be minimised, interventions should be in place to assist those students most likely to be disadvantaged and marginalised by such changes. It is in this context that, I suggest, there is an urgent need to understand and address the issue of marginalisation.

Evidence in support of the argument that rising inequality results from increasing choice and competition between schools is plentiful. I will briefly draw on some diverse sources to substantiate the argument that increasing the diversity of provision, just as the expansion of the academies programme is doing at this very moment, invariably seems to lead to greater inequality and more instances of marginalisation.

Market Policies Leaving an Opening for an Increase in Inequalities

In the broadest sense, Ball reminds us that market policies, while they may not directly decrease equality, certainly do not prioritise such concerns.

The values and incentives of market policies being pursued and celebrated by the states of almost all western societies give legitimation and impetus to certain actions and commitments – enterprise, competition, excellence – and inhibit and de-legitimise others – social justice, equity, tolerance. The need to give consideration to the fate of others has been lessened in all this. (Ball, 2003b, p. 26)

Details

- Pages

- XX, 330

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789975628

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789975635

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789975642

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781789975611

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15985

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (March)

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. XX, 330 pp., 13 fig. b/w, 2 tables.