Parody and Pedagogy in the Age of Neoliberalism

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

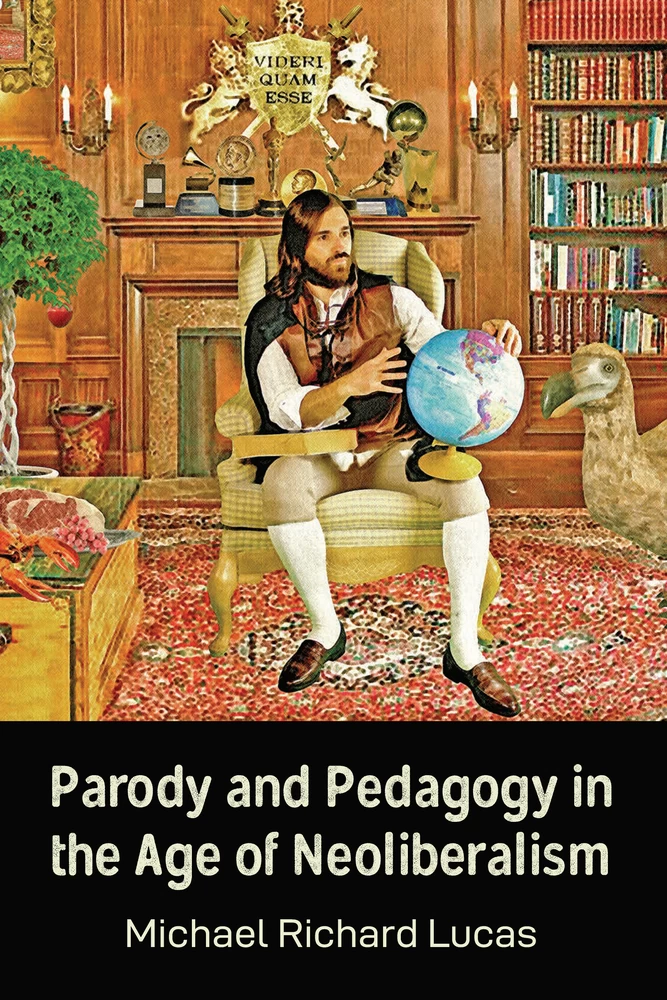

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1. Informal Introductions

- Somewhat Formal Introductions

- A Very Serious and Very Formal Introduction

- The Parodic Gorgias

- A Pedagogy for Our Multipersonned Self

- The Serious Bias and the History of Rhetoric and Humor

- Neoliberalism and Appreciation

- My Main Argument #1

- My Main Argument #2

- Chapter Outlines

- Chapter 2. Defining Humorous Parody

- A Serious Bias Separating Humor and Parody

- Differentiating Parody

- Further Differentiations from Satire and Irony

- Differentiating Parody from Other Comedic Forms

- Parody as a Legitimate Art Form and Discourse

- Defining Paraumhordyor: Targeting Conventions

- Defining Paraumhordyor: Acting as a Critical Rhetoric

- Defining Paraumhordyor: Acting as a Form of Agonistic Debate

- How Paraumhordyor Accounts for Our Multipersonned/Kairotic Selves

- Chapter 3. Narrating Our-Selves

- A Narrated Overview of Narration

- Narrating the Selves

- Mass Media Narratives

- Problematic Mass Narratives: Foucault and the Productive Dimensions of Power

- The Panopticon and Self-Surveillance

- Homo Economicus in Visual Narration

- Helpful Practices of Self-Narration

- Chapter 4. Parody Functioning as a Mass Narrative Therapy in Contemporary Visual Entertainment

- Paraumhordyor as a Mass Narrative Therapy

- Examples of Paraumhordyoric Mass Visual Narratives

- Chapter 5. Creative Atmospheres of Play Enabled by Paraumhordyor

- Roadblocks to Creativity: Neoliberalism

- The Myth of the Creative Genius

- Moving Beyond Argumentation and Critique Toward an Impetus to Create

- Play-aumhordyor

- Humor Provides a Creative Atmosphere

- A Kairotic User Experience

- Playing with Time

- An Individual’s History of Creativity as Classroom Activity and/or Narrative Therapy

- Playing with Our Multipersonned Self

- What Can Prevent This

- Calling Other Worlds

- Chapter 6. Parody as a Critical Public/Classroom Pedagogy

- The Importance of Humor and Play in the Classroom

- Beneficial for Critique

- Beneficial for Creating

- DIY/Amateur Digital Video Creation

- Student Examples

- The Non-Digital Provisional Prescriptions: Absurd-ify and Caricature

- Conclusion?

- Index

This book is very serious and very philosophical. This is not a funny book. My motive for writing this book is to sell copies and further my professional career. Tell everyone you know about how much you enjoyed this book, how much it helped you, how much it made you laugh, and—most importantly—tell them how serious it was.

There are no mistakes in this balk, just opportunities for you to benefit from my stupidity. If you have any criticisms of this book, you should thank me: I have provided you with an opportunity to be serious and look very smart; e.g., you can write a vitriolic review of this book online, serve up a caustic comment at your next dinner party, etc. This would not have been possible without the work I have done here. Even if you hate it, tell your friends and enemies to read it so that you can talk about how much you hate it. The worst outcome is that you don’t talk about it. That would certainly hurt book sales. However, on second thought, I meant to make the mistakes I’m milking. Perhaps a mistake is the only authentic thing you can make? Without mistakes perhaps all we ever do is make something that conforms to enough conventions to encourage others to move the discourse forward in new ways; i.e., ← 1 | 2 →describe new/not yet recognizable language and never before seen actors and settings while waiting for others to figure out that we are merely describing something (in very sophisticated language) that has always been occurring and will continue to occur long after we are gone.

If the only constant in scholarship is that newer and better scholarship will replace older and outdated scholarship, a scholar is more justified in providing more wrong answers than right ones. If the right answers of today are merely meant to be replaced, and if they only serve as stumbling blocks and distractions (i.e., ideals that prevent young scholars from generating new ideas), you would be better off providing others with wrong answers. Young scholars would not sit distractedly stargazing at these only temporarily right answers that are inevitably wrong, and if you have provided people with wrong answers during your lifetime, you are more likely to be right during another lifetime. Therefore, you should only provide people with wrong answers. If my right answer turns out to be wrong, I will have succeeded in providing you with the wrong answer. Which is the right answer. How do we know if our answer is right or wrong? How do we know that which can’t be known? The only way to answer a question that has no answer is not to ask the question in the first place.

When I began conducting researching for what would eventually become this book, there was a surge in the scholarship on—and creation of—parodic narratives within the public sphere. As many scholars have already noted, any parodic surge suggests a growing mistrust of the serious rhetorical strategies in the public sphere. My research began toward the end of a high-water mark on conducting academic scholarship on The Daily Show and The Colbert Report (elaborated on in Chapter Four). Circa 2004–2011, such scholarship appeared to open up discourse and publications on parody, satire, and irony. This most recent surge (there have been many throughout history) can be attributed to innumerable factors occurring within the public sphere: the increased popularity of these comedic fake news2 programs, other forms of parodic and satirical infotainment such as The Onion and other similar social media outlets, broadening appeal and accessibility of culture jamming as seen with The Yes Men and documentaries like those of Michael Moore, as well as amateur ← 2 | 3 → YouTube parodies, remixes, mashups, memes, etc. This parodic atmosphere was further fueled by the sentiments of a younger generation fed up with corporate pandering and incompetent politics.

In this atmosphere it now appeared permissible for academics to publish scholarship on comedic fake news programs, if they fit enough serious criteria. For example, these shows were seen to enable real and serious political change. The comedic tropes found in these TV shows allowed scholars to inject excitement into otherwise boring scholarship and find a clever way of recasting old rhetorical paradigms in a new light. My concern is that this scholarship had little effect on the ever-increasing, problematic practices of self-narration and knowledge seeking that occurs in our neoliberal society. The limited effect this surge of scholarship had is not necessarily the fault of these scholars, but instead the limits and restrictions placed on the genres and the discourses we are writing and working within. The fact that such a dynamic understanding of narrative, argumentation, and pedagogy could take place in parodic entertainment, be analyzed and appreciated by academia, but then not incorporated into academia in anyway is somewhat troubling. This should be doubly concerning during this era of the corporate academy.

As I’m writing, and this book nears completion, parodic and satirical fake news programs have expanded their reach and their demographics. Today Trevor Noah is the host of The Daily Show and Stephen Colbert has been bumped up to The Late Show where he continues to provide humorously poignant critiques of American culture and our political landscape. Furthermore, Daily Show alumni Samantha Bee hosts her own show Full Frontal and John Oliver hosts his own show Last Week Tonight. Other countries have boasted their own Stewarts and Colberts: Bassem Yousseff (Egypt) and Rick Mercer (Canada). The Onion and ClickHole continue to make us laugh through social media. Parodic and satirical fake news programs aside, the creation of parodic entertainment in the public sphere exploded into a rich and vibrant comedy scene that is thriving and providing cutting-edge critiques in a wide range of formats and platforms: TV shows and films (from major networks, cable networks, streaming services, YouTube, etc.), humorous books and spoof novels, stand-up/improv troupes (among various other live acts in a plethora of venues), podcasts, webisodes, memes, and other forms of humor on social media, etc. These entertainers employ a wide range of parody, biting political satire, irony, bathos, dark humor, anti/avant-garde humor, self-effacing humor, etc. They are able to put anything and everything under a microscope: the creator’s personal lives, societal issues, race relations, their local community, ← 3 | 4 → sexuality, mental illness, philosophical quandaries, etc. They can even lambast the faux-puritanical and neoliberal society that they profit directly from. It appears that parodic entertainment can act as a Trojan Horse within corporate institutions; e.g., the entertainment industry, academia, etc. Many of these the parodic examples have become part of the same neoliberal society that somehow unknowingly/uncaringly supports them, as long as these shows make money: some are produced by large production companies and distributed through major media platforms. So either parody is destroying neoliberalism from within, or parody is perpetuating neoliberalism, and we should learn to stop worrying and love neoliberalism [delete this last sentence before publication].3

However, before I go any further, I should briefly differentiate how these comedic tropes operate in order to clear up potential confusion and to clarify how I am using these terms.4 To briefly and insufficiently define parody, I should start by saying something to the effect of: the comedic rhetorical device known as parody occurs when the parodist fully dresses up within the form, gestures, tropes, etc. of its target (what it is being parodied) in order to comically critique or comment on its target and itself, and this interplay between itself and its target generates humor. Parody makes this dress up obvious through exaggeration and by taking its target (or target’s context) to its logical absurdity without ever (or rarely) disrobing. As it was highly fashionable to publish on the The Colbert Report and The Daily Show, I will use The Colbert Report as an example of parody that most of us are probably familiar with and The Daily Show as an example of satire, although at times these shows can effectively put both comedic devices to work. The Colbert Report qualifies as a parody because Stephen Colbert is a conservative pundit: the target here; i.e., he takes on the views of a conservative pundit and the humor is generated because he does so. Colbert takes these views to their logical absurdities for the viewer. For example, at any moment when Colbert’s parodic character ← 4 | 5 → is debating a Bill O’Reilly-type, he can simply agree with the O’Reilly-type because Colbert’s character is a conservative pundit. As Kafka writes, “Agreement is the best weapon of defense” (301). Often the absurdity of the O’Reilly-type’s position is better exposed when Stephen agrees and takes the stance to its logically absurd conclusion. Stephen is able to be something other than his true identity because he is not attached to it in that moment, because he doesn’t have to be, because that is not what the situation calls for. Colbert the person is not his opinions in this situation (if we ever truly are). By performing this move he is able to detach himself from the highly artificial battlefield before him, and understand that if there is such a thing as a real identity, it’s not worth using it during an encounter where nothing can be resolved (debating a character that will never admit defeat). So the act and the parody continues, rather than an attempt to get at the Truth of the matter, which would be impossible in this context and possibly impossible within our public sphere. In this way, the act, or the dress-up, becomes the only way to be genuine, or to preserve what might be thought of as a genuine-self (around friends, etc.). In a serious world one has to be radically inauthentic in order to be authentic, or more precisely, one needs to understand how to preserve authenticity within the inauthentic gestures that are necessary to move about in a serious world. Or perhaps put in yet another way, in a serious world you are inauthentic no matter what, so at best, you should embrace radical inauthenticity in order to be able to choose for yourself the authentic aspects of this persona and its message.

On The Daily Show, Jon Stewart establishes himself as himself (for the most part, or as a character of himself, etc.) and critically lampoons what he views as the ridiculousness around him. Satire both mimics its target and establishes itself outside its target. Therefore, satire builds its own base while putting its target on display and humorously pointing out its weaknesses. Satire makes its target foolish and absurd, thereby generating humor in the process. It is almost as if satire has something better in mind when it performs its critique: it wants to replace the absurdity of its target with something better. While satire attempts to replace its target with something better, thereby implying that there are right and wrong answers, parody can remain ambivalent to its target (whilst dressing up within its target by hiding in parentheses). So what would an ironic fake news pundit look like? Perhaps if a Bill O’Reilly-type (a pompous blowhard-type) announced, “Surprise! I was doing everything ironically!” However/unfortunately, this is not the reality we live in. Instead, we often see both Stewart and Colbert using irony: whenever they take a stance ← 5 | 6 → we know they do not truly believe, whenever they say something that directly contradicts an argument they just made, etc.

To further differentiate and qualify my descriptions of parody throughout this book, the following lists (not exhaustive) highlight works that best embody this form of parody. The main focus of these lists is on recent or undiscussed programming/streaming shows (some currently in production), although a few often-discussed-classics and parodies from other mediums are included. I’ve attempted to create a broad list of examples and tried not to repeat names (all Monty Python films, all Christopher Guest’s films, etc.). These shows represent a recent high-point in parodic programming/streaming, but are often overshadowed in academic literature by more politically enabling comedic fake news programs (labeled as satiric) that have been researched extensively. I will discuss these shows in further detail in Chapter Four, but I want to provide an opportunity for the reader to put this book down and go watch them. If these shows are more entertaining than this book, I recommend you watch them and stop reading this book (but only if you still recommend this book to others and leave a good review).

TV Series/Streaming Programs

Monty Python’s Flying Circus (Crt. Chapman, Cleese, Idle, Jones, Palin, Gilliam, 1969–1974)

Saturday Night Live (Crt. Michaels, 1975–Present)

Mr. Show with Bob & David (Crt. Odenkirk, Cross, 1995–1998)

The Colbert Report (Crt. Colbert, Karlin, Stewart, 2005–2014)

Robot Chicken (Crt. Green, Senreich, 2005–Present)

30 Rock (Crt. Fey, 2006–2013)

Tim and Eric Awesome Show Great Job! (Crt. Heidecker, Wareheim, 2007–2010)

The Sarah Silverman Show (Crt. Silverman, Harmon, Schrab, 2007–2010)

Children’s Hospital (Crt. Corddry, 2008–2016)

Portlandia (Crt. Armisen, Brownstein, Krisel, 2011–2018)

NTSF:SD:SUV (Crt. Scheer, 2011–2013)

Burning Love (Crt. Oyama, 2012–2013)

Details

- Pages

- X, 214

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433162664

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433162671

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433162688

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433162695

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14780

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (January)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2019. X, 214 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG