Unsettling the Gap

Race, Politics and Indigenous Education

Summary

In unravelling these diverse modalities of gap, the text illuminates the types of ruling binaries that tend to direct dynamics of power and knowledge in a settler colonial context. This reveals not only the features of the crisis of "Indigenous educational disadvantage" that the policy seeks to address, but the undercurrents of a different type of crisis, namely the authority of the settler colonial state. By unsettling the normalised functions of gap discourse the book urges critical reflections on the problem of settler colonial authority and how it constrains the possibilities of Indigenous educational justice.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- Advance Praise for Unsettling the Gap

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Images

- Abbreviations and Terminology

- Abbreviations

- Terms

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1. A Future with No More Gaps?

- Introduction

- The policy problem: The stubbornness of Indigenous ‘disadvantage’

- Colonisation and education

- Thinking history

- Policy and politics

- A gap

- The politics of naming

- No more gaps?

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 2. Racing the Gap: Concepts of Race in the (Settler) Colonial World

- Introduction

- Colonialism and race

- Settler colonial theory

- Power and authority

- Racing the gap

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 3. Questions of Time

- Introduction

- Histories of and in the present: Examining the policy, its history and its political effects

- ‘A historical knowledge of struggles’: The socio-political conditions of the present, the 1960s and the 1930s

- The recent past and the present: A political snapshot

- The late 1960s: A political snapshot

- The late 1930s: A political snapshot

- The past in the present

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 4. Standing on the Bridge: Critical Encounters with Ethics and Power

- The politics of knowledge

- The archives

- Reflections: June 2013, Melbourne

- The reading

- Reflections: January 2014, Melbourne

- The analysis

- Reflections: May 2014, Vancouver

- Reflections: June 2014, Birmingham

- Reflections: January 2015, Melbourne

- Standing on the bridge

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 5. Tracing the Gap: Constructions of Deficiency and Potential

- Introduction

- Deficiency and potential: Uplift, upgrade, closing the gap

- The discourse of deficiency

- The coupling of potential to deficiency

- Contestation and rupture: Interrupting the norm

- The logic of elimination: Correction, normalisation and epistemic dispossession

- Note

- References

- Chapter 6. Gauging the Gap: Converging Discourses of Measurement and Rank

- Introduction

- The ladder: Hierarchies of capacity

- Measurement and rank as tools used to indicate deficiency and potential

- Questioning the hegemony of measurement

- Colonisation and neoliberalism: Transnational forces of competition and race

- Notes

- References

- Chapter 7. The Right Side of the Gap: School, Nation, Inclusion, History

- Introduction

- School, nation, inclusion: Justice and equality, racism and prejudice

- National and social cohesion: The tensions of equality

- Inclusion: Whose responsibility, whose choice?

- The right side of history

- The iterative process of repetition of educational inequality

- References

- Chapter 8. Beyond Closing the Gap: Provocations for Thinking Otherwise

- Introduction

- Nation building and disadvantage: Terra nullius and closing the gap

- Failure and deficiency

- History and the present in addressing structural inequalities

- Difference and structural justice

- Settler colonialism, Indigenous education and decolonisation

- Notes

- References

- Author Biography

- Artist Biographies

- Index

- Series index

Image 1.1. Tracey Moffatt, Pioneer Dreaming, 2013, From the series ‘Spirit Landscapes’, Digital print on handmade paper, hand coloured in ochre, Edition of 8. Image 27 × 61cm. © Tracey Moffatt. Courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney.

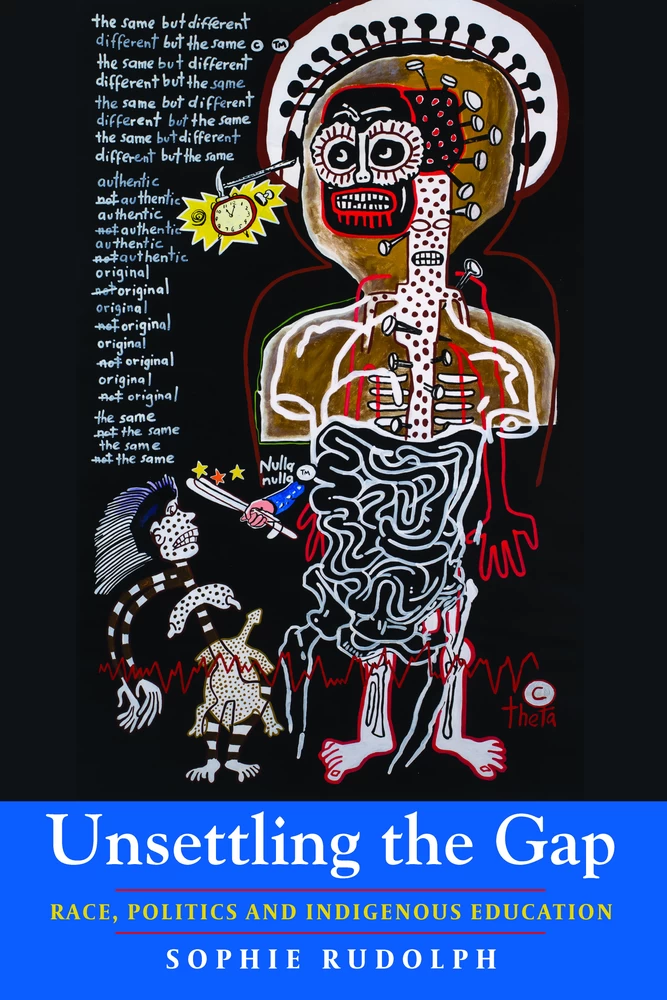

Image 2.1. Vernon Ah Kee, austracism, 2003, ink on polypropylene board, satin laminated, edition of 3. image 120 × 180 cm. ©Vernon Edward Ah Kee/Copyright Agency, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery. Photo: Carl Warner.

Image 3.1. Maree Clarke, Mutti Mutti/Yorta Yorta/Boon Wurrung peoples, Made from Memory (Nan’s house) 2017 (detail), holographic photograph, 100 × 150 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Purchased 2017 in recognition of the 50th Anniversary of the 1967 Referendum. ©Maree Clarke. Image courtesy the artist and Vivien Anderson Gallery, Melbourne. ← ix | x →

Image 4.1. Brenda L. Croft, Only shadows remain, 1998, Ilfachrome digital print. Image: 49 × 76cm. ©Brenda L. Croft/Copyright Agency, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Niagara Galleries, Melbourne.

Image 5.1. Gordon Bennett, untitled, 1989, oil and acrylic on canvas, six panels each 30 × 30 cm. ©The Estate of Gordon Bennett. Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Bennett and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, gift of Doug Hall 1993. Photo: Richard Stringer.

Image 6.1. Brook Andrew, Australian, born 1970, Vox: Beyond Tasmania, 2013, wood, cardboard, paper, books, colour slides, glass slides, 8 mm film, glass, stone, plastic, bone, gelatine, silver photographs, metal, feather. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Yvonne Pettengell Bequest, 2014 (2014.58). ©Brook Andrew/Copyright Agency, 2018. Courtesy the artist and National Gallery of Victoria.

Image 7.1. Fiona Foley, Annihilation of the Blacks, 1986, wood, paint, plant fibre, hair, adhesive, feather, 2670 mm × 2045 mm × 857 mm. National Museum of Australia, Canberra. © Fiona Foley. Courtesy the artist and National Museum of Australia. Photograph: George Serras, National Museum of Australia.

Image 8.1. Stewart Hoosan, Mayawagu—Freedom Fighter, 2013, acrylic on linen. Image 88 × 120 cm. ©Stewart Hoosan. Courtesy the artist.

Image 8.2. Nancy McDinny, Destruction of our Bush Tucker, 2013, acrylic on linen. Image 101 × 120 cm. ©Nancy McDinny. Courtesy the artist.

Image 8.3. Jack Green, Same Story Settlers Miners, 2013, acrylic on linen. Image 66 × 84 cm. ©Jack Green. Courtesy the artist.

Abbreviations

Terms

As we all know, no work is ever the product of a single person. And while I take full responsibility for the analysis and research developed in this book, I also thank those who have influenced and supported me in large and small, knowing and unknowing ways, throughout the process.

I would like to begin by acknowledging the Wurundjeri and Boonwurrung of the Kulin Nations on whose unceded land I have been privileged to walk and work, while writing this book. I would also like to acknowledge that writing of this book has, in addition, occurred on the lands of the Dja Dja Wurrung, the Larrakia, the Eora and the Darug, as well as the Musqueam of ‘Canada’. I pay my respects to the peoples of these Nations—and their elders past, present and emerging—who retain deep cultural, intellectual, spiritual and historical connections to their lands and continue to defy the constraints and violence of colonialism.

My thanks go to the many librarians and archivists who assisted me throughout the research phase for this work in Melbourne, Canberra, Brisbane and Sydney. To those who hosted me in Vancouver and Birmingham during a study trip in 2014 and to the organisers and participants of the Histories of the Education Summer School in Umea in July of that year—thank you for your insights and interest, especially Ian Grosvenor for suggestions ← xv | xvi → for engagement with artworks. Thanks also to the University of Melbourne for granting me an Overseas Research Experience Scholarship to assist in undertaking the travel.

Thank you to the artists who have allowed me to engage with and reproduce their artworks as openings for each of the chapters of the book. Your interest in the project has been encouraging and your work continues to inspire me. Also, thank you to the gallerists and representatives of the artists who I have worked with to organise the production and copyright licencing of the images.

Thank you to my PhD advisory committee who watched this project develop from a seed of an idea to its current form and offered thoughts and challenges to make it a richer piece of work. To Julie McLeod and Fazal Rizvi as supervisors—thank you for your time, energy and suggestions; and to Johanna Wyn and Julie Evans—thank you for your guidance. I would also like to extend my thanks to the examiners of my PhD thesis—Alison Jones and Roland Sintos Coloma—your comments, provocations and suggestions have enriched the work.

I would like to acknowledge the work of Julie McLeod on the historical debates about education in the 1930s, which has influenced my thinking. I thank her for giving me access to her archival sources and drawing my attention to the account of the Education in Pacific Countries, by Felix M. Keesing (1938), while I was a research assistant on her Australian Research Council funded project, ‘Educating the Australian Adolescent, 1930s–1970s’ (2009–2012), which she held with Katie Wright.

Details

- Pages

- XX, 204

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433159169

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433159176

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433159183

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433159145

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433159152

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14365

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (December)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2019. XX, 204 pp., 1 b/w ill., 9 color ills.