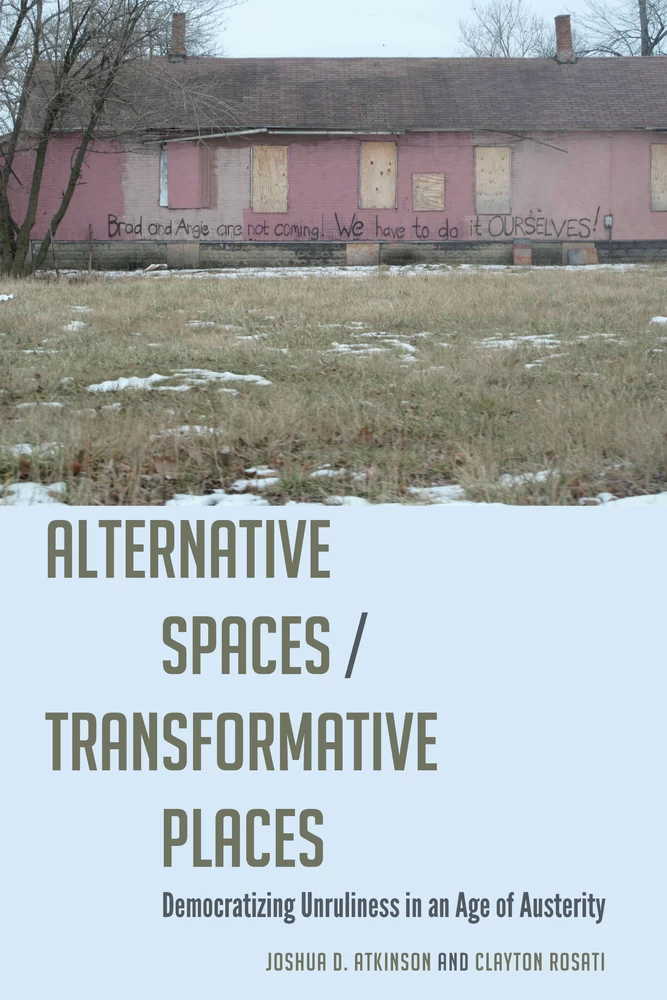

Alternative Spaces/Transformative Places

Democratizing Unruliness in an Age of Austerity

Summary

As such austerity has degraded infrastructure, depleted local economies, and poisoned neighborhoods, we feel citizens must be empowered to reclaim such unruly spaces themselves. The book explores different strategies for the democratization of such spaces in urban environments, and the potential and problems of each. Such strategies can create alternative perceptions and alter pathways through those spaces—even connect communities hidden from one another.

Students and scholars of urban communication and community activism, as well as human geography, will find the concepts and strategies explored in this book useful. The discussions related to austerity measures provide context for many contemporary neighborhoods and communities that have come to be neglected, while the chapters concerning unruly spaces provide explanations for the difficulty with such neglected or degraded environments. Finally, the illustration of different communicative strategies for the democratization of unruly spaces will demonstrate the possibilities for empowerment within communities that face such problems.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Figures

- Foreword

- Part I Introduction

- 1 Unruly Spaces, Cityscape & Communicative Cities

- 2 The Enclave at Wildcat Hollow

- Part II Global Forces—Austerity & Unruly Spaces

- 3 The Hidden Geographies of Flint

- 4 BART, Cairo, & Spaces of Exception

- Part III Rediscovering Lost Spaces in Germany

- 5 Memory Revival in Mannheim

- 6 Memory Modification at the DDR Museum

- Part IV Exploring a Hidden Geography in Detroit

- 7 Diffused Intertextual Production

- 8 Standpoint Performance Within the Intertext

- 9 Creative Narrative Appropriation

- Concluding Remarks

- Index

Figure 2.1. A new home in Wildcat Hollow

Figure 2.2. A gate at one of the new estate homes in Wildcat Hollow

Figure 5.1. Building at E4 Mannheim, present day

Figure 5.2. Stadtpunkt outside of the Rosengarten at Friedrichsplatz

Figure 6.1. A typical exhibit set into a partition at the DDR Museum

Crisis, Austerity, & the Pleasures of Cruelty

In late–2011, Steven J. Baum PC, a legal “foreclosure mill” operating in the suburbs of Buffalo, NY, issued a public apology. Not long before, an employee had leaked photos from the firm’s previous year’s Halloween party featuring other employees dressed in costumes mocking foreclosure victims, foreclosure rights attorneys, and a judge critical of their unscrupulous practices. In a 2012 legal settlement, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman noted that the Baum Firm “cut corners in order to maximize the number of its foreclosure filings and its profits” (New York State Attorney General, 2012a). According to Schneiderman, “From at least 2007 through sometime in 2009, Baum Firm attorneys repeatedly verified complaints in foreclosure actions stating, among other things, that the plaintiff was ‘the owner and holder of the note and mortgage being foreclosed,’ when, in many securitized loan cases, the Baum Firm did not have documentary proof that the plaintiff was the owner and holder of the note and mortgage” (New York State Attorney General, 2012a). In other words, the firm had been taking advantage of the massive housing crisis by collecting fees from huge banks and foreclosing on homes under false, shaky, or incomplete rights to do so. But there was no soul-searching by Baum PC employees.

←ix | x→One of the most noteworthy pieces of the Halloween carnival of contempt for those evicted by the crisis was its construction of a “shantytown” within which the costumed foreclosure processers (most not lawyers) held signs reading: “*@!$%^&(* Foreclosure! I’m current!!” and “3rd Party Squatter. I lost my home and I was never served!!” The signs displayed a perverse pleasure in cruelty, which was still abhorrent then and is revoltingly commonplace now. If not an admission of guilt, carnivals of this kind at least trace the complex contortions demanded by systems of debasement rather than simply reflecting poor taste.1 Not only did the 2007 economic crisis bring to a head the contradictions of key trends within millennial capitalism, it transformed homes and communities across the United States (and the world) at the hands of eviction officers armed with papers processed by firms like Baum. But, even further, the crisis forced an ideological reckoning with a set of assumptions about the free market, responsibility, and economic ethics. In this new impoverished environment, some acted to resist and restrain predatory capitalism, and some found even greater resonance with democratic socialism. In other instances, however, people confronted this reckoning with additional contempt for the poor, as well as people who were different or marginalized. Illustrating the latter, part of the Baum firm’s temporary house of horrors was a row of mock “foreclosure sale” properties. And, they weren’t alone in their heightened reactionary contempt. While nationally, blame for the crisis was often leveled at the poor themselves (Gross, 2008), it was the foreclosure mills, state austerity policies, real estate developers, and those who were evicting them, that extended the crisis, rigging foreclosure auctions, transforming the shape of communities, and getting rich in the process (see Desmond, 2016).2 To look at transformations in the city is to see, not just bureaucratic evils, but in many corners of that seemingly banal system a sadistic devotion to it, to unfair rules, to social inequality, and to pain-by-bureaucracy. In many cases there was no banality to speak of—only lenders, developers, hedge fund managers, foreclosure processers, and others conspiring to wrest as much money and as many assets as possible from the socially vulnerable.

The impetus for this book came a few years earlier, seven or so hours west of Buffalo by car, across the US “rustbelt.” We had both started our new jobs at Bowling Green State University in 2007, just south of Toledo and Detroit, when we encountered a landscape twisting under pressures from connected forces. We found our shared interests in the material-ideological dimensions of cities and urban landscape piqued by the various struggles that were developing over the redefinition of places, over the contending claims to their ←x | xi→popular meanings, and over the physical re/construction of neighborhoods and communities as part of those contending definitions. Detroit also seemed to have a kind of artificial distance from our (relatively) rural campus, just one hour north of us on I–75. At that time, it seemed like another world, where few in northwest Ohio seemed to go or commit research efforts as a matter of rustbelt solidarity or otherwise. In Detroit’s struggles, we found a chaotic spectrum of kindness and frustration, which engendered different versions of hope and long-term imaginations of the past and future.

Since the formal crisis and our research on the city, the Detroit landscape has transformed wildly in some places (e.g., Corktown’s gentrification, the new “Chinatown,” the Little Caesar’s Arena, state imposed “emergency financial management” and municipal bankruptcy) and has stagnated in others (e.g., nearly triple the national poverty rate, almost double the eviction rate, housing at hyper-vacancy rates). When we started our writing on cityscape, Detroit was popularly seen as an “unruly” place, as out of bounds or a frontier to be tamed, explored, and developed. Alistair Bonnett (2014), in his book Unruly Places, marshals this term to describe disorganized sites that people feel are peculiar, scary, or different. But Bonnett, like many self-described psychogeographers and urban explorers, approaches unruliness from a rather sentimentalist and exoticizing starting point. For instance, echoing popular and scholarly criticisms of suburbanization, sprawl, and corporate urbanism, Bonnett explains: “The rise of placelessness, on top of the sense that the whole planet is now minutely known and surveilled, has given this [pervasive] dissatisfaction a radical edge, creating an appetite to find places that are off the map and that are somehow secret, or at least have the power to surprise us” (p. xiv). But one need only be a foreclosure processer to see that simply finding “off the map” places is a relatively dull edge for radicalism.

This was something intimated to us early in our Detroit work, the world doesn’t need more ruin pornographers. Coverley (2009) looks at things similarly in his Psychogeography, in which he notes:

If psychogeography is to be understood in literal terms as the point where psychology and geography intersect, then one of its further characteristics may be identified in the search for new ways of apprehending our urban environment. Psychogeography seeks to overcome the processes of “banalisation” by which the everyday experience of our surroundings becomes one of drab monotony. (p. 13)

But Coverley doesn’t stop there. Channeling filmmaker Patrick Keiller, he critically notes:

←xi | xii→… psychogeography [is] increasingly preoccupied with its own practices as an end in themselves, no longer the tool of any larger political or even cultural project but simply a self-contained and self-immersed movement with little significant impact on the environment whose redevelopment it has so vocally denounced. (pp. 28–29)

Was it possible to simply wander (anymore or ever) in the city or explore urban ruins for the satisfaction of personal “surprise” or excitement? After the financial collapse? After gentrification? After the Detroit water crisis? After the lead crisis in Flint?

In a similar timeframe, Wark (2013) writes rousingly in the Spectacle of Disintegration about some of the main popularizers of wandering, drifting, dérive, or exploring the psychogeographies of cities, Guy Debord and the Situationist International movement:

Debord’s sometime comrade Raoul Vaneigem famously wrote that those who speak of class conflict without referring to everyday life, “without understanding what is subversive about love and what is positive in the refusal of constraints, such people have a corpse in their mouth.” Today this formula surely needs to be inverted. To talk the talk of critical thought, of biopolitics and biopower, of the state of exception, bare life, precarity, of whatever being, or object oriented ontology without reference to class conflict is to speak, if not with a corpse in one’s mouth, then at least a sleeper. Must we speak the hideous language of our century? (pp. 4–5)

And perhaps we might say to those simply seeking excitement in the city, without contemplating the violence of capital’s circulation or of class conflict are engaging in a kind of celebration of suffering—though, certainly not as conscientiously contemptuous as the Baum firm’s Halloween party or as naively “self-immersed” as ruin porn. Still they are, so to speak, walking on corpses that were immiserated under capitalism by homelessness, food insecurity, and “austerity suicides” (Mitchell, 2018). Between 2007 and 2011, the Baum foreclosure mill filed over 50,000 New York cases (Morgenson, 2011). The New York Attorney General’s (2012b) office reported that, “an average of 1 in 10 mortgages [was] at risk of foreclosure. The approximate number of individuals living in homes that [were] either in foreclosure or at risk of foreclosure [exceeded] the populations of Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse combined.” The stakes are high in our urban landscapes and we must always see the brutal within the banal.

This is the post-recession world. Poor. Put out. Pissed. Prone to verkakte saviors. Admittedly, it’s not too different from the pre-recession world. The rules of this current world are bound to austerity, to diminished public services, ←xii | xiii→to forced municipal bankruptcies, to more privatization, and even to the criminalization of private debt (i.e., return of debtors’ prison, see ACLU 2018). Austerity must not just be seen mathematically (granted, at times actual math would be a treat!) or philosophically. Rather, austerity has to also be understood emotionally, as a visceral impulse to tough love—like the conversations one hears at strange family holidays, full of hidden grudges, disproportionate hostility, and proud recollections of long-past suffering as the rationale for the torment of a new group of children.

Blyth (2013) notes in a Foreign Policy feature that “Austerity is a seductive idea because of the simplicity of its core claim—that you can’t cure debt with more debt. This is true as far as it goes, but it does not go far enough” (p. 43). In his book, Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea, Blyth (2015) invokes Quiggin’s notion of “zombie economics,” or “economic ideas that will not die despite huge logical inconsistencies and massive empirical failures” (p. 10). Blyth explains this in the following:

[Austerity] is a zombie economic idea because it has been disproven time and again, but it just keeps coming. Partly because the commonsense notion that “more debt doesn’t cure debt” remains seductive in its simplicity, and partly because it enables conservatives to try (once again) to run the detested welfare state out of town, it never seems to die. (p. 10)

Indeed, beyond the evidence that austerity doesn’t work, the inequality, the instability, and the asymmetrical burden it places on the poor, have, as Blyth notes, dangerous implications. As a case in point, amid the ongoing horror of Flint’s toxic water supply, to remark of austerity programs’ fiscal savings is not only obnoxious but misleading, given the additional health and infrastructural expenses it caused. And this is the key. Whatever impulse there is to tally up the balance sheets betrays the idea’s most dangerous play: its incessant rationality (e.g., how much money is a life worth?). But, the idea of austerity also feels good to certain segments of the capitalist world, or segments of the capitalist “mind” (whatever that might be). As we starve one beast, we feed another (Bartlett, 2007).

Despite the delight contemporary populist politics seem to take in cruelty, mass movements sprout against that tide: The Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, the Detroit Water Brigade, Black Lives Matter, the national Incarcerated Worker’s Strike, Me Too, Standing Rock water protectors, Medicare for All, and the list goes on. The contest for the future will implicitly be urban, as it is now, struggling to redefine the social meanings of common ←xiii | xiv→resources, pollution, debt, inequality, public speech and protest, and development in so-called poor and rich countries alike. The contested cityscapes of the future will be implicitly devoted to what many urbanists call “the right to the city” as a political question: who has the right to control our social products and, ultimately, the production of our own social nature (e.g., Harvey, 2013; Lefebvre, 2003; Mitchell, 2003, 2018). This is a technological, legal, and ideological problem. It is also implicit in contemporary considerations of democracy.

One of the key ideological contradictions of the neoliberal era, of the era of austerity and cruel pleasures, is the mismatch between the physical capacity of the world economic system and the deprivation experienced by so many. Why less, given our productive capacity? Who makes those choices? The National Conference to Defeat Austerity, held in Detroit in March, 2018, recently defined their counter-narrative as the following: “defeating the war being waged by the banks, corporations, and government against the workers and oppressed” (Ikonomova, 2018, np). When we look at the delight in contempt and cruelty that the Baum firm’s Halloween party represented, its mockery of destitute lives and its crass cynicism, we see the depth of the political crisis at hand. But perhaps we might even hold some sympathy for the employees whose livelihoods are beholden to making people homeless. Should we hold those office workers in a contrary contempt? Or do we see carnivals of that kind as expressions of the emotional repetitive stress injuries of neoliberal capitalism? Beyond marking enemies, it is out of austerity’s and neoliberal capitalism’s contradictions with concepts like dignity, equality, the commons, and even democracy that we find new meanings built for and into our urban resources. And it is on that platform against austerity and against the pleasures of cruelty, for abundance and sustainability, for equality and innovation, that new struggles for meaning can find the city as something to be remade along the path of their aspirations. That platform must target the force of the prevailing systems of cruelty—the rights to the city and to our very nature that banks, corporations, and political budget mongers currently occupy. It is on this platform that the struggle for democratization must proceed.

All of which leads to our collaborative research efforts, which formed the foundation for this book. In 2010 we took keen interest in the city of Detroit, and efforts to reimagine the spaces and places therein. Clayton, a geographer, was attentive to the global forces that had scarred the physical environment and cityscape, as well as counter narratives that challenged those forces. Josh, a communication scholar, was fascinated with the lived experiences of ←xiv | xv→people who utilized those counter-narratives, as well as the ways in which they co-constructed them—and experienced them—through media and performative practices. That initial project concerning Detroit illustrated the intersection of neoliberalism, austerity policies, digital media, activism, and communicative practices of resistance. The findings from that overarching project produced the following publications:

• Atkinson, J. D., & Rosati, C. (2012). DetroitYES! and the fabulous ruins virtual tour: The role of diffused intertextual production in the construction of alternative cityscapes. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 29, 45–64.

• Atkinson, J. D., Rosati, C., Berg, S., Meier, M., & White, B. (2013). Racial politics in an online community: Discursive closures and the potentials for narrative appropriation. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 37(2), 171–185.

• Atkinson, J. D., Rosati, C., Stana, A., & Watkins, S. (2012). The performance and maintenance of standpoint within an online community. Communication, Culture & Critique, 5, 618–635.

What is more, these studies initiated other research that explored rural communities, cities in Germany, telecommunication policies, and lead poisoning in Flint, Michigan. Those efforts were published in the following:

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 256

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433157578

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433157585

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433157592

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433157561

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14149

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (March)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. XVIII, 256 pp., 6 b/w ill.