Memory and Postcolonial Studies

Synergies and New Directions

Summary

Combining theoretical discussion with innovative case studies, the chapters consider various postcolonial politics of memory (with a focus on Africa); diasporic, traumatic and «multidirectional memory» (M. Rothberg) in postcolonial perspective; performative and linguistic aspects of postcolonial memory; and transcultural memoryscapes ranging from the Black Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, from overseas colonialism to the intra-European legacies of Habsburg, Ottoman and Russian/Soviet imperialism. This far-reaching enquiry promotes comparative postcolonial studies as a means of creating more integrated frames of reference for research and teaching on the interface between memory and postcolonialism.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

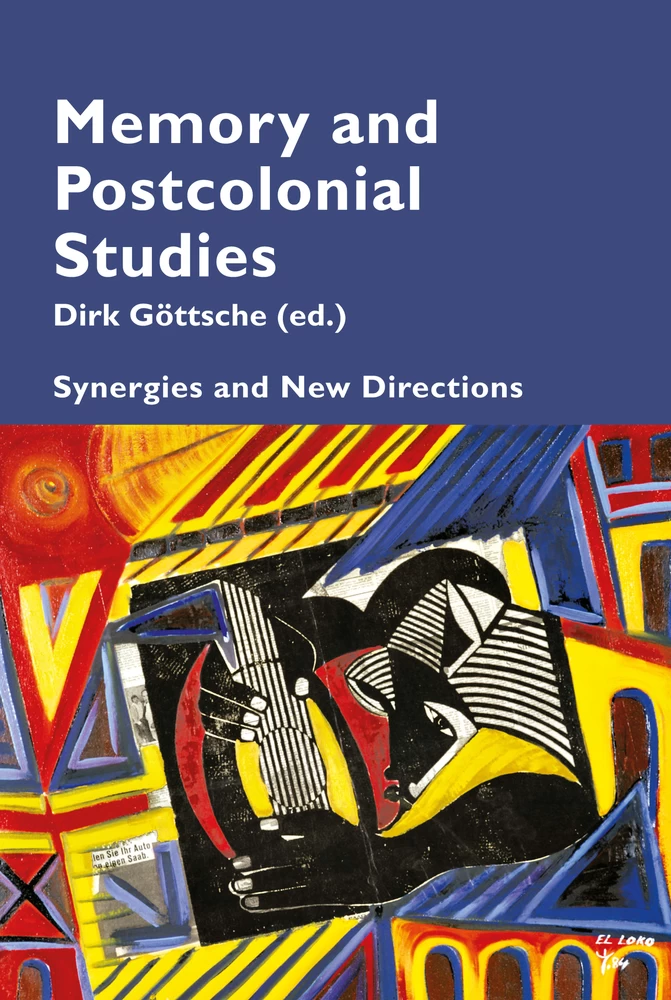

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editor

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I. Postcolonial Memory and History: African Case Studies

- History or memory? Postcolonial politics of memory in Bernhard Jaumann’s Der lange Schatten and M. G. Vassanji’s The Magic of Saida (Dirk Göttsche)

- Cross-cultural memory in postcolonial contexts: European imperial heroes in twenty-first-century Africa (Berny Sèbe)

- The memory of German, French and British colonialism in Cameroonian postcolonial literature (Richard Tsogang Fossi)

- Memory and the contemporary postcolonial condition in José Eduardo Agualusa’s novel A General Theory of Oblivion (Emanuelle Santos)

- Part II. Postcolonial Memory and the Black Atlantic

- Long-memoried women: Slavery and memory in contemporary Black women’s poetry (Abigail Ward)

- “My name is not Tom”: Josiah Henson’s fight to reclaim his identity in Britain, 1876–1877 (Hannah-Rose Murray)

- Traumatic memory in the art of Freddy Rodríguez (Stephanie Lewthwaite)

- Part III. Diasporic and Multidirectional Memory

- “Effacer mes mauvaises pensées”: Memory, writing and trauma in Nina Bouraoui’s autofiction (Antonia Wimbush)

- Pulled in all directions: The Shoah, colonialism and exile in Valérie Zenatti’s novel Jacob, Jacob (Rebekah Vince)

- Proximate spaces of violence: Multidirectional memory in Rachid Bouchareb’s films Days of Glory and Outside the Law (Alex Hastie)

- The reconstruction of history and cultural memory in contemporary Chinese-American women’s life-writing: A comparative study of two memoirs (Fang Tang)

- Part IV. Memory and Multi-Layered Identities in Postcolonial Perspective

- Literary history and memory in Quebec (Rosemary Chapman)

- Post-national Portuguese literature: Reconfiguring the imperial master narrative (Anneliese Hatton)

- Writing food and food memories in Turkish-German literature by Renan Demirkan, Hatice Akyün and Emine Sevgi Özdamar (Heike Bartel)

- Part V. The Emergence of Postcolonial Memory: Language, Media and Performance

- “2 October is not forgotten”: Tlatelolco 1968 massacre and social memory frameworks (Victoria Carpenter)

- Writing Rwanda: The languages of killing and suffering (Christopher Davis)

- Digital storytelling and performative memory: New approaches to the literary geography of the postcolonial city (Spencer Jordan)

- Part VI. Memory and Continental Imperialism in Comparative Postcolonial Studies

- Comparative Postcolonial Studies: Southeastern European history as (post-) colonial history (Monika Albrecht)

- Collective trauma, transgenerational identity, shared memory: Public TV series dealing with the Ottoman Empire and Anatolian refugees in Greece (Yannis G. S. Papadopoulos)

- The working memory in contemporary Latvian culture and society: Between postcolonialism and postcommunism (Benedikts Kalnačs)

- The Danube archipelago: The hydropoetics of river islands (Vladimir Zorić)

- An empire remembered? Collectivization and colonialism in Mukhamet Shayakhmetov’s memoir The Silent Steppe (Alun Thomas)

- Notes on contributors

- Index

- Series Index

Memory and

Postcolonial Studies

Synergies and New Directions

PETER LANG

Oxford • Bern • Berlin • Bruxelles • New York • Wien

Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Names: Göttsche, Dirk, 1955- author.

Title: Memory and postcolonial studies : synergies and new directions / Dirk Göttsche.

Description: 1 Edition. | New York : Peter Lang, [2018] | Series: Cultural memories ; 9 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018020644 | ISBN 9781788744782 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Postcolonialism. | Decolonization. | Collective memory. | Memory.

Classification: LCC JV51 .G67 2018 | DDC 325/.3--dc23 LC record available at

https://lccn.loc.gov/2018020644

Cover image: El Loko, “Landscape I/Landschaft I” (1984); oil, collage on wood, 95 x

107 cm (ELL033). Reproduced courtesy of ARTCO Gallery.

Cover design: Peter Lang Ltd.

ISSN 2235-2325

ISBN 978-1-78874-478-2 (print) • ISBN 978-1-78874-479-9 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-1-78874-480-5 (ePub) • ISBN 978-1-78874-481-2 (mobi)

© Peter Lang AG 2019

Published by Peter Lang Ltd, International Academic Publishers,

52 St Giles, Oxford, OX1 3LU, United Kingdom

oxford@peterlang.com, www.peterlang.com

Dirk Göttsche has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Editor of this work.

All rights reserved.

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright.

Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without

the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution.

This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming,

and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Dirk Göttsche is Professor of German at the University of Nottingham, Member of the Academia Europaea, Honorary President of the International Raabe Society, and Co-Director of Nottingham’s Research Priority Area “Languages, Texts and Society”. He completed his PhD (1986) and his Habilitation (1999) at the University of Münster. Recent publications include Remembering Africa: The Rediscovery of Colonialism in Contemporary German Literature (2013), (Post-) Colonialism across Europe (co-ed., 2014) and Handbuch Postkolonialismus und Literatur (co-ed., 2017).

About the book

In the postcolonial reassessment of history, the themes of colonialism, decolonization and individual and collective memory have always been intertwined, but it is only recently that the transcultural turn in memory studies has enabled proper dialogue between memory studies and postcolonial studies. This volume explores the synergies and tensions between memory studies and postcolonial studies across literatures and media from Europe, Africa and the Americas, and intersections with Asia. It makes a unique contribution to this growing international and interdisciplinary field by considering an unprecedented range of languages and sources that promotes dialogue across comparative literature, English and American studies, media studies, history and art history, and modern languages (French, German, Greek, Portuguese, Russian, Serbian-Croatian, Spanish).

Combining theoretical discussion with innovative case studies, the chapters consider various postcolonial politics of memory (with a focus on Africa); diasporic, traumatic and “multidirectional memory” (M. Rothberg) in postcolonial perspective; performative and linguistic aspects of postcolonial memory; and transcultural memoryscapes ranging from the Black Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, from overseas colonialism to the intra-European legacies of Habsburg, Ottoman and Russian/Soviet imperialism. This far-reaching enquiry promotes comparative postcolonial studies as a means of creating more integrated frames of reference for research and teaching on the interface between memory and postcolonialism.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Contents

Part I. Postcolonial Memory and History: African Case Studies

History or memory? Postcolonial politics of memory in Bernhard Jaumann’s Der lange Schatten and M. G. Vassanji’s The Magic of Saida

Cross-cultural memory in postcolonial contexts: European imperial heroes in twenty-first-century Africa

The memory of German, French and British colonialism in Cameroonian postcolonial literature

Memory and the contemporary postcolonial condition in José Eduardo Agualusa’s novel A General Theory of Oblivion←v | vi→

Part II. Postcolonial Memory and the Black Atlantic

Long-memoried women: Slavery and memory in contemporary Black women’s poetry

“My name is not Tom”: Josiah Henson’s fight to reclaim his identity in Britain, 1876–1877

Traumatic memory in the art of Freddy Rodríguez

Part III. Diasporic and Multidirectional Memory

“Effacer mes mauvaises pensées”: Memory, writing and trauma in Nina Bouraoui’s autofiction

Pulled in all directions: The Shoah, colonialism and exile in Valérie Zenatti’s novel Jacob, Jacob

Proximate spaces of violence: Multidirectional memory in Rachid Bouchareb’s films Days of Glory and Outside the Law

The reconstruction of history and cultural memory in contemporary Chinese-American women’s life-writing: A comparative study of two memoirs←vi | vii→

Part IV. Memory and Multi-Layered Identities in Postcolonial Perspective

Literary history and memory in Quebec

Post-national Portuguese literature: Reconfiguring the imperial master narrative

Writing food and food memories in Turkish-German literature by Renan Demirkan, Hatice Akyün and Emine Sevgi Özdamar

Part V. The Emergence of Postcolonial Memory: Language, Media and Performance

“2 October is not forgotten”: Tlatelolco 1968 massacre and social memory frameworks

Writing Rwanda: The languages of killing and suffering

Digital storytelling and performative memory: New approaches to the literary geography of the postcolonial city←vii | viii→

Part VI. Memory and Continental Imperialism in Comparative Postcolonial Studies

Comparative Postcolonial Studies: Southeastern European history as (post-) colonial history

Collective trauma, transgenerational identity, shared memory: Public TV series dealing with the Ottoman Empire and Anatolian refugees in Greece

The working memory in contemporary Latvian culture and society: Between postcolonialism and postcommunism

The Danube archipelago: The hydropoetics of river islands

An empire remembered? Collectivization and colonialism in Mukhamet Shayakhmetov’s memoir The Silent Steppe

Index←viii | ix→

Figure 1. Heroes melted in concrete: the new appearance, Soviet-style, of the former ‘Pavois’ in Algiers. Photo © Berny Sèbe.

Figure 2. Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo: the Brazza mausoleum with the 8-metre-high statue of the explorer in front. Photo © Berny Sèbe.

Figure 3. Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo: modern representation of the French conquest in the main atrium of the Brazza mausoleum, by a local African artist. Photo © Berny Sèbe.

Figure 4. Koulouba, Bamako, Mali: “Place des explorateurs” in May 2013. Photo © Adrian Hunt.

Figure 5. NourbeSe Philip, “Zong! #1”, Zong! Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2008, 3–4 (p. 3).

Figure 6. NourbeSe Philip, “Ventus”, Zong! ibid., 78–98 (p. 80).

Figure 7. Freddy Rodríguez, The Great Dictator, 1990. Acrylic and collage on canvas, 52 x 66 inches. Reproduced with permission of the artist.

Figure 8. Freddy Rodríguez, Paradise for a Tourist Brochure, 1991. Acrylic, sawdust and collage on canvas, 66 x 60 inches. Reproduced with permission of the artist.

Figure 9. Freddy Rodríguez, Crime Scene, Search Area, 1991. Acrylic, sawdust and collage on canvas, 42 x 28 inches. Reproduced with permission of the artist.←ix | x→

Figure 10. Corporal Abdelkader reads a Nazi propaganda leaflet, encouraging African soldiers to switch sides and win their independence. Days of Glory (2006, Rachid Bouchareb). Reproduced with permission from Filmbankmedia.

Figure 11. Corporal Abdelkader is diegetically framed outside of history, officially forgotten, as he is cleansed from the whitewashed image of victory. Days of Glory (2006, Rachid Bouchareb). Reproduced with permission from Filmbankmedia.

Figure 12. The bidonville of Nanterre, just outside of Paris, serves as a base for the Souni family and as an iconographic connection to other spaces of containment. Outside the Law (2010, Rachid Bouchareb). Reproduced with permission from StudioCanal.

Figure 13. Đorđe Krstić, Babakai, 1906. Oil on canvas, the National Museum of Serbia.

Figure 14. Ivan Generalić, Paysage fluvial, 1964. Oil on glass.

Figure 15. Zuko Džumhur, “Adakale”, 1997.

Figure 16. Momo Kapor, Ada, 1985.

Figure 17. Underground (1995, Emir Kusturica), © Artificial Eye.←x | xi→

This volume is largely based on papers given at the symposium on “Memory and Postcolonial Studies: Synergies and New Directions” hosted by the University of Nottingham’s interdisciplinary Research Priority Area “Languages, Texts and Society”1 on 10 June 2016. The editor would like to thank all those involved in this event, and in particular the contributors of this volume, including those who newly joined the project in autumn 2017, for developing their contributions in line with the overarching aim of exploring the multifaceted interface between Memory Studies and Postcolonial Studies. Special thanks go to Adam Horsley and Jacob Runner for their meticulous copy-editing of all chapters, including linguistic support for those authors who are not native speakers of English. I am also grateful to the University of Nottingham and its School of Cultures, Languages and Area Studies for generously providing the funding required at various stages of the project. Finally, I would like to thank Laurel Plapp and her team at Peter Lang for their care in seeing this volume through to publication.←xi | xii→ ←xii | 1→

1 See <http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/languagestextssociety/index.aspx>.

Memory and postcolonialism

The interface between the themes of memory and (post-) colonialism has recently emerged as a powerful catalyst for rethinking and expanding postcolonial research at a time when some of the premises of postcolonial theory since the 1970s are beginning to be challenged while literary, historical and interdisciplinary research in the field continues to expand internationally. Exploring the connections between memory and (post-) colonialism from both ends, Memory Studies and Postcolonial Studies are entering into a highly productive dialogue that gives new momentum to both fields of study. At the same time, memory has been an integral part of postcolonial discourse from the very beginning. Since the emergence of postcolonial theory and research in the wake of Edward W. Said’s Orientalism (1978)1 the memory of colonial experience and history, and the critique of the politics of memory relating to the colonial period, have been part and parcel of research in this interdisciplinary and international area. Postcolonial discourse uses memory – both individual and collective – to promote critical knowledge of the history of colonialism, raise awareness of its continuing impact in the present, and work towards political, social and cultural decolonization in a globalized, interconnected and yet conflict-ridden world that continues to be marked by colonial legacies such as racism, asymmetrical power relations and uneven access to resources and opportunities. In The Empire Writes Back (1989), for example, now a classic of postcolonial theory, Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin maintain that “the rereading and the rewriting of the European historical and fictional record is a vital and inescapable←1 | 2→ task at the heart of the post-colonial enterprise”.2 Stuart Hall goes one step further when he places “the retrospective re-phrasing of Modernity within the framework of ‘globalisation’”3 at the heart of “the postcolonial project”4 and its historical mission. Graham Huggan follows the same line of argument when he speaks of “Postcolonialism as Critical Revisionism”.5 As postcolonial inquiry revisits the past from the perspective of late twentieth- and twenty-first-century concerns, there is thus an intrinsic link between memory and the postcolonial reassessment of history both in the global South and in the global North. Postcolonial research exploring this link bridges the gap between the memory work of individuals, activists, groups, literature, film and other cultural production and a postcolonial politics of memory that works towards overcoming (the legacies of) colonial conditions and discourses. If we follow the German historian Heinrich August Winkler, who understands “Geschichtspolitik” [the politics of history] as the “use of the past for the purposes of the present” (“Inanspruchnahme von Geschichte für Gegenwartszwecke”) and as “a struggle for the right kind of memory” (“Kampf um das richtige Gedächtnis”),6 then memory and the politics of memory have been core elements of postcolonial activism and research from the very start. In calling the politics of history ‘politics of memory’, English is indeed more explicit than the German in indicating the links between memory and postcolonialism that underpin the synergies between Postcolonial Studies and Memory Studies explored in this volume.←2 | 3→

In historical perspective, it is worth noting that both of these interdisciplinary and international Cultural Studies paradigms, Postcolonial Studies and Memory Studies, developed very much at the same time. Said’s Orientalism, often seen as the turning point from earlier anti-colonial to postcolonial research, was published in 1978; the essays collected in Homi K. Bhabha’s The Location of Culture (1994) were first published between 1985 and 1992; Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s essay “Can the subaltern speak?” first appeared in 1988.7 The French historian Pierre Nora developed his concept of lieux de mémoire [sites of memory], which became central to the emergence of Memory Studies, in his seven-volume series Les Lieux des mémoire, published between 1984 and 1992; German historian Reinhart Koselleck’s influential study Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time (Vergangene Zukunft, 1979) was published in English translation in 1985; Jan Assmann published his seminal Das kulturelle Gedächtnis (Cultural Memory, 2007) in 1992.8 In his introduction to The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Literary Studies Neil Lazarus links the rise of Postcolonial Studies to “the end of the era of decolonization” and the disappointment of the hopes invested in the independence of the former European colonies during the 1960s, as well as “the downturn in the fortunes and influence of insurgent national liberation movements and revolutionary socialist ideologies in the early 1970s”.9 Marking much the same historical moment, Pierre Nora regards the start←3 | 4→ of the global “memory boom”10 in the 1980s as the result of the collapse of previous expectations of progress and growth, the disillusionment of earlier (both liberal and Marxist) political visions, and the fundamental crisis of historical thought that resulted from these developments.11 There is thus a global historical context for the intrinsic links between Memory Studies and Postcolonial Studies.

Despite such historical parallelism it has taken well into the new millennium for proper dialogue between Memory Studies and Postcolonial Studies to develop. Michael Rothberg’s monograph Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (2009) arguably played a key role in taking research at the interface between Memory Studies and Postcolonial Studies to a new level; it also acts as a significant frame of reference for many of the chapters in this volume. Before mapping out recent dialogue between both research methodologies in the arts and humanities, however, it is worth noting that synergies between memory and postcolonialism have been equally productive inside as outside academia, in political activism, literature and culture. In the case of Germany, which I will use as an example, historian Jürgen Zimmerer explicitly criticized the adaptation of Pierre Nora’s concept of lieux de mémoire in German historiography, in Étienne François and Hagen Schulze’s collection Deutsche Erinnerungsorte [German sites of memory] (2001),12 for failing to include the colonial theme. Arguing that Postcolonial Studies and Memory Studies share a common ground that has hitherto been ignored, his collection Kein Platz an der Sonne: Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte [No place in the sun: memory sites of German colonial history] (2013)13 applies the concept to memory sites of German←4 | 5→ colonial history. These range from key tropes of the colonial imagination (such as the tropical jungle or the famous moor of chocolate makers Sarotti) through imperial politics (e.g. the Congo conference in Berlin, 1884–5) to institutions (such as the Völkerkundemuseum [ethnological museum] and the Askari soldiers, the African mercenaries serving among the German Reich’s colonial troops in East Africa); the volume also includes memorials and the renaming of streets along with key players in colonial politics and culture (such as the author Frieda von Bülow, the ‘mother’ of the colonial novel in German, and officer Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, a key figure in the colonialist revisionism of the Weimar period). Ulrich van der Heyden and Joachim Zeller’s volume Kolonialismus hierzulande: Eine Spurensuche in Deutschland [Colonialism in this country: retracing its history in Germany] (2007)14 also builds on Nora and exemplifies the most successful format of both historiographical and popular engagement with colonial history through memory: the concept of Spurensuche, of retracing the remains/evidence of the colonial past in the postcolonial present, be they physical, linguistic or cultural. Since the 1990s regional historiography and activists have applied the concept of postcolonial Spurensuche to a whole range of German cities such as Hamburg, Berlin, Cologne, Freiburg and Bielefeld, producing exhibitions, books and websites that spread postcolonial historical awareness throughout society while at the same time intervening in Germany’s politics of memory from a postcolonial angle.15 Similar syner←5 | 6→gies of postcolonial and memory concerns can be seen in local initiatives to replace colonial street names with names which promote postcolonial awareness. One prominent example is the renaming of the former Groebenufer in Berlin in 2009, originally named after the first governor of Brandenburg/Preußen’s short-lived colony of Großfriedrichsburg in West Africa, Otto Friedrich von der Groeben (1657–1728). The street is now called May-Ayim-Ufer to commemorate the late Afro-German poet and feminist Black activist May Ayim (1960–96).16 Synergies between Postcolonial and Memory Studies also feed into research about the cultural history of colonialism, such as postcards, stamps, toys and other items of material history that survive in popular culture today.17 At the same time, contemporary German literature since the 1990s has rediscovered colonialism as both a historical and a memory theme, often using formats – such as metafictional historical narrative or the transgenerational family novel – which explicitly reflect upon the significance of the colonial past for the present.18 The centenary in 2004 of Germany’s genocidal colonial war in South-West Africa, today’s Namibia, further accelerated integration of colonial history in Germany’s culture of memory, giving postcolonial concerns unprecedented public resonance.

Similar examples could be given from high-profile debates about the memory of colonial history in France – most notably about the Algerian←6 | 7→ war of independence and President Chirac’s ill-fated ‘memory law’ of 2005 –, from the context of Anglo-Indian memory contests, from Italy, or various African countries.19 The chapters in this volume discuss a range of further examples from European, African, Caribbean and American scenarios which bring memory and postcolonialism together in cultural geographies that span the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean, or indeed the continents of Europe and Asia.

Memory and Postcolonial Studies in literary and cultural studies

In the arts and humanities, the synergies between memory and postcolonialism are better understood if we briefly consider some of the developments in Memory Studies that strengthen the interface with Postcolonial Studies, and vice versa, in particular in literary and cultural studies, the disciplinary field at the heart of this volume. Alongside the new interest in memory emerging in historiography, as seen in the research, for example, of Nora, Winkler and Zimmerer above, there was the rediscovery since the 1980s of the work of French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, who explored the social dimension of memory in studies such as On Collective Memory (French 1925, English 1992) and The Collective Memory (French 1950, English 1980).20 Halbwachs’←7 | 8→ finding that all personal memory is deeply embedded in the material and cultural life of the social groups to which we belong has been crucial for the proliferation of memory research across the arts and humanities since the 1990s. Understanding memory as a socially determined construction of the past is of course equally central to the postcolonial critique of colonial history and its legacies. The chapters in this volume will give ample evidence of the “Memory Contests”21 involved in the postcolonial renegotiation of colonial history through memory across literatures and cultures in Africa, Europe, the Americas and Asia. Memory Studies research into the forms and functions of collective memory therefore opens the door to dialogue with Postcolonial Studies.

Building on Halbwachs, the notion of “collective memory” refers to the family as the smallest social unit, as well as to larger groups (milieus, generations, institutions, classes, religious or ethnic groupings) and societies or nations as a whole. In order to allow for further differentiation, the German Egyptologist Jan Assmann and his wife Aleida Assmann, a literary and cultural scholar, introduced the much-debated distinction between “communicative” and “cultural memory”: communicative memory is memory of the recent past shared by those living at a particular time who then pass this memory on orally (for the age of the internet one should probably add the social media); by contrast, cultural memory is subject to social rituals and political codification reflected in recurrent historical narratives, institutions of commemoration and often conflicting politics of memory.22 The role of collective memory in nation-building – both in nineteenth-century Europe and in postcolonial nations of the global South – is a prominent instance of the emergence of cultural memory,←8 | 9→ which is rarely uncontroversial. Indeed, the debates about postcolonial memory since the era of decolonization – within the former colonies, in the former colonial centres, and between the two – are a prime example of how collective memory in the shape of cultural memory involves memory contests which rival the protracted process of Vergangenheitsbewältigung [the working-through of the past] in Germany with regard to National Socialism and the Holocaust, probably still the most prominent themes of international Memory Studies. Cultural memory is typically “fragmented and pluralized”;23 it gives rise to the “struggle for the right kind of memory” that defines the politics of memory,24 in which literature and other cultural productions have a crucial role. Concepts developed in the context of Holocaust studies are therefore often equally productive in postcolonial research. One prominent example is the notion of “postmemory”, developed by Marianne Hirsch25 to define the specific memory discourses of those whose parents or grandparents went through traumatic historical experiences, such as the Holocaust, slavery or colonialism, passing elements of such historical trauma on to their children and grandchildren. As the colonial period within a particular country or language area passes into history, postmemory becomes a major theme in postcolonial writing – often in the form of life-writing or autofiction – that revisits the colonial past and its legacies from a late twentieth- or twenty-first-century perspective. Several of our case studies advance research into postcolonial postmemory. This is also one of the points where Postcolonial Studies interact with Trauma Studies,26 as some of the chapters in this volume indicate.←9 | 10→

Details

- Pages

- XII, 584

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788744799

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788744805

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788744812

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781788744782

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14024

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (June)

- Keywords

- slavery imperialism Black Atlantic English studies American studies Modern Languages intra-European colonialism Indian Ocean Africa trauma Memory studies Postcolonial studies Comparative literature Cultural memory Colonialism diaspora

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2019. XII, 584 pp., 13 fig. col., 4 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG