Italian Orientalism

Nationhood, Cosmopolitanism and the Cultural Politics of Identity

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I The Reception of the Oriental Renaissance in Risorgimento Italy

- Chapter 1 Orientalism versus Classicism? Debating ‘Europeanness’ in Risorgimento Discourse

- Chapter 2 Orientalism and the Romantic Risorgimento: The Manifestos of Giovanni Berchet and Ludovico Di Breme

- Chapter 3 Negative Orientalism: Giacomo Leopardi’s Neoclassical-Romantic Protest Against European Modernity

- Part II Indic Orientalism and Aryanism in Italy from Unification to Fascism

- Chapter 4 Italian Orientalistica: Indology, Aryan Ideology and the Philological Sciences of Euromania

- Chapter 5 Race, Religion and Colonialism in Italian Orientalism and Anthropology: From the Indo-European to the Eurafrican

- Chapter 6 Positivist Indic Orientalism in Anton Giulio Barrili’s Il tesoro di Golconda and Giosuè Carducci’s ‘All’Aurora’

- Chapter 7 Guido Gozzano’s Verso la cuna del mondo: Modernism, Existentialism and British India

- Epilogue Orientalism and Propaganda in Fascist Italy: Nation, Race and Empire

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Italian Orientalism

Nationhood, Cosmopolitanism

and the Cultural Politics of Identity

PETER LANG

Oxford • Bern • Berlin • Bruxelles • New York • Wien

Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: De Donno, Fabrizio, author.

Title: Italian Orientalism : nationhood, cosmopolitanism and the cultural politics of identity.

Description: New York : Peter Lang, 2019. | Series: Italian modernities | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018044642 | ISBN 9781788740180 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Orientalism--Italy. | Italy--Civilization--Indic influences. | Italy--Civilization--19th century. | Italy--Civilization--20th century. | Italian literature--History and criticism. | Political culture--Italy. | India--Study and teaching--Italy.

Classification: LCC DG450 .D38 2018 | DDC 303.48/24505409034--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018044642

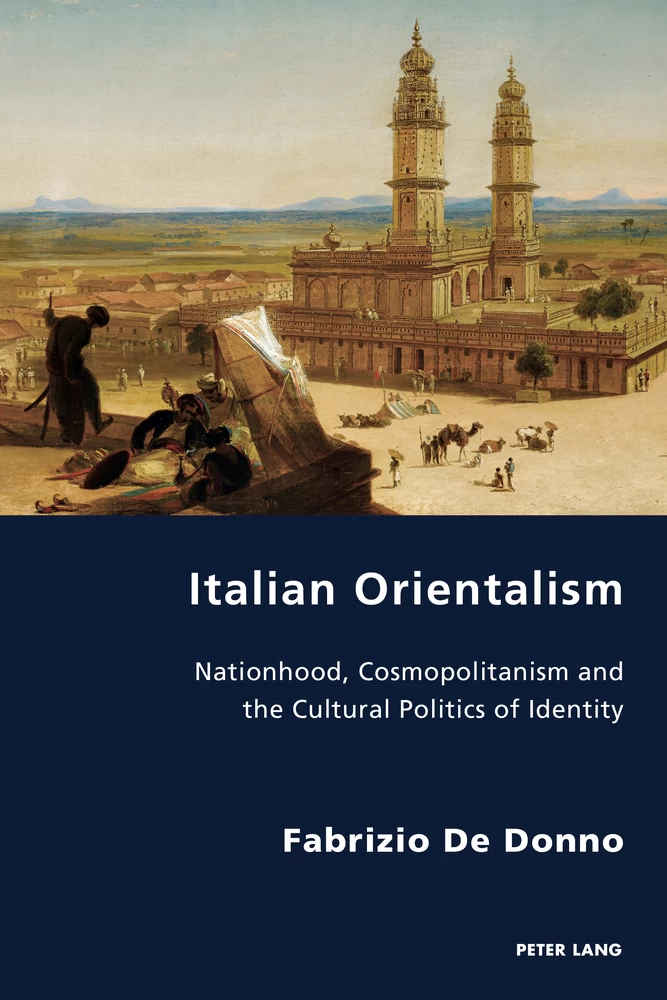

Cover image: Oriental landscape with Mosque, attributed to Alberto Pasini (1826–1899). Wikimedia Commons.

Cover design by Peter Lang Ltd.

ISSN 1662-9108

ISBN 978-1-78874-018-0 (print) • ISBN 978-1-78874-019-7 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-1-78874-020-3 (ePub) • ISBN 978-1-78874-021-0 (mobi)

© Peter Lang AG 2019

Published by Peter Lang Ltd, International Academic Publishers,

52 St Giles, Oxford, OX1 3LU, United Kingdom

oxford@peterlang.com, www.peterlang.com

Fabrizio De Donno has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this Work.

All rights reserved.

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright.

Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution.

This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming, and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Fabrizio De Donno is Lecturer in Italian and Comparative Literature at Royal Holloway, University of London.

About the book

The on-going debate on the legacies of modern European Orientalism has yet to fully consider its Italian context. Italian Orientalism is an interdisciplinary and transnational study both of the reception of European Orientalism in Risorgimento Italy, and of the development of an Italian Orientalist expression in the post-unification and fascist periods. The pan-European phenomenon is approached in its epistemological, aesthetic and political dimensions, while focusing on India and Indology as triggers of the so-called ‘Oriental Renaissance’ and the Indo-European or Aryan idea. Fabrizio De Donno analyses the relationship between Orientalist scholarship and literary aesthetics in their related European and Italian contexts, mapping their interaction with linguistic, racial, religious and colonial thought. Paying particular attention to some of the major Italian intellectual, academic and literary figures of the time – from Giovanni Berchet, Giacomo Leopardi and Carlo Cattaneo, to Angelo De Gubernatis, Cesare Lombroso, Carlo Conti Rossini, Giosuè Carducci, Guido Gozzano and others – the book explores how Orientalism and Aryanism emerge as major if controversial discourses of modernity. They provide the rhetorical tools of identity politics which, it is argued, are central to notions of Italian nationhood, cosmopolitanism and Euromania.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Contents

Part I The Reception of the Oriental Renaissance in Risorgimento Italy

Orientalism versus Classicism? Debating ‘Europeanness’ in Risorgimento Discourse

Orientalism and the Romantic Risorgimento: The Manifestos of Giovanni Berchet and Ludovico Di Breme

Negative Orientalism: Giacomo Leopardi’s Neoclassical-Romantic Protest Against European Modernity

Part II Indic Orientalism and Aryanism in Italy from Unification to Fascism

Italian Orientalistica: Indology, Aryan Ideology and the Philological Sciences of Euromania ←v | vi→

Race, Religion and Colonialism in Italian Orientalism and Anthropology: From the Indo-European to the Eurafrican

Positivist Indic Orientalism in Anton Giulio Barrili’s Il tesoro di Golconda and Giosuè Carducci’s ‘All’Aurora’

Guido Gozzano’s Verso la cuna del mondo: Modernism, Existentialism and British India

Orientalism and Propaganda in Fascist Italy: Nation, Race and Empire

Index ←vi | vii→

This book began life as a PhD thesis at the University of Cambridge, and was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. I would like to thank my supervisor, Zygmunt Baranski, for his support and guidance throughout those years. I am also very grateful to Javed Majeed and Sir Christopher Alan Bayly (may he rest in peace) for their interest in this project, and for providing inspiration, illuminating conversations, and insightful feedback on my work over many years. I would like to thank my colleagues at Royal Holloway, University of London, for their encouragement and support. My thanks also go to the librarians of the British Library, London, and of the Istituto per l’Oriente, Rome. For their extensive comments on chapters of this book, I am deeply indebted to Robert S. C. Gordon, Charles Burdett, Francesca Orsini, James Williams, Marko Pajevic, Stefano Jossa and Daniela Cerimonia. Several friends provided cheerful and supportive conversations over the years in which I have been writing this book, and I am grateful to Nerina Eleuteri, Young-Sook Park, Kevin Phillips, Anna Morcom and Carlo Gallo. My deepest thanks go to Valeria Ceccarelli for her love, patience and companionship.

Some material has already appeared, in a different form, in the journal California Italian Studies. Parts of the Epilogue are a re-elaborated version of my article, ‘La razza ario-mediterranea: Ideas of Race and Citizenship in Colonial and Fascist Italy, 1881–1941’, which appeared in Interventions. International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 8.3 (2006). I am grateful for their permission to re-print some parts of this article. Finally, the translations from the Italian, unless otherwise stated, are mine. The translations from the French are by Michael Garvey.←vii | viii→ ←viii | ix→

Italian Orientalist scholar Francesco Gabrieli – Professor of Arabic at Rome University – wrote an article in 1965 entitled ‘Apology for Orientalism’,1 in which he defended the European Orientalist enterprise and stressed the relevance of Orientalist scholarship to European culture and civilisation. Gabrieli’s article was a response to another essay by Egyptian sociologist Anouar Abdel-Malek entitled ‘Orientalism in Crisis’2 (1963), which, more than a decade earlier than Edward Said’s publication of Orientalism (1978), had already raised concerns about Orientalism’s entanglement with imperialism, racism and Eurocentrism. In his piece, Abdel-Malek mapped the systematic way modern Western nations had developed a network of Orientalist institutions, learned societies and university chairs throughout Europe and the United States, while also pointing out that such practice had emerged out of the study of classical antiquity through the science of philology and the historical method. Interestingly, Abdel-Malek makes particular mention of Italian Orientalism under fascist disctator Benito Mussolini in order to address how such study had been accompanied by humiliation and occupation.3 Gabrieli responded by referring to Abdel-Malek’s claims as the East’s attempt ‘to make of European orientalism a scapegoat for its [the East’s] own problems, anxieties and pains’. While there were no doubt agents of colonial penetration among Orientalists – Gabrieli forcefully←1 | 2→ argued – there were many others whose interest was exclusively ‘scientific’. Among these Orientalists, Gabrieli mentions the Italian orientalist Leone Catani who, for instance, was against the Italian colonisation of Libya.4 Furthermore, in defence of the claims of Eurocentrism and of West-centred interpretations of world history, Gabrieli maintains that it was the West that developed ideas of history, science, evolution, and the spiritual heritage of mankind, and made a contribution to human thought in modern times; and in this sense, it had every right to retain a West-centred vision.5

Both Gabrieli’s and Abdel-Malek’s articles are now part of a reader of the most significant writings on Orientalism, A. L. Macfie’s Orientalism: A Reader (2000), published when, in the aftermath of Said’s Orientalism, the topic established itself as a major contemporary debate.6 It is to a certain extent surprising to note that both articles make particular mention of Italian Orientalism and that, even more startling, it was an Italian belated Orientalist, of all European Orientalists, to feel the need to legitimise the Western Orientalist enterprise so stubbornly and polemically. Indeed, it is not far-fetched to say that Gabrieli’s article and general view of Orientalism made their part in triggering Said’s writing of Orientalism. Was Italian Orientalism, then, a cultural phenomenon as harmless and uncontroversial, or anti-colonial as in the case of Caetani, and legitimately ethnocentric as Gabrieli claims it to be in relation to Orientalism at large?

This book attempts to reconstruct the modern Italian cultural engagement with European Orientalism and the Orient. It focuses on a central aspect in the cultural and intellectual history of Western and Italian Orientalism: the emergence and impact of the discipline of Indology and the way in which it gave way to a revival of the European interest in the Orient, and to the cultural politics of Indo-European identity in relation to European nationalisms. Raymond Schwab, in his famous book, La renaissance orientale (1950), has described the enthusiasm of nineteenth-century Europeans for all things Indian. More specifically, Schwab writes←2 | 3→ of the revival of Oriental Studies in Europe which followed the ‘discovery’ of Sanskrit manuscripts in India at the end of the eighteenth century – especially through the figure of British Orientalist Sir William Jones – and describes how such discovery brought to light the affinities between Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and the modern languages of Europe, and paved the way for the study of a new ‘Indo-European’ civilisation. The new discoveries led to a new interpretation of the history of civilisation, and especially of European civilisation, which was now said to have had its origins in ancient India. Schwab’s focus is primarily on how the European discovery of Indian antiquity became associated with Orientalist philology and European Romanticism, giving way to a general revival of the category of the ‘Orient’ at large, and bringing forth the idea of a new and truly universal humanism which moved beyond classical antiquity and the Mediterranean. Indeed, the Indic discoveries for Schwab gave way to what he has called a European ‘Oriental renaissance’, or ‘the revival of an atmosphere in the nineteenth century brought about by the arrival of Sanskrit texts in Europe’, which Schwab compares to the Italian Renaissance in that it ‘produced an effect equal to that produced in the fifteenth century by the arrival of Greek manuscripts and Byzantine commentators after the fall of Costantinople’.7 Schwab refers in passing to Italian Indological figures such as Angelo De Gubernatis, as well as the Piedmontese Gaspare Gorresio, as the Italian representatives of this new scholarship. However, he primarily focuses on British, French, German and Russian Orientalism and discusses how ‘the Romanticism of 1820’ that it inspired ‘was, like the Humanism of 1520, a Renaissance’.8 So how did the land of the Classical Renaissance react to this second Oriental renaissance?

Italian Orientalism aims to explore the impact of this Oriental renaissance in Italy over two significant moments: the pre-unification←3 | 4→ period, shaped by the Italian national movement of independence – the Risorgimento – examined in Part I; and the post-unification moment spanning the liberal and fascist periods, in Part II. Such division is helpful as the different nationalist concerns of the two moments are reflected in the different significance acquired by Orientalism and the Orient in Italian nationalist discourse between Risorgimento and fascism. Risorgimento Italy’s engagement with Orientalism, for instance, occurred within the framework of Italian discussions of independence, nationhood and modernity, and its cosmopolitanism reflected the more libertarian and emancipatory concerns of the period. On the other hand, with the development of a more aggressive nationalism in the post-unification years, the cosmopolitan dimension of Orientalism was more concerned with the definition of an Italian racial identity and debates around colonial expansionism, as well as with the process of secularisation and modernisation according to European standards. In fascist Italy, moreover, the relationship between Orientalism and national empowerment took on new extreme connotations through propaganda about empire, foreign policy and racialism. The emphasis on the different forms of Italian engagement with European Orientalism over the two parts of the book (which are nevertheless inextricably linked and illustrative of continuity as well), therefore, is useful as it reveals, through the overarching lenses of Orientalism, the ‘evolution’ of Italian nationalism and cosmopolitanism from emancipation to oppression in the cultural politics of Italian identity.

During the Risorgimento period, literary figures and intellectuals such as Giovanni Berchet and Ludovico Di Breme engaged with the general revival of the Orient as a category relevant to European culture, especially as an alternative to classical antiquity in discussions of modernity. Though Indic Orientalism had provided the greatest impulse in the Oriental renaissance, it was Jones’ work and legacy – as the embodiment of the transition from an older form of Oriental Studies to the new modern and ‘scientific’ pan-European Orientalism – that proved influential in Italy, especially due to the impact they had already had on European Romanticism. Italian Romantics like Berchet and Di Breme dealt with the Orient in the context of a Romantic nationalism in which Orientalism functioned as an anti-Classicist tool in debates about national emancipation, European identity,←4 | 5→ aesthetic innovation and modern nationhood in Italy. In this context, it was not only India the focus of interest, but also other Oriental areas such as Ottoman Greece and the Islamic Orient at large – cultural areas which, together with Arabia, Persia and the Far East, had been revived by the Oriental renaissance and the impulse provided by Indology. Giacomo Leopardi, too, especially in his dispute with Di Breme, engaged with the new trend in the context of the quarrel between Classicists and Romantics. However, Leopardi’s engagement was ambivalent, and despite his early rejections of Orientalism on the grounds that it was irrelevant to Italian identity, in time he subverted Romantic Orientalism and developed his own hybrid and existentialist form of Neoclassical-Romantic Orientalism in his protest against modernity and the meaninglessness of life. Moreover, during this first phase of reception, Italian intellectuals such as Gian Domenico Romagnosi and Carlo Cattaneo engaged with Indic Orientalism and the Indo-European concept in order to discuss notions of political freedom, national regeneration and world civilisation. They assessed the value and relevance of Indian civilisation to debates on the rebirth of Italian civilisation and European modernity, and rejected the Oriental renaissance as irrelevant in the land of the Classical Renaissance. Crucially, it is in the Risorgimento period that the first Italian chair of Indology was established in Turin with Gaspare Gorresio, which is the event that marked the birth of the new modern professional Italian Orientalism, or orientalistica.

After unification, and even more so after the beginning of the Italian colonial campaign in the 1880s, orientalistica witnessed fast growth on the model of the professional Orientalism of other European nations. It is at this stage that Orientalism’s enmeshment with Eurocentrism and racialism became more marked. Italian Orientalist scholarship developed in various fields – in conjunction with positivism and historicism first, and idealism afterwards – from Indology, comparative philology and mythology to linguistics, ethnology, and colonial scholarship (represented by figures such as Gaspare Gorresio, Graziadio Isaia Ascoli, Angelo De Gubernatis, Michele Kerbaker, Giacomo Lignana, Domenico Pezzi and Francesco Lorenzo Pullè). Other Orientalist fields that were revived by Indology and the new Indo-European or ‘Aryan’ concept ranged from Islamic Studies (Italo Pizzi and Carlo Alfonso Nallino), to Sinology (Carlo Puini), Turkology (Ettore←5 | 6→ Rossi), and Coptic Studies (Carlo Conti Rossini and Enrico Cerulli). Many of the Orientalists in Islamic and Coptic studies also wrote on law and ethnology in relation to the Italian colonies, while the whole discipline of Orientalism impacted on anthropology, craniology and criminology (through figures such as Cesare Lombroso and Giuseppe Sergi). Finally, fascism developed its own distinctive propagandistic style of Orientalist scholarship (Francesco Lorenzo Pullè, Carlo Formichi and Giuseppe Tucci), which was used to support fascist ideology, as well as foreign and colonial policies, and racial thought, sometimes serving anti-racism and sometimes racism, and culminating in racial legislation in the late 1930s.

In conjunction with this scholarly revival of Orientalism, a number of the most significant post-unification Italian writers showed an interest in popular and literary forms of Orientalism, and often these included travel writing and popular novels.9 India and Indology continued to prove←6 | 7→ inspirational and had an impact on popular, realist and modernist authors such as Anton Giulio Barilli, Giosuè Carducci, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Guido Gozzano. These authors often used the Orient as a platform to discuss Italian national rebirth and racial identity, as well as historical process and degeneration, colonial desire and imperial fantasies – especially in the context of British imperialism, which remained the ultimate colonial model for liberal Italy, before fascist Italy developed anti-British attitudes. These authors often drew on academic Orientalism in order to craft their own literary representations, thus contributing to the already strong link between professional and literary Orientalism.

The belatedness of modern Italian Orientalism meant that it borrowed heavily from British, French and German Orientalism. In this sense, instead of setting trends, it copied them. However, by contrast, the early modern Italian states had pioneered the European cultural engagement with the Orient, and post-unification Italian Orientalists in particular took pride in this early modern legacy. Orientalists such as Angelo De Gubernatis played on this long tradition of ‘Italian’ study of the Orient in order to establish a ‘primacy’ for Italy and legitimise the renewed interest in the modern Orientalist enterprise.10 If such a tradition dated back to Marco Polo’s Il milione (1300), it was during the Renaissance that the←7 | 8→ Italian states produced a vast amount of literature on the Orient, whether travel literature or other. Turkey and the Ottoman Empire, for instance, enjoyed a great deal of attention in theatre, from Niccolò Macchiavelli La mandragola (1518) to Gian Battista Della Porta’s La turca (1606) and Carlo Goldoni’s L’impresario della Smirne (1759). Egypt was the object of study of Renaissance works such as Marsilio Ficino’s Corpus Hermeticum (1471) and Pico della Mirandola’s Conclusioni (1486–7).11 Generally speaking, in particular in Pico’s Conclusioni, there is an attempt to demonstrate that paganism, Christianity, Judaism and Islam shared the same spiritual truths, thus laying emphasis on the Mediterranean links of these theologies.12 China was the topic of Jesuit authors such as Matteo Ripa and Matteo Ricci,13 whose Mappamondo (1584) was highly celebrated in China itself, while the Indian peninsula was narrated by several Jesuit travellers including Roberto De Nobili, Marco della Tomba, Filippo Sassetti and Pietro della Valle.14 Moreover, De Gubernatis was particularly keen to stress that Hebrew had been studied in the Italian peninsula since the times of the Romans, whereas Arabic and Turkish had been studied in the early modern Italian city-states which entertained several relations with Islamic states.15 According to the Orientalist, the first chairs of Arabic and Hebrew in the Italian peninsula were established by Raimondo De Pennaforte, the master←8 | 9→ of the Dominican Order, in Dominican convents around 1260.16 However, the University of Bologna, Europe’s first university, as well as that of Rome, established chairs of Arabic, Chaldean and Hebrew with the decree of the Vienna Council in 1311.17 De Gubernatis lists all the most important grammar books of these languages published since then in the Italian peninsula, either in Latin or Italian, particularly during the Renaissance, and goes on to give an account of the establishment of other chairs in the following centuries in a number of universities, such as Siena, Padua and Palermo, and religious institutions such as Catholic seminars, throughout the Italian peninsula until the time of writing.18 It is in the light of this long tradition that modern Italy, for De Gubernatis, should resume its central role in the European cultural engagement with the Orient.

As Amedeo Maiello has argued, in fact, modern Italian Orientalism, and Indology in particular, were ‘a valid means with which to bolster national prestige and to upgrade Italian culture to European standards.19 Although Maiello refers in particular to post-unification Orientalism, it is my argument in this book that Orientalism between Risorgimento and fascism served primarily the purpose of identity politics. During the Risorgimento, Orientalism attracted attention due to its popularity in Europe, but many Italian intellectuals rejected it in place of the more ‘significant’ classical identity associated with Classicism. At the same time, those authors that embraced Orientalism, especially in their Romantic nationalism, embraced a cultural identity that defined both Europeans and Orientals through a stark East-West divide. As Barbara Spackman has recently argued in her analysis of the fluid identities in narratives by Italian←9 | 10→ travellers to the Ottoman lands, Orientalism played with and created ‘identity’ for both Europeans and Orientals as its discourse ‘shaped not only those it “Orientalised”, but also those who it “Westernised” and “Europeanised”’.20 With the post-unification development of Italian Orientalism, the process of Italian identity-construction through Aryanism reached new racial heights. De Gubernatis, for instance, claimed to have travelled to India to experience first hand Italy’s roots in India and belonging to the family of Indo-European or Aryan peoples.21 He writes of how he wished to hear Sankrit being spoken by Indians themselves, and to witness the performance of all the ‘Aryan’ rites and ceremonies he had been reading about in the publications of his fellow European Orientalists. He declares his Aryanness thus:

Ario anch’io, ed italiano per giunta; ossia nato di un popolo nel quale, come nel greco e nell’indiano, Dio volle stampata un’ orma più profonda del genio ario, iniziato, dai miei giovani anni, alla conoscenza della più pura, della più antica e perfetta tra le lingue ariane, curioso indagatore della molta vita ideale che si cela e palpita in quel nobilissimo linguaggio, ero tormentato da un lungo e inquieto desiderio di sentirlo parlare nell’India stessa, di vedere fino a che punto gli antichi riti religiosi, le antiche credenze e consuetudini davano ancora forma e carattere all’odierna vita indiana; e←10 | 11→ finalmente, mi pungeva il desiderio di ritentare le prime sedi di quegli Arii pastori guerrieri e poeti per vedere in mezzo a qual natura … si manifestò da prima il genio lirico della nostra famiglia ariana.

[I am Aryan, and also Italian; that is, born of a people on whom, as in the Greek and the Indian, God wanted the deepest imprint of Aryan genius. Initiated, since my early years, into the knowledge of the purest, the most ancient and perfect among the Aryan languages [Sanskrit], and as a curious investigator of much of the ideal life which is concealed and palpitates in that most noble language, I longed to hear it spoken in India itself. I wanted to see to what extent the ancient rites, beliefs and customs still gave form and character to contemporary Indian life. And finally, I wished to visit the first settlements of those Aryan shepherds, warriors and poets; I wished to see amongst what nature … there originated the lyrical genius of our Aryan family.]22

Details

- Pages

- X, 366

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788740197

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788740203

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788740210

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781788740180

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11865

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (March)

- Keywords

- Italian Orientalism De Donno Cosmopolitanism cultural politics European Orientalism Euromania Nationhood

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2019. X, 366 pp

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG