(Re)narrating Teacher Identity

Telling Truths and Becoming Teachers

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

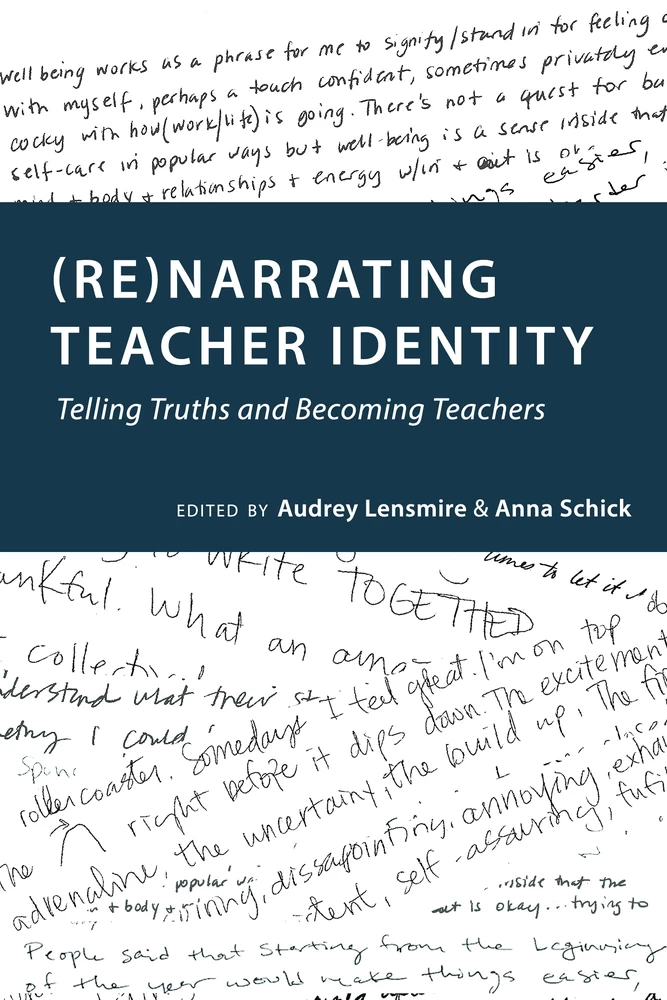

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Foreword (Angela Coffee, Erin Studelberg, and Colleen Clements)

- Chapter 1: On Becoming a Group of Women (Audrey Lensmire)

- Chapter 2: (Re)narration (Anna Schick)

- Chapter 3: Human/Teacher (Amanda Mohan)

- Chapter 4: We’re All Learning (Aubrey Hendry)

- Chapter 5: Teacher as a Role to Play (Marie D.S. Voreis)

- Chapter 6: Profound Thoughts on a Bathroom Wall (Samantha Scott)

- Epilogue (The Wild Horses)

- Series Index

BY ANGELA COFFEE, ERIN STUDELBERG, AND COLLEEN CLEMENTS

In the tentative heat of late June, our group (Angela, Erin, and Colleen) paused just outside of the home of Anna and our introduction to the authors of this book. The bringing together of our collectives had been in the works for a long time. Our two groups had both been working to use stories and writing to help us make sense of the role of women in education. Through conversations with Audrey and her husband Tim (who was also our former professor), the three of us had been catching glimpses into the work of these women teachers for the past several years. Many of the group’s questions, concerns, struggles, and hopes seemed to vibrantly connect with, overlap, and flow concurrently with our own. As we stood together at the base of the charming Victorian staircase that would lead us up to the group of women waiting inside, we lingered momentarily, anticipating the evening and conversations ahead, wondering at what might emerge.

Four years earlier, the three of us had found one another within a “Foundations of Education” course we had taken with Tim near the beginning of our doctoral programs at the University of Minnesota. Our shared interests and connections led us to develop independent studies, cultivate collectives, organize conference presentations, and create research projects together. Our experiences as a collective—a group deeply committed to one another and to challenging hetero-patriarchal white supremacy in education—radically transformed, illuminated, and nourished our journeys through graduate school. Collective memory work (Haug, 1987, 2008, n.d.), a feminist methodology for theorizing lived experiences and the ideologies entangled within them, has been foundational in our work together. In ← xvii | xviii → this process, individual written narratives of memory are collectively imagined, analyzed, and reimagined in an attempt to attune us to the dominant and normalizing narratives living within our stories and to create new possibilities for humanizing pedagogy. For us as white women teachers and researchers, this dependable community of care and deep accountability has been critical. Through this journey, our writing, our memories, our theoretical commitments, and our lives have been knit together in ways that blurred the edges of individual scholarship and enabled us to experience collective interdependence by sharing our stories with one another in deep trust, vulnerability, and desire for a better world.

As we stood at the foot of Anna’s staircase, Audrey burst out onto the porch. “I just knew you were here!” she declared. With a huge smile, she ushered us into Anna’s house. In the living room, we ate dinner and we talked. We sat in a circle and shared our stories with one another. Despite having never met before, there was a shared recognition and sense of support between our groups. We recognized in this collection of women the mutual care, generative and ongoing inquiry, and collective entanglement of stories that have characterized much of our work together. And we saw the power that collectivity has had for them as they have supported and challenged one another and reimagined their storied lives as women teachers.

In many ways the (re)narrated stories told in this book also resonate deeply with the three of us and connect to the work that we have done exploring our own lived experiences as white women teachers—a cohort historically constructed as caring nurturers of children, reproducers of patriarchy and white supremacy, and sources of cheap labor in the building of a colonial nation state. When we explore this narrative, we like to borrow Erica Meiner’s (2002) use of the “White Lady Bountiful” teacher trope: she is a virtuous, kind, and feminine woman who holds the future of the nation (her students) in her hands, and through that power reproduces hegemony. This narrative positions the white woman teacher in a contradictory role in the classroom: she is expected to control her students while being controlled by her superiors; she is the purveyor of a hetero-patriarchal culture that also limits and oppresses her as a woman. We recognize that the White Lady Bountiful lives in each of us and we see how her narrative persists through the stories, memories, and artifacts of the beginning women teachers in this book. In addition to her history, today the white woman teacher has also been constructed as a “problem” in schools because there are too many of her and because she is limited in her understanding of race outside the normalizing power of her whiteness. The stories in this book contribute much to this important conversation about the white woman teacher, how she is positioned as a “problem,” and the histories that live in and through her. Each chapter offers us a new understanding of how her construction also connects to another issue that many women and women teachers face: personal struggles with their mental and emotional health. ← xviii | xix →

The multitude of emotions and experiences of being a teacher that the authors here explore in their (re)narrated stories include anger, sadness, despair, addiction, hopelessness, anxiety, depression, discomfort, joy, relief, success, and desire. These affective experiences can and ought to be understood alongside both historical and contemporary narratives of white women teachers. As teachers and teacher educators, we share these feelings and have supported our students as they have, too. In particular, these stories have illuminated an important source of tension in our understanding of mental health. Because Western patriarchal culture centers the individual as knower, thinker, and doer, the emotional and embodied experiences of teachers easily become individualized, too. The dominant conception of mental health is of an individual’s journey, one that often holds us in a narrative of shame and self-blame rather than allowing us to disrupt, complicate, and expand our understanding of how and why we struggle. But like the historical, cultural, and political narratives of women teachers that live in and through us, our mental health can also be understood in more complex and collective ways. The stories in this book live in this tension between reproducing individual conceptions of mental health and seeking radical new possibilities for imagining self, including mental health, as a collective entanglement of systems, histories, and narratives.

Within this entanglement, we all embody multiple identities, both throughout our lives and from moment to moment as our daily contexts shift. This multiplicity of identities is present in any given moment. We are daughters, sisters, mothers, teachers, writers, and countless other labels we might give ourselves. When embodying the role of teacher, these other identities do not go away; yet, as articulated throughout this work, the socially constructed role of teacher seems to demand a suppression of the parts of us that do not easily comport with the White Lady Bountiful, the picture of the perfect maternal yet virginal presence, beneficently overseeing her charges, with infinite patience and caring, yet somehow able to remain neutral and detached, denying any expression of human emotion.

The chapters in this book are, in various ways, an attempt to interrupt the notion of a “perfect teacher” that suppresses all other identities. Persistent and dominant historical narratives, their influence strengthened by repetition and aimed at universalization, reproduce an (often problematic) unified identity: in this case, one that is either an attempt at embodying the role of “perfect teacher,” or an embrace of the complete failure to do so. As teachers, and as humans, we fall somewhere in between the two, and neither of them are a true representation of our lived experience. Our identities as we embody them are always partial and becoming, rather than whole and fixed. And yet there is something about the act of “storying” our experience that seems to bend us toward these universalizing narratives, that silences not only the more complicated parts of our own stories as white teachers, but also the counter-narratives from more marginalized perspectives. We have found that the act of narrating ← xix | xx → stories always risks the reproduction of dominant narratives; even as we attempt to disrupt them, we can find our stories harnessed to narratives of oppression and violence. Perhaps retelling our stories collectively, as the authors have done here, offers a way to interrupt that reproduction.

So, as you read these stories, we would like to offer an invitation. Our practice of collective storytelling and reading invokes in us a desire for you, too, to “read collectively.” This invitation to read collectively, even though you are likely reading this alone, encourages you to think about your own experience alongside the stories presented here, and your own multiple identities, attuned to the shifting spaces between and amidst your stories and the stories in this book. For it is in this act of reading and thinking collectively that we might better come to know the multitude of identities that reside in us all and the ways in which we perpetuate and resist universalizing stories—and in so doing, work to disrupt the power of the dominant narratives that continue to shape our storied existences.

Details

- Pages

- XXII, 102

- Publication Year

- 2017

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433140341

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433140358

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433140365

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433134982

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433134999

- DOI

- 10.3726/b10687

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (May)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2017. XXII, 102 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG