Globalization, Translation and Transmission: Sino-Judaic Cultural Identity in Kaifeng, China

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Abstract

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- A question of identity

- Historical background

- Periodising globalization

- Cultural hybridity as translation

- Transmissions of cultural identity

- Critical holism and integration of paradox

- Research methods

- Thesis structure and significance

- Challenging boundaries

- Translation and translator

- Part One: The Yicileye: translation and transmission of Sino-Judaic heritage (1000–1850 CE)

- Chapter One: A historiography of perception, representation and recognition of the Chinese Jews

- Lost in translations: the perspective of the Han Chinese

- Neighbours and rivals: the ambiguous link with the Hui

- The missionary encounters

- A case of mistaken identities

- Chapter Two: The epigraphic account: translations, confluences and transmissions

- Confluences of beliefs, values and practices

- The primacy of scholarship

- A speculative theology of the Chinese Jews

- An unanswered plea

- Chapter Three: Authenticity claims and authentication processes: the constructs of non-recognition

- Unauthenticated authenticity: The Black Hebrews

- Authenticity claims of the Kaifeng Jews

- The State of Israel’s Law of Return

- Matrilineal descent and conversion: pathways to Jewish identity

- The “Who Is a Jew?” controversy

- The historicity of the matrilineal principle

- China’s 1954 ethnotaxonomic Classification Project

- Official CPC policy on the status of Kaifeng Jews

- Part Two: Globalization and retranslation: the modern emergence of the Kaifeng Jews (1979 – present day)

- Chapter Four: Deconstructing the Kaifeng Construction Office and the reconstruction of culture

- Historical synopsis

- Evangelists, ethnologists, and entrepreneurs

- An irreconcilable threesome

- Fatal antagonisms

- The internecine politics of the Construction Office

- Chapter Five: The promises and constraints of Sino-Judaic cultural activism

- Anomalies of Sino-Judaic cultural heritage activism

- The supporting NGOs

- The Yicileye School: A Judeo-Christian impetus

- Beit Hatikvah: the transition to religious culture

- The Jewish Community of Kaifeng: an ephemeral figment of unity

- Jin Guangyuan: the case for aliyah

- Shi Lei: promoting history and tourism

- Guo Yan: the challenge to authentication

- Chapter Six: Sukkot and Mid-Autumn Festivals in Kaifeng: Conundrums at the Crossroads of Sino-Judaic Cultural Identity

- Arrival in Kaifeng

- Sukkot and mid-autumn festivals

- Revival, return or retreat

- Convergences, incongruities and the question of authenticity

- Historical memory and contemporary practice

- Epilogue

- Conclusion

- Problematizing Eurocentric boundaries

- Fast-forwarding Chairman Mao

- A banner for the nations

- Appendixes

- Appendix 1: Excerpt from 1489 stele

- Appendix 2: Excerpt from The Chinese Repository (1835)

- Appendix 3: 1850 letter of Kaifeng Jew Zhao Nianzu

- Appendix 4: 1953 CPC policy document on Kaifeng Jews

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

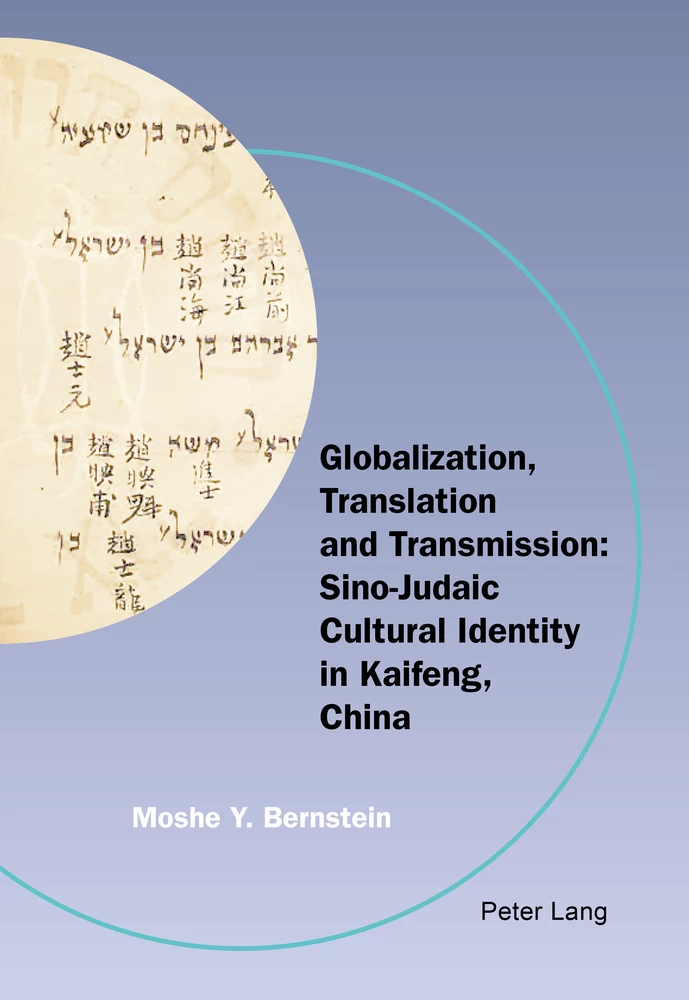

Title page: Kaifeng Memorial Book dating from the 14th century containing a register in both Hebrew and Chinese of the names of community members along with those of their male ancestors. The family rosters were included as a supplement to a siddur, or Hebrew prayer book.

(Hebrew Union College; http://huc.edu/research/libraries/collections/rbr/kaifeng)

In 1984, twenty-five years prior to my first encounter with the Jews of Kaifeng, the issue of conflicting translations of identity manifested itself through an unfortunate incident. In that year the Israeli government, in conjunction with a number of other international agencies, organised Operation Moses, the covert evacuation of more than 8,000 Ethiopian Jews, known as the Beta Israel, from their refuge in famine-stricken Sudan. I was then a full-time student in a rabbinic academy for married men of the Zans-Klausenburg Hassidic group located in the Old City of Safed in the Upper Galilee. As an American-born latecomer to orthodoxy, with a longstanding interest in the African diaspora and cultural diversity, I was intrigued at the arrival in Israel of Jews from Africa. That enthusiasm, however, was not shared by my rabbinic colleagues, all of whom hailed from more insular haredi (ultra-Orthodox) households and took a more circumspect view of the Chief Rabbinate’s decision to grant the Ethiopians Israeli citizenship under the Right of Return.

When I learnt that a group of these new immigrants had been transferred to a tentative absorption centre in Safed, I was keen to volunteer my family as a host to support the recent arrivals’ acclimation to their new environment. To that end, cognizant of the divergent view in the haredi world, I first consulted with the Rosh Kollel, the academy’s dean, to seek his permission to make contact with the group. The latter listened cautiously to my request but determined it was a significant matter that would require his consultation with the sect’s spiritual leader, the late Klausenburger Rebbe, who then resided in Netanya. Some days later the Rosh Kollel conveyed the Rebbe’s response that, regarding contact with the Ethiopian immigrants, I was permitted to conduct myself according to the guidelines of the local rabbinate. Since the Safed rabbinate, in concurrence with the ruling of the nation’s Chief Rabbi, had already approved the accommodation of the Beta Israel in Safed, I was given a somewhat ambivalent green light.

The next day I visited the absorption centre, set up in a former resort facility across from the municipality. I spoke with a woman in the administration office, who encouraged me to make direct contact with the ← 13 | 14 → residents. Strolling the grounds, I soon met a group of young teenage boys and attempted to strike up a conversation with them. This was not a simple task, as their native tongue was Amharic, and they had only begun to learn some basic Hebrew in their ulpan, the language program provided them. One of the boys, Daniel, who wore a yarmulke on his head and had studied a bit of English in his high school in Gondar, displayed more interest in our conversation and curiosity toward religious life in his new homeland. He happily accepted my invitation to join my family at our home for Shabbat lunch in two days’ time.

That Saturday, after the conclusion of the Shabbat morning service dressed in the customary Hassidic Sabbath finery of long, black bekishe and fur shtreimel, I walked through the Old City to the immigrant centre. The perplexed looks on the faces of the Ethiopians indicated their total unfamiliarity with my peculiar garb, otherwise a common feature of haredi neighbourhoods throughout Israel. Walking Daniel back to my home through the cobblestone lanes of the Old City, where he had yet to venture, I pointed out a few of the prominent sites and provided a historic overview of Safed in simple English. Religious passers-by on their way back from synagogue, dressed similarly to me, greeted us with expressions of bewilderment akin to those I had witnessed among the Ethiopian Jews.

At the Shabbat table, Daniel seemed to relish the home-cooked meal, taking a substantial second helping of the traditional cholent. He explained to us how his mother had died of illness several years earlier in Gondar, while his grandfather had passed away on the arduous overland trek to the Sudanese refugee camp the previous year. Several months earlier his father and younger siblings had moved to Addis Ababa, where they were lodging with paternal relations. He inquired about my tzitzit, the ritual fringes attached to the tallit katan, the undergarment worn by observant Jews; I explained the Torah commandment to attach fringes to any four-cornered garment and the subsequent rabbinic injunction to wear such a garment at all times. Before accompanying him back to the centre, I gave Daniel an extra tallit katan that had been tucked away in my closet. He was grateful for the gift, which he slipped on over his jersey.

No sooner had we exited the courtyard door when a small group of haredi Jews turned the corner of the adjacent alleyway. I recognized one of them as a rabbinic instructor and respected Talmudic scholar. A septuagenarian and one of the privileged few who had managed to escape from the ← 14 | 15 → notorious Vilna Ghetto to make his way to Palestine, he, along with three disciples escorting him, literally stopped in their tracks when they spotted us. For a brief moment, the old rabbi seemed utterly befuddled, but this confusion quickly yielded to a palpable fury. His facial complexion turning crimson from rage, he angrily shouted at me in Yiddish: “Er darf nisht truggen tziztzis! Er iz a goy!” He should not be wearing tzitzit! He is a goy!

Stunned at his reaction, I hastily guided Daniel past the group through the narrow alleyway, averting both the eyes and taunts of his detractors. Daniel’s doleful eyes searched mine questioningly; I told him not to worry, that everything was okay. However, his demeanour clearly indicated that he knew that it was not. We walked in relative silence back to the absorption centre. I let him know how much we enjoyed having him as our guest and that he was welcome to return to visit us at any time whether during the week or on Shabbat. However, he never did so. Several weeks later I learned that the Ethiopian contingent in Safed had been moved from their makeshift accommodation to various established immigrant centres throughout the country. We did not see Daniel again.

Details

- Pages

- 253

- Publication Year

- 2017

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034325431

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034325448

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034325455

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783034325462

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0343-2544-8

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (January)

- Keywords

- Sino-Judaic identity Kaifeng Jews cultural hybridity cultural identity ethnographic history Chinese history globalization authenticity claims cultural activism

- Published

- Bern, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2017. 253 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG