Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- Praise for Culture and Technology

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: On the Need for a Primer

- I: Culture and Technology: The Received View

- 1. The Power and Problem of Culture, The Power and Problem of Technology

- You Know a Lot About Culture

- You Know a Lot About Technology

- Technological Culture

- 2. Progress

- The Meanings of Progress

- Defining Progress

- The Goals of Progress

- The Importance of Criteria

- The Story of Progress in American Culture

- Two Concepts That Underpin and Help to Sustain This Story: Evolution and the Sublime

- The Uses of the Progress Story

- Promoting a Better Life

- Selling Us Something

- Judging and Controlling Others

- New Technology Equals Progress: To Question This Is Heresy

- Progress for Whom?

- Progress for What?

- 3. Convenience

- Convenience Is Another Story

- What Is Convenience?

- Convenience and the Body: From Meeting the Demands of the Body to Overcoming the Limits of the Body

- Wants and Needs

- When Convenience Isn’t

- The Time and Space of Consumption

- A Perpetual State of Dissatisfaction

- What the Future Holds

- 4. Determinism

- Technology as Cause: Technological Determinism

- Technology as Effect: Cultural Determinism

- Technological versus Cultural Determinism

- 5. Control

- Yes, We Have Mastery of Our Tools

- Control over Nature and the Environment

- Social Control

- No, Our Tools Are Out of Control

- Master and Slave: Trust and the Machine

- Autonomy

- Dependence

- Master and Slave

- AI, Expert Systems, and Intelligent Agents

- Conclusion

- II: Representative Responses to the Received View

- 6. Luddism

- Historical Luddism

- Contemporary Luddism

- 7. Appropriate Technology

- Sources and Varieties of AT

- AT and the Limited Understanding of Context

- 8. The Unabomber

- Kaczynski Must Be Insane

- The Unabomber Manifesto

- Lessons to Learn

- III: Cultural Studies on Technological Culture

- 9. Meaning

- So, Then, What Is Technology?

- Why Struggle with Meaning?

- Struggles over Meaning

- 10. Causality

- Beyond Determinism

- Mechanistic Perspectives on Causality

- Assumption #1: Technologies Are Isolatable Objects, That Is, Discrete Things

- Assumption #2: Technologies Are Seen as the Cause of Change in Society

- Assumption #3: Technologies Are Autonomous in Origin and Action

- Assumption #4: Culture Is Made Up of Autonomous Elements

- Simple Causality

- Symptomatic Causality

- Soft Determinism: A Variant of Mechanistic Causality

- Nonmechanistic Perspectives of Causality

- Assumption #1: Technology Is Not Autonomous, but Is Integrally Connected to the Context Within Which It Emerges, Is Developed, and Used

- Assumption #2: Culture Is Made Up of Connections

- Assumption #3: Technologies Arise Within These Connections as Part of Them and as Effective Within Them

- Expressive Causality

- The Essence

- Culture as Homogenous Totality

- Martin Heidegger and Jacques Ellul

- Articulation and Assemblage

- Conclusion

- 11. Agency

- From Causality to Agency

- Technological Agency

- Actors

- Delegation

- Prescription

- Network

- Issues with Actor-Network Theory

- Conclusion: Why Agency?

- 12. Articulation and Assemblage

- Technology as Articulation

- Technology as Assemblage

- Rearticulating Technological Culture

- Conclusion: Why Articulation and Assemblage?

- 13. Politics and Economics

- Politics and Economics as Assemblage

- Politics and Technology

- Network Culture

- Economics and Technology

- Rearticulating Politics, Economics, Technology

- 14. Space and Time

- Space and Time as Assemblage

- Space and Technology

- Time and Technology

- Modes: The Biases of Space and Time

- It’s Not Really a Gamble

- Conclusion: Why Space and Time?

- 15. Identity

- Identity as Assemblage

- Differentiating Machines

- Mobilizing Technologies to Rearticulate Identity

- Digital You

- The Distributed Self

- Conclusion

- 16. Critical Conjunctures

- From Articulation to Conjuncture

- The Current Conjuncture and Emergent Problematics

- The Problematic of Knowledge Production

- The Problematic of Privacy and Surveillance

- The Problematic of Environmental Degradation

- The Problematic of Being Human

- Ending with Moving Forward

- Notes

- Introduction: On the Need for a Primer

- Chapter One: The Power and Problem of Culture, The Power and Problem of Technology

- Chapter Two: Progress

- Chapter Three: Convenience

- Chapter Four: Determinism

- Chapter Five: Control

- Chapter Six: Luddism

- Chapter Seven: Appropriate Technology

- Chapter Eight: The Unabomber

- Chapter Nine: Meaning

- Chapter Ten: Causality

- Chapter Eleven: Agency

- Chapter Twelve: Articulation and Assemblage

- Chapter Thirteen: Politics and Economics

- Chapter Fourteen: Space and Time

- Chapter Fifteen: Identity

- Chapter Sixteen: Critical Conjunctures

- References

- Index

| ix →

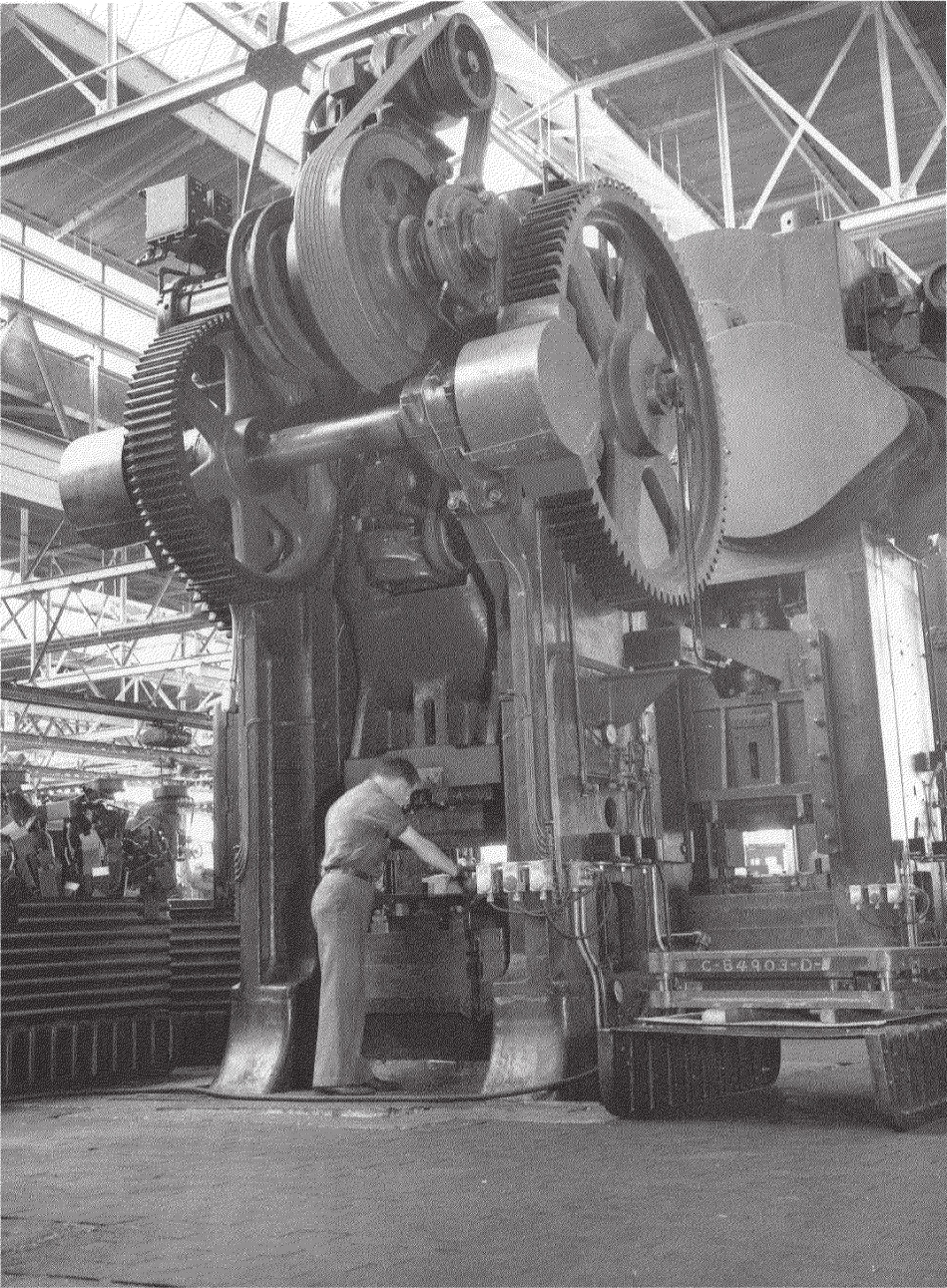

Figure 1: Industry

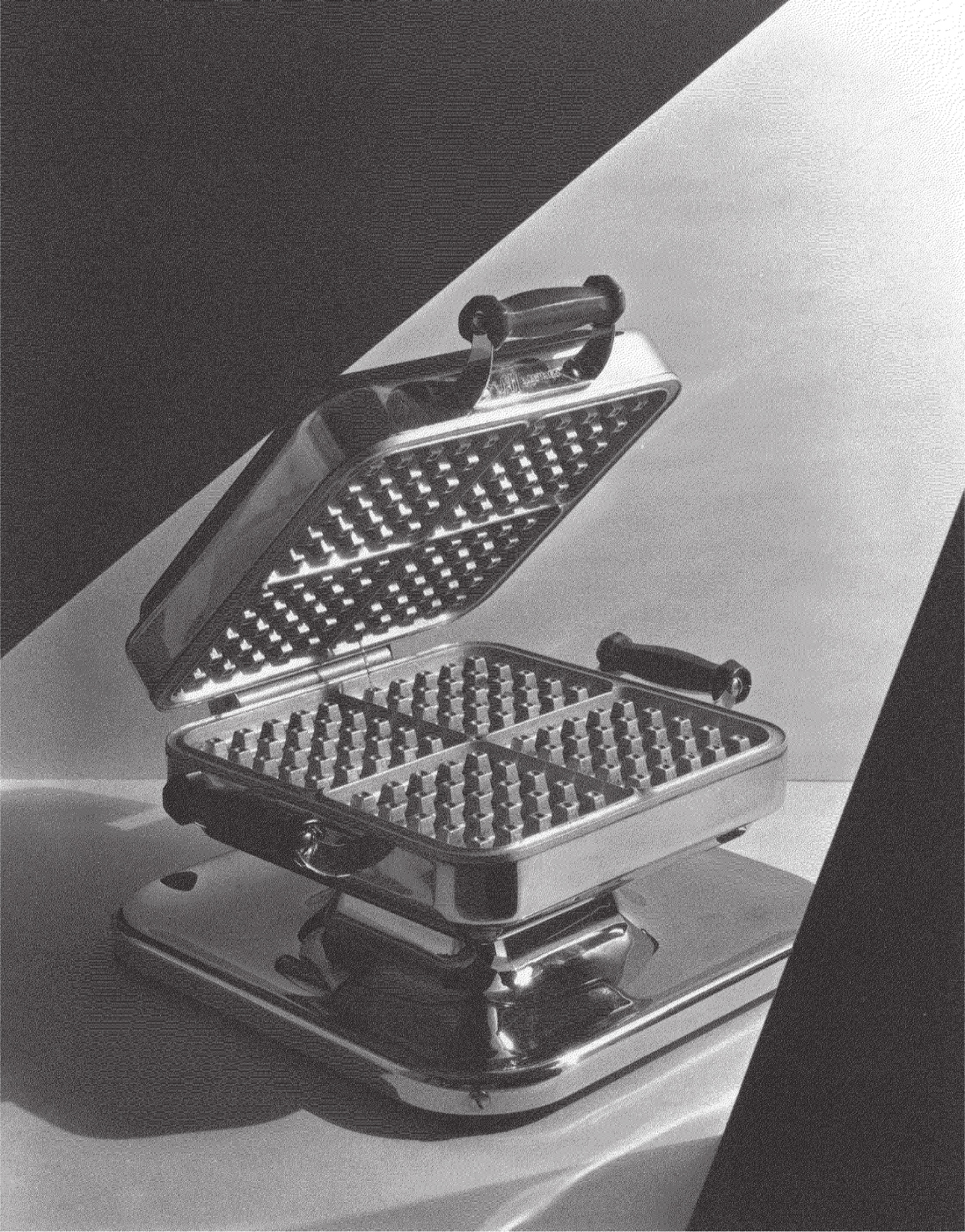

Figure 2: Potomac Electric Power Co. Electric Appliances. Waffle Iron

Figure 3: Bibel und Brille des Kanonikus

Figure 4: Chrysler Tank Arsenal

Figure 5: Compact Fluorescent

Figure 6: Conical Parachute

Figure 7: Cafetière Vesuviana

Figure 8: Nazca Lines Labyrinth

Figure 9: Anchor Chain for Brush Control

Figure 10: Old Water Wheel on Creek to North of Convent

Figure 11: A Sledge Hammer in the Hands of a Husky Iron Worker

Figure 12: Nature Meets Technology

Figure 13: Ted Was Right

Figure 14: Electric Oven. Setting Electric Oven II

Figure 15: All in All Just Another Hole in the Table

Figure 16: Train Wreck at Montparnasse Station

Figure 17: Footprint on Earth

Figure 18: Dew on Spider Web

Figure 19: Workers at Work

Figure 20: Space and Time

Figure 21: MMW

Figure 22: Power House Mechanic Working on Steam Pump

Figure 23: Miscellaneous Subjects. Telephone, Directory and Globe ← ix | x →

Figure 2: Potomac Electric Power Co. Electric Appliances. Waffle Iron

Source: Photography by Theodor Horydczak, ca. 1920, Library of Congress, Horydczak Collection: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/thc1995000607/PP/

| ix →

OUR DEBTS ARE MANY. Our families, first and foremost, deserve our sustained gratitude for, well, just about everything. Jennifer thanks Kenny Svenson, Pam Pels, Joe Pels, Linda Jantzen, Sue Slack, Laura Pagel, and a whole pack of dogs. Greg thanks Elise Wise, Catherine Wise, Brennen Wise; Donna and Tracy Wise; Sue and Carl Dimon; two dogs, and one cat.

The scholarly friends who have inspired and supported us constitute the most treasured part of the intellectual life. Thank you to Lawrence Grossberg, Stuart Hall, James Carey, Langdon Winner, Patty Sotirin, Kim Sawchuk, Sarah Sharma, Matt Soar, Jonathan Sterne, Anne Balsamo, Gil Rodman, Greg Seigworth, John Nguyet Erni, Mark Andrejevic, Steve Wiley, Ted Striphas, Charles Stivale, James Hay, Gordon Coonfield, Toby Miller, Andrew Herman, Ron Greene, Mehdi Semati, Meaghan Morris, Paul Bowman, Jody Berland, Jeremy Packer, Melissa Adams, Bryan Behrenhausen, Phaedra Pezzullo, Rob Poe, and Rob Spicer. Jennifer thanks the Department of Humanities at Michigan Technological University, especially her colleagues and graduate students in communication and cultural studies. Jennifer thanks Kette Thomas, Sue Collins, Stefka Hristova, Randy Harrison, Nate Carpenter, Mies Martin, Becky Soderna, and Wenjing Liu. She also thanks the Communication Department at North Carolina State University for support as a visiting professor. Greg thanks the faculty and staff of the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at Arizona State University, especially the folks in Communication Studies.

For enduring friendship outside the academy that brings balance and perspective to our lives, Jennifer thanks Melvi Grosnick, Terry Daulton, and Kathy and Chuck Wicker. Greg thanks all the Allens, Christians, Figueroas, Gelvins, Grells, Keiths, Marxs, Melchers, Villegas’es, Watsons, and Youngs, not to mention the wonderful folks at Dance Theater West (especially Frances Smith Cohen and Susan Sealove Silverman) for being our village. In addition, Greg would like to thank Sherrie and the good folks at White Cup Coffee for letting him camp out there for long stretches of time during the final editing of this book. ← ix | x →

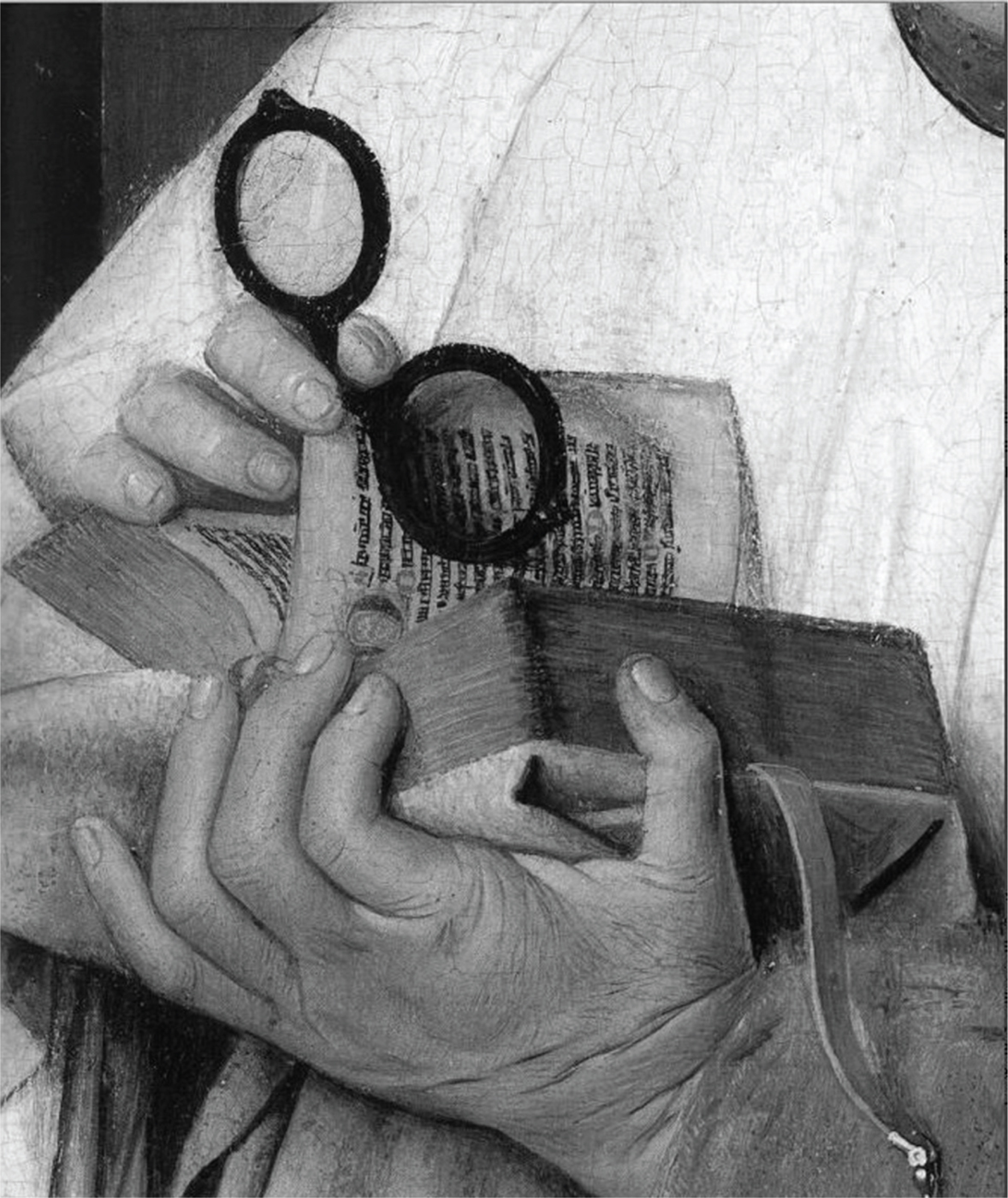

Figure 3: Madonna des Kanonikus Georg van der Paele, Detail: Bibel und Brille des Kanonikus

Source: Painting by Jan van Eyck, 1943, Wikimedia Commons, The Yorck Project, ZenodotVerlagsgesellschaftmbH wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jan_van_Eyck_059.jpg

| 1 →

TECHNOLOGICAL CULTURE HAS the power to shape attitudes and practices, but its power often goes unnoticed or is underappreciated. Every day it becomes increasingly important to understand and alter our relationship with technological culture. This is especially true when, as is so often the case, technological culture is shaping attitudes and practices that do not serve the interests of sustainability, equality, and peace. The scramble for non-renewable resources that both constitute and fuel technologies has contributed to strife, and sometimes war, of global proportions. New digital media technologies have enabled surveillance at a scale previously unimaginable. Inequitable delivery of health care is exacerbated, as expensive techniques of biotechnology are made unevenly available. Technological trash salts the earth and skies with pollution and provides toxic work for the most disadvantaged laborers on the planet. Global climate change, the fallout from all this technological madness, is widely denied in practice as the human imagination lives out the fantasy of unstoppable and infinite growth.

The stories that dominate education and the media are those that assert that technology is all good, all about progress, all about becoming superior kinds of human beings. That there is good is undeniable, but we have collectively lost perspective, lost the ability to critique the complexities of the technological culture in which we are immersed. Perhaps we haven’t lost it, because we may never really have had it. But now, with the consequences so seriously global, we need desperately to acquire this skill. We offer this book as a primer for that project.

Culture and Technology is a primer in three senses: 1) it is an introduction to the contributions of many generations of scholars and engaged individuals who provide helpful guidance for understanding technological culture, 2) it is an introduction to a coherent cultural studies approach to understanding and critiquing technological culture, and 3) it is a spark to light the fire of conscious and responsible engagement with technological culture.1 ← 1 | 2 →

This is a much revised and expanded second edition. A lot has happened in the world since the publication of the first edition in 2005, and we have responded accordingly. We, Greg and Jennifer, have also learned a lot from the students who have used the first edition and from readers from all over the world who have sent us feedback.

A new first chapter considers more explicitly how we use a cultural studies concept of culture. A new final chapter adds the concept of the conjuncture as a tool for analyzing technological culture, a change that results in a transformed conclusion. In addition to these new chapters, we have completely rewritten most of Part III, which lays out our approach to cultural studies as it applies to technological culture. Two glaring lacunae in the first edition have been corrected: the chapter on space has become space and time; the chapter on politics has become economics and politics. What were two chapters on identity have been reconsidered as one. And the chapter on definitions has been corrected to reflect its real intention: it is about meaning. Throughout the book, we have updated examples where newer ones were more useful for understanding contemporary experience. We have incorporated many new technological developments: new social media, cloud computing, biomedia, Edward Snowden’s revelations about NSA surveillance, the proliferation of e-waste, climate change, and so on. New research by remarkable scholars has been added, for example Sarah Sharma’s work on time and Natasha Dow Schüll’s work on addiction to machine gambling.

We do not profess to, or even attempt to, place before you contemporary technological culture in all its Technicolor intricacies. That isn’t possible. Instead there is a fourth sense in which we offer our work here as a primer. When painting a room that that is already painted in strong colors, you begin by applying a primer, a first thin coating of paint, after which you paint with a fully new color. The primer conditions the surface so that it is receptive to the new paint. This book is meant to be such an initial coating. It engages the brightly colored stories that currently color our understanding of technology and culture. It applies the primer, on top of which you are encouraged to contribute colorful new paint: to engage technological culture in your own circumstances, whatever and wherever they are, with theory, tools, and strategies meant to make the world a better place.

| 3 →

Figure 4: Chrysler Tank Arsenal

Source: Photography by Alfred T. Palmer, ca. 1940–1946, Library of Congress, Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photography Collection: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/oem2002009934/PP/ ← 3 | 4 →

Figure 5: Compact Fluorescent

Source: Photograph by Giligone, 2008, Wikimedia Commons

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Compact_Fluorescent-bw.jpg

| 5 →

The Power and Problem of Culture, The Power and Problem of Technology

WHAT YOU KNOW TO BE TRUE MATTERS. When you know something, you act in accordance: your beliefs and actions support what you know to be true, correct, and good; your beliefs and actions resist what you know to be false, wrong, and bad. Once you really know something, it is difficult to shake loose from the power of those convictions that guide thinking and behavior to learn something new or different. What is true for the individual is even more pronounced at the broader cultural level. When a culture accepts that something is true, its political structure, economic structure, institutions, laws, beliefs, everyday practices, and systems of reward and punishment will be shaped in that knowledge.

Unfortunately, what is widely accepted as true does not always serve us well. When everyone knew that the universe was geocentric, it made good sense to arrest Galileo Galilei and repress his heliocentric cosmology. It took generations to achieve general cultural acceptance of the knowledge that the earth revolves around the sun. But before heliocentrism became widely accepted, certain religious institutions maintained power over thought and practice, and scientific enterprise was marginalized and discredited. Sometimes, in spite of broad cultural consensus, it pays to struggle with complacent knowing and “worry” your way to better stories about how the world works.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 269

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433107757

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453914502

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454195832

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454195849

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1450-2

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2005 (September)

- Keywords

- history progress resistance debate influence contemporary theories

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG