Dynamics of International Advertising

Theoretical and Practical Perspectives

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- CHAPTER ONE Growth of International Business and Advertising

- HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

- SATURATED DOMESTIC MARKETS

- HIGHER PROFIT MARGINS IN FOREIGN MARKETS

- INCREASED FOREIGN COMPETITION IN DOMESTIC MARKETS

- THE TRADE DEFICIT

- THE EMERGENCE OF NEW MARKETS

- European Union

- Commonwealth of Independent States

- China

- WORLD TRADE

- GROWTH IN ADVERTISING EXPENDITURES WORLDWIDE

- TREND TOWARD INTERNATIONAL AGENCIES

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- CHAPTER TWO The International Marketing Mix

- GLOBALIZATION VERSUS LOCALIZATION OF THE MARKETING MIX

- PRODUCT

- PRODUCT STANDARDIZATION

- PRODUCT ADAPTATION

- NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

- COUNTRY-OF-ORIGIN EFFECT

- BRANDING AND TRADEMARK DECISIONS

- BRAND PIRACY

- PACKAGING AND LABELING DECISIONS

- PLACE

- Channels between Nations: Indirect Export

- Channels between Nations: Direct Export

- Channels between Nations: Manufacture Abroad

- Channels within Nations: Distribution to Consumers

- Channels within Nations: Wholesaling Abroad

- Channels within Nations: Retailing Abroad

- Distribution Standardization versus Specialization

- PRICE

- Pricing Objectives and Strategies

- Governmental Influences on Pricing

- Export Pricing

- Pricing and Manufacture Abroad

- PROMOTION

- Advertising

- Sales Promotion

- PUBLIC RELATIONS

- Personal Selling

- Direct Marketing

- Sponsorships

- Trade Fairs

- Product Integration

- Integrated Marketing Communications

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- CHAPTER THREE The International Marketing and Advertising Environment

- DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

- Market Size

- Population Growth

- Population Distribution

- ECONOMIC FACTORS

- Classification Systems

- Income

- Urbanization

- GEOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

- THE POLITICAL-LEGAL ENVIRONMENT

- Political-Legal Environment of the Home Country

- Political-Legal Environment of the Host Country

- Political Risk

- International Law

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- CHAPTER FOUR The Cultural Environment

- CONCEPT OF CULTURE

- Self-Reference Criterion and Ethnocentrism

- Subcultures

- CULTURE AND COMMUNICATION

- Verbal Communication

- Nonverbal Communication

- THE INFLUENCE OF CULTURE ON MARKETING AND ADVERTISING

- Religion, Morals, and Ethical Standards

- EXPRESSIONS OF CULTURE

- VALUES

- Internationally Based Frameworks for Examining Cultural Variation

- Hofstede’s Dimensions of Culture

- Power Distance

- Individualism versus Collectivism

- Masculinity versus Femininity

- Uncertainty Avoidance

- Long-Term/Short-Term Orientation

- The GLOBE Study

- INFLUENCE OF CULTURE ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

- Why Consumers Buy

- What Consumers Buy

- Who Makes Purchase Decisions

- How Much Consumers Buy

- CULTURAL UNIVERSALS

- TOOLS FOR UNDERSTANDING CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION

- Market Distance

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- CHAPTER FIVE Coordinating and Controlling International Advertising

- CENTRALIZED VERSUS DECENTRALIZED CONTROL OF INTERNATIONAL ADVERTISING

- Global Approach (Centralized Decision Process, Standardized Advertising Approach)

- Local Approach (Decentralized Decision Process, Differentiated Advertising Approach)

- Regcal Approach (Centralized Decision Process, Regional Approach)

- Glocal Approach (Decentralized Decision Process, Standardized Approach)

- AGENCY SELECTION

- Domestic and In-House Agencies

- International Agencies and Global Networks

- Foreign (Local) Agencies

- Agency Selection Criteria

- MARKETING AND ADVERTISING STRATEGY OPTIONS

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- CHAPTER SIX Creative Strategy and Execution

- STRATEGIC DECISIONS

- Globalization of Advertising

- Products Suitable for Globalized Advertising

- Localization of Advertising

- The Globalization-Localization Continuum

- EXECUTION DECISIONS

- Advertising Appeals

- Verbal Communication: Copy and Dialogue

- Music

- Nonverbal Communication: Visuals and Illustrations

- CREATIVITY IN THE INTERNATIONAL ARENA

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- CHAPTER SEVEN Advertising Media in the International Arena

- NATIONAL/LOCAL VERSUS INTERNATIONAL MEDIA

- NATIONAL/LOCAL MEDIA

- Media Availability

- Media Viability

- Media Coverage

- Media Cost

- Media Quality

- Role of Advertising in the Mass Media

- Media Spillover

- Local Broadcast Media

- Radio

- Local Print Media

- Other Local Media

- INTERNATIONAL MEDIA

- International Print Media

- International Broadcast Media

- International Media Data

- International Media-Buying Services

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- CHAPTER EIGHT Research in the International Arena

- STEPS IN RESEARCH DESIGN

- Problem Definition

- Determination of Information Sources

- Research Design

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis and Reporting

- SECONDARY DATA

- Problems with Secondary Data

- Domestic Sources of Secondary Data

- International Sources of Secondary Data

- PRIMARY DATA

- PRIMARY RESEARCH METHODS

- Observation

- Focus-Group Interviews and In-Depth Interviews

- Experimental Techniques

- Surveys

- RESEARCH RELATING TO MESSAGE DESIGN AND PLACEMENT

- TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES AND RESEARCH

- Control of International Research

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- CHAPTER NINE Advertising Regulatory Considerations in the International Arena

- INFLUENCES ON NATIONAL REGULATIONS

- Types of Products That May Be Advertised

- The Audiences That Advertisers May Address

- The Content or Creative Approach That May Be Employed

- The Media That Advertisers Are Permitted to Employ

- The Use of Advertising Materials Prepared Outside the Country

- The Use of Foreign Languages in Advertising and Marketing Materials

- The Use of Local versus International Advertising Agencies

- INTERNATIONAL AND REGIONAL REGULATION

- The United Nations

- World Trade Organization

- The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

- The European Union

- The Gulf Cooperation Council

- SELF-REGULATION

- The Trend toward Self-Regulation

- THE INTERNATIONAL CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

- Implications for International Advertisers

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- CHAPTER TEN Ethics and Beyond: Corporate Social Responsibility and Doing Business in the Global Marketplace

- BUSINESS ETHICS IN THE GLOBAL MARKETPLACE

- APPLYING ETHICS TO THE MARKETING MIX

- BEYOND ETHICS: CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

- COMMUNICATING CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY TO THE PUBLIC

- SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- Index

| ix →

My objective in preparing this second edition of Dynamics of International Advertising: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives was to reflect the dramatic changes that have impacted the field over the past 5 to 10 years. The current economic downturn has caused advertising budgets to shrink, agencies to lay off advertising professionals, and many consumers in developed and developing markets alike to tighten their belts. In response to the shifting demographics in more advanced countries, international advertisers are increasingly looking to developing markets for larger and more youthful consumer segments. New media forms are evolving—forms no one could have predicted when the first edition was published. And advertisers are increasingly being expected to behave in a socially responsible fashion—not only towards their customers, their employees, and the environment—but also to society at large. This new edition utilizes the best examples of contemporary advertising from around the globe to demonstrate how agencies are responding to these changes. The latest statistics are incorporated into each and every table. And new insights from academic research are highlighted.

This book introduces the reader to the challenges and difficulties of developing and implementing communications programs for foreign markets. Although advertising is the major focus, I recognize that an integrated marketing communications approach is critical to competing successfully in the international setting. In order to communicate effectively with audiences around the globe, marketers must coordinate not only advertising, direct marketing, sales promotions, personal selling, and public relations efforts, but all other aspects of the marketing mix as well. Therefore, the basics of international marketing are briefly reviewed in the first several chapters of this text. The remainder of the book then focuses on international advertising.

Significant changes are incorporated throughout the text, but I have kept the basic structure of the first edition. The text comprises a total of ten chapters. In Chapter 1, factors influencing the growth of international advertising are examined. Chapter 2 highlights the role that product, price, distribution, and promotion, play in selling abroad. Domestic advertising and international advertising differ not so much in concept as in environment; the international marketing and advertising environment is outlined in Chapter 3. Chapter 4 is devoted to developing a sensitivity to the various cultural factors that impact international marketing efforts. Chapter 5 addresses the coordination and control of international advertising. Chapter 6 deals with creative strategies and executions for foreign audiences. Chapters 7–9 explore media decisions in the global marketplace, international advertising research ← ix | x → and methods for obtaining the information necessary for making international advertising decisions, and, finally, regulatory considerations. Chapter 10 focuses on the social responsibility of international advertising agencies and multinational corporations in foreign markets.

Every attempt has been made to provide a balance of theoretical and practical perspectives. For example, the issues of centralization versus decentralization and standardization versus localization are addressed as they apply to the organization of international advertising programs, development and execution of creative strategy, media planning and buying, and advertising research. Readers will find that these are not black-and-white issues. Instead, they can be viewed as a continuum. Some marketing and advertising decisions can be centralized while others may not be. Similarly, depending on the product to be advertised and the audience to be targeted, some elements of the marketing and advertising mix may be standardized while others will be specialized.

First and foremost, Dynamics of International Advertising: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives is the ideal textbook for upper-division undergraduate and graduate students in specialized courses dealing with international advertising or marketing. It is also an effective supplemental text for introductory advertising, marketing, or mass communications courses seeking to expand coverage of the international dimension. The text should also prove useful to practitioners of international advertising, whether on the client side or within the advertising agency. Finally, researchers of international advertising and marketing will find it a valuable resource.

I am indebted to a number of individuals for the successful completion of this text. I am most grateful to the folks at Peter Lang Publishing. In particular, I’d like to acknowledge the editor of the first edition, Chris Myers. I wish that every author could have the kind of experience I had with Chris. He has the fine knack of making just about everything related to writing a textbook as painless and simple as it possibly can be. Many thanks to Mary Savigar, senior acquisitions editor, for encouraging the development of this second edition and for being such pleasure to work with. Bernadette Shade once again held my hand through the production process and oversaw the development of the eye-catching cover. On a personal note, this book—like my others—would not have been possible without the unconditional love and support of my husband, Juergen, and my daughter, Sophie. Both stood by me—as always—without complaint.

Barbara Mueller

| 1 →

Growth of International Business and Advertising

The keystone of our global economy is the multinational corporation. A growing number of corporations around the world have traversed geographical boundaries and become truly multinational in nature. As a result, consumers around the world write with Bic pens and wear Adidas running shoes, talk on Nokia cell phones and drive Toyota autos. Shoppers can stop in for a McDonald’s burger in Paris or Beijing, and German and Japanese citizens alike increasingly make their purchases with the American Express Card. And, for most other domestic firms, the question is no longer, Should we go international? Rather, the questions relate to when, how, and where the companies should enter the international marketplace. The growth and expansion of firms operating internationally have led to the growth in international advertising. U.S. agencies are increasingly looking abroad for clients. At the same time, foreign agencies are rapidly expanding around the globe, even taking control of some of the most prestigious U.S. agencies. The United States continues to both produce and consume the bulk of the world’s advertising. However, advertising’s global presence is evidenced by the location of major advertising markets. In rank order, the top global advertising markets are the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany, China, France, Italy, Spain, Brazil, and South Korea. And today, 8 of the top 10 world advertising organizations are headquartered outside the United States (Johnson 2009). This chapter outlines the growth of international business and advertising.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

There have been three waves of globalization since 1870. The first wave, between 1870 and 1914, was led by improvements in transport technology (from sailing ships to steam ships) and by lower tariff barriers. Further driving this first wave of modern globalization were rising production scale economies due to advancements in technology that outpaced the growth of the world economy. Product needs ← 1 | 2 → also became more homogenized in different countries as knowledge and industrialization diffused. Communication became easier with the telegraph and, later, the telephone. By the early 1900s, firms such as Ford Motor, Singer, Gillette, National Cash Register, Otis, and Western Electric already had commanding world market shares. Exports during this first wave nearly doubled to about 8 percent of world income (World Bank 2002, 326).

The trend to globalization slowed between 1914 and the late 1940s. These decades were marked by a world economic crisis as well as two world wars, which resulted in a period of strong nationalism. Countries attempted to salvage and strengthen their own economies by imposing high tariffs and quotas so as to keep out foreign goods and protect domestic employment. It was not until after the Second World War that the number of U.S. firms operating internationally again began to grow significantly.

The second wave of globalization was from 1945 to 1980. International tensions—whether in the form of cold war or open conflict—tend to discourage international marketing. However, during this period, the world was, for the most part, relatively peaceful. This, paired with the creation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) at the close of World War II, facilitated the growth of international trade and investment. Indeed, during this period, tariffs among the industrialized nations fell from about 40 percent in 1947 to roughly 5 percent by 1980. In 1950 U.S. foreign direct investment stood at $12 billion. By 1965 it had risen to $50 billion, and by the late 1970s to approximately $150 billion (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1995, 870).

The third wave of globalization has been from approximately 1980 to the present. Spurring this third wave has been further progress in transport (containerization and air freight) and communication technology (falling telecommunication costs associated with satellites, fiber-optic cable, cell telephones, and the Internet). Along with declining tariffs on manufactured goods (currently under 4 percent), many countries lowered barriers to foreign investment and improved their investment climates. After the September 11 attacks in the United States, some economists worried that the year 2001 would mark a reversal of the current era of globalization. Recession, U.S. security concerns, and resentment abroad seemed aligned against the forces that drove companies abroad in the 1990s in search of new markets. However, according to a PriceWaterhouseCoopers survey of 171 business executives at large U.S. multinationals, commitment to international expansion actually rose in the year after the September 11 attacks. Of those surveyed, 27 percent planned some sort of geographic expansion during the following year, up from 19 percent prior to the attacks (Hilsenrath 2002). And it appears that the same forces that drove globalization in the past might in fact be intensifying. A 2009 Fortune magazine survey reports that the top 500 multinational companies alone generated almost $25 trillion in sales in 2008. The United States led all countries, with 140 companies on the list (down from 153 the previous year); Japan ranked second (68 companies), and Germany third (38) (Fortune 2009). See Table 1.1 for ranking of the top 25 global firms.

In addition to these large corporations, thousands of smaller firms are engaging in international marketing. In the United States, smaller firms account for an amazing 97 percent of the companies involved in direct merchandise exporting. Indeed, smaller firms are grabbing an ever-growing share of U.S. exports. American businesses without international subsidiaries accounted for 46 percent of sales abroad in 2005—up from 38 percent in 1999, according to the Commerce Department (Schlisserman 2007). Smaller firms thus represent the largest pool for potential growth in export sales. Microbreweries provide an excellent example. With production normally limited to fewer than 15,000 barrels a year, microbreweries would seem more local than global players. But the microbrewery industry is going through a transition in which exports make sense. With more than 33 regional specialty breweries and ← 2 | 3 → 424 microbreweries in the United States, the field has become too competitive. As a result, several of the most successful “craft” brewers are among a growing number of smaller U.S. companies looking to foreign markets to expand sales. Brewers have had the greatest successes in Sweden, Italy, and, to a lesser extent, Great Britain.

Corporations look abroad for the very same reasons they seek to expand their markets at home. Where economies of scale are feasible, a large market is essential. However, if a single market is not large enough to absorb the entire output, a firm may look to other markets. If production equipment is not fully utilized in meeting the demands of one market, additional markets may be tapped. Seasonal fluctuations in demand in a particular market may also be evened out by sales in another. During economic downturns in one market, corporations may turn to new markets to absorb excess output. Firms may also find that a product’s life cycle can be extended if the product is introduced in different markets—products already considered obsolete by one group may well be sold successfully to another. In addition to the reasons noted, significant changes in the United States and around the globe have helped fuel this phenomenal growth in international business.

TABLE 1.1: World’s 25 Largest Corporations, 2009 (in U.S. million $)

Source: Fortune (2009), F1–F8. ← 3 | 4 →

SATURATED DOMESTIC MARKETS

As many markets reach saturation, firms look to foreign countries for new customers. Take the case of Starbucks. Starbucks began with 17 coffee shops in Seattle just two decades ago. Starbucks currently has over 11,500 stores in the United States alone. In Manhattan’s 24 square miles, Starbucks has 124 cafes, which translates into 1 for every 12,000 New Yorkers. In coffee-crazed Seattle, there is a Starbucks outlet for every 9,400 people, and the company considers that the upper limit of coffee-shop saturation. Indeed, the crowding of so many stores so close together has become a national joke, eliciting quips such as the headline in The Onion, a satirical publication: “A New Starbucks Opens in Restroom of Existing Starbucks” (Holmes 2002, 101). The company had been blessed with extraordinary growth in both store traffic and same-store sales until quite recently, when this trend reversed itself. While the reversal may be attributable to the U.S. economic slowdown, some investors fear that weak growth figures could indicate saturation in the U.S. market. Indeed, Starbucks closed 600 under-performing locations in 2006—apparently an admission that cannibalization seems to be a major problem, To keep up the growth, Starbucks realized it had no choice but to export its concept aggressively. In 1999, Starbucks had just 281 stores abroad. Today it has about 5,000 outlets in more than 40 countries—and it is still in the early stages of a plan of globalization. Starbucks expects to eventually increase the number of its stores worldwide to 40,000. Canada and the United Kingdom are currently Starbucks’s strongest markets abroad (some 69 percent of foreign revenues). However, India, Russia, and China represent key areas of focused future expansion.

HIGHER PROFIT MARGINS IN FOREIGN MARKETS

For the typical Fortune 500 company today, domestic revenues account for just 62.5 percent of total sales—a figure that is bound to shrink even further as globalization continues to advance. For an ever-growing number of firms, foreign revenues as a percentage of total revenues are well over 50 percent. Consider McDonald’s, which gets almost two-thirds of its revenue from overseas. For the quarter that ended September 30, 2007, it reported that sales at restaurants open at least 13 months grew 5.1 percent in the United States, 6.5 percent in Europe, and 11.4 percent in Asia/Pacific, the Middle East, and Africa (Pender 2007). General Motors Chairman Rick Wagoner estimates that foreign markets will soon account for 75 percent of the auto maker’s global sales, a testament to the booming growth in Asia, Russia, and far-Eastern Europe, as well as the fierce competition and market share erosion in the developed markets of the United States and Western Europe (Howes 2008). Examples of other firms that derive more than half of their revenues from abroad include: Hewlett-Packard (65 percent), Exxon Mobil (69 percent), Coca-Cola (72 percent), and Intel (79 percent). This trend toward higher profit margins in foreign markets is clearly not limited to U.S. firms. Nokia sells over 97 percent of its products outside the home market, and Toyota sells more vehicles in the United States than it does in Japan. Analysts figure that almost two-thirds of the company’s operating profits come from the United States. ← 4 | 5 →

INCREASED FOREIGN COMPETITION IN DOMESTIC MARKETS

Over the past decades, foreign products have played an increasingly significant role in the United States. Classic examples include the phonograph, color television, video- and audiotape recorders, telephone, and integrated circuit. Although all were invented in the United States, domestic producers accounted for only a small percentage of the U.S. market for most of these products—and an even smaller share of the world market. For example, in 1970, U.S. producers’ share of the domestic market for color televisions stood at nearly 90 percent. By 1990 it had dropped to little more than 10 percent. The decline in sales of United States-produced stereo components was even more serious—from 90 percent of domestic sales to little more than 1 percent during the same time span. Brand names such as Sony and Panasonic became household words for most American consumers.

Foreign companies continue to play a prominent part in the daily lives of Americans today, and domestic firms face competition in nearly every sector. While McDonald’s, Burger King, KFC, and Subway dominate the fast food scene, they face competition from every corner of the globe. Pollo Campero reigns from Guatemala. The chain has 52 U.S. locations to date, but has plans for 200 by 2014. It offers chicken so good KFC couldn’t beat it in Central America. Jollibee, from the Philippines, started out in California in 1998 and in 2009 added locations in New York and Las Vegas. The fast food restaurant serves everything from burgers with pineapple to spaghetti. Nando’s, a South African firm, serves up Afro-Portuguese chicken with a spicy “peri-peri” sauce. Nando’s has two locations in Washington, D.C. And British import Wagamama offers diners cheap ramen at three locations in Boston, with more coming to D.C. by 2010 (Demos 2009). When a U.S. consumer buys new tires, shops for the latest best-seller, or purchases a jar of mayonnaise, chances are increasingly good that the supplier will be a local subsidiary of a company based in Japan, Europe, or elsewhere outside the United States. For example, both Firestone Rubber and CBS Records were acquired by Japanese firms, and Macmillan Publishing and Pillsbury are owned by British firms (Shaughnessy and Lindquist 1993). Switzerland’s Nestlé and the Anglo-Dutch giant Unilever moved into the U.S. market to grow their businesses. Unilever set the pace, paying $20.3 billion for Bestfoods, whose brands include Hellmann’s Mayonnaise and Skippy Peanut Butter, as well as acquiring Slim-Fast, a diet-supplement firm, and Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream. Meanwhile, Nestlé acquired pet food manufacturer Ralston Purina, best known for its Purina Dog Chow brand. It was a logical move, as the pet food market is growing faster than Nestlé’s traditional, matured businesses—particularly in the United States, where animal owners are buying higher margin products that promise both dietary and health benefits for their pets (Bernard 2001). This “selling of America” has caused a good deal of concern among the business community as well as the general public. The United Kingdom is the biggest investor in the United States by far, followed by Japan, Germany, and Canada. Increased foreign competition on domestic soil is not unique to the United States, but rather is occurring both in developed countries and in emerging economies. Regarding developed markets, the United States remains the largest recipient of FDI, followed by the United Kingdom, France, Canada, and Germany.

Worldwide, foreign direct investment (FDI) fell in 2008 to an estimated $1.4 trillion, down from an all-time high of $1.8 trillion in 2007. This was due largely to the economic and financial crisis that dampened investors’ appetites to pour money abroad, including into the United States. Developed economies so far have been the hardest hit, as FDI was cut by an estimated one-third in 2008. Direct foreign investment flow to the United States slowed by just over 5 percent to $220 billion, while Japan captured 23 percent less FDI ($17.4 billion). FDI in Britain slumped from $224 billion in 2007 to an estimated $109.4 billion in 2008. Eastern and Central European economies suffered mixed ← 5 | 6 → fortunes with a slip in FDI for Poland and Hungary, but growth for the Czech Republic, Romania, and Russia. Developing countries managed to hold on to some growth in inward direct investment in 2008. China (up 10 percent, $82 billion) and India (up 60 percent, $36.7 billion) attracted more FDI in 2008. But Indonesia (minus 21 percent, $5.5 billion) Singapore (minus 57 percent, $10.3 billion), and Thailand (minus 4 percent, $9.2 billion) were the exceptions in Asia with declines. The United Nations Conference on Development (UNCTAD) suggested that poorer countries had been sheltered so far from the worst impact of the economic crisis and warned that they could suffer from an overall decline in foreign investment in the coming year (Agence France-Presse 2009). Overall, the trend continued in 2009, with FDI slipping to a little more than $1 trillion, as leading companies continued to cut costs and investments due to the poor economic outlook. Fortunately, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development sees a moderate recovery by the end of 2010 and expects the economy to gain momentum in 2011 (Schlein 2010).

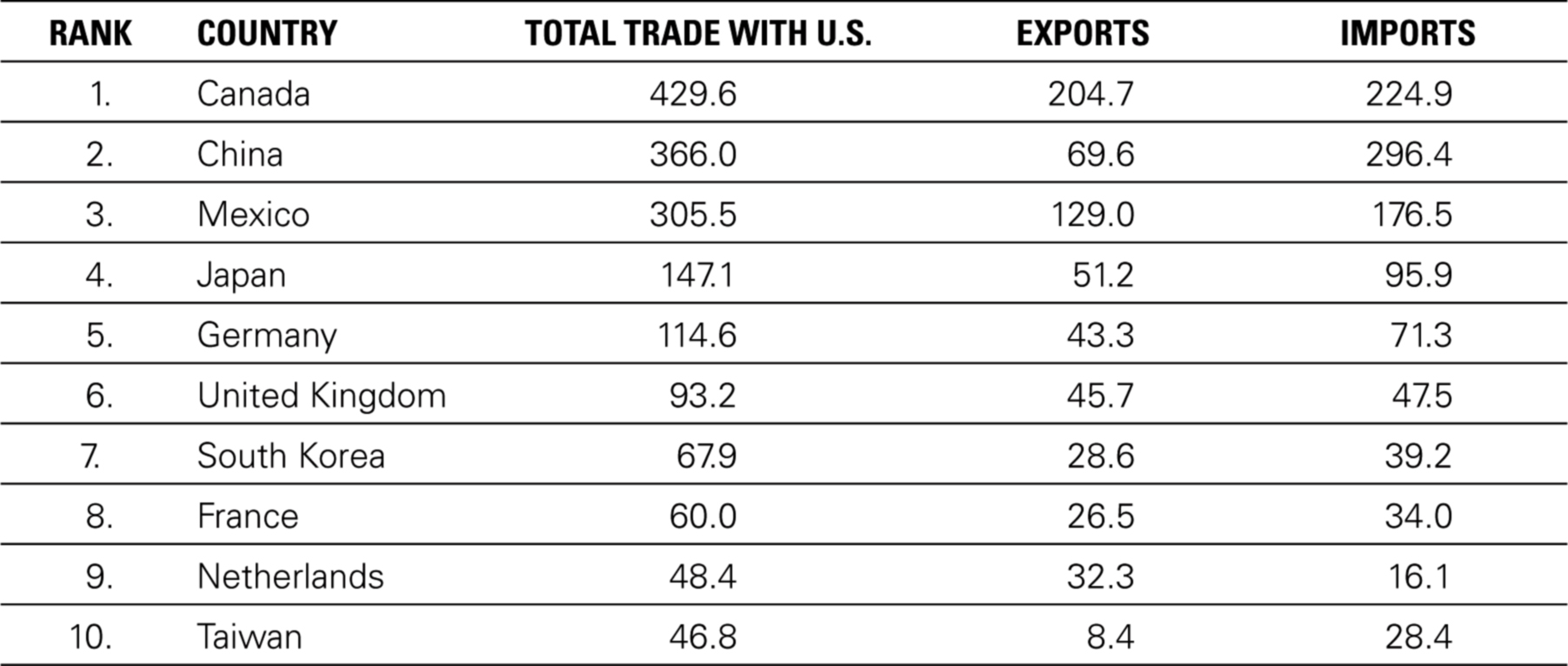

THE TRADE DEFICIT

Exports are considered a central contributor to economic growth and well-being for a country. In 2008, U.S. exports increased 12 percent to $1.84 trillion. However, imports climbed 7.4 percent to $2.52 trillion. The trade deficit is the shortfall between what a country sells abroad and what it imports. In 2006, the U.S. trade deficit was a whopping $765 billion and was referred to as the “Grand Canyon” of trade deficits. In 2007, for the first time since 2001, it dropped to $708.5 billion. It further decreased in 2008, to $677.1 billion. The long-term trends that pushed the trade deficit to record highs in the first place still persist, and much of the improvement in recent quarters reflects slower import growth and the fact of a weakening economy (Weller and Wheeler 2008). Indeed, in 2009, the U.S. trade deficit shrank to just $390.1 billion. But the net improvement came entirely on the import side, as America’s purchases of foreign goods and services shrank by more than 23 percent. Exports shrank, too—by just 15 percent. But because their fall-off was smaller, the deficit narrowed (Tonelson 2010). Amadeo (2010) provides an excellent analogy: “an on-going deficit is detrimental to the nation’s economy over the long term because it is financed with debt. In other words, the United States can buy more than it makes because the countries that it buys from are lending it the money. It is like a party where you’ve run out of money, but the pizza place is willing to keep sending you pizzas and put it on your tab. Of course, this can only go on as long as there are no other customers for the pizza and the pizza place can afford to loan you the money. One day the lending countries may decide to ask the United States to repay the debt. On that day, the party is over.” Table 1.2 presents U.S. trade with selected countries. Note that the United States exports much to its neighbors to the north and south.

THE EMERGENCE OF NEW MARKETS

European Union

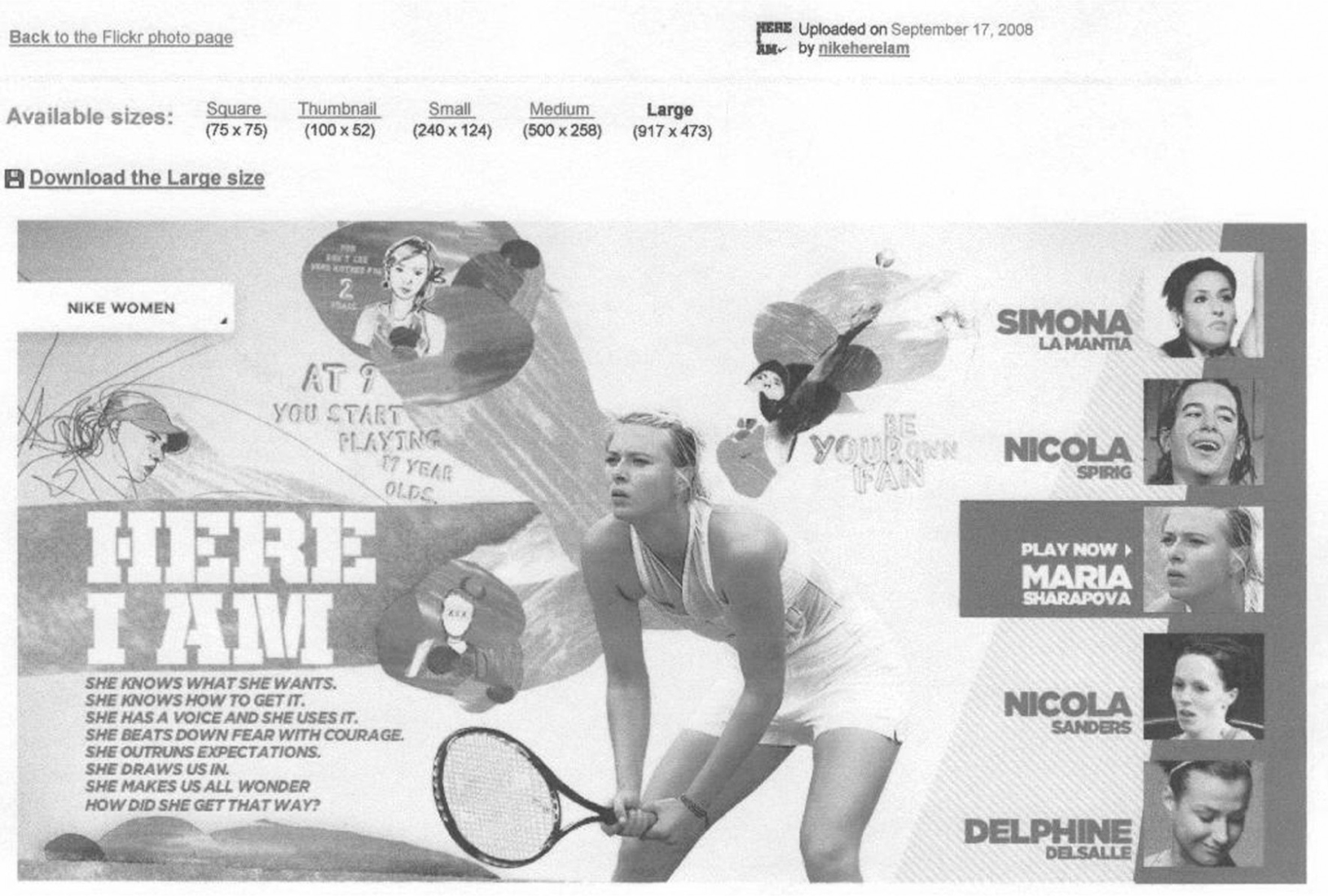

The emergence of new markets has stimulated interest in international business. On December 31, 1992, many physical, fiscal, and technical barriers to trade among the 12-nation European Union (EU) began to disappear, giving birth to something akin to the United States of Europe. The original “European 12” (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom) were joined by Sweden, Finland, and Austria ← 6 | 7 → in 1999, bringing the total population to 375 million with an average per capita gross domestic product of $23,500. And in 2004, 10 additional countries joined the union, making a new “Mega-Europe” of 25 states and more than 450 million consumers. The newcomers were Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Cyprus, and Malta. Most recently, in 2007, Bulgaria and Romania also joined the EU. In terms of GDP growth forecasts and average per capita income among the majority of member states, mega-Europe’s economy is on a par with that of the United States. Many companies have already approached Europe as a single market—rather than as a group of distinct countries—by realigning their product lines and developing strategies that can be employed throughout the EU. For example, Nike, which has been marketing its “Just do it” slogan since 1988, is trying out a new softer catchphrase on young European women: “Here I am.” Crafted by the Amsterdam office of the independent Wieden + Kennedy agency, the pan-European campaign includes five short animated web films about the life stories of five top European female athletes. One shows tennis player Maria Sharapova’s rise from a childhood in Siberia to the number-one-ranked player in the world. The spots highlight the criticism and negativity that Maria had to overcome. “You’re just another pretty face,” critics in the spot say. “You won’t be agile enough. You won’t stay on top for long.” At the end, the animated Sharapova morphs into the real Sharapova, who forms the “I” in “Here I am.” The aim of the campaign is to deliver the message that there is more to sports than getting fit or competing. It’s about building self-esteem. The idea for the slogan came out of research commissioned by Nike that found that university-aged women in Europe aren’t as competitive about sports as men. “To appeal to them, agency copywriters decided they needed a different slogan from the ‘Just do it’ message,” noted Mark Bernath, creative director for Nike at Wieden + Kennedy. “Here I am” promoted the personal benefit of exercise without being aggressive, he said (Patrick 2008). Nike executives liked the slogan because they thought it would be understood in English across Europe. Underscoring how marketers can use the Internet, particularly with younger consumers, Nike also paid for the spots to appear on Facebook, Bebo, and other social-networking sites popular with young women. In addition, Nike booked time for the ads on video screens in gyms and university student unions across Europe, including the U.K., France, Italy, Germany, and Russia. The campaign also included traditional television and print ads, on-line banners, and even a collection of athlete stories on the Nikewoman.com Web site (see Figure 1.1), as well as a gallery-worthy coffee table book featuring 22 young international female athletes.

TABLE 1.2: U.S. Trade with Selected Countries 2009 (in U.S. million $)

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census (2010). ← 7 | 8 →

Figure 1.1: Ad from Nike’s “Here I Am” campaign.

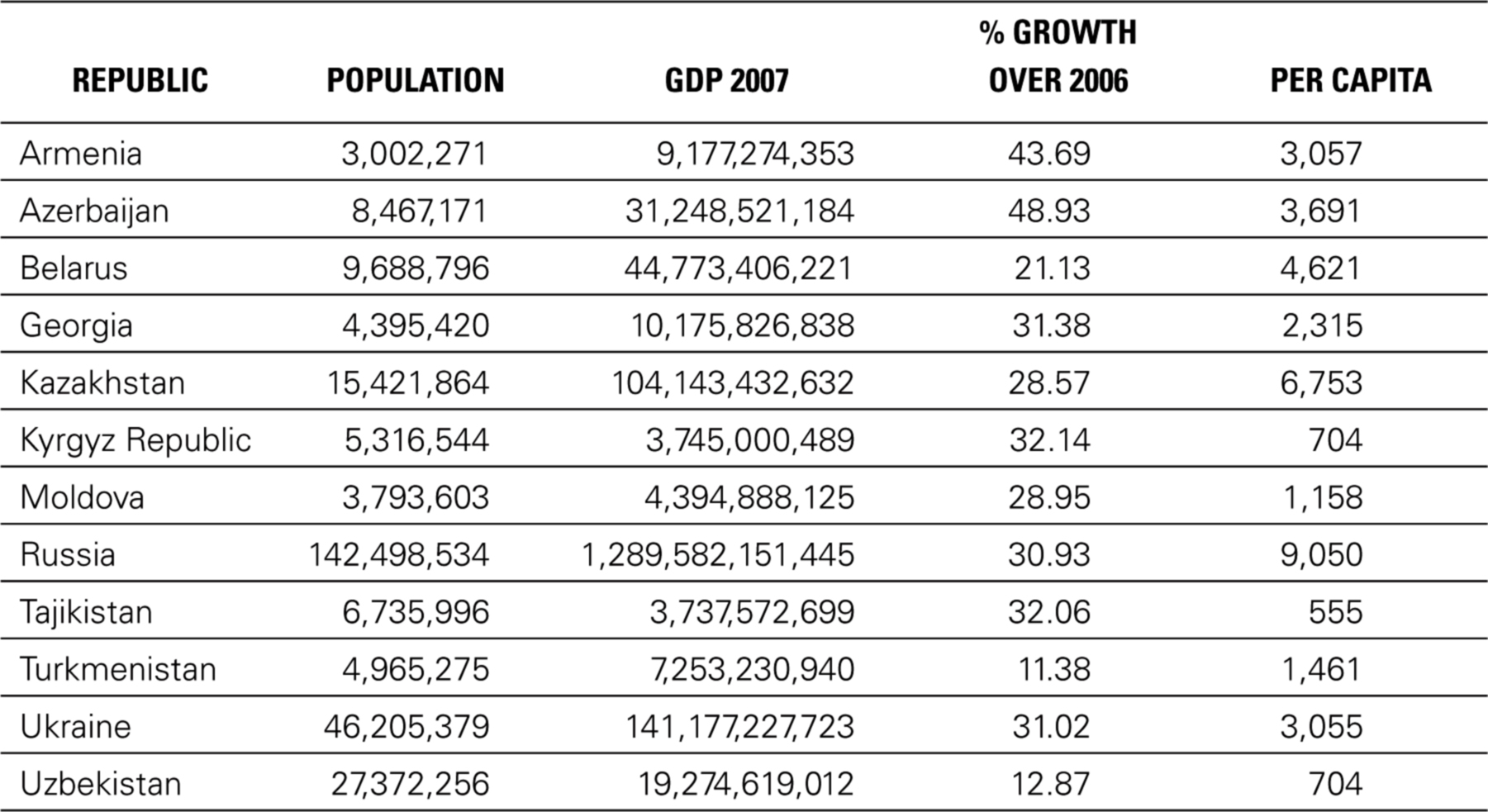

Commonwealth of Independent States

With the failed coup of August 1991, the subsequent resignation of President Mikhail Gorbachev, and the relegation of the former Soviet Union to official oblivion, trade and investment opportunities in the newly formed Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) increased dramatically. Corporations around the globe eyed the CIS, with its population of over 275 million, as the next marketing frontier. The CIS was officially formed in December 1991 by Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine, when the leaders of the three countries signed a Creation Agreement on the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the creation of the CIS as a successor entity to the USSR. On 21 December 1991, eight additional former Soviet Republics (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) joined the CIS. Georgia joined two years later, bringing the total number of participating countries to 12. The three Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—decided not to join, preferring to pursue membership in the European Union. The Creation Agreement remained the primary constituent document of the CIS until January 1993, when the CIS Charter was adopted. This charter formalized the concept of membership in that it defined a member country as one that ratifies the CIS Charter. It is of interest to note that Turkmenistan has not ratified the charter and changed its standing to associate member in 2005, and Ukraine, one of the three founding countries, ← 8 | 9 → has never ratified the CIS Charter and is thus not legally a member. Further, following the South Ossetian war in 2008, Georgia’s President Saakashvili announced that his country would leave the CIS, and the Georgian Parliament voted unanimously to withdraw from the regional organization. Georgia’s withdrawal became effective on 17 August 2009. The population of the CIS is a heterogeneous one, and while the official language is Russian, there are more than 200 languages and dialects (at least 18 with more than 1 million speakers). Table 1.3 presents basic demographic information for the CIS. Note that Russia, with its 142 million consumers, is by far the largest of the republics, and also boasts the wealthiest consumers in terms of per capita income.

TABLE 1.3: Demographic Profile of the Commonwealth of Independent States, 2008

Source: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/snaama/selectionbasicFast.asp.

Details

- Pages

- X, 368

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453914953

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454199991

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454200000

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433103841

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1495-3

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2004 (June)

- Keywords

- add marketing economy International Culture Communication Marketing Advertising cultural norms political environments social contexts marketing mix

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG