Italian Yearbook of Human Rights 2014

Summary

The 2014 Yearbook surveys the activities of the relevant national and local Italian actors, including governmental bodies, civil society organisations and universities. It also presents reports and recommendations that have been addressed to Italy by international monitoring bodies within the framework of the United Nations, the Council of Europe and the European Union. Finally, the Yearbook provides a selection of international and national case-law that casts light on Italy’s position vis-à-vis internationally recognised human rights.

«Italy and human rights in 2013: the challenges of social justice and the right to peace» is the focus of the introductory section of the Yearbook. With a view on the second Universal Periodic Review of Italy before the Human Rights Council, the Italian Agenda of Human Rights 2014, intended to be an orientation tool with regards to immediate and longterm measures that should be taken to ensure human rights for all in the Country, is integrated by an analysis of the status of implementation of the recommendations made to Italy during the first Universal Periodic Review (2010).

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Italy and Human Rights in 2013: the Challenges of Social Justice and the Right to Peace

- I. Regulatory and Infrastructural Human Rights Situation

- II. Implementation of International Obligations and Commitments: Implementation of ECtHR Case-law

- III. Adoption and Implementation of Policies

- IV. Structure of the 2014 Yearbook

- Upr: Towards the Second Cycle of the Universal Periodic Review

- Italian Agenda of Human Rights 2014

- Part I. Implementation of International Human Rights Law in Italy

- International Human Rights Law

- I. Legal Instruments of the United Nations

- II. Legal Instruments on Disarmament and Non-proliferation

- III. Legal Instruments of the Council of Europe

- IV. European Union Law

- Italian Law

- I. The Constitution of the Italian Republic

- II. National Legislation

- III. Municipal, Provincial and Regional Statutes

- IV. Regional Laws

- Part II. The Human Rights Infrastructure in Italy

- National Bodies with Jurisdiction over Human Rights

- I. Parliamentary Bodies

- II. Prime Minister’s Office (Presidency)

- III. Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- IV. Ministry of Labour and Social Policies

- V. Ministry of Justice

- VI. Judicial Authorities

- VII. National Economy and Labour Council (CNEL)

- VIII. Independent Authorities

- IX. Non-governmental Organisations

- X. Human Rights Teaching and Research in Italian Universities

- Sub-national Human Rights Structures

- I. Peace Human Rights Offices in Municipalities, Provinces and Regions

- II. Ombudspersons in the Italian Regions and Provinces

- III. National Coordinating Body of Ombudspersons

- IV. Network of Ombudspersons for Children and Adolescents

- V. National Coordinating Network of Ombudspersons for the Rights of Detainees

- VI. National Coordinating Body of Local Authorities for Peace and Human Rights

- VII. Archives and Other Regional Projects for the Promotion of a Culture of Peace and Human Rights

- Region of Veneto

- I. Regional Department for International Relations

- II. Committee for Human Rights and the Culture of Peace

- III. Committee for Development Cooperation

- IV. Regional Archive “Pace Diritti Umani – Peace Human Rights”

- V. Venice for Peace Research Foundation

- VI. Ombudsperson for Children and Adolescents

- VII. Ombudsperson

- VIII. Regional Commission for Equal Opportunities between Men and Women

- IX. Regional Observatory on Social Policies

- X. Regional Observatory on Immigration

- Part III. Italy in Dialogue with International Human Rights Institutions

- The United Nations System

- I. General Assembly

- II. Human Rights Council

- III. High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

- IV. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- V. Human Rights Treaty Bodies

- VI. Specialised United Nations Agencies, Programmes and Funds

- VII. International Organisations with Permanent Observer Status at the General Assembly

- Council of Europe

- I. Parliamentary Assembly

- II. Committee of Ministers

- III. European Court of Human Rights

- IV. Committee for the Prevention of Torture

- V. European Committee of Social Rights

- VI. Commissioner for Human Rights

- VII. European Commission against Racism and Intolerance

- VIII. Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

- IX. European Commission for Democracy through Law

- X. Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings

- XI. Group of States against Corruption2

- European Union

- I. European Parliament

- II. European Commission

- III. Council of the European Union

- IV. Court of Justice of the European Union

- V. European External Action Service

- VI. Special Representative for Human Rights

- VII. Fundamental Rights Agency

- VIII. European Ombudsman

- IX. European Data Protection Supervisor

- Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe

- I. Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR)

- II. High Commissioner on National Minorities

- III. OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

- IV. Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings

- International Humanitarian and Criminal Law

- I. Adapting to International Humanitarian and Criminal Law

- II. The Italian Contribution to Peace-keeping and Other International Missions

- Part IV. National and International Case-Law

- Human Rights in Italian Case-law

- I. Dignity of the Person and Principles of Biolaw

- II. Asylum and International Protection

- III. Discrimination

- IV. Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- V. Social Rights

- VI. Laws Affecting Individual Rights with Retroactive Effect

- VII. Immigration

- VIII. Right to Privacy, Right to Property

- IX. Children’s Rights

- X. Fair Trial and Pinto Law

- XI. Torture, Prison Conditions, Rights of Detainees

- XII. Criminal Matters

- Italy in the Case-law of the European Court of Human Rights

- I. Pilot Judgments and Related Cases

- II. Other Cases Decided by the Chambers and Committees of the Court

- Italy in the Case-law of the Court of Justice of the European Union

- Legal Approach to the Chairperson-Rapporteur’s Draft Declaration in Light of the Current Debate on the Right of Peoples to Peace

- Index

- Italian Case-law

- Research and Editorial Committee

- Series index

← 14 | 15 → Italy and Human Rights in 2013: the Challenges of Social Justice and the Right to Peace

In autumn 2014, the United Nations Human Rights Council will conduct its second Universal Periodic Review of Italy, primarily in order to ascertain the degree of compliance reached in Italy following the recommendations made during the first round of reviews. The 2014 Yearbook aims to provide empirical evidence which should prove useful, in addition to supporting the preparation for this operation, in enacting a comprehensive human rights system in Italy which is compliant with the principles and guidelines repeatedly recommended by the United Nations and the Council of Europe. The most important step is to establish the National Human Rights Commission as an independent body for the protection and promotion of fundamental rights. Italy made a commitment to this when putting its own candidature forward for a second mandate as a member of the Human Rights Council. It should be noted that, in the last years, there have been a series of bills in re, yet none of them have come to fruition in any way. Meanwhile, the Inter-ministerial Committee for Human Rights at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been reconstituted, and this body is charged with operating in the area of governmental functions.

The 2014 Yearbook, like the previous edition, cannot but report the protracted state of great suffering for rights in Italy, particularly economic and social rights, starting from the right to work and to social security: the general unemployment rate is 13%, and youth unemployment stands at 42.3% (ISTAT data, March 2014).

The woes of social and economic rights are also spreading to the field of civil and political rights, creating difficulties for the very practice of democracy and fanning the fires of corporate egoism, inter-generational conflict, racist sentiment and anachronistic nationalism, as well as heightening the lack of confidence in public institutions at the national, European and international level. Social cohesion and even territorial cohesion are at risk. It is well to recall here just how peremptory are the provisions of the second paragraph of article 20 of the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political rights, ratified by Italy in 1977: “Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law”.

Again, in the previous editions of the Yearbook, emphasis was put on the fact that, in virtue of the principle of the interdependence and indivisibility of all human rights – economic, social, civil, political and ← 15 | 16 → cultural – policies which comply with the requirements of social justice are for all States an obligation, not an optional extra; it is reiterated that the social state and the rule of law are two indissociable infrastructural attributes of sustainable statehood. For the Member States of the European Union, this obligation is specifically mentioned in the Treaty of Lisbon, where it establishes that the Union shall work for sustainable development, based, specifically, on “a highly competitive social market economy, aiming at full employment and social progress” (article 3(3)). It should also be remembered that the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights includes civil and political rights as well as economic, social and cultural rights, and that the Lisbon Treaty itself makes specific reference, in its Preamble, to the 1961 European Social Charter and the 1989 Community Charter of the Fundamental Social Rights of Workers.

The 2013 Yearbook quoted the warning from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navanethem Pillay, “the right to work is a fundamental human right which is inseparable from human dignity”, to make the strongest possible statement that unemployment prevents the full realisation of the person, takes away the sense of ethics of one’s “vocation”, restricts horizons of freedom and the promotion of human dignity, and undermines education and training processes at their roots. It is useful to repeat, opportune et inopportune, that a Civilisation of Law comes to fulfilment when, in recognising all the rights relating to human dignity, it meets and espouses the Civilisation of Labour, obliging Governments and the other actors in economic processes to face market challenges with a compass of fundamental rights. These are a series of practical truths – as Jacques Maritain defined them – which predicate their true incarnation on individual and social behaviours, on public policies, on positive measures and on comprehensive investments in education. In other words, they constitute a “political agenda” which feeds into good governance processes in the multi-level glocal space which stretches from the town hall to the United Nations.

And so it is necessary, once and for all, to go beyond the limits and determinisms of the pervasive and malignant sub-culture which distinguishes, but in actual fact separates, the subject of fundamental rights from that of political action and decision-making, that is, cutting off the right from the corresponding obligation to implement it.

It should be strongly emphasised here that human rights, in addition to being “the parents of Law”, as Amartya Sen typically argued, are political agenda, the alpha and omega of good governance.

The imperative of good governance is, of course, incumbent on inter-governmental and supranational organisations as well as on States, as they promote international human rights law and monitor its application by all States. However, the issue of monitoring and possibly applying penalties ← 16 | 17 → for the violation of rules is not the sole function of these international institutions. Indeed, they determine and implement veritable Government programmes, which affect a broad range of vitally important sectors. And so, like States, they too are bound to the respect of human rights, the rule of law and democratic principles, setting a good example in pursuing the objectives set by the overarching human development and human security strategies. For this to happen, it is necessary that the States making up the inter-governmental organisations respect the statutes of the same, and hence fulfil their obligation to make them function effectively, to provide them with the necessary human and financial resources and allow their structure and functioning to be made more democratic. As concerns Italy’s responsibilities in this area, article 11 of the Constitution clearly states that: “Italy rejects war as an instrument of aggression against the freedom of other peoples and as a means for the settlement of international disputes. Italy agrees, on conditions of equality with other States, to the limitations of sovereignty that may be necessary to a world order ensuring peace and justice among the Nations. Italy promotes and encourages international organisations furthering such ends”.

The dynamics of human rights must be considered not only in a vision of the plurality of its contents in substance, but also in the light of a territorial and functional context which, as previously mentioned, has a glocal dimension, and wherein the “responsibility to protect” human rights, that is, the commitment to guarantee them, must necessarily be shared between all institutions operating at the various levels from towns up to the highest supranational bodies.

In this respect, it is well to refer back to article 1 of the 1999 United Nations Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms: “Everyone has the right, individually and in association with others, to promote and to strive for the protection and realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms at the national and international levels (italics added). So there are no borders limiting the actions of human rights defenders, be they individuals, associations or local government bodies, the latter in their capacity as “organs of society”. One should note that, pursuant to the Italian Constitution, Municipalities and Regions are part of the Republic, not of the State.

The reference to borderless space for the realisation of human rights calls to mind the model of world order the DNA of which is found in the United Nations Charter and in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is the order of positive peace as defined in article 28 of the Declaration: “Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized”.

← 17 | 18 → It is essential to keep this model in the spotlight, to avoid being paralysed in the situation of liquidity – synonym of precariousness and insecurity – evocatively diagnosed by Zygmunt Baumann with reference to the human condition in the globalised world.

One will realise that not everything is “liquid”. If one knows how to look for it, there is ample empirical evidence of the existence of “solids”, identifiable in the genuine presence of elements of good governance of an infrastructural nature. First of all comes the “normative solid”, constituted specifically by the universal code of human rights and the relative machinery to implement them. Then there is the “organisational solid”, made up of the legitimate international institutions operating at the dual regional and universal level: from the United Nations Organisation to the European Union, from UNESCO and the ILO to the African Union, ASEAN, and the OAS, etc.

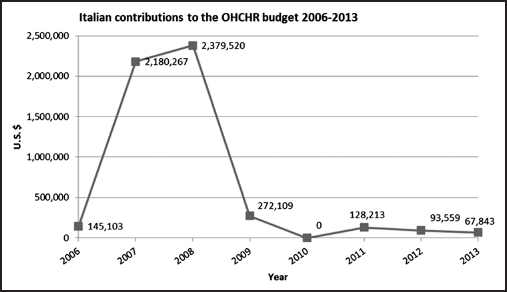

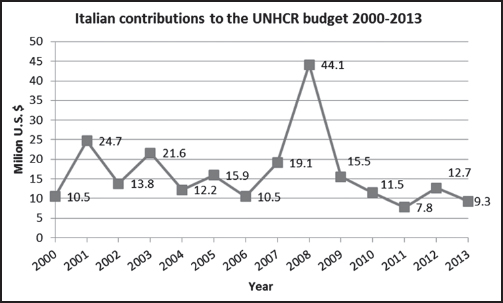

These organisations are “common houses” which exist in order to be enjoyed by all members of the human family, and for the proper running of which the member States are responsible. Significantly, the genuine commitment of Governments is measured according to their active participation in the functioning of these organs, but also according to the funds they allocate as their voluntary contributions to the organisations they belong to. In 2013, Italy’s contribution to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights was approximately $ 68,000 (ranking it 42nd as a donor), representing a decrease of about $ 25,000 compared to the previous year (when it was in 40th place). As concerns the budget of the High Commissioner for Refugees, in 2013, Italy contributed $ 9.3 million, a decrease of about $ 3.4 million dollars compared to the previous year.

Source: OHCHR, United Nations Human Rights Appeal 2014.

In 2013, Italy’s participation in the work of the United Nations Human Rights Council was particularly distinguished by the fact that over half of the 95 resolutions adopted by the Council saw Italy’s direct participation (as a sponsor) or diplomatic support (as a co-sponsor), and that Italy’s position was “winning” in 15 of the 28 votes cast. It is pointed out that two of the four “thematic” resolutions promoted by Italy refer to the contributions of national parliaments to the completion of the Universal Periodic Review and to the world programme for human rights education respectively.

In the education field, it should be noted that Italy was an active member of the platform of States which worked for the drafting and approval in 2011 of the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training. There is now an expectation that the Italian Government, on the strength of its active role at the world level, should promptly adopt comprehensive plans to develop education in human rights, peace and democratic citizenship for schools at all levels. It is within this area that efforts must finally be made to recapitulate the various rivulets of sectorial education (on sustainable development, citizenship, legality, environment, etc.) around the human rights paradigm. The guidelines for this operation can be found in three fundamental international documents: the Resolution and Programme of Action on a Culture of Peace and human rights; the Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training, both from the United Nations, and the Council of Europe Charter on Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights Education. In Italy, the Government is expected to feel spurred on in this direction by ← 19 | 20 → the example set by the good number of universities which continue to offer teaching and develop research in the specific field of human rights. Indeed, in 2013 there were 109 units specifically devoted to human rights, taught in 38 different universities. Over half of these units are included in degree courses in the area of politics and social sciences (numbering 61, or 56%), whereas a third are in the Law area (36 units, or 33%); 9 are in the areas of history, philosophy, pedagogy and psychology (8%) and 3 in the area of economics and statistics (3%). Top of the list of universities is the University of Padua with 20 units, followed by the University of Turin with 8. The strong presence of courses in the political and social sciences area is proof that the prevalent approach is decidedly policy and action-oriented, in line with the natural theoretical approach to the subject: or the axio-practical approach.

Since 2012, an inter-governmental working group tasked with drafting a Declaration on the Right to peace has been operating within the United Nations Human Rights Council. From the outset, carrying out this mandate has proven fraught with difficulties because certain States declared their a priori rejection of the draft document being debated. One of their objections is that since current international law does not include a specific right to peace, such a right cannot be introduced by a Declaration. Another objection is that if peace were to be recognised as a fundamental right of the person and of peoples, all formally recognised human rights would be weakened as a consequence. These are clearly spurious arguments. A number of non-governmental organisations with consultative status at ECOSOC are taking an active part in the work of the aforementioned inter-governmental working group and are, as is to be expected, aligned in favour of the initiative. In Italy, the ongoing debate in Geneva has attracted the attention of a number of Municipal Councils, which have included the so-called “peace human rights norm” in their respective Statutes; this norm makes reference to the Italian Constitution and international human rights law to recognise peace as a fundamental right of the person and of peoples. Following a proposal from, and with the support of, the Human Rights Centre of the University of Padua, the Italian Coordination of Local Authorities for Peace and Human Rights asked municipal (and provincial) councils to approve a detailed petitionary motion supporting the initiative of the Human Rights Council. As the current edition of the Yearbook is going to print, there are news that about a hundred Municipal Councils large and small, from the Alps in the north to the southernmost tip of Italy, from east to west, in Sicily and in Sardinia, have approved the motion and are sending a delegation to deliver a copy of each to the Chairperson-Rapporteur of the Working Group, Ambassador Christian Guillermet Fernandez (Costa Rica), to the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, and to the Head of the ← 20 | 21 → Italian Mission, Ambassador Maurizio Enrico Serra. The Human Rights Centre of the University of Padua accompanied this virtuous mobilisation of local administrations with a special edition of its review “Pace diritti umani/Peace human rights” entirely devoted to “The right to peace” (Marsilio Editori, 2013, 240 pages), published with the collaboration of the Permanent Mission of Costa Rica to the United Nations (Geneva), specifically from the aforementioned Ambassador Guillermet and his legal advisor, David Fernàndez Puyana. Their Mission also distributed the magazine to the representatives of Human Rights Council member States and in other areas of the United Nations.

Details

- Pages

- 436

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035264821

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035299397

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035299403

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9782875742179

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0352-6482-1

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (December)

- Keywords

- social justice peace legislation

- Published

- Bruxelles, Bern, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 436 pp., num. tables