Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

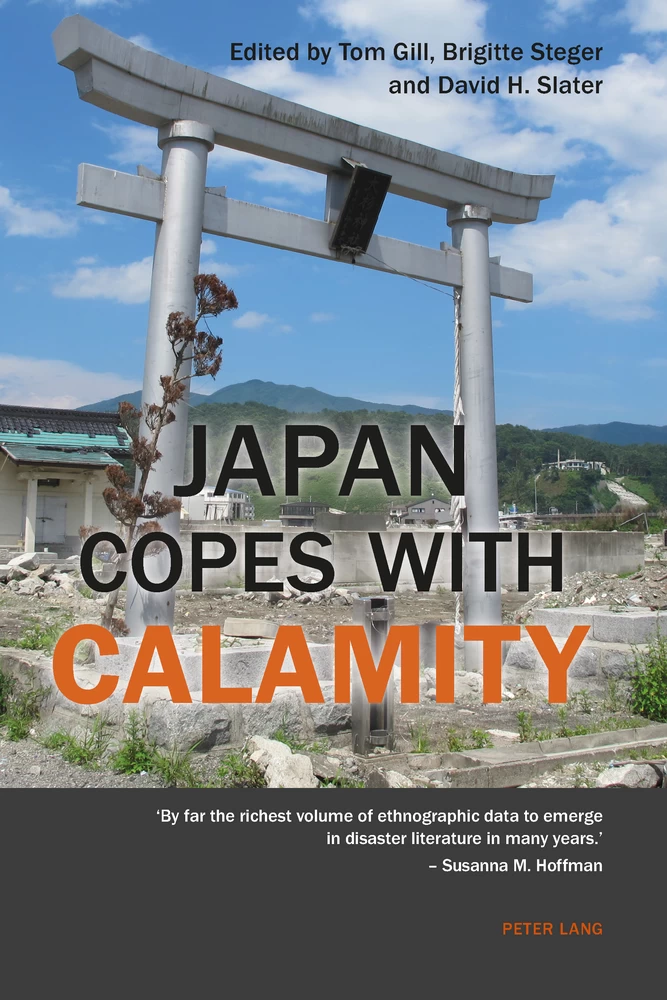

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface and Acknowledgements to the First Edition

- Introduction

- The 3.11 Disasters

- Urgent Ethnography

- Part 1: Coping with Life after the Tsunami

- Solidarity and Distinction through Practices of Cleanliness in Tsunami Evacuation Shelters in Yamada, Iwate Prefecture

- Adapting Religious Practice in Response to Disaster in Iwate Prefecture

- No Homes, No Boats, No Rafts: Miyagi Coastal People in the Aftermath of Disaster

- Part 2: Coping with Life after the Nuclear Disaster

- Them versus Us: Japanese and International Reporting of the Fukushima Nuclear Crisis

- The Construction of Risk and the Resilience of Fukushima in the Aftermath of the Nuclear Power Plant Accident

- Mother Courage: Women as Activists between a Passive Populace and a Paralyzed Government

- This Spoiled Soil: Place, People and Community in an Irradiated Village in Fukushima Prefecture

- Part 3: Insider/Outsider Encounters

- Youth for 3.11 and the Challenge of Dispatching Young Urban Volunteers to North-eastern Japan

- Moralities of Volunteer Aid: The Permutations of Gifts and their Reciprocals

- Epilogue

- Still Missing …

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

← viii | ix → Preface to the Second Edition

We are very happy to see this new edition of Japan Copes with Calamity published. The first edition has already been reprinted, as has the Japanese edition, which was also published in 2013. The demand for the book reflects the continuing lack of closely observed ethnographic studies of the 3.11 disasters but the enduring interest in the human aspect of the disasters. The book has received a warm response from informants in the disaster zone and many of them have told us they are glad that their voices have been heard.

We would like to take this opportunity to offer a brief update on post-disaster Japan as seen from a standpoint eighteen months on from the original publication.

‘Is everything back to normal now?’ This is what we are asked frequently, when we return from our visits to Tohoku. Coming from people living well away from the disaster zone, it is an understandable question. Three or four years after the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disasters, life outside the zone has moved on. The flood of news items about the disaster has slowed to a trickle. The government of prime minister Abe Shinzo has engineered a temporary economic recovery under the name of ‘Abenomics’, a fashionable word that really means using the time-honoured pump-priming methods of the Liberal Democratic Party: injecting trillions of yen1 of borrowed money into the economy, much of it spent on public works.

Occasionally, people are reminded of the Fukushima accident when they hear of another anti-nuclear demonstration and when they hear that the leaks of contaminated water were actually much bigger and more damaging than they had been told, but generally they prefer to believe in the reassurance of the government that the Fukushima plant, the post-disaster recovery process, the economy and things in general are under control.

← ix | x → Along the Sanriku coast of Tohoku, the situation is quite different. Clearing flat areas on mountains and securing land to provide safe building space has only just started in some areas. Giant cranes and Caterpillar tractors are everywhere. The huge piles of wreckage have been sorted and moved away for recycling and a few former beaches have been prepared for holiday makers. However, locals still feel uncomfortable to relax in the bay, where they know that tons of rubbish was washed away and many people were drowned, many of them never discovered.

In Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima, the three Tohoku prefectures directly impacted by the disasters, prices for building plots, materials and construction work have soared. For the last three years, districts located on high ground in the tsunami zone have occupied the top five places in the whole of Japan in rankings of land-price increases. Shirasagidai, a district of Ishinomaki, has been number one for three years in a row, with a cumulative increase of 129 per cent.2 These days the reconstruction drive is in competition with demand from Tokyo to prepare infrastructure for the 2020 Olympic Games. One result of this has been a serious labour shortage – another factor holding up reconstruction.

The most significant series of events for most communities surrounds the creation of a ‘recovery plan’ (fukkō-an), a rebuilding plan for each community, required by the state and approved by each prefecture. But with many coastal zones declared too dangerous for habitation, these plans have faced the intractable challenge offinding land that is both large enough to allow the relocation of whole communities, and close enough to the original site to preserve social and economic systems.

The recovery plans were supposed to give communities a say in relocation decisions, but there was internal division among residents and pressure from different business interests that conflicted with community desires. Eventually local residents often had plans foisted upon them that were so complicated and vague that even civil engineers had trouble understanding them. What was supposed to be community building has as often as not been a source of strife and conflict. Even if there were available housing, ← x | xi → the money that residents could patch together from compensation payments, insurance and savings was often not enough to allow them to buy back into their own community. The net result has usually been smaller, poorly constructed and more expensive housing and the break-up of neighbourhoods and communities.

The challenge of agreeing on and executing recovery plans has seriously held up the disbursement of government reconstruction funding. As of November 2014, only 2,700 housing units had been completed in the tsunami zone, less than 10 per cent of the 29,000 units planned. The government had already transferred 5.5 trillion yen in reconstruction funds to local authorities in Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures, but some 60 per cent of that money remains unspent in local bank deposits.3

A few families have already been able to move into newly built accommodation, some into houses, but many more into apartment blocks, a cheaper option for rapid construction. Sadly, however, many of these units remain empty, reflecting poor planning in cases where housing was built without first obtaining solid commitments from households to move in. Families used to living in large rural homesteads are reluctant to move into small apartments, while many single or elderly people prefer to stay on in the temporary housing complexes. Though rudimentary, the temporary housing units are rent-free, and a kind of alternative community life has developed in the complexes. That community life will be destroyed when people move to the widely scattered ‘recovery housing’ units. Moreover, most of the newly constructed apartment blocks are quite far away from where people have lived before and often lack infrastructure, such as accessible shops and bus services.

Thus, the net result of the rehousing programme includes a tragic irony – that people who were driven from their furusato, or home town, and have improvised a new community in the temporary housing complexes, may find themselves expelled from home, or a place that feels like home, for a second time when the housing complexes are finally closed down. ← xi | xii → At present, however, most of the complexes are being kept open, their period of use extended from the initially planned two years to three, then four years.

The fishing industry of the Sanriku coast shows a mixed picture. The disasters have accelerated some trends. For instance, a large number offishermen have retired early, given that it would have been impossible for them to pay back a huge loan to buy a new boat to replace one destroyed in the tsunami. However, fishing activities in Iwate and Miyagi prefectures have recovered to a large extent, and 7 per cent of the fishers operating there are newcomers (a phenomenon that could also be observed after the great tsunami of 1896 and 1933).4 After three years of cultivating, farmed oysters and clams can now be harvested again. The biggest challenge is to keep one’s clients, as they naturally switched to other producers during the years when aqua farmers had to invest but could not harvest.

As a result of high levels of radiation, there is no fishing being done in the area around the Fukushima nuclear power plant except for experimental purposes, but even further up the coast, fishers are very aware of the problem. To avoid fūhyō higai, or ‘damaging rumours’ that depress sales, they subject their harvest to strict radiation testing to demonstrate that they are safe to eat. Not everyone is convinced. In September 2013 Korea prohibited the import of hoya (sea squirt, used in the production of kimchi) from the Sanriku coast. For hoya farmers this means that they have lost the majority of their clients, and they are now trying to promote hoya as a regional specialty. Other strategies have included direct sales, branding of products to associate them with the locality rather than with the disaster zone, and the seeking out of supporters who will become shareholders in cooperative sales ventures.

A highly controversial issue in communities along the Sanriku coastline is the construction and repair of seawalls. Some 400 km of seawalls are planned, at tremendous expense to the taxpayer. Often these big-ticket construction projects are decided at the prefectural level and local communities have often opposed them, for many reasons: they impede fishing operations, disrupt the local ecology, create new dangers by reducing ← xii | xiii → the visibility of the sea and spoil the view, thereby discouraging tourists. They also prevent water from running back to the sea after a tsunami, instead pooling it behind the walls and thereby worsening damage and hindering post-tsunami clean-up. Furthermore, the future expense of maintaining the walls will be prohibitive for coastal communities faced with a dwindling and ageing population.

Critics also question the effectiveness of seawalls as safety barriers, since some communities with high walls suffered high mortality rates in the 2011 tsunami after being lulled into a false sense of security. Strong community ties leading to well-organized evacuations appear to have been more effective at reducing tsunami damage. Many of the worst affected communities have been forced to relocate to higher ground anyway, meaning that there will be little or no housing for the seawall to protect.

In October 2014, the prefectural government of Miyagi gave in to sustained opposition and agreed to cancel plans for new seawalls in three communities in Ishinomaki that had been vehemently opposed to them: Yoriiso, Fukkiura and the island of Aji. The local movements against seawall construction have been less noticeable to outsiders than the nationwide movement against nuclear power plants, but their occasional successes in delaying or cancelling seawall construction show that grassroots movements can sometimes influence the major centers of political power.

The health and welfare of people living in remote rural districts affected by the disasters is another serious problem. There are few incentives for doctors to live in remote areas and the disasters have further depressed the appeal of work in Tohoku. In Brigitte Steger’s research site of Yamada (Iwate prefecture), for instance, there is no gynaecologist or paediatrician in a town of about 17,000 inhabitants. One private clinic re-opened in the town centre in the summer of 2014, but the prefectural hospital in Yamada was destroyed by the tsunami and replaced by a prefabricated ‘temporary day clinic’. By the summer of 2014 there was only one physician employed their full time: Hiraizumi Sen. Hiraizumi trained as a surgeon and studied at Harvard, but he now works as a general practitioner, especially in geriatric and palliative care.

He sees patients at the clinic all morning. In the afternoon, he and two nurses make home visits to take temperatures, give drip-feed infusions, prescribe medicine and change diapers of elderly bed-ridden people. On ← xiii | xiv → weekends, the clinic is closed, and Hiraizumi goes on home visits alone. With his self-sacrificing commitment to home visiting, he ensures that bedridden patients can stay with their families in a familiar environment and at low cost. He also saves lives, especially in emergencies. Yet there are not many physicians like him, and home care in general is not well developed. For many families, driving their elderly relatives to a far-away hospital is the only way to get care.

Volunteers continue to go to the disaster zone, though the numbers have dwindled as the immediate physical needs of the people there have diminished with time. They still help farmers and fishers with tasks such as preparing the ground, transplanting crops, cleaning tools, seeding seaweed, etc. In the Shobutahama neighbourhood of Shichigahama, which was 80 per cent destroyed by the tsunami (see Johannes Wilhelm and Alyne Delaney in this volume), volunteers carry the mikoshi (portable shrine) in a local festival; even by the summer of 2014, there were not enough young local men able to perform this task. Nationally, there is a continued rhetoric of service and many universities are setting up programmes of ‘service learning’ to institutionalize this sentiment and experience.

However, much of the assistance now required – such as for legal advice on making claims for compensation or psychological help in the form of ‘kokoro no kea’ (care of the heart) – requires longer term commitments and more training than even locally based volunteers groups can provide. Much of the work now shifts back to the state.

The Fukushima nuclear disaster continues to cast a long shadow over Japanese society. As of November 2014, all fifty of Japan’s nuclear reactors were shut down. Two reactors, at the Ōi nuclear power plant in Fukui prefecture, were restarted in July 2012, despite formal objections from both the city and prefecture of Osaka, the biggest consumer of electricity from Ōi. In September 2013 the two reactors were shut down for regular inspections and since then there has been no nuclear power generated in Japan. Many of Japan’s nuclear reactors are located on or close to geological fault lines, and there is intense argument as to whether those fault lines are active or not. Moreover, all of the reactors are located close to the sea and therefore exposed to some degree of risk from future tsunamis. The Abe government has attempted to keep nuclear power as part of Japan’s energy mix by setting new safety standards that it claims are the toughest ← xiv | xv → in the world to be enforced by a specially created body called the Nuclear Regulation Authority.

By the summer of 2014, the NRA had received applications to restart eighteen reactors at eleven power plants, and in September 2014 it issued its first ever approval – for two reactors at the Sendai plant in Satsumasendai, Kagoshima prefecture, southern Kyushu. At the time of writing it seems possible that the two reactors at Sendai could be reactivated early in 2015, ending a period of well over a year in which Japan generated no electricity from nuclear reactors.

In Fukushima the economy continues to struggle with the challenge of persuading consumers that agricultural produce from the prefecture is safe. According to the latest survey conducted by the Consumer Affairs Agency, Government of Japan, in August 2014, 19.6 per cent of respondents said they were hesitant to purchase produce from Fukushima, with a further 28.4 per cent naming wider areas of Tohoku from which they were hesitant to buy. In the same survey, 25.9 per cent of people did not know that food was being tested for radioactivity to ensure safety.5

Meanwhile, anti-nuclear demonstrations have continued. Though the scale and frequency of demonstrations has declined, there have been interesting developments in the range of people involved and the ways in which the anti-nuclear movement works. In the three decades before 3.11, most political activity had been organized by labour unions in which participation was mainly by men employed in regular jobs from urban locations. This has changed in a number of ways. First, young people who took the initiative in the early days of the disaster (see Tuukka Toivonen in this volume) have often been leaders in organizing and networking of anti-nuclear protests. Organizations like the Metropolitan Coalition Against Nukes and the Twitter-based TwitNoNukes have mobilized a new generation of socially disaffected, previously politically unengaged, and technologically sophisticated young people. The events they stage are as likely to reference European precarity events as post-war labour demonstrations.

← xv | xvi → Second, patterns of geography and gender have been upset. While many of the most visual protests are in Tokyo, the rate of participation is probably higher among people from Tohoku, and especially Fukushima. People confronted with the most immediate threats to health have found support and information that has led to local activism. Sometimes organized through NPOs, agricultural producers or consumer groups, at other times through less formal, even neighborhood groups, their alliances cut across age and occupation in ways that make new spaces for residents to question governmental prioritization of economic recovery over concerns for safe food, land and water.

These groups are often led by women: young mothers and older environmental activists, as Morioka Rika observes in this volume.6 While younger generations tend to recoil from the stigma offist-raging radical activism, some have formed a style of ‘gentle’ protest, aspiring to a lifestyle different from those of their postwar generation parents devoted to Japan Inc. For them, nuclear power plants symbolize the wrongness of economy-centered policies. The disaster in 2011 provided common ground to unite generations of protesters. Sometimes the geographical gaps between Tokyo and Tohoku are bridged, too, as in the case of Fukushima Women Against Nukes, a group that has garnered international media attention through their presence at Tokyo demonstrations, while keeping local ties with Fukushima communities and families.

In Fukushima, about 130,000 people remain displaced by the nuclear disaster, and for many of them there is no prospect of returning to their communities for decades to come, if ever. The prolonged operations of stabilizing the crippled reactors at the Fukushima No.1 plant, staunching the emission of radiation into the local environment and decontaminating the surrounding area proceed at a snail’s pace. An interim waste storage site has now been agreed at a site straddling the two townships of Futaba and Ōkuma, where the No.1 nuclear power plant itself is located. These townships will not be inhabitable for decades, so there is a certain ← xvi | xvii → inevitability about the decision to create the contaminated waste storage site there. Compensation payments to the two townships will total some 300 billion yen.

The deal over the interim dump site included a legal guarantee that the waste materials contained at the facility would be moved outside the prefecture within thirty years. Still, the deal offers a temporary answer to the question of where to put some 20 million cubic metres of radioactive waste, currently stored in piles of bags at some 54,000 locations around Fukushima prefecture.7

The issue of compensation for the victims of the nuclear disaster is also ongoing. For people in the worst affected areas, total compensation to date for the psychological damage of forced relocation has reached about 15 million yen per person, or 75 million yen for a household of five. Many households now have enough money to buy a house elsewhere, and a growing number of them have done just that. For example, by autumn 2014, roughly 300 out of the 1,800 households in Iitate village had bought houses, including 30 of the 71 households in Nagadoro hamlet (see Tom Gill in this volume). With every house bought, the number of villagers likely to return after decontamination is reduced; as a result, at this point there seems to be no chance that village life will return to anything like what it was before the disaster. What is true of Iitate is even truer for the communities closer to the nuclear power plant, such as Namie, Tomioka and, of course, Futaba and Ōkuma. These communities have almost certainly been dispersed permanently.

Details

- Pages

- XXII, 318

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781906165512

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035306972

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035399899

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035399905

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0353-0697-2

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2013 (October)

- Keywords

- life relationships anxiety discrimination fishing industry Anxiety Survival Tsunami Disaster Local community

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG