Partial Visions

Feminism and Utopianism in the 1970s

Summary

This book explores the transformative potential of feminist visions of change, even as it sees their ideological blind spots. It does more than simply look back to the 1970s. Instead, it looks ahead, anticipating some of the shifts and changes of feminist thought in the following decades: its transnational scope, its critique of identity politics and the gendered politics of sexuality, and its embrace of affect as an analytical category. The author argues that the radical utopianism of second wave feminisms has not lost its urgency. The transformations they envisioned are still our challenge, as the vital work of social change remains undone.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Figures

- Introduction to the Classics Edition

- Introduction to the First Edition (1991)

- Chapter One: “Wild Wishes …”: Women and the History of Utopia

- Chapter Two: Utopia and/as Ideology: Feminist Utopias in Nineteenth-Century America

- Chapter Three: Rewriting the Future: The Utopian Impulse in 1970s’ Feminism

- Chapter Four: Worlds Apart: Utopian Visions and Separate Spheres’ Feminism

- Chapter Five: The End(s) of Struggle: The Dream of Utopia and the Call to Action

- Chapter Six: Writing Toward the Not-Yet: Utopia as Process

- Conclusion to the First Edition (1991)

- Conclusion to the Classics Edition: Feminism and Utopianism, Then and Now – A Roundtable Dialogue

- Roundtable Participants

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series Index

My acknowledgements for the initial edition of Partial Visions were limited to the group of people – my academic mentors, closest friends and immediate family – who first helped me find my way to this project and sustained me, intellectually and emotionally, along the way. My mentors at the University of Wisconsin-Madison read it in its first iteration in the form of my doctoral work. Fannie LeMoine encouraged me to “pursue the Christine de Pizan idea.” David Bathrick always urged me to recognize the political dimensions of what we call “cultural.” Evelyn Torton Beck’s question, “what about the women” opened a world that has been my home ever since. Susan Sniader Lanser was my most “supportive and exacting critic, constant friend, the embodiment of my ideal reader,” as I put it in my first acknowledgments, and decades later, she is still all of that and more. My husband, Dewitt Whitaker, was there for me through the thick and thin and ups and downs of writing. It is a rare constancy for which I will always be grateful. Apart from these people whom I named specifically, there were the many women (and a few men) – friends, students, and colleagues, here and abroad – whose “passionate politics” (Bunch 1987) and love of words and literature helped me understand the power of language to create worlds – as well as destroy them. And there were those helped produce the book: Karen Carroll and Linda Morgan at the National Humanities Center in North Carolina, who typed the manuscript, and my editor at Routledge, Janice Price, who was there from the moment she took on the manuscript to the champagne toast when the book was finally done.

I concluded my initial acknowledgments by reflecting on the invariable conflict those of us face who live as parents and work as scholars. “It has always seemed strange to me to thank one’s children,” I wrote, “especially when they are still very young, for ‘giving’ what we essentially simply take, namely the time and attention we give to our work. It is my hope that my children, Bettina and Nicolas Bammer-Whitaker, will learn that the time ← xi | xii → that we, their parents, take is not stolen from them, but the necessary means with which to fashion something of worth. Perhaps some day it will have meaning for them; perhaps it will not. Thus, I do not thank, but at this point, merely remember them. For surely my children, born during the time of my work on this project, are the most concrete embodiments of one of my most utopian impulses.”

As I prepare to launch Partial Visions for a second round, now endowed with the honorific of a “classic,” I am again aware – perhaps more than I was the first time around – of the network of support on which scholarly work depends. We build on scholarship that went before; we are part of intellectual communities that sustain and enrich our knowledge, our thinking, our writing. One such community is represented in the roundtable that concludes this book: scholars whose work explores the relationship between feminist and utopian thinking and engages the question of what a utopian feminism could be. They include Evelyn Beck, Fran Bartkowski and Sara Lennox, with whom I have been discussing what a feminist future might be for over three decades; Ruth Levitas and Lucy Sargisson, whose work on feminist utopianism and the radical potential of utopian thought is a foundation on which I build; Ildney Cavalcanti, Raffaella Baccolini and Jeanne Cortiel, who showed me what the dark side of utopia can reveal; Kathi Weeks, Naama Nagar and Tahereh Aghdasifar, who put utopian thinking to the test in the arena of real-world struggles. In our work together, all of them modelled a commitment to collaboration that was a utopian gesture in itself.

Other intellectual communities have sustained, supported – and at crucial times challenged – my thinking as I wrote this book. At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Jost Hermand and Klaus Berghahn have been a sounding board for debates about utopia – its revolutionary potential and its reactionary risk – ever since I was a graduate student in Madison, and their colleague, Eric Olin Wright, carries the debate forward with his work on what he calls “real utopias.” Across the ocean – in the city of Limerick in the Mid-West region of Ireland – is a community of scholars and activist thinkers whose work I have followed and admired for the past decade: the community affiliated with the Ralahine Centre for Utopian Studies. Since its founding in 2003, the Centre has been a fulcrum of scholarly research ← xii | xiii → and public debate about the futures we want, the futures we need and the futures we have to start building. We can’t afford to cede reality to the realists, this work insist – we need the dreamers to offer counter-realities.

None have been more critical to the fostering of this inquiry than the Centre’s founder and co-director, Tom Moylan. From our first conversations about Ernst Bloch when we were both students at the University of Wisconsin (Tom in Milwaukee and I in Madison) through his ground-breaking work on “science fiction and the utopian imagination” (Moylan 1986) to his creation of the Ralahine Centre, Tom has modeled the radical idea that utopia isn’t a dream to be deferred to a distant future. For Tom, utopia begins here and now, with us: how we live, how we treat one another, and what we do with the means available.

The students in my “Good Worlds, Bad Worlds” seminars at Emory University were willing to entertain this radical idea. They engaged, challenged, shocked and moved me with the honesty of their hopes and fears. At times, they turned my very assumption upside-down. Ian McCall’s picture of a devil was one such moment. Asked to bring an image of something utopian, they brought a set of mostly Hallmark card clichés: pastoral landscapes, lovers at sunset, kittens in baskets and big-eyed fawns. Ian, who was starting college after tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, brought a different picture: his was monster with a devil face. “In my utopia,” he explained to his classmates, “we would be told and learn to face the truth. And the truth isn’t always pretty. It includes violence and suffering and evil”.

But a book is more than thinking and writing. Materials have to be assembled and the book has to be produced. Toward this end, the work of many people was indispensable. Marie Hansen and the staff of the Interlibrary Loan office at Emory University managed to find everything in every language I was looking for. Kim Collins tracked down the German newspaper article from 1978 that I was missing. Lolitha Terry, graduate program administrator in my department, the Graduate Institute of Liberal Arts, faxed and mailed me materials when I was away and didn’t have access to a university library. Colleagues and students provided references and loaned me texts that I didn’t have. One of our graduate students, Christopher Lirette, found the passage in Foucault I was looking for and sent me the French original. Staff in archives, libraries and research centers ← xiii | xiv → in the United States, England, France and Germany sent me information and materials and gave me access to their collections. Helke Schlaeger from the German Frauenoffensive press tracked down the original source for the image of Ishtar that I used in chapter four (figure 5). Dagmar Nöldge, the archivist at the Frauenforschungs-, -bildungs- und –informationszentrum (FFBIZ) [Center for Research, Training and Information about Women] in Berlin, not only brought trays of posters, buttons, and women’s movement memorabilia for me to look through, but let me take my shoes of and stand on the table to photograph the buttons without reflections from the overhead lights. Publishers, booksellers, and editors shared experiences and information and artists gave permission to reproduce their work. Gabriele Goettle, whose collage I used in chapter five (figure 6), shared her perspective on some of the divisive debates within the West German women’s movement. The Guerrilla Girls gave me permission to use their image (figure 8) and said they would “love to be included” in my feminism and utopianism book.

Heather Kelley did the equivalent of spinning straw into gold when she changed pdf files of the book into Word files. It tested the limits of our combined technological skill (not to mention patience) and I am grateful for her perseverance, attention to detail, and commitment to not give up, but complete the job.

I am grateful to the editors of the Ralahine Utopian Studies book series – Raffaella Baccolini, Tom Moylan and Joachim Fischer – for inviting me to submit Partial Visions for reissue in their “classics” series and helping me ready it for publication. Christabel Scaife, the commissioning editor at Peter Lang, is the editor every author dreams of: efficient, encouraging, practical and generous.

Richard Steven Street helped ground my thinking and make my writing clearer. “Do good work,” he would say when I headed off to my study. I think of these words as directions toward the kind of world I would like to help make.

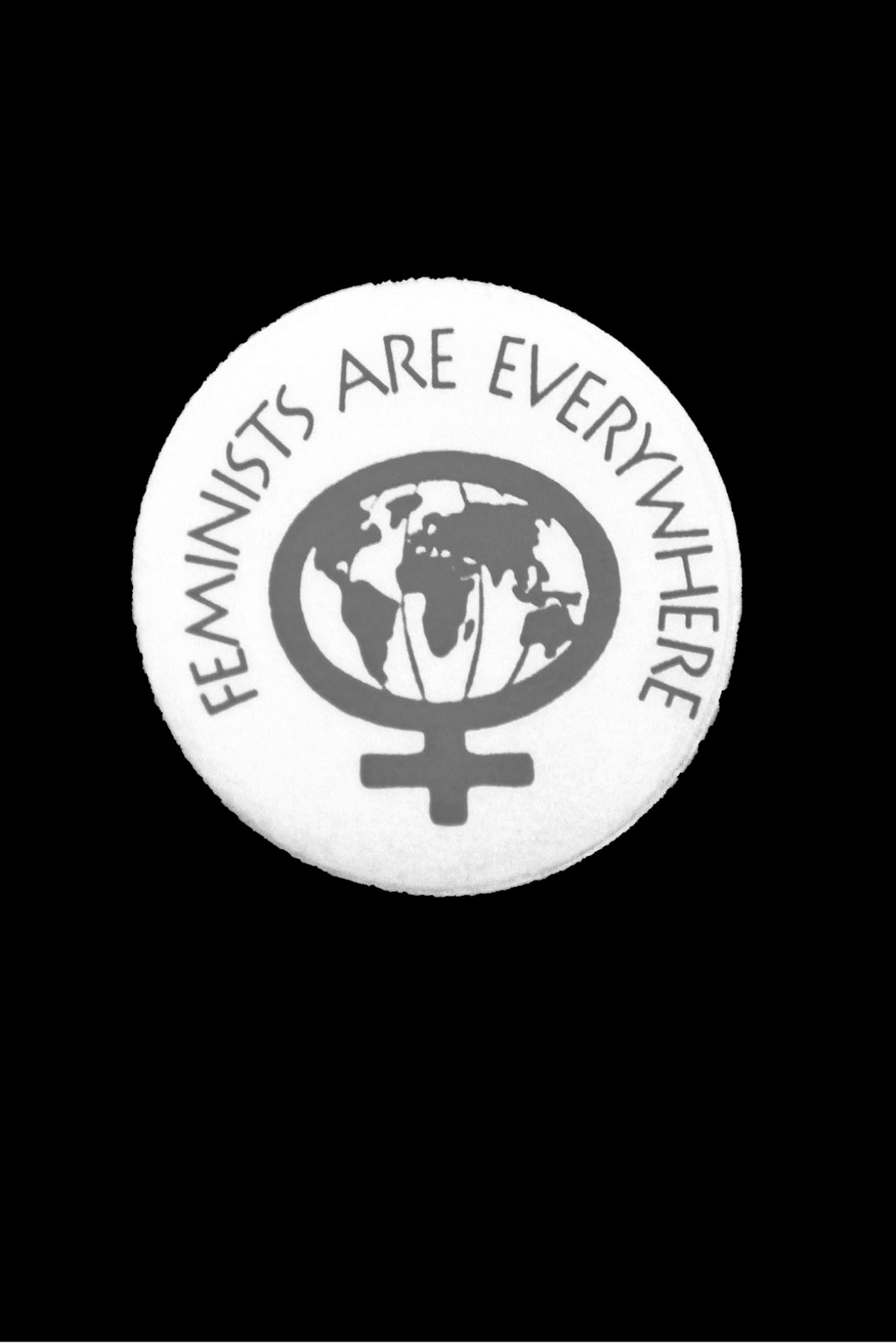

| Figure 1. | Pinback button. United States, 1970s. |

| Figure 2. | Entry banner to The Dinner Party. Judy Chicago, 1974–9. |

| Figure 3. | International Women’s Day poster. Karl Maria Stadler design, 1914. |

| Figure 4. | International Women’s Year poster. Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective, 1975. |

| Figure 5. | Ishtar. Sumerian-Akkadian culture, c. 2000 BCE. |

| Figure 6. | Collage. Gabriele Goettle, 1976. |

| Figure 7. | Pinback button. West Germany, 1970s. |

| Figure 8. | Fist. Guerrilla Girls, c. 1985. ← xv | xvi → |

Figure 1. Pinback button. United States, 1970s.

(overleaf ) This pinback button is typical of the small, metal buttons (c. 2 ¼˝) that were mass-produced and widely distributed within the context of the women’s movements of the 1970s. In this, as in most cases, the name of the artist/designer, as well as the precise date and place of origin, of a particular design, cannot be identified. Even when collected, they were not regarded as objets d’art. They were objects used for political purposes: handed out freely and worn or displayed strategically. This button can be traced to the American women’s movement, sometime in the 1970s. The background is white; lettering and design are burgundy.

Source: FFBIZ- [Frauenforschungs-, -bildungs- und Informationszentrum] Archiv, 1 Rep. 2 USA 20 (397), FEMINISTS ARE EVERYWHERE. Used by permission. Photograph by author.

Introduction to the Classics Edition

“The Unfinished The Unbegun The Possible”1: Partial Visions, A Generation Later

Think about the 1970s and you might draw a blank. The 1960s – that’s when things were happening. But the seventies …? That’s when “I’m OK, you’re OK” replaced the struggle for social justice, and traditional values, including established gender roles,2 returned. It was the “Me Decade,” as the literary journalist Tom Wolfe defined it (Wolfe 1976),3 a time of mood rings and smiley faces, the period that pivoted the activist sixties, when a vocal minority wanted to change the world, to the conservative eighties, when a silent majority wanted to keep the world the way it was. When I asked a historian friend, “What did the 1970s stand for, what of significance did this decade bring,” he thought about it for a moment, puzzled. “Kind of a lost decade,” he finally shrugged.

This book tells a different story about the 1970s: a story, not of loss, but discovery, of wild dreams and bold visions for change. It is a story of voices, histories and memories that had seemed lost, but were retrieved and charged with new energies. It is a story of women who traveled through time and space, across centuries and cultures; women who could fly, and change shape and speak the language of plants and animals; women who built cities and created worlds designed for women; who shaped language and measured time to the rhythm of women’s bodies. It is a story of a time when women tried to imagine how the world could – and should – be changed for the good of women and what such a change might mean for the good of all. Their vision was radical and it was born of a passionate sense of urgency. The need was evident and the time was now. No one expressed ← xix | xx → this need more powerfully than the American poet, lesbian, and feminist thinker, Adrienne Rich:

We need to imagine a world in which every woman is the presiding genius of her own body. In such a world women will truly create new life, bringing forth […] the visions, and the thinking, necessary to sustain, console, and alter human existence […] Sexuality, politics, intelligence, power, motherhood, work, community, intimacy will develop new meaning; thinking itself will be transformed. (Rich 1976: 292; emphasis added)

This sense of urgency, of radical changes that had suddenly become not just imaginable, but thinkable, even possible in the course of time, marked the 1970s that I remember. Of course, women weren’t literally flying, communing with plants, or building whole cities for women only. But by imagining what it would mean to do so, they were figuratively doing just that. This is the story of the 1970s that I wanted to tell: a story of radical imaginings and their power to change things. Partial Visions was my way to tell it.

My perspective was in every way partial. I was invested in the issues I was writing about. I was engaged in the politics of feminist culture. I didn’t want to write about literature in the abstract as an academic or about the seventies like a social scientist. Nor did I want to talk about feminism or utopianism on some meta-theoretical level. I wanted to write about a body of creative work that excited me because it was bold and fresh and different from anything I had ever before read. It was a body of work produced by women over the course of the 1970s who didn’t distinguish between the art of writing, critical thinking, and political engagement – they were writers, theorists, and activists, all at once. It was work that combined feminist politics, utopian thought, and a literary creativity that thrilled me. It was work that changed me. It changed how I thought and what I thought about. It changed how and what I read. And eventually it changed how I wrote and what I wrote about.

Revisiting my book now, from the distance of a generation, I am struck by a certain incompleteness. The book ends before the story as such is over. I point in directions, identify impulses and raise questions that I leave open. There are no grand conclusions and few definitive answers. I have reframed ← xx | xxi → it with a new introduction and a roundtable discussion that forms a new conclusion, but I have left the book essentially as I wrote it then.

Far from a failing, this incompleteness is integral to the story I set out to tell. For it is a story of what we see when we change the angle of our gaze from the arc of history as it crests in defining moments to perceive a movement in the first stirrings of what may not even yet be conscious as a movement, much less have a name. It didn’t feel like it at the time (my attention was distracted by the scholarly conventions of what it meant to write a book in my field), but as I look back, I think I was trying to capture this very sense of a movement emerging, the inchoate and messy beginning of something that, only in retrospect, can be seen as “history.”

It’s not that there hadn’t already been the occasional big banner moment when the force of a movement had made itself known (and over time such moments would increase to acquire the density of a history we could name). But as I experienced it in the early seventies, what we were calling a movement still mostly spoke in what the writer, Doris Lessing, called “a small personal voice” most commonly heard in the private conversations among women about their lives, their troubles, their longings (Lessing 1974). To describe a movement in this early phase was like describing a river at its point of origin, when neither its sources nor its trajectory are yet clear.

The thrill and the challenge of what I was trying to write back then were inherent in this attempt to tell a story that was still unfolding. Neither the beginning nor the ending were yet clear, because we – and I was part of that “we” – were still in the midst of it, figuring things out.

In its review of the particular blend of feminist and utopian thought that emerged from the women’s movements of the 1970s Partial Visions is an integral part of the cultural history of a social movement. Even at the time, in the middle of events whose outcome was still undecided, we knew that we were making history, setting things in motion for a future we could not yet see. And in light of this future that we were in the process of shaping, we also knew that we were responsible for remembering what we had started so that we – or those who came after us – could pick up where we left off.

I wrote Partial Visions in the spirit of such remembering. It is being reissued with much the same intent. It looks back, but not with nostalgia. It is not an elegy for a movement’s past. It is a work of recovery, an ← xxi | xxii → archeology of recent cultural memory that aims to retrieve and preserve what I believe is one of the most generative dimensions of second wave feminism: its utopian impulse. This impulse should not be forgotten in the annals of a “lost decade.”

I hope that the reissued book will be read as more than an archive of cultural memory. I hope that reading it will become an act of remembering in its own right. For remembering is active. It does things. It has effects. It can reanimate past dreams and commitments and remind us that what we initiated – the movements for change in the name of “women” – is not yet finished. “[W]e stream into the unfinished the unbegun the possible,” Adrienne Rich wrote in the mid-seventies (Rich 1978: 5). Much has begun, much remains unfinished. As for what remains possible, we can only know what that might be from where we are at a given moment.

For me, it began in Memphis in April 1974. People were assembling for the annual march commemorating the assassination of Martin Luther King and his vision of social and economic justice. We were marching for job protection and a livable wage for working people, rights and dignity for the poor, equality and respect for people of color. Volunteers were distributing black armbands emblazoned with the words, “I Am a Man,” the slogan of the sanitation workers’ strike in 1968 that had won the strikers union recognition and wage increases and cost Martin Luther King his life. Someone handed me an armband, but as I reached for it, I suddenly wasn’t sure I wanted to wear something that said, “I Am a Man.” I realized that it wasn’t meant literally. I understood the symbolic meaning of words. I knew what this slogan had meant to the workers who had gone on strike in 1968 and what it meant to the Black men who had gathered for this march in downtown Memphis. It meant something different to them than to me, a white woman. I was distressed by my own confusion and torn about what to do, but the distributors of the armbands didn’t have time for “a hundred indecisions.” There wasn’t time “to prepare a face to meet the faces.”4 Did I want to join the march or didn’t I? I took the armband, slipped it on, and took my place in the line. But something fundamental had shifted in my sense of who I was in relation to the world around me, and I needed to figure out what this shift meant. ← xxii | xxiii →

Details

- Pages

- LI, 365

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034308977

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035307481

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035399080

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035399097

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0353-0748-1

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (December)

- Keywords

- second wave women race utopia gender

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2015. LI, 365 pp., 8 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG